17 June 2006: Why is great art rarely a box office hit?

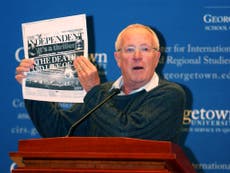

Here Robert Fisk has multiple questions on his mind – Is it talent or genius that decides art’s place in history? Or is it history itself?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I once had to review a biography of that upstanding Palestinian academic and peace proponent Hanan Ashrawi, but admitted at the start of my article that it was almost impossible to write because the book was so unmitigatedly awful.

Now I have forced myself to see The Da Vinci Code, I have reached a new literary crevasse, the near-inability to speak of this film, based – as we all know – on the novel by the exotically named Dan Brown.

God, it’s awful! How His Holiness, the famous anti-gay, anti-divorce, anti-aircraft gunner Pope of Rome could have been so upset beats me, because the film makes the Roman Catholic church even more boring than it actually is. “Roman mumbo-jumbo” is how my elderly dad used to talk about the rites of the Catholic church and it’s not a bad description of this ghastly movie. For its popularity symbolises not our interest in Christ but our lack of faith, our desperate need for bunkum religion. It’s actually about black magic.

The film steals shamelessly from the work of others. The face masks and the ghostly siege of Jerusalem – complete with ballistas, although the Muslim armies have been replaced by Crusaders – are cribs from Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven. Some of the music sounds unnervingly close to the score from Scott’s Gladiator. And as the actress Nelofer Pazira has pointed out, the flagellating murderer is almost identical – in character and physical likeness – to the figure of Death, played by Bengt Ekerot in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. Remember the famous chess game between Ekerot and Max von Sydow’s Crusader knight?

But it all raises an ancient question. How come this pap is so popular while great art and literature and music – and movies – are rarely if ever box office? How come the books and the films and the music which we are supposed to admire don’t receive the world’s admiration – or at least millions of dollars – while chick-lit and Paris Hilton and, yes, The Da Vinci Code pack them in from Singapore to Denver? Are we really just tools of the marketing boys who push this stuff like preachers or like the Wild West quack doctors who promised eternal youth in a bottle?

Let’s start, though, on the side of the bad guys. The Independent once ran a review of James Cameron’s Titanic under the headline: “I’ve seen Titanic – and it stinks”. Now I liked Titanic – just as I admired Scott’s snottily reviewed Kingdom of Heaven – and I still remember its best line, when the gorgeous Rose (Kate Winslet) asks Andrews, the ship’s Irish designer, if the vessel will sink: “Mr Andrews, I saw the iceberg – and I see it in your eyes.” And when the Titanic goes down, along with Andrews – the real-life brother, as it happens, of one of Northern Ireland’s Protestant prime ministers – by heaven, you felt as if you were going to the bottom of the Atlantic with it.

And I remember with great fondness the long nights in Ireland when I was completing my PhD thesis (subject: Irish neutrality in the Second World War) at the window of a cottage immediately opposite another terraced home in which that most prolific of Irish writers, Maeve Binchy, was finishing her beautiful novel Light a Penny Candle. Like so much of Binchy’s output, Candle was regarded as unworthy of serious critical attention, even though several scenes in the novel – the terrible moment, for example, when an Irish couple realise (while the reader does not) that their daughter has stolen the Christmas present she is giving them – are Dickensian in their pathos. Yet Maeve is not placed alongside literary prizewinners like her much less-read but near-neighbour novelist John Banville. Conversely, John Banville – the man who asked me to review the Ashrawi biography for The Irish Times – is not going to rake in the kind of profits that Maeve makes.

What, then, makes art popular? When I went to school, Charles Dickens was frowned upon as a fusty old Victorian who churned out pot-boilers for weekly newspapers (all true), even if his characters – Pip, Scrooge, Oliver Twist and the rest – were immensely popular with children. By the time I reached college, however, the very same Dickens appeared in every modern literature course – Dr David Craig, formerly of Lancaster University, please note – as a pseudo-leftist laying open the scandals of the Industrial Revolution (Hard Times and Bleak House).

Equally, when I was at school, I developed a passion for largely ignored composers, boring my parents to genuine tears with scratched but booming records of Bruckner and Shostakovich. Now they are flavour of the month all year round and the Leningrad is almost as overplayed as the masterpieces which Your Hundred Best Tunes turned into clichés: Beethoven’s Fifth, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, Sibelius’ Finlandia, Chopin’s preludes, Handel’s Water Music, Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons and the other “pops” which have me reaching for the “off ” button as surely as if they were Carly Simon.

Clearly, there are no set rules for all this. Verdi was as popular in his time as he is among opera-goers today. The Godfather crossed the line between popularity and art quite effortlessly. So has Hitchcock. Casablanca was as popular in 1941 as it is now, albeit for different reasons. David Lean’s Dr Zhivago was immensely popular in the cinema; my Dad loved it, but oddly regarded the original Pasternak novel – infinitely more moving and tragic – as the success of “those damned publicists”.

But my dilemma remains. I love the poetry of Seamus Heaney, but regard Bomber, an account of an RAF fire raid on Nazi Germany, as one of the best novels of war – even though it was written by the distinctly un-prized and overread author Len Deighton. John Le Carré’s spy Smiley has clearly moved between art and mass appreciation (though not with me). Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai made the same leap of imaginative and popular faith, though at the cost of relegating Pierre Boulle’s original novel – with its much more painful ending, because the attack on the bridge is a failure – to an intellectual retreat.

Is it talent or genius that decides art’s place in history? Or is it history itself? Must authors and directors and composers match their work to the age they live in? Must we wait for a “War on Terror” symphony, a “9/11 Suite”, an “Iraqi Requiem” to match Shostakovich or Barber or Britten? As for The Da Vinci Code, heaven preserve Sophie, the French police cryptologist who turns out to be Jesus Christ’s only direct blood relative left on earth.

She ends the movie with a stigmata on her neck of the kind that the Holy Father was once trying to inflict – unwillingly, of course – on RAF crews over Nazi Germany. Popular movie? Merde!

Following the death of Robert Fisk on 30 October 2020, The Independent has reproduced some of his best dispatches from 30 years of reporting

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments