‘It was wholesale slaughter’: The forgotten history of the plumage trade and the women who brought it down

Years before the feather hat-adorned suffragettes arrived, a group of Victorian women changed the face of conservation at a time when women’s voices were rarely heard. So why have they been all but wiped from history? Ashley Coates revisits the RSPB’s founding females

Few people are aware that the RSPB, Europe’s largest conservation organisation by membership, was founded by Victorian women working to end the cruelty of the feather trade.

Established in a house in Manchester 130 years ago this year, the Society for the Protection of Birds was initiated by Emily Williamson, the wife of a middle-class solicitor. An organisation with the same aims, known as Fur, Fin and Feather Folk, was set up in London by Eliza Phillips and merged with the SPB in 1891.

Active years before the suffragette movement, Emily Williamson, Eliza Phillips and the fastidious campaigner Etta Lemon, were far-sighted activists who utilised all the tools of communication available at the time, successfully capturing society’s hearts and minds and helping to bring about a change in consumer behaviour as well as some of the first laws to protect wildlife.

Their lives, and their contribution to conservation and to feminism, have been largely overlooked by historians and forgotten by the environmental movement. It was a story almost lost entirely to history prior to the publication of Tessa Boase’s revelatory book Mrs Pankhurst’s Purple Feather, released last year.

“These women (unlike Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst) didn’t covet publicity, fame or glory for themselves, and their hard-working anonymity has not served them well over time,” Tessa Boase suggests. “Not one of them put herself forward as a saviour of the birds.”

It is a neglected part of social, cultural, political and environmental history that has useful lessons for anyone engaged in conservation and activism. Now the campaign and the women who ran it, as well as the cruel trade that the society was created to oppose, ought to be getting better recognition.

A campaign against plumage in hats may seem obscure today but the demand for both local and exotic feathers for hats was huge in the late 19th and early 20th century.

“You could have a whole bird on your head,” Merle Patchett, a University of Bristol historian and expert in the feather trade, tells me. “The hat could include their heads and wings, or multiple species of bird on the one hat. You had what we would now consider quite Frankenstein creations.”

It supported a vast industry, much of which was centred in London, with birds shipped into Britain from across the tropical areas of the British empire, and North America. According to the writer and biologist Dennis Holley, a single order of feathers placed by a London dealer in this period included 6,000 bird of paradise feathers, 40,000 hummingbird feathers and 360,000 feathers from various East Indian species.

William Hornaday, the first director of the New York Zoological Society, dubbed London as “the mecca of the feather killers of the world”. Hornaday stated that London took delivery of 130,000 egrets in one nine-month period at the tail end of the 19th century. Even the beautiful birds of paradise were not spared: Hornaday’s studies held that in one auction in February 1911, 1,920 skins of the bird of paradise were put up by just four traders.

“I was absolutely astonished at its scale,” author Tessa Boase says. “The auction figures alone are mind-boggling. Wholesale slaughter was going on, and yet we know nothing about it today.”

Although habitat loss and deforestation also played a part in their demise, hunting for the colourful feathers of the passenger pigeon and the Carolina parakeet was a factor in the extinction of these species, in 1914 and 1910 respectively.

Other species lived on but had their numbers greatly reduced, the grebes and the egrets being particular targets. The great crested grebe, probably one of the most impressive bird species in Britain due to its ornate head plume, was almost brought to extinction in Britain and Ireland.

“There are a lot of conversations about when the Anthropocene really started, and you can see the plumage trade as an early warning sign of the sixth mass extinction,” Patchett suggests.

By 1900, it was estimated that around 5 million birds were being killed every year to service this industry, dubbed by the early SPB campaigners as “murderous millenary”.

Not all of the birds were killed for their feathers, some had their wings removed while they were still alive. Many of the birds that met this end were killed during the nesting season, leaving young birds to fend for themselves.

Much like the trade in turtle meat, it is probably the absence of any remnants of this industry that means it has been so completely forgotten about. Very little is left to remind anyone of the scale of the plumage trade, and the impact it had on bird populations.

It was against the backdrop of this huge and destructive trade that in 1889, the Society for the Protection of Birds was established with the following rules:

- That members shall discourage the wanton destruction of birds and interest themselves generally in their protection;

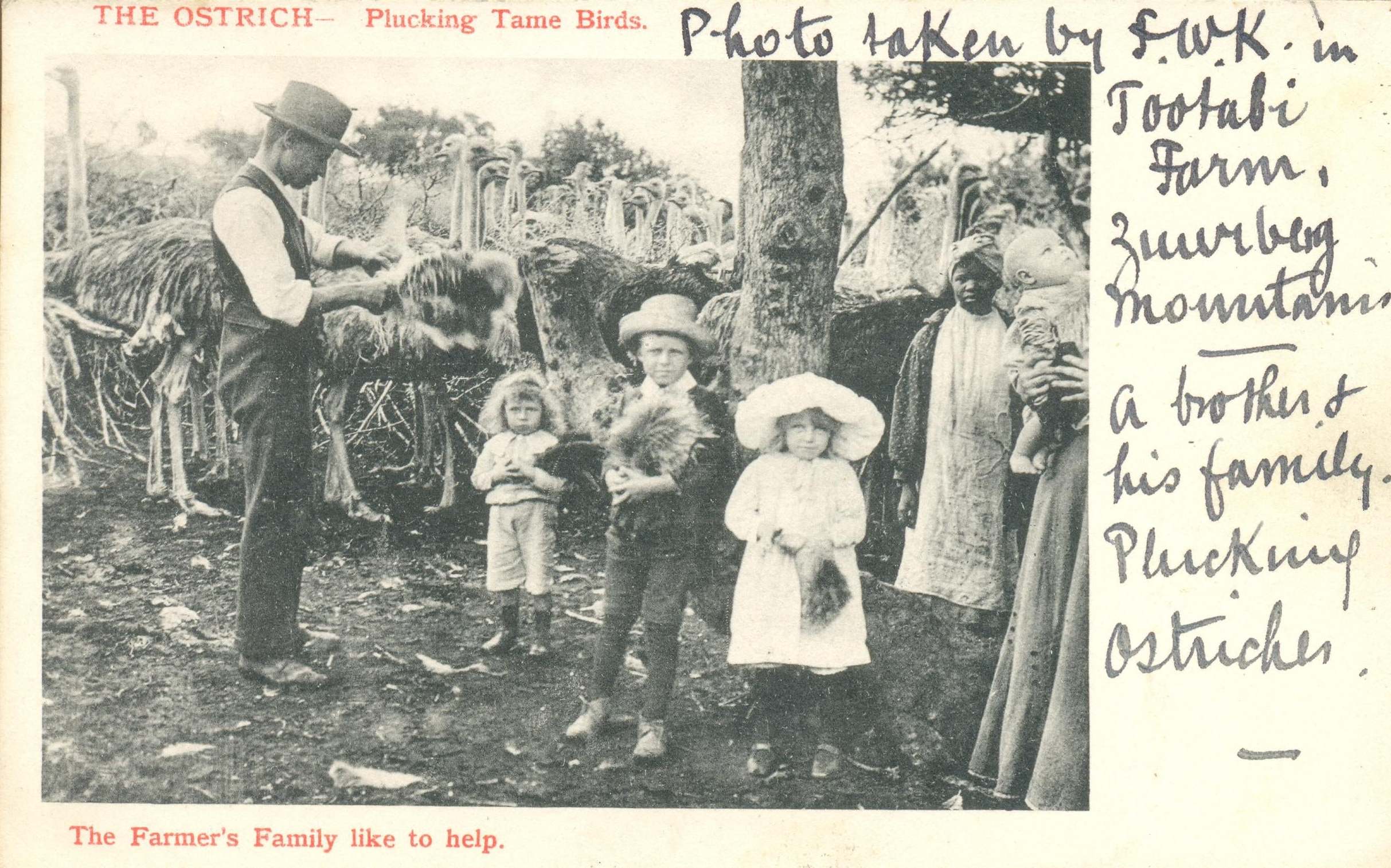

- That lady-members shall refrain from wearing the feathers of any bird not killed for purposes of food, the ostrich only excepted.

The exemption of ostrich feathers later became a bone of contention within the society but merited an exclusion from the rules as ostriches were, in the late 19th and early 20th century, farmed for their feathers.

Having originally been hunted for their feathers, an “ostrich incubator” was set up by entrepreneurial colonists in the Cape to establish an industry for the feather. First successfully implemented in 1869, the incubator meant the means now existed for farmers to hatch multiple eggs simultaneously, and ostrich feather went on to become one of South Africa’s most valuable industries.

In its early years, the SPB consisted almost entirely of women. Emily Williamson, Eliza Phillips, Etta Lemon, the Duchess of Portland, and the dozens of women who assisted them, were fighting for a change in consumer behaviour and in legislation at a time when women were yet to secure the right to vote, let alone successfully run a campaign aimed at delivering a major change in the law.

They used pre-existing networks to spread their message, as well as their own network of branch secretaries, tasked with onboarding new members committed to not wearing feathers.

Although they were successful in gaining press attention, not all of the attention was complimentary. The SPB was criticised for being too ambitious, and too lightweight, usually by men. It was derided and patronised in much of the media, and (for a time) sidelined by many in the ornithological community who, Boase notes, were “deeply proprietary in nature”. Birds belonged to the men of science, in the view of many at the time, not the women bird lovers.

They were brave women, who went up against not just other women of their own class, but a powerful and highly profitable industry and the social norms of their time. In an era when plumage was all the rage, and the class system held a grip on British society, these early conservationists ran the risk of social exclusion and this created tensions within the fledgling group. One member repeatedly raised the question of hunting for game birds at the society’s AGMs, only to be politely ignored.

“I think they were held back by their class,” says Tessa Boase, “both for not being able to tap into working-class circles very effectively, and for appearing like another finger-wagging campaign from the likes of the Temperance Society, denying working-class women a bit of frivolous fun.

There are a lot of conversations about when the Anthropocene really started, and you can see the plumage trade as an early warning sign of the sixth mass extinction

“I wish they had been more radical – perhaps marching on the streets themselves! But they were who they were, and within their social constraints they were actually very brave in what they did. The ‘osprey’ campaign (egret feathers) was hard-hitting and uncomfortable for all concerned, but the local secretaries were compelled to see it through. They paved the way for the radical suffragists.”

The society experienced a rapid increase in membership and widespread support for its aims, and after just 15 years of operation, it was granted a royal charter by King Edward VII in 1904. By 1908, it had 20,000 members and had distributed over 50,000 leaflets. It spread around the world, or at least the British empire, laying the foundation of the organisation’s role in global conservation today.

The Importation of Plumage Bill, banning the importing of feathers into Britain, was first brought to the House of Lords in 1908. Its passage was extremely slow, largely due to vested interests that continued to support the trade. But although the plumage industry continued after a brief ban during the First World War, its heyday was over. Concerted campaigning by the SPB, support for the campaign by Nancy Astor in parliament, and a highly influential essay by Virginia Woolf, all helped to bring the trade to an end. The bill finally passed in 1921.

“There was a gradual tailing off,” Patchett tells me. “The First World War really hit it and after the conflict there was a real change in the way women dressed, with a move away from the massive Edwardian hats towards more of a subdued and streamlined aesthetic”.

Woolf’s essay sought to correct the mental disconnect many shoppers had between the feathers they bought in shops from the birds they were sourced from.

“She creates a figure called lady-so-and-so, depicted as a member of the upper classes, looking into shop windows in London for the finishing touches to her opera attire, and then she switches to the Argentinian Pampas where these birds are being slaughtered, and the young left to die.

“You have this really interesting geographical shift from the streets of metropolitan London, to the places where they are being killed.”

Support for the bill was also helped by the passage of the Migratory Bird Act in the United States in 1918. In a curious case of histories running in parallel, the efforts of Eliza and Emily were mirrored in the US with a similar campaign run by Bostonian women, Harriet Hemenway and her cousin, Minna Hall. During a campaign that featured many of the same challenges, tactics and society pressures, Hall and Hemenway had successfully pitched themselves against the plumage industry in the US, where a significant percentage of the hunting of birds was taking place.

These women (unlike Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst) didn’t covet publicity, fame or glory for themselves, and their hard-working anonymity has not served them well over time. Not one of them put herself forward as a saviour of the birds

Much like the early SPB, their advocates were, initially, the very upper crust of society. When launching their new group, Hemenway and Hall took to Boston’s “Blue Book”, a social register of the local great and good.

The pair organised tea parties, where their contemporaries could learn about the plight of the nation’s birds and commit not to wear feathers in their hats. Many of the women who attended these tea parties refused to engage and left the gatherings, but many didn’t, and the group soon had 900 highly influential supporters. Massachusetts banned the wild bird feather trade in 1897; national commitments to do the same would come later.

Hemenway and Hall have also left the legacy of a thriving conservation organisation, the Massachusetts Audubon Society and their actions were influential in the establishment of the National Audubon Society.

The American writer Kate Kelly notes: “Within a couple of years of the founding of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, bird lovers of Pennsylvania, New York, Maine, Colorado, and the District of Columbia followed the example set by Massachusetts.

“In 1901 Florida voted to protect the badly decimated nesting spots in the Everglades. Hemenway eventually helped establish a national network of the societies.”

They too led a campaign which sits firmly within the category of “little known/forgotten” histories.

Despite the high-profile extinction of the great auk in the preceding century, the women of the SPB (and their American counterparts) were campaigning during a period when few people believed that humans could bring about significant environmental degradation, nor was there widespread concern for the rights of animals on the scale we see today.

The way in which we come to value history is influenced hugely by our surroundings and what we are taught as children. The great political figures of the last century are memorialised across the country. They are present in our syllabuses, in memorials, statues, plaques on buildings. They live on in our contemporary culture.

As we move into a period where we recognise the full extent of the mass extinction caused by human actions and what we need to do to stop it, it also makes sense to ensure we give proper recognition to the people who started the pushback against our outright exploitation of nature.

The world of conservation only has a few recognisable heroes, household names such as Jane Goodall and Gerald Durrell, the broadcasters Sir David Attenborough and Chris Packham. It is time for the women of the RSPB to join their ranks.

“Etta Lemon’s former home in Redhill should have a plaque,” Boase says. “I’m trying to set this in motion and the family living there is keen. But something more public and obvious would be good for both Frank (her husband) and Etta Lemon, both so entwined with the RSPB.

“Eliza Phillips is also due some kind of memorial, and Croydon RSPB is investigating what might work, and where.”

One long-overdue act of recognition has now taken place. On 1 June this year, a plaque for Emily Williamson went up at her old house in Manchester (The Croft at Fletcher Moss, Didsbury).

Of the many lessons that we can take away from the campaign, one that seems particularly important for today’s environmental crisis, is how strong social conventions that damage the environment can persist as mainstream behaviour. In the early days of their campaigns, the SPB were seen as extremists and a nuisance, wagging their fingers at innocent hat wearers who were just trying to get on with their lives.

Today no one would turn up at a social engagement with most of a dead bird on their head. As the Anthropocene continues apace, it is worth reflecting on how the seemingly normal behaviours we engage in today could become unacceptable in just a few years’ time.

Boase is now engaged in a lecture tour that raises awareness for the society’s early efforts. I asked Tessa what she thinks we can learn from the women she brought to light in her book.

“I think the greatest lesson is never give up. People might laugh at you, ridicule you (Greta Thunberg springs to mind), you might feel you are a tiny drop in the ocean, pushing against a force far, far greater than you; believe in your campaign, and keep on pushing.

“Build numbers by tapping into like-minded groups already existing. Think nationally (or globally): get local secretaries, or similar, to co-opt new members and spread the word. Social media does this far faster, of course, today. And remember that campaigns started by women stand a far greater chance (statistically, according to change.org) of success.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments