‘Youth that dying touch my lips to song’: The poetry of men who loved men in the First World War

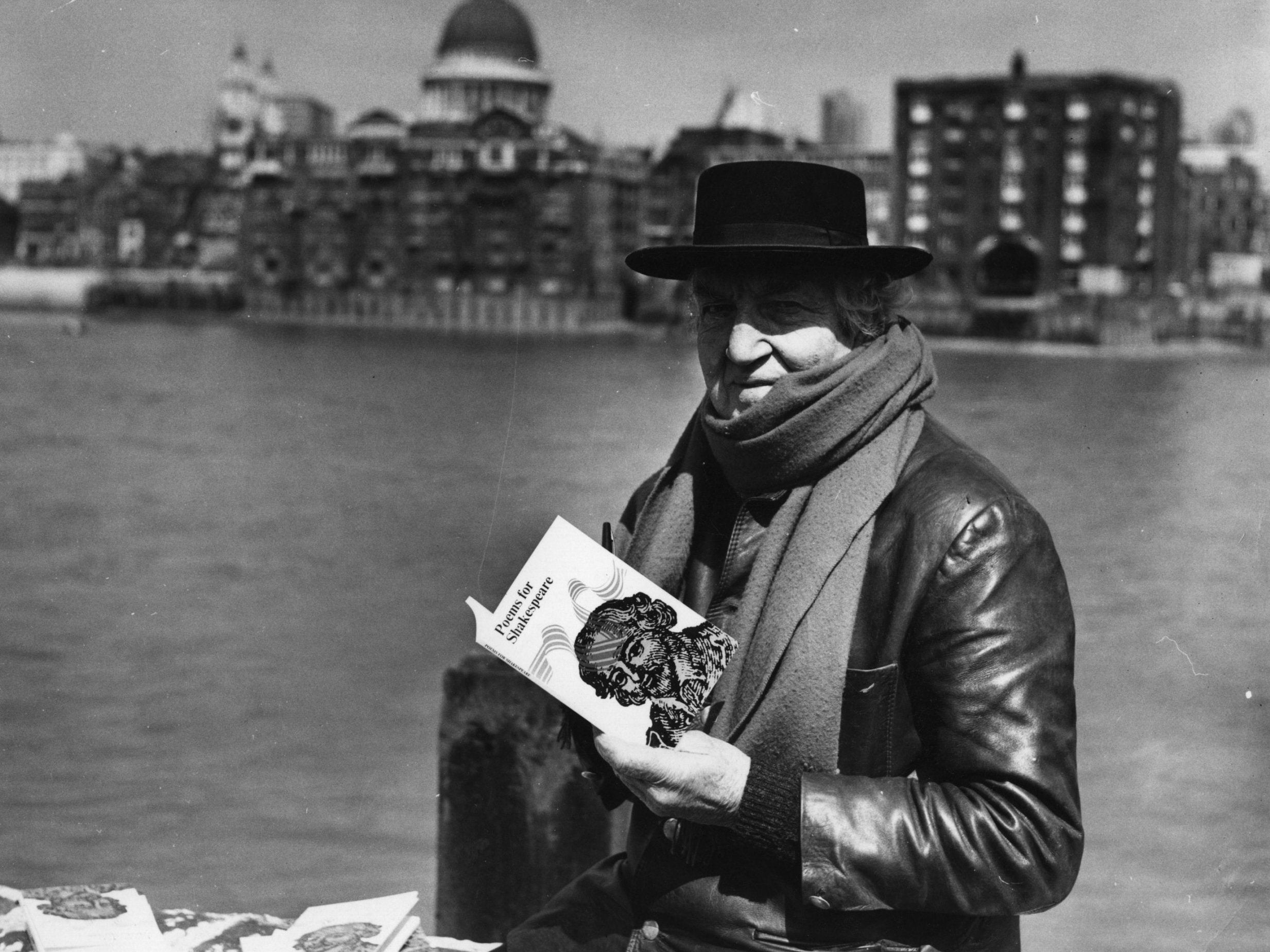

Our understanding of the Great War has been shaped by its poets. As Kevin Childs explains, their passions were complex, desperate and tragic; yet their words were underpinned by beauty as much as by horror

Only, I think, once or twice does one stumble across that person into whom one fits at once: to whom one can stand naked, all disclosed. – Charles Hamilton Sorley

Charles Hamilton Sorley was convinced he would “stumble across” love, but for much of his time in the trenches in 1915 it was the closeness of camaraderie, the “second best” sort of love, that triggered feelings in him: the “friendship of circumstance” could look a lot like the real thing. Both kinds of love were a preoccupation for the soldier poet of the First World War; something shining in the earth – a promise, a consolation for the brutalities imposed by king and country.

Our instinctive connection to that long-off war is the poetry of the trenches, not the history books. Why can we not think of war now without a line or two of Owen or Sassoon or Sorley dropping into our heads? Owen, Sassoon, Graves, Gurney, Sorley, even Brooke, are our guides to that brutal conflict; great poets all, but also lovers – lovers of men, lovers of male bodies, male sweat, male breath, seeking the one in front of whom they might stand naked, “all disclosed” 100 years ago.

The tendency to generalise during First World War commemorations means it’s easy to evade the nature of the relationship between poet and subject which, in the end, drives what Wilfred Owen termed the “pity of war”: love, longing, lust, rage, despair, “the rough male kiss of blankets” and the “youth that dying touched my lips to song” all inter-mingled. For isn’t love to be found in the red mouths and red wounds and pale young faces peering out from under a steel hat? Isn’t it in the winding of puttees over a strong calf, the muddy fingers parting dirty blond hair, the clear blue eyes half-lidded over a smile? Above all isn’t it in the boy who died last night while laying new wire across no-mans land; the athlete who read Homer and loved Housman; the sensitive lad who hid a copy of Wilde’s ‘Ballad of Reading Gaol’ in his knapsack; the young men who might be “so” in the jargon of the time?

“Adieu! or (chances three to one in favour of the pleasanter alternative) auf wiedersehen! Pray that I ride my frisky nerves with a cool and steady hand when the time arrives. And you don't know how much I long for our next meeting…”

Sorely, only 20, wasn’t sure he was up to the awful job he’d been given, commanding men in battle, and he wanted nothing better than “our next meeting”. The letter was written to Arthur Watts, whom he’d met and spent a glorious summer with in Germany in 1914, an English lecturer abroad then, now an intelligence officer at the War Office, who was that “person into whom one fits at once” – “you were 40 when I first saw you; 30, donnish, and well-mannered when you first asked me to tea; but later, at tennis, you were any age… after all, friends are the same age”.

When you see millions of the mouthless dead... Say not soft things as other men have saidThat you’ll remember

Towards the middle of October 1915, as night fell, Sorley’s battalion of the Suffolk Regiment slipped into the front-line trenches just north of Loos, near the French border with Belgium. Plans had been laid. Another strip of land had to be taken in the long, inexorable grind of war. At noon the next day a two-hour bombardment began of a double trench called the Hairpin; boom followed boom, black earth was thrown up and fell like brittle ash, the air was filled with flashes and shrieks and war smog.

And then, a delay, as orders didn’t come for nearly 15 minutes. By the time the men went over the top – and those moments of dangerous silence came to an abrupt end with whistles blowing and war cries going up – they were charging into rapidly thinning smoke. The air cleared. Machine guns cackled from a German post, opening bloody holes in the Suffolks’ lines. Sorley’s company was held up by German wire and one or two fatally expert bombers. His commander fell, he pushed forward to open a gap into the trench to let the soldiers do their work, and for a few seconds a sniper had his fine young head in his sights. A crack. Temporary Captain Charles Hamilton Sorley fell forward, his head broken, his heart stopped.

When you see millions of the mouthless dead

Across your dreams in pale battalions go,

Say not soft things as other men have said,

That you’ll remember. For you need not so.

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

No tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead.

Say only this, ‘They are dead.’ Then add thereto,

‘Yet many a better one has died before.’

Then, scanning all the o’ercrowded mass, should you

Perceive one face that you loved heretofore,

It is a spook. None wears the face you knew.

Great death has made all his for evermore.

– Charles Hamilton Sorley, A Sonnet

“I have just discovered a brilliant young poet called Sorley,” Robert Graves wrote to his poetical mentor Edward Marsh a few months later. “It seems ridiculous to fall in love with a dead man as I have found myself doing, but he seems to have been one so entirely after my own heart in his loves and hates, besides having been just my own age.”

Poet to poet, young man to young man, Sorley’s collection, Marlborough and Other Poems, had come into Graves’ hands – the little book ran to five editions before the end of May 1916 – and Sorley’s love of wild nature and ruthless reflections on war appealed. The sonnet beginning “When you see millions of the mouthless dead”, written only a short while before the poet’s death, was found by the Battalion Adjutant in his kit the day after he was killed. He sent it with Sorley’s other effects to his parents. The body was never found.

It was the Sorley who loved the English landscape, but hated English cant, who caught Graves’ attention; a clear-sighted, disconsolate and reluctant warrior for the country of his birth. “England, I am sick of the sound of the word,” Sorley told his father, going on:

“In training to fight for England, I am training to fight for that deliberate hypocrisy, that terrible middle-class sloth of outlook and appalling ‘imaginative indolence’ that has marked us out from generation to generation. Goliath and Caiaphas, the philistine and the Pharisee, pound these together and there you have Suburbia and Westminster and Fleet Street.”

His was the first expression in poetry of violent, meaningless, unheroic death, Sorley’s voice that of a good soldier in a bad war

His was the first expression in poetry of violent, meaningless and unheroic death. Sorley’s voice that of a good soldier in a bad war. Not long after the Marlborough collection was published, Sorley’s father received a letter from an unknown admirer, probably someone at the front, who felt he knew the poet in much the same way Graves did: “I have had it [the collection] a week and it has haunted my thoughts,” he said of the book of poetry. “I have been affected with a sense of personal loss, as if he had been not a stranger but my dearest friend… and surely no one was ever better worth knowing.”

Graves would ask Siegfried Sassoon whether he thought Sorley was “so”, meaning homosexual, concluding that he must have been as Sorley had never written even a “conventional” love lyric. And he felt justified in loving the cross-country youth running through squalls over the Downs, hair dripping over his eyes, jersey rain-soaked and clinging like a kiss, the song of the wind coming to him again in a mud-stinking dugout:

Yet rest there, Shelley, on the sill,

For though the winds come frorely

I’m away to the rain-blown hill

And the ghost of Sorley.

– Robert Graves, Sorley’s Weather

It’s a common notion that war transformed the art of the First World War poets. It’s an even greater commonplace that the war poets transformed the world’s view of war; war poetry before 1914 was written, by and large, by non-combatants drunk on dreams of honour, while by the time of the Second World War poetry was out of fashion, having become the preserve of an intellectual elite.

But 1914 was a moment when poetry and subject collided: new poets, new anthologies, many examining the greatest themes of all, love and war. Even so, there is a cruel irony in the fact that many of these poets were attracted to men, (or as Byron put it, “strongly, wrongly, vainly love”) and yet were teaching a world which, both at the time of the Great War and for much of the past 100 years, despised and persecuted them and their kind. What’s more, they were teaching the world to fall out of love with war.

Perhaps an even greater irony is that they were not shy of expressing their love to that otherwise unfriendly general public: not a vague, “we’re-all-in-this-together” sort of love, the sentimental feeling a commanding officer might have for his men, but searing, passionate, tender, laughing, cruel love that would not let them sleep at night, the loss of which drove men mad:

Move him into the sun –

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields unsown.

Always it woke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

– Wilfred Owen, Futility

At home, on leave, in the busy metropolis, on a troop ship, in a dugout, the mind drifts to the lovely lad who is universal and specific; an idealised dead poet, a cricketing second lieutenant, a soldier servant with gentle hands, a critic wise beyond his years, the youth beside you in the line. Even the everydayness of life in the trenches offers moments of cerebral erotic pleasure, and sexual tension lurks beneath the surface of a poem like Graves’ ‘Sorley’s Weather’ as much as it does Owen’s ‘Futility’ and the most harrowing of trench verses.

“Whether the expression of love in these poems was intended to be platonic or sexual,” wrote Martin Taylor in the introduction to his 1989 anthology, Lads: Love Poetry of the Trenches “…it was all, nevertheless, the expression of some kind of love; and the intensities of emotion involved render them suitable for inclusion under the banner of homoeroticism.”

But what encouraged Graves and Sassoon, Owen and Ivor Gurney and kept them going, often returning to the trenches when there was strictly no need or defying public opinion, if not their capacity for love? Edward Carpenter, the prophet of homosexual liberation, wrote in 1908 that homosexuals were set apart with particular gifts for art and poetry, their role to teach the world to love.

Sassoon and Graves and Owen, all of whom read this, no doubt believed it too. They were gay men who loved the men they stood with in a theatre set apart from the ordinary. It was their purpose, their right, if you will, to crystallise that love, and poetry was still the language of love in 1916, even if it was also the language of war.

* * *

Sassoon and a young fellow officer, David Thomas, would ride out together during off-duty moments, following tracks through the woods near Montagne, Sassoon hollering as if on a make-believe hunt, “losing our fox when the horses had done enough galloping. An imaginary kill didn’t appeal to me somehow.” One afternoon in 1916 on borrowed horses they rode to a nearby village where they stopped for tea and cakes – “as good as anything in Amiens”.

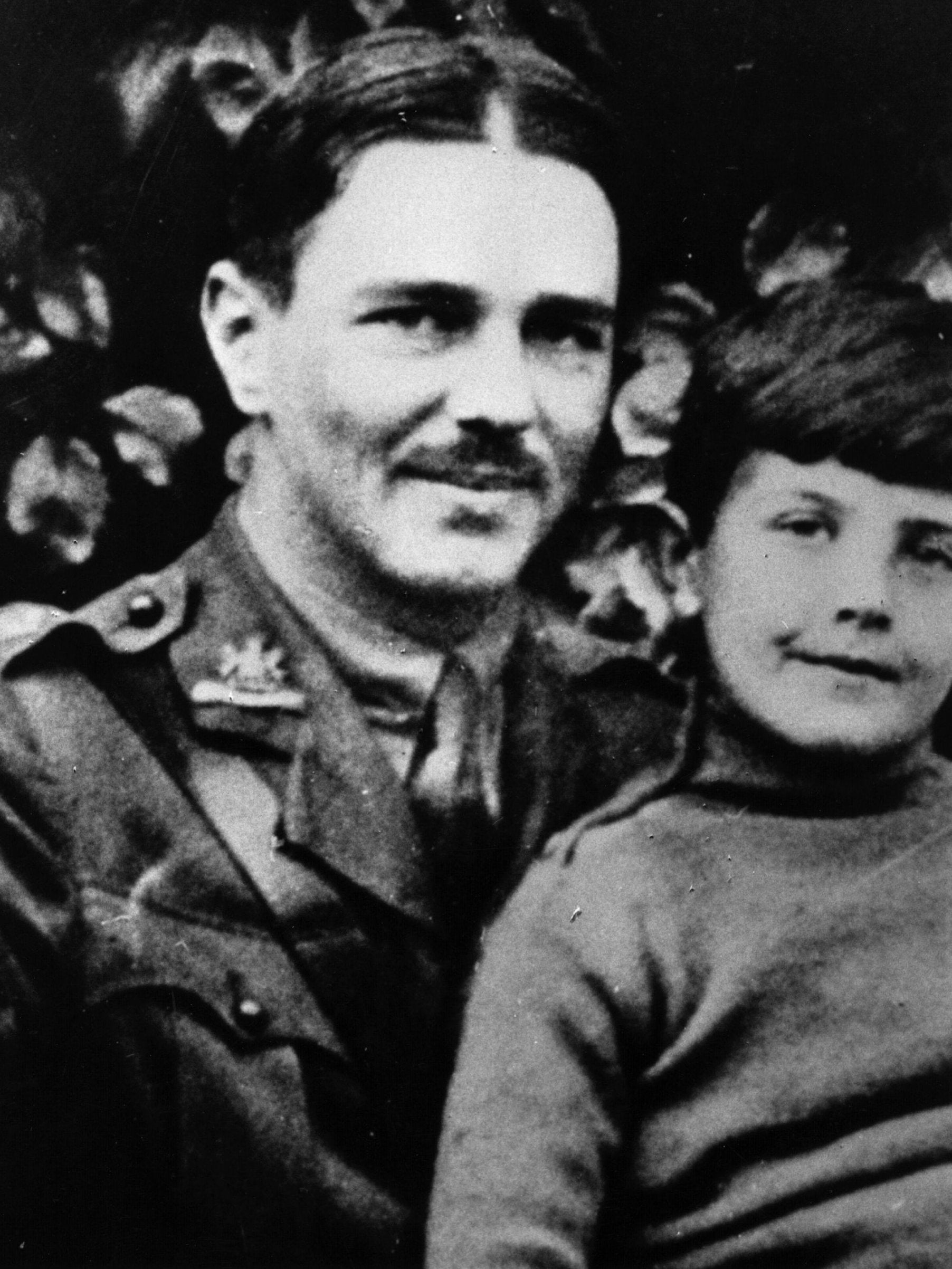

Second Lieutenant Thomas was 19 years old, a parson’s son from Glamorgan, flaxen haired, fresh faced, an athlete who read poetry and talked about Homer. He’d met Sassoon the previous year at training camp near Liverpool after a game of cricket and, during an idyllic few summer weeks billeted in Cambridge, Sassoon had fallen madly in love, perhaps even letting on – although he kept an unspoken vow of celibacy throughout the war and Thomas was almost certainly too coy.

The jealous Graves called him “a simple, gentle fellow, fond of reading,” but was half in love with the Welsh Apollo himself. At about this time Sassoon wrote several poems in which Thomas, or “Tommy” as he was affectionately known, figured largely, often a sort of thing of earth, wind and fire, sometimes a representative of the type of young man who has been sent to war in the fever of duty and mass volunteering but for whom the world ought to have provided a better alternative.

The new commanding officer of the Royal Welch Fusilier 2nd Battalion, Major Clifton Stockwell, was fretting about the state of the frontline on their return from riding, ordering wiring parties to repair and relay along the stretch near Mametz Wood. One sharp night not long after, David Thomas was out laying new wire in the gaps made by crump holes. The air was bitter, even under thick gloves the men’s fingers ached; the sky was clear and starry, and there were shadows on the ground in the tangle of Bosch trenches ahead.

One such detached itself from the general gloom. A rifle snapped and Tommy fell on the wire, shot through the throat. He wouldn’t risk the lives of stretcher bearers but managed to make his own way back to the trench and found a first aid post. “They came afterwards,” Sassoon wrote in his diary, “and told that my little Tommy had been hit by a stray bullet and died last night. When last I saw him, two nights ago, he had his notebook in his hand, reading my last poem…. Now he comes back to me in memories, like an angel, with the light in his yellow hair….”

Thomas was buried at night with little ceremony, amid the chatter of machine gun fire. “A sack was lowered into the ground. I knew Death then,” Sassoon wrote later; and as if on cue a trench mortar exploded a short distance away, “spouting the earth up with a crash”.

At first words wouldn’t come: the legend of “Mad Jack” Sassoon of the Battalion grew from it, sneaking out night after Stygian night to lob bombs at German trenches in a sort of fury of retribution. Finally, poetry came: in ‘'The Last Meeting'’, he mourns the lovely Thomas as a young god returned to nature, death a vital dilation into something elegiac, pastoral, metamorphic. Sassoon goes searching for Thomas among the places of human habitation: by a mill, along the street of a nearby village and the ruins of an unfinished mansion “[a] little longer I’ll delay / And then he’ll be more glad to hear my feet”. But it’s only in the deep quiet of the wood that “there was no need to call his name. He was beside me now as swift as light”, and Thomas speaks to Sassoon finally as a beloved:

‘For now,’ he said, ‘my spirit has more eyes

Than heaven has stars; and they are lit by love.’

The transmutation is complete. Sassoon bids farewell to his beloved, knowing that he will always be there, having joined with the elements and the great, sad heart of the world:

Thus when I find new loveliness to praise,

And things long-known shine out in sudden grace,

Then I will think: ‘He moves before me now.’

So he will never come but in delight,

And, as it was in life, his name shall be

Wonder awaking in a summer dawn,

And youth, that dying, touched my lips to song.

– Siegfried Sassoon, The Last Meeting

Graves made a briefer walk in the woods, also mourning Thomas, but if there are echoes of Sassoon in ‘Not Dead’, Graves, like his mourning, is terser, simpler and less sentimental:

A brook goes bubbling by: the voice is his.

Turf burns with pleasant smoke;

I laugh at chaffinch and at primroses.

All that is simple, happy, strong, he is.

Over the whole wood in a little while

Breaks his slow smile.

– Robert Graves, Not Dead

Sassoon’s ‘The Last Meeting’, published the following year in The Old Huntsman, was among the poet’s final neo-pagan nature poems. From now on realism would become his god: “So, I wrote his name in chalk on the beech-tree stem,” he told his diary, “and left a rough garland of ivy there, and a yellow primrose for his yellow hair and kind grey eyes, my dear, my dear”; the final note so plaintive as to strike a sort of echo among the woods.

It is only fair to tell you that since the cataclysm of my friend Peter, my affections are running in the more normal channels... I should hate you to think I was a confirmed homosexual

In the spring of 1916 Graves was moving towards his own crisis of the heart. He’d spent much of his war so far sexually frustrated over an old Charterhouse School chum, GH Johnstone, whom he called Peter. His only real love poem of wartime, ‘1915’, is the fruit of this relationship, a love which, despite all the brutalities of a public school education and a devastating war, had remained romantic and ideal:

Dear, you’ve been everything that I most lack

In these soul-deadening trenches – pictures, books,

Music, the quiet of an English wood,

Beautiful comrade-looks,

The narrow, bouldered mountain track,

The broad, full-bosomed ocean, green and black,

And peace, and all that’s good.

– Robert Graves, 1915

Muse, comfort, lover and genius of the great outdoors, the young Johnstone’s “beautiful comrade looks” had been meat and spirit to Graves’s lonely self during his hard time at the frontline. So, it’s not difficult to imagine his dismay on discovering that Johnstone was no better than he ought to be, with needs and creeds that Graves had done his best to suppress or sublimate. His love staggered on for a few more months when, not long after these lines were written, Graves heard from an officious cousin that Johnstone had been arrested for importuning a Canadian soldier outside the gates of their school. Later he wrote coldly to fellow poet Robert Nichols:

“It is only fair to tell you that since the cataclysm of my friend Peter, my affections are running in the more normal channels... I should hate you to think I was a confirmed homosexual even if it were only in my thought and went no farther.”

The world shifts uncomfortably, idealised homosexuality becomes idolised heterosexuality, and a life-long vendetta against gay men is born.

By the time he encountered Sassoon at Craiglockhart Military Hospital near Edinburgh, Wilfred Owen was already confident enough to have no qualms about knocking on a famous poet’s door; he’d known poets in France where he’d taught English and feasted with golden-eyed panthers. Even so, the chiselled Sassoon induced a stammer and an apology.

Owen left Craiglockhart, where he’d been treated for shell shock, late in 1917, and wrote almost immediately to the older poet of having fallen under a new sensual spell:

“Know that since mid-September, when you still regarded me as a tiresome little knocker on your door, I held you as Keats + Christ + Elijah + my Colonel + my father-confessor + Amenophis IV in profile. What's that mathematically? In effect it is this: that I love you, dispassionately, so much, so very much, dear Fellow, that the blasting little smile you wear on reading this can't hurt me in the least.”

Owen had toyed with religion as a boy and found its hatred of the flesh wanting – “I lack any touch of tenderness. I ache in soul, as my bones might ache after a night spent on a cold, stone floor”.

Instead, he turned now to his own sensual nature as a man and the growing recognition of his attraction to men and was not disappointed. According to Dominic Hibberd, the treatment Owen received at Craiglockhart from the doctor assigned to his case, Arthur Brock, included encouragement to explore his inner-most fears and fantasies through verse. Owen obliged with several explicit poems, set in London – ‘Lines to a Beauty Seen in Limehouse’, ‘Shadwell Stair’ – and on the Western Front. In ‘Fragment’ the tumble of hot chimes of 1890s Decadence hides a real death, a soldier on the battle field, his life fading before Owen’s eyes:

I saw his round mouth’s crimson deepen as it fell,

Like a Sun, in his last deep hour;

Watched the magnificent recession of farewell,

Clouding, half gleam, half glower,

And a last splendour burn the heavens of his cheek.

And in his eyes

The cold stars lighting, very old and bleak,

In different skies.

– Wilfred Owen, Fragment

This may seem a long furlong from the war poetry more readily associated with Owen. Yet ‘Strange Meeting’ ends with the dead German soldier offering to share his bed with the poet, and an early draft of ‘Disabled’, another of his famously anti-war poems, had a stanza describing the particular charms of the young soldier, already a “god in kilts”, before he lost his legs. The lines were dropped perhaps because they spoke too much of homoerotic glamour:

Ah! He was handsome when he used to stand

Each evening by the curb or by the quays.

His old soft cap slung half-way down his ear;

Proud of his neck, scarfed with a sunburn band,

And of his curl, and all his reckless gear,

Down to the gloves of sun-brown on his hand.

– Wilfred Owen, Disabled

Men provided the subject for his verse, war the opportunity, and the meeting with Sassoon the possibility of adapting his old style to the new verse championed by poets like Rupert Brooke and John Masefield, colloquial, modern, terse, and revealed by Sorley as masterful in dealing with war.

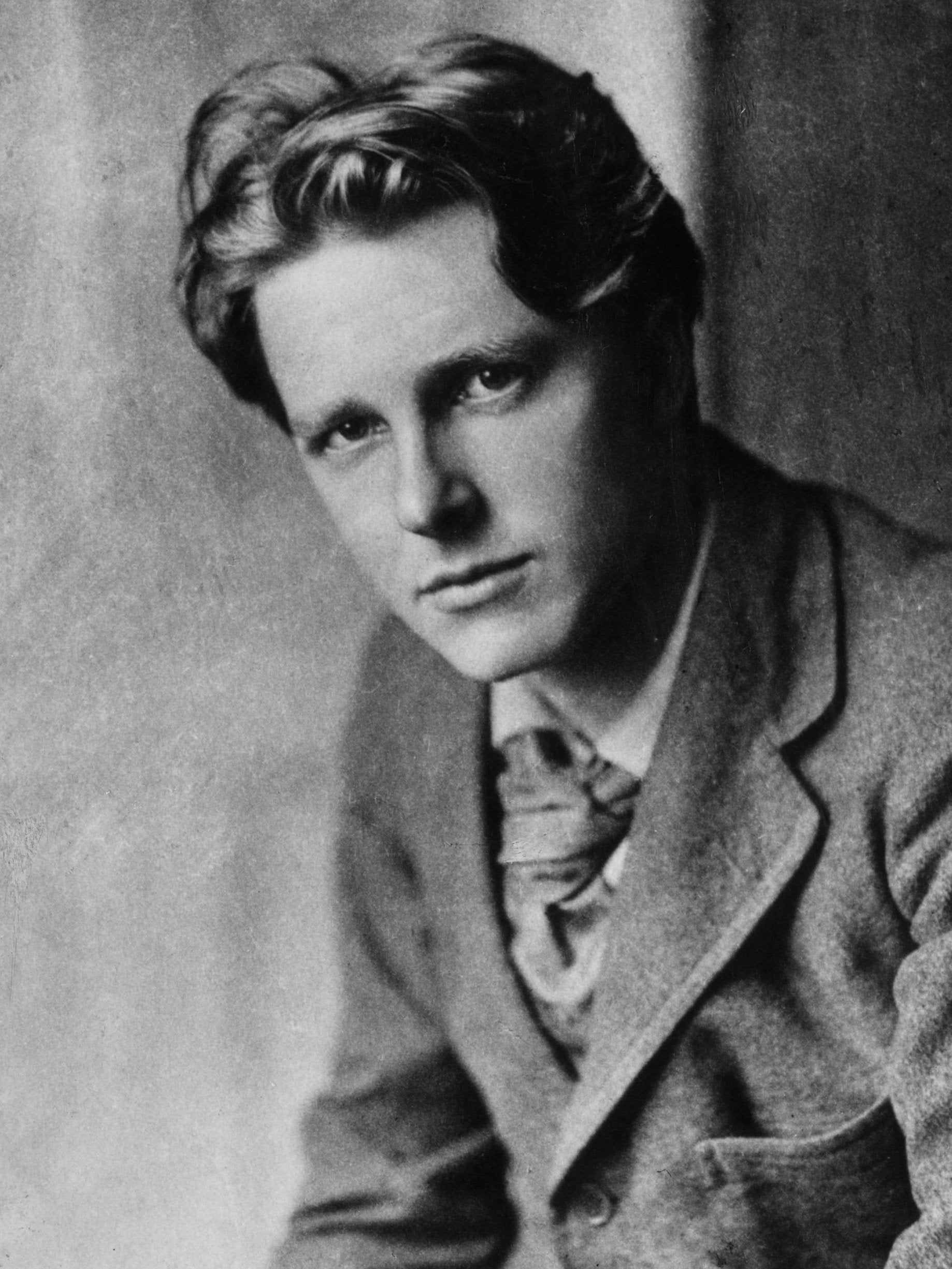

And what about Rupert Brooke? For all his supposed prowess with women, he was always susceptible to male beauty, writing from a training camp in 1914, “occasionally I’m faintly shaken by a suspicion that I might find incredible beauty in the washing place, with rows of naked, superb men bathing in a September sun… if only I were sensitive. But I’m not. I’m a warrior. So I think of nothing and go to bed,'' the last note of defiance betraying the extent to which Brooke was kidding himself.

We kissed very little…face to face. And I only rarely handled his penis. Mine he touched once with his fingers: and that made me shiver so much I think he was frightened

But then, no one at the time had written quite as explicitly about sex as Brooke did:

“We stirred and pressed. The tides seemed to wax … At the right moment I, as planned, said ‘Come into my room, it’s better there…’ I suppose he knew what I meant. Anyhow he followed me. In that larger bed it was cold; we clung together. Intentions became plain: but still nothing was said. I broke away a second, as the dance began, to slip my pyjamas. His was the woman’s part throughout. I had to make him take his off – do it for him. There it was purely body to body – my first, you know!

I was still a little frightened of his, at any too sudden step, bolting; and he, I suppose, was shy. We kissed very little…face to face. And I only rarely handled his penis. Mine he touched once with his fingers: and that made me shiver so much I think he was frightened. But with alternate stirrings, and still pressure, we mounted. My right hand got hold of the left half of his bottom, clutched it, and pressed his body into me. The smell of sweat began to be noticeable. At length we took to rolling to and fro over each other, in the excitement… the waves grew more terrific: my control of the situation was over; I treated him with the utmost violence, to which he more quietly, but incessantly, responded. Half under him and half over, I came off. I think he came off at the same time, but of that I have never been sure. A silent moment: and then he slipped away to his room, carrying his pyjamas. We wished each other ‘Good-night’…”

The letter was written in 1912 to James Strachey, brother of Lytton, but the encounter it narrates with an old lover, Denham Russell-Smith, was three years earlier. The reason for sending it becomes clearer in a sort of post-script:

“So you’ll understand it was – not with a shock, for I’m far too dead for that, but with a sort of dreary wonder and dizzy discomfort – that I heard Mr Benians inform me, after we’d greeted, that Denham died at one o’clock on Wednesday morning, just 24 hours ago now.”

Brooke’s confession is a masterpiece of telling, incorrigibly frank, but all the more fascinating for its almost forensic detachment and cool recollection – “there was a dreadful mess on the bed. I wiped it as clear as I could, and left the place exposed in the air, to dry” – a prose poem of desire and imperfect fulfilment that could never really free itself from the thought that this pagan lovemaking was somehow elegiac before the fact. There’s also a dismal irony in the fact that Denham Russell-Smith died of sepsis, just as Brooke would do.

Within three years, and long before Sorley’s name was common currency, Brooke was the war’s pinup, Saint Sebastian in khaki. His famous beauty undiminished by cropped hair and military tailoring, his tremendous popularity at home and at the front – letters from the time quote and misquote the war sonnets from his final publication, 1914 and Other Poems, without any sense of irony – are what have made him so hated by critics and biographers ever since.

It’s his last poetical fragments, however, written on the ship that was taking him to the Dardanelles, which show the trajectory he was following by spring 1915. Perhaps already feverish from the infection that would kill him and feeling more than a little Byronic in the seas off Byron’s beloved Greece, like a revenant, he wanders about the deck in the night air, peering in at his comrades at windows and doorways, men he’d known for years, men he’d loved, and who’d loved him, joined up with him on this last great adventure:

I would have thought of them –

Heedless, within a week of battle – in pity,

Pride in their strength and in the weight and firmness

And link’d beauty of bodies, and pity that

The gay machine of splendour ’ld soon be broken,

Thought little of, pashed, scattered…

It’s a disconsolate distance from the surety of ‘The Soldier’; had he lived, Brooke’s attitude towards the war and his poetical responses might have dwelt more on the death of lovers and comrades and less on his own fatal attraction. Even in his lucidity, though, Brooke still cannot help but see his comrades as schoolboys engaged in some preternatural rugby match to the death. Then the erotic possibilities of such a match, the “linked beauty of bodies”, dissolve into solipsism:

Only, always,

I could but see them – against the lamplight – pass

Like coloured shadows, thinner than filmy glass,

Slight bubbles, fainter than the wave’s faint light,

That broke to phosphorus out in the night,

Perishing things and strange ghosts – soon to die

To other ghosts – this one, or that, or I.

– Rupert Brooke, Fragment

There were a few poetic precedents for the love of the doomed young soldier: Byron’s ‘Love and Death’, Walt Whitman’s ‘Drum Beats’. Peter Parker has shown how A E Housman’s 1896 collection A Shropshire Lad, spoke to First World War soldiers, dear for all its ruminations of going to war, fragile youth, the rural idyll for which even town-born Tommies tore up northern France, and, without doubt for some, the sense of doom of being an outsider. The book was bloodied and muddied and swapped between soldiers and even the battlefield dead, who had no use for it any more, “because the essential business of poetry”, wrote Housman, “is to harmonise the sadness of the universe”.

The poet who understood this most, because he too groped through life under a blanket of sadness, was Ivor Gurney, a poet of the countryside transplanted to the city and then to the hell of total warfare. Gurney remained a private soldier throughout the war. He stayed close to his roots, inspired by snatches of moonlight through trees and the wind on the plains of Picardy, which so reminded him of the Severn valley.

Potentially one of the finest composers of his generation, he is a sort of combatant Housman: wistful, tragic, thwarted. Arthur Benjamin, a friend from his time at the Royal College of Music, was convinced Gurney was homosexual, but didn’t necessarily know it or confess it to himself.

Gurney’s friendships with men had always been deep and intense. Will Harvey, who met Gurney at school in Gloucester, became the object of some passionate love poetry, including an early rhapsodic sunset walk, remembered later in a supply line trench in France:

The elms with arms of love wrapped us in shade

Who watched the ecstatic West with one desire,

One soul unrapt: and still another fire

Consumed us, and our great joy yet greater made…

– Ivor Gurney, After-Glow

At the distance of 100 years, the need for the lover’s physical presence, rendered remotely and, appropriately for the unhappy poet, metaphysically, seems coy, just like Sassoon’s paganism and Owen’s decadent blood imagery, but by combining both, Gurney managed to write the greatest love poem of the war, ‘To His Love’, the very explicitness of its title enough to cause eyebrows to raise under any other circumstances. Perhaps written in the mistaken belief that Will Harvey was dead, it begins conventionally enough lamenting the loss of a planned future together:

He's gone, and all our plans

Are useless indeed.

We’ll walk no more on Cotswold

Where the sheep feed

Quietly and take no heed.

Soon and predictably he fixates on the lover’s body, contrasting the past with the present, and the elemental physical beauty of the young man with a young man’s strength:

His body that was so quick

Is not as you

Knew it, on Severn river

Under the blue

Driving our small boat through.

You would not know him now…

But still he died

Nobly, so cover him over

With violets of pride

Purple from Severn side.

The Shakespearean flower imagery maintains the illusion of a sort of post-classical pastoral, a modern Georgic, before the final stanza’s truth, delivered with brutal realism, shows how war intrudes with dreadful urgency:

Cover him, cover him soon!

And with thick-set

Masses of memoried flowers –

Hide that red wet

Thing I must somehow forget.

– Ivor Gurney, To His Love

* * *

“The machine guns are the most terrifying sound,” wrote Gurney in the summer of 1916, “like an awful pack of hell hounds at one’s back.” It was the summer of the Somme, the gruelling, blistering, blasting murder of a battle that seemed to last for eternity. Gurney’s Gloucestershires did their part. He was a signaller by now in a forward bay of the frontline with shells sailing over and trench mortars crumping, and the high vibrato of machine gun fire everywhere:

“It left me exulted and exulting… I am tired of this war, it bores me; but I would not willingly give up such a memory of such a time.”

“War’s damned interesting,” Gurney told a friend back in London. “It would be hard indeed to be deprived of all this artist’s material now.” He often casts an artist’s perspective on to his ruminations on trench life and army discipline, but he’s also clear eyed about the potential consequences of all this, “it is not hard for me to die, but a thing sometimes unbearable to leave this life”.

As the slaughter of the Somme ground on, Sassoon was developing his own fatalistic streak, as if anything – even death in battle – would be better than the life he’d previously led. “I want a genuine taste of the horrors,” he wrote in consonance with Gurney’s thoughts:

“…and then – peace. I don’t want to go back to the old inane life which always seemed like a prison. I want freedom, not comfort. I have seen beauty in life, in men and things; but I can never be a great poet, or a great lover.”

David Thomas was dead. Others he loved, Bobbie Hanmer, O’Brien, and Gibson (the latter two whose first names are lost to the mists of time) would die also, while nine months earlier, his younger brother Hamo had been buried at sea, after a bullet wound from a Turkish sniper at Gallipoli turned septic. No grave for him.

At the beginning of the war Sassoon had confessed his feelings for other men to Hamo – Hamo, the motor-cycle-riding scruffy-haired coeval of Rupert Brooke’s at Cambridge who’d always ribbed Siegfried’s fastidiousness and dandyism. “I’m the same,” he’d calmly replied with a smile, and they had, perhaps for the first time, shared a moment of collusion against the world.

But Hamo and ‘Tommy’ were gone, and Sassoon often contemplated his own role, heroic for sure, falling in some Homeric glory: “I ask that the price be required of me,” he told his diary rather grandly. “I must pay my debt. Hamo went. I must follow.”

Under the influence of Graves’s everyday satirical eye (and, indirectly, Sorley’s no-nonsense approach to the war), Sassoon would transform his own poetical decadence into colloquial language and sharp, bitter satire. He would become angry in war conduct as well as poetically, murderously sliding a metaphorical bayonet (Sister Steel in the poem, ‘The Kiss’) into the bodies of German foes he thought guilty of ‘Tommy’s’ death:

Sweet sister, grant your soldier this

That in good fury he may feel

The body where he sets his heel

Quail from your downward darting kiss.

– Siegfried Sassoon, The Kiss

Even before the war Owen had played with a kind of bloody Eros, pathetic lines bathed in Wildean decadence and French symbolism, but the actual sights and sounds and smells of young men dying gave this imagery a visceral immediacy and anti-pathos once he’d reached the front in 1917. In his turn, he composed in 1918 ‘Arms and the Boy’, fetishising a soldier lad’s fascination with weapons:

Let the boy try along this bayonet-blade

How cold steel is, and keen with hunger of blood;

Blue with all malice, like a madman’s flash;

And thinly drawn with famishing for flesh.

Lend him to stroke these blind, blunt bullet-leads

Which long to nuzzle in the hearts of lads,

Or give him cartridges of fine zinc teeth,

Sharp with the sharpness of grief and death.

Through this Caravaggesque tangle of knowingness and dangerous toys, Owen’s attraction towards the youth grows, the bestiality of the previous two stanzas no longer the sole agent of erotic tension:

For his teeth seem for laughing round an apple.

There lurk no claws behind his fingers supple;

And God will grow no talons at his heels,

Nor antlers through the thickness of his curls.

– Wilfred Owen, Arms and the Boy

Where Sassoon lusts for blood, Owen is not so sure, the disjunction between the feral imagery and the boy’s innocence marked by his use of pararhyme, a technique he claimed to have invented, throughout.

Critics subsequently have tended to overlook the value of Brooke’s war poetry to combatants and non-combatants – the faint hope it offered, something to cling to when the ground seems to give way beneath

Perhaps the poet most in love with death was Brooke. Hostilities offered escape from the mire he’d found himself in – of men and women he couldn’t and wouldn’t love and the crisis that had driven him half way across the world and back, still unresolved. Brooke didn’t know what he was until he was a soldier and then he’d be the idea of a soldier, lover, glory seeker, martyr combined:

Oh! We, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there’s no ill, no grief, but sleep and mending,

Naught broken save this body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.

– Rupert Brooke, Peace

He saw horror at Antwerp as the Belgian army retreated and the people there were slaughtered by a German bombardment:

“The eye grows clearer and the heart. But it’s a bloody thing, half the youth of Europe, blown through pain to nothingness, in the incessant mechanical slaughter of these modern battles. I can only marvel at human endurance.”

But sailing to the Dardanelles he was a child-like hero once again – “I suddenly realise that the ambition of my life has been… to go on a military expedition against Constantinople” – and even sun stroke from an excursion to the pyramids in Egypt didn’t seem to dim his charm. “He looked extraordinarily handsome,” wrote the expedition commander, Sir Ian Hamilton, to Winston Churchill “… quite a knightly presence stretched out there on the sand with the only world that counts at his feet.”

It was off Skyros, Achilles’ isle where the hero had been hidden by his mother to keep him from the Trojan War and an early death, that Brooke was stretchered into a small boat and rowed to a hospital ship, suffering from sepsis, probably caused by an infected mosquito bite.

He opened his eyes feebly for the last time. “Hello” he said to Denis Browne, his oldest and dearest friend who, like Patroclus to Brooke’s Achilles, had followed him into the same regiment and the same theatre of war and would soon follow him through the “unknown door”. Browne and his friends would bury the poet on Skyros under torchlight that night, writing “[n]o one could have wished for a quieter or a calmer end than in that lovely bay, shielded by the mountains and fragrant with sage and thyme.”

Brooke’s sonnets were in the possession of soldiers and civilians alike throughout the conflict, a gentle, sombre kind of war poetry – “no passion for glory here,” wrote a TLS critic, “no bitterness, no gloom, only a happy clear-sighted all surrendering love”.

Critics subsequently have tended to overlook the value of Brooke’s war poetry to combatants and non-combatants – the faint hope it offered, something to cling to when the ground seems to give way beneath. Like Housman, Brooke acknowledged the presence of death and the richness of the soil for which a soldier died, a pungent, deep soil, steeped in the “red sweet wine of youth”, an almost ineffable beauty now an even greater aphrodisiac:

War knows no power. Safe shall be my going,

Secretly armed against all death’s endeavour;

Safe though all safety’s lost; safe where men fall;

And if these poor limbs die, safest of all.

– Rupert Brooke, Safety

If Brooke didn’t exactly die for his men, that soon became the sense of his sacrifice. Sorley, who hadn’t liked Brooke’s war poetry, couldn’t help becoming a second Brooke in France, younger, fresher, less complicated, but more of a mind with the boy officers who followed him to the Front:

Victor and vanquished are a-one in death:

Coward and brave: friend, foe. Ghosts do not say

‘Come, what was your record when you drew breath?’

But a big blot has hid each yesterday

So poor, so manifestly incomplete.

And your bright Promise, withered long and sped,

Is touched, stirs, rises, opens and grows sweet

And blossoms and is you, when you are dead.

– Charles Hamilton Sorley, Such, Such is Death

In the early autumn of 1916, at a weekend in Garsington Manor, the country house of Lady Ottoline Morrel, staffed with Bloomsbury Hectors and Conscientious Andromaches, with music and wine and walks through the garden and a turbaned and burdened Ottoline gently pouring Bertrand Russell in his ear, Sassoon began to falter in his determination to be a soldier for the sake of soldiers. Hadn’t his men suffered enough? Hadn’t his old mentor, Edward Carpenter, written in response to the slaughter on the Somme, “[t]he rapid and enormous growth of scientific invention makes it obvious that Violence 10 times more potent and sinister than that which we are witnessing to-day may very shortly be available for our use – or abuse – in War”?

What followed, A Soldier’s Declaration in July 1917, a distillation of Bloomsbury anti-war rhetoric, and Sassoon’s refusal to report for duty, may show the martyr seeking martyrdom, if not from the Hun then from the War Office, but it was uncharacteristic of the idealist warrior Sassoon had become and, after weeks in the hospital at Craiglockhart, he recanted and chose to return to the front and the men he, guiltily now, had left behind:

The darkness tells how vainly I have striven

To free them from the pit where they must dwell

In outcast gloom convulsed and jagged and riven

By grappling guns. Love drove me to rebel,

Love drives me back to grope with them through hell;

And in their tortured eyes I stand forgiven.

– Siegfried Sassoon, Banishment

Even Owen, now completely under the spell of Sassoon and newly militarised, wrote: “I hate washy pacifists as temperamentally as I hate whiskied prussianists. Therefore, I feel I must first get some reputation of gallantry before I could successfully and usefully declare my principles.”

Sassoon and other acquaintances such as Charles Scott Moncrieff already had Military Crosses, the common badge of bravery. If he were to be an honest war poet Owen needed “some reputation of gallantry”, hence his otherwise suicidal decision to reapply for active service. In poetry he describes the physical regime required to be fit – oddly reminiscent of Charles Sorley – and imagines lovers he must turn away until he has achieved this goal, to be a soldier worthy of the name of poet:

Not this week nor this month dare I lie down

In languor under lime trees or smooth smile.

Love must not kiss my face pale that is brown….

Cold winds encountered on the racing Down

Shall thrill my heated bareness; but awhile

None else may meet me till I wear my crown.

– Wilfred Owen, Training

* * *

On the back of the folio that contained one of his more difficult to place poems, ‘Has Your Soul Sipped’, Owen jotted down “Marlboro’ and Other Poems / Chas. Sorely [sic]”. A note to self to read, or a note to the reader that the poem Owen had written in some way related to the dead poet of 1915? ‘Has Your Soul’ is an odd combination of pagan decadence and battlefield realism, or rather it trips uneasily from one to the other.

It’s a giddy ride, a litany of what the poet has witnessed of “strange sweetness” finishing with the strangest of all, a smile on a dead boy’s face, a boy in his company, or Sorley, or someone else. It’s written in pararhyme, which suggests a relatively late date, but it feels like a shift towards that later understanding, the earlier stanzas all rubies and moonrise, the latter adopting the sort of clear caustic diction – “life tide”, “bitter blood”, “death smell” – that Owen would make his own in 1918. Perhaps it was written in two distinct intervals. Perhaps it’s a showing of how his reading of Sorley had changed his ways.

Artistically then, Owen and his poetry were at a crossroads. In a few months from the summer of 1917 to the spring of 1918 he would write the poems that defined his oeuvre and the poetry of the First World War in general. But he would not become the prophet of male love. That was left to others. In his diary, Sassoon had also written “[w]hen war ends I’ll be at the crossroads,” and by mid-1918 he’d reached it, finally invalided out of active service, and had made his choice: to pursue truth, to be true to himself, his nature.

Soon after, he predicted that he would one day write something that would make the callous old world sit up and take notice:

“It is to be one of the stepping-stones across the raging (or lethargic) river of intolerance which divides creatures of my temperament from a free and unsecretive existence among their fellow men. A mere self-revelation, however spontaneous and clearly-expressed, can never achieve as much as – well, imagine another Madame Bovary dealing with sexual inversion, a book that the world must recognise and learn to understand.”

It’s a pity Sassoon never wrote his Madame Bovary, but he did, at least, abandon his much vaunted celibacy within a month of Armistice Day, tupping like a ram with a young artist named Gabriel Atkin – “Siegfried is the most amazing gorgeous person in the universe” – and writing poetry that was both yearning for fulfilment and shaded with warning for any lover who thought of taking him on:

Oh yes, I know the way to heaven was easy.

We found the little kingdom of our passion

That all can share who walk the road of lovers.

In wild and secret happiness we stumbled;

And gods and demons clamoured in our senses.

But I’ve grown thoughtful now. And you have lost

Your early-morning freshness of surprise

At being so utterly mine: you’ve learned to fear

The gloomy, stricken places in my soul,

And the occasional ghosts that haunt my gaze.

– Siegfried Sassoon, The Imperfect Lover

The world was also full of ghosts – “I’ve still got my terrible way to tread before I’m free to sleep with Rupert Brooke and Sorley and all the nameless poets of the war” – and the dead loomed large in dreams. From his asylum room Ivor Gurney looked back and wondered about the fates of the men he’d served with, concluding that each inhabited “Strange Hells”. Gassed near the Ypres salient in September 1917, Gurney’s war was over then but his struggle to live beyond the trenches only just begun. “O to be at the Front, enduring in company with splendid people of the Gloucesters,” he wrote feebly from an Army hospital where he’d been diagnosed with “deferred shell-shock”. The ennui of a “Blighty” would eventually spill into the strange poetry he wrote in various asylums after 1922. Was it the war that tripped his mind, or was it forbidden desire in a hostile peace? In fragments of poetry he talks elliptically of his “crime” and police harassment, but these are only vague reflections.

Can you photograph the crimson hot iron as it cools from the smelting? That is what Jones’ blood looked like and felt like

Sassoon’s money might have bought him a place in the new post-war society. Gurney’s madness might have insulated him from the indifference. Graves’ arrogance meant he didn’t care. The reasons why Sassoon returned to the trenches in 1918, the reasons why Gurney wished he’d never left and the reasons why Wilfred Owen struggled bravely on in the last month of the war may have been complex: but always present, sometimes in palpable human form, oftentimes just a phantom in the woods or on the battlefield, was the love they felt for the young men they fought alongside, a love they were prompted to celebrate in song. Writing to his mother in early October 1918, Owen rehearsed, as much for himself as for her, his motivation for returning to the fight:

“I came out in order to help these boys – directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a pleader can. I have done the first.”

The lofty tone of burden, the detached observer of men’s suffering, the leader and pleader cannot help breaking down in the next moment into cryptic poetic language, the old 1890s Decadents lending a hand when his new words fail, as Owen remembers one young man who’d been badly wounded (some believe killed) in a recent attack: “Of whose blood lies yet crimson on my shoulder where his head was – and where so lately yours was – I must not now write.”

Owen’s servant Private Jones had been shot in the head in an attack on the German lines. It was Jones’ job to protect his officer in battle, but now Owen lay with him on a slight incline as the war raged on, “the boy by my side, shot through the head, lay on top of me, soaking my shoulder, for half an hour,” he told Sassoon

“Can you photograph the crimson hot iron as it cools from the smelting? That is what Jones’ blood looked like and felt like. My senses are charred. I shall feel again as soon as I dare, but now I must not.”

Because now he must leave Jones for the stretcher bearers and, soaked in his blood, in battle rage, charge the German positions, seizing a machine gun post and driving German bodies from the field or their souls from the earth. Now he is a soldier, unfeeling, unflinching. Now he will be recommended for a Military Cross. But he would never know, because a little over a month later and a week before the Armistice, he was shot dead crossing a dank canal.

On arriving at the Western Front Ivor Gurney described coming across a group of Welsh soldiers in a dugout, “four of the most delightful young men I could have met anywhere”. They talk about everything, he says, from Welsh folksong to Oscar Wilde, while the war cracks and whirrs and the memory of lost friends from a recent strafe brightens the candle-lit scene. “In the face of their grief I sat there… and gave them all my love, for their tenderness, their steadfastness and kindness to raw fighters.” But then his attention is drawn to just one of the young men a short while later:

“Once we were standing outside our dugout cleaning mess tins, when a cuckoo sounded its call from the shattered wood at the back… This Welshman turned to me passionately, ‘Listen to that damned bird,’ he said. ‘All through that bombardment in the pauses I could hear that infernal silly “Cuckoo, Cuckoo” sounding while Owen was lying in my arms covered with blood. How shall I ever listen again…!’ He broke off, and I became aware of shame at the unholy joy that filled my artist’s mind. And what a fine thin keen face he had, and what a voice…”

In detail is grandeur. The cuckoo’s call, the herald of spring, is the harbinger of death and a germ of something in Gurney’s artist’s mind. Small things stand in for the panorama, the individual for the millions, a ghost for the dead.

Those few years of blood and love in war were the branding that marked these poets for good; and the feelings that spilled so sheer from them in turn changed poetry in English and blighted war forever. We have little time before the blood slows and recollection wanes. A hundred years ago is a long interval and yet, as remembrance comes to an end, it isn’t so much the horror of war, the details of blown-off limbs, bullet wounds and filthy mud, as that intense love, that intenser sacrifice, which ought to, and which does, still speak clearly.

In his second book of war poetry, Counter-Attack and Other Poems, published just as he returned to the Front in May 1918, Sassoon was at his fieriest and most biting. Poems such as ‘Does it Matter?’, ‘Suicide in the Trenches’, ‘To Any Dead Officer’ have come to define the detached cynical attitude of soldiers to the war they fought in.

But then Sassoon does something surprising at the end of his book. Two years after David Thomas had been killed, he remembers their rides together and finishes his war with a gentle poem to lost love among Kentish ways, ‘Together’, almost in defiance of the times.

Splashing along the boggy woods all day,

And over brambled hedge and holding clay,

I shall not think of him:

But when the watery fields grow brown and dim,

And hounds have lost their fox, and horses tire,

I know that he’ll be with me on my way

Home through the darkness to the evening fire.

He’s jumped each stile along the glistening lanes;

His hand will be upon the mud-soaked reins;

Hearing the saddle creak,

He’ll wonder if the frost will come next week.

I shall forget him in the morning light;

And while we gallop on he will not speak:

But at the stable-door he’ll say good-night.

– Siegfried Sasoon, Together

------------

All quotations from Siegfried Sassoon are copyright Siegfried Sassoon and reproduced by kind permission of the estate of George Sassoon. Poetry quotations from Robert Graves, War Poems, C Mundye ed, Poetry Wales Press 2016; copyright Carcanet Press Limited

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments