Out of this world: The rise and fall of Planet Sci-fi’s ‘competent man’

Today’s science fiction literature is a diverse landscape, says David Barnett, but it wasn’t always like that. A new book looks at the origins of the genre’s Golden Age… and the women who were airbrushed from history

In August this year, the writer NK Jemisin was called to the stage at the World Science Fiction Convention in San Jose to collect her third consecutive Hugo Award for the best novel of the year.

Three wins on the trot for one of the most venerable and hotly contested awards in science fiction is remarkable enough. The fact that Jemisin is a black woman made her winning streak all the more historic.

It’s probably something that shouldn’t even need to be mentioned; after all, the contemporary science fiction scene is more diverse than it has ever been in its history, and women writers and people of colour are the norm, not the exception.

This week the reader review site Goodreads launched its annual Goodreads Choice Awards. There are 15 titles in the first round in the science fiction category; seven are written by women. Only four are written by white men.

So why is it worth talking about at all? Because the origins of the contemporary science fiction field were anything but diverse, as outlined in a new book, Astounding, by Alec Nevala-Lee.

Astounding takes a certain focus in the look at the history of science fiction literature, looking at the start of what is commonly called the Golden Age, which is generally accepted to have run from about 1939 to 1950.

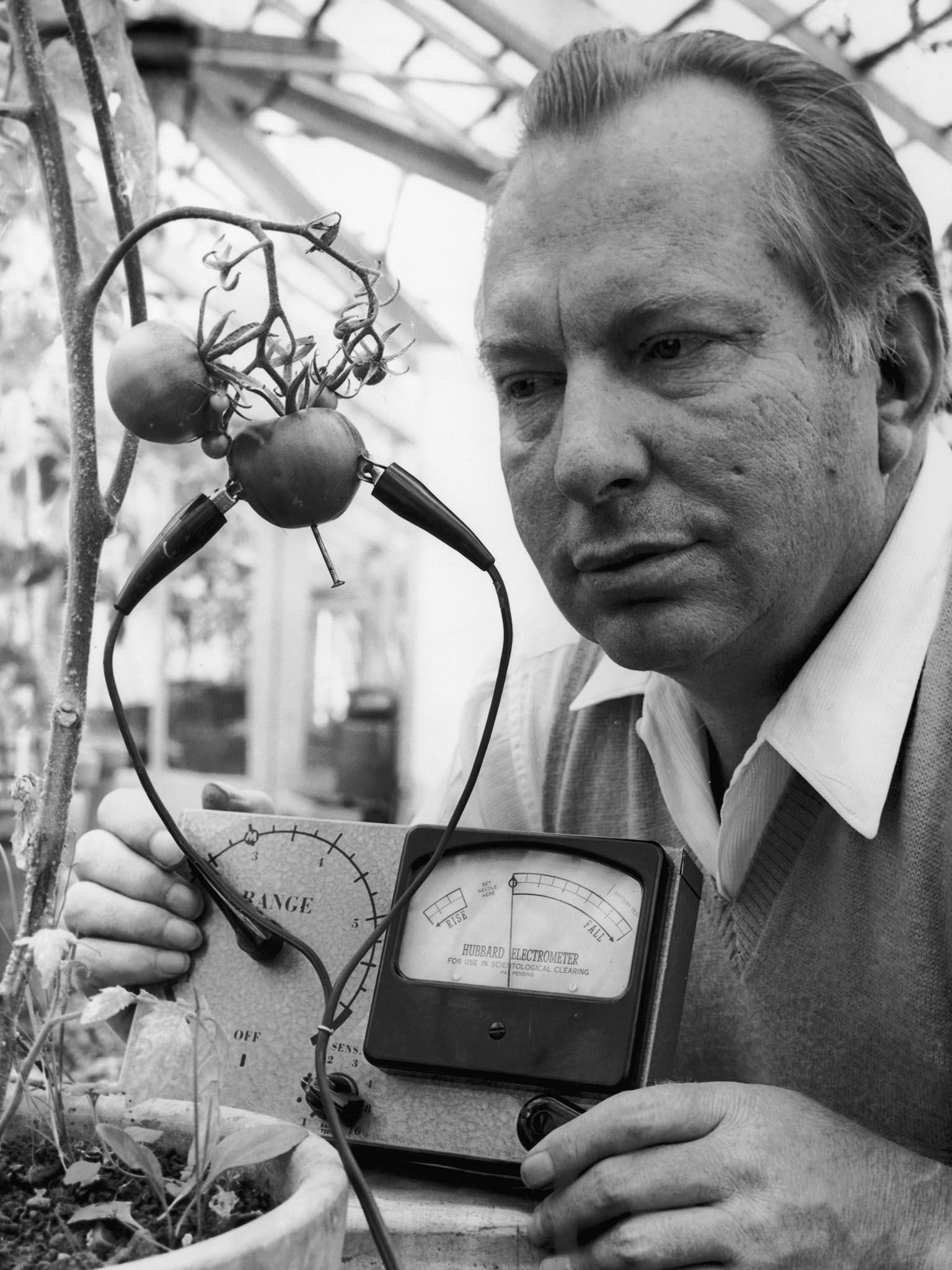

Even if you’re not particularly au fait with the world of science fiction writing, some of the names from that era will certainly be recognisable; Isaac Asimov, who wrote a multitude of novels and short stories including the sequence which was loosely adapted into the movie I, Robot, starring Will Smith. Robert A Heinlein, author of Stranger in a Strange Land, Have Spacesuit – Will Travel, and Starship Troopers (among a plethora more), the latter of which also got the big screen treatment in 1997. L Ron Hubbard, who later became much more notorious as the founder of the Church of Scientology but, back in the 1930s, was one of the triumvirate of young writers, along with Asimov and Heinlein, who form the narrative backbone of Nevala-Lee’s history.

But the book is also – and primarily – the story of John W Campbell, who won’t have the same recognition factor, but who is considered one of the most important figures in the history of science fiction.

Campbell was born in 1910 in Newark, New Jersey, and had a prolific writing career until he was appointed editor of Astounding magazine in 1938. He brought on and encouraged Asimov, Heinlein and Hubbard – three very different and often conflicting characters – and ushered in the Golden Age.

When we think of the Golden Age we think of the classic science fiction tropes. Optimistic futurism at a time when the real world was chugging towards global warfare. Sleek rockets and square-jawed heroes, damsels in distress menaced by slimy, tentacled aliens.

It’s an image of science fiction that is largely absent in the form today, but back in the late 1930s, perhaps because the world was rapidly becoming a rather dreadful place, this unique brand of escapism began to gain traction.

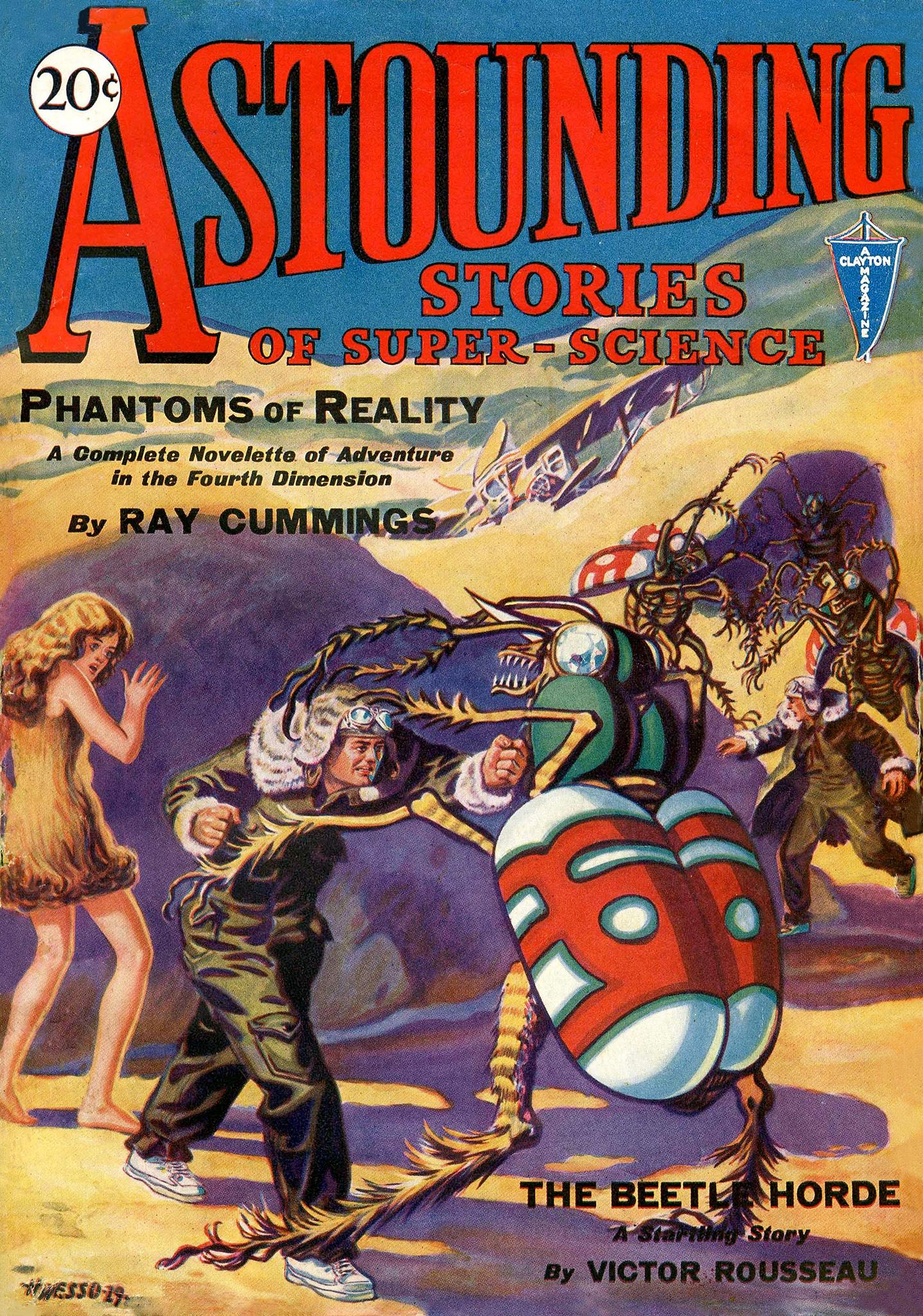

If you wanted your science fiction in the Golden Age, it came in the written form. Magazines such as ‘Astounding’ proliferated and serialised novels or published short fiction

It was still, from the mainstream point of view, a relatively niche genre. Today, science fiction is ubiquitous. TV and streaming services such as Netflix are full of it – Stranger Things, The Handmaid’s Tale, Black Mirror. Doctor Who is enjoying one of its most notable periods ever. At the multiplexes, people who would never consider themselves science fiction fans routinely push films such as the Star Wars franchise, Ready Player One, the Marvel movies, to the top of the box office lists.

But back in the Golden Age, sci-fi was largely absent at the movie theatres, save for the chapter serials featuring Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, and it wasn’t until the 1950s that the schlocky drive-in alien invasion craze started, fuelled by post-war fears about communism and the enemy within. TV didn’t really catch up until the 1960s, with Star Trek, The Outer Limits, Land of the Giants.

So if you wanted your science fiction in the Golden Age, it came in the written form. Magazines such as Astounding proliferated and serialised novels or published short fiction. This is where the genre was really born, and something else was minted as well; the image, which stood for a very long time, of science fiction as something almost exclusively white and male.

Nevala-Lee notes that the science fiction that Campbell decided to shape was all about “the competent man” – the hero who would save the world, the galaxy, the universe. Nevala-Lee writes that Campbell’s term “points to the way in which science fiction encourages certain assumptions. Editors like Campbell tended to favour writers who looked like them, and from the start, fandom was overwhelmingly male. Women were often regarded with suspicion, and even when they were welcomed, they could still be treated poorly.”

Though Campbell occupies a special place in science fiction history, he held some pretty abhorrent views. His omission of black characters, for example, wasn’t just something to put down to him being “a man of his time”, or ignorance; it was a wilful decision.

Nevala-Lee quotes Campbell as saying, “Think about it a bit, and you’ll realise why there is so little mention of blacks in science fiction; we see no reason to go saying ‘Lookee lookee lookee! We’re using blacks in our stories! See the Black Man! See him in a space ship”. Nevala-Lee observes: “The implication was that protagonists should be white males by default – a stance that he might not even have seen as problematic.”

Campbell was also stoutly anti-feminist, saying that women who demanded equal rights also refused to give up what he considered their “girlish special privileges”. He once declared, “No woman has ever attained first-rank competence in literature in any Indo-European language.”

It’s not that there weren’t science fiction writers who were people of colour or women (or both) back in the Golden Age… it’s just that they didn’t get a look in. Samuel R Delany, now 76, is considered one of the most important writers in the genre ever. He’s also African-American, and gay (Campbell had a lot to say about homosexuality, as well, and none of it good). While once grudgingly admitting of Delany “this guy can write and has a lot of brilliant ideas” he constantly rejected Delany’s submissions, and turned down the novel Nova – which would go on to be a rightly-regarded classic. Delany recalled that Campbell “didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character”.

Campbell did publish several women writers, though later on in his career, including Anne McCaffrey, Kate Wilhelm and Alice Sheldon, whose first story “The Birth of a Salesman” appeared in one of Campbell’s alter magazines, Analog, in 1967. Sheldon wrote under the pseudonym James Tiptree Jr, saying: “A male name seemed like good camouflage. I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed. I’ve had too many experiences in my life of being the first woman in some damned occupation.” It wasn’t until 1977 that it became widely known that Tiptree was actually a woman.

All of this contributed to the idea of science fiction being a boy’s club, and a white boy’s club at that. But what Nevala-Lee’s book does is put the spotlight back on women who have been airbrushed out of most official histories of the Golden Age, particularly Campbell’s first wife Dona, Heinlein’s first wife Leslyn, and perhaps the true hero of the story, Campbell’s assistant Kay Tarrant.

All of them were instrumental in keeping Astounding afloat in the early days; indeed when the war arrived and all four of the principal male characters in this story had to interrupt their careers to join up, Robert A Heinlein wanted to get Dona and Kay appointed editors of the magazine in his absence.

Campbell generally referred to Kay Tarrant as his secretary, but in truth she did the lion’s share of the work, going through fiction submissions for Campbell to approve, overseeing proofreading, copy-editing, administration and production of Astounding and Campbell’s other magazines, a job she did for 30 years.

The science fiction world that Campbell and his stable of writers created endured for years, but he began to lose touch with the genre especially as the 1960s dawned. The world was changing and Campbell’s white, male enclave was becoming increasingly irrelevant. A new sort of science fiction was emerging, which was dubbed New Wave. Just as, a decade later, punk would sweep away the pomp of prog rock, New Wave tackled all the things that Campbell thought were anathema in science fiction – sex, gender, drugs, post-modernism, politics – and mocked the stout, square-jawed heroes of the pulp years.

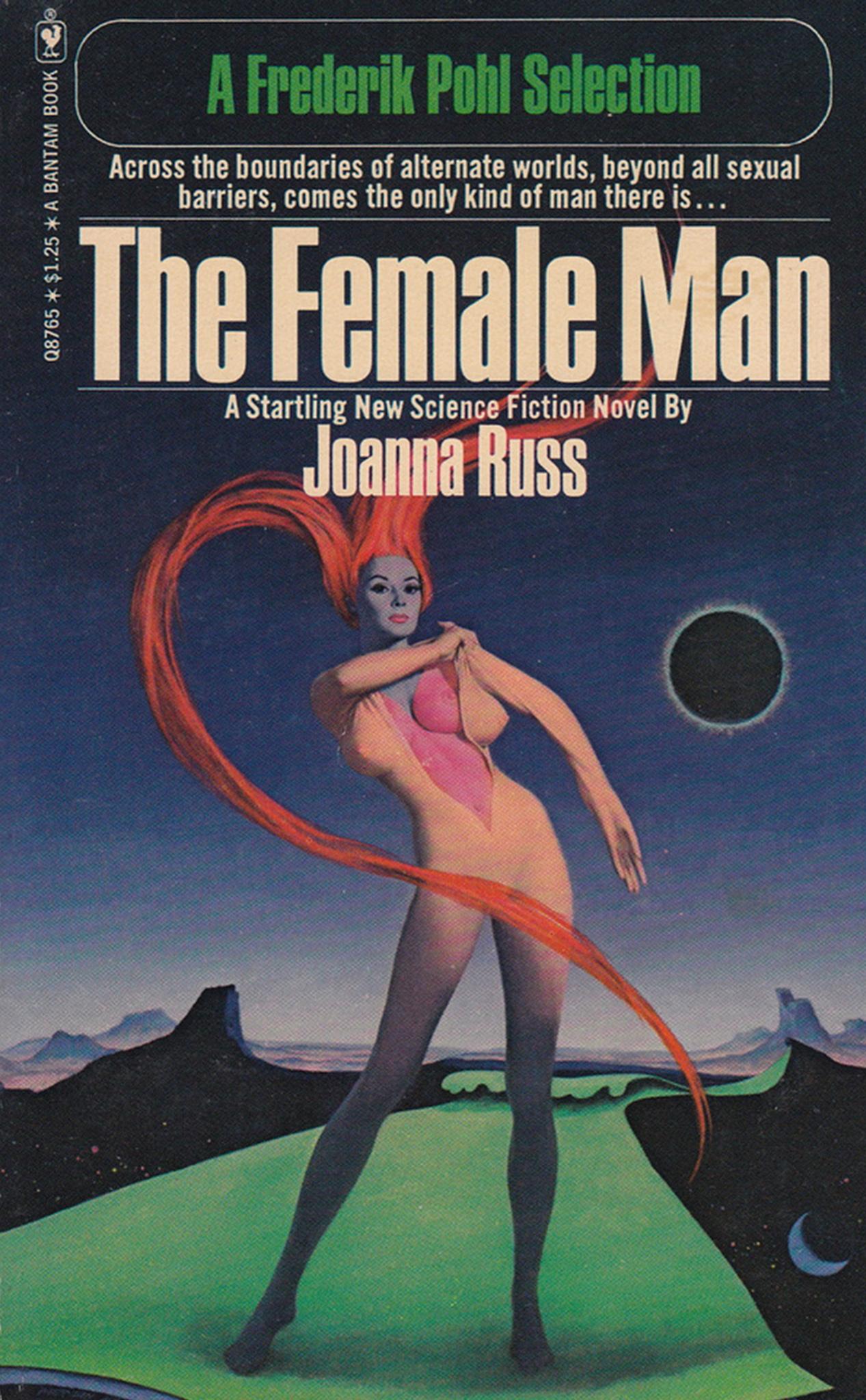

Women writers, so long kept in the shadows of science fiction, began to emerge and thrive. Writers such as Joanna Russ and her novels, including The Female Man, gained prominence, and in this period Ursula K Le Guin began to achieve what would be a climb towards a place at the very top of the literary world.

New Wave burned brightly, but for a relatively short period, into the 1970s. It did not perhaps herald the dawn of a new, equitable, diverse age as many hoped, at least not straight away. But it did demonstrate that a democratisation of science fiction was underway, and the grip of Campbell was loosed and eventually lost.

Nevala-Lee says: “Science fiction is too large now to be directed or defined by any one person, but this book concentrates on a period in which one man was thought to oversee it – until many of his readers broke free. Campbell liked to say that the genre’s true protagonist was all of mankind, but he saw it in terms of heroic figures, starting with himself.

“If his audience ultimately refused to fall in line it led, paradoxically, to the outcome that he wanted. Science fiction became an ongoing collaboration between writers and fans, and the most convincing proof of Campbell’s success is that he lost control of it.

Despite his viewpoints on so many things, Campbell is still revered today as one of the founding fathers of contemporary science fiction, as are his collaborators Asimov, Heinlein and Hubbard. To say they were all, in their own ways, problematic is an understatement. Asimov is considered one of the all-time greats, but Nevala-Lee outlines in detail his proclivity for pinching women’s behinds at science fiction conventions, something he seemed to see as a bit of fun but which, quite rightly today, would have him marked out as a serial assaulter.

What would Campbell have made of NK Jemisin’s multiple Hugo Award wins? We can only guess, along with his thoughts on the success of authors such as Nnedi Okorafor, or Kameron Hurley, or Ann Leckie, or any of the women who are currently dominating science fiction with female-led stories that upend expectations and blast the traditional old tropes so beloved of the Golden Age into the sun. We can only guess, but it’s fair to say that his thoughts would not have been very pretty.

And that’s not to say that the battle is won. In recent years there have been attempts to lead a backlash against the increasing diversity in science fiction, especially in America where concerted campaigns to keep the likes of Jemisin off the awards ballots have been prevalent, orchestrated by white men who miss the days of robust, heterosexual heroes rescuing grateful, lissom women from the clutches of salacious alien marauders. Indeed, one of these campaigns overtly called for “a Campbellian revolution” in science fiction.

John W Campbell is one of those figures around who the argument will endlessly rage about whether it is possible to celebrate the art from the artist, whether his views perpetually colour his achievements, or if we can or cannot deny the effect and influence he had on the science fiction genre, and whether it would be the same without him.

And, in the end, it doesn’t matter. Campbell was what he was, and he did what he did. He didn’t create science fiction, nor did he own it. It was an important period in history, but one that has passed. Science fiction today is new and wondrous and inclusive, and perhaps, in years to come, historians will be referring to this, not the Campbell era, as the true Golden Age.

‘Astounding’, by Alec Nevala-Lee, is out now, published by Dey St Books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments