Princess Diana: How the tabloid press treated her in the run up to her death

On the eve of the 20th anniversary of Diana’s death, David Barnett looks at how the ‘People’s Princess’ became the ‘most hunted person of the modern age’ and asks when will those who overstep the mark learn their lesson

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 6 September 1997, Charles Spencer – the 9th Earl Spencer and younger brother to Diana – delivered a blistering eulogy on the occasion of the funeral of his sister. His words touched a nerve all across the world as they spoke of how Diana’s “particular brand of magic” needed no royal title to legitimise it.

But he also had strong words for the media, particularly the tabloid press, and their treatment of Diana in what no-one could have guessed were her final days.

He spoke of how Diana, in the year after her divorce from Prince Charles, had “talked endlessly” of leaving Britain, “mainly because of the treatment that she received at the hands of the newspapers. I don't think she ever understood why her genuinely good intentions were sneered at by the media, why there appeared to be a permanent quest on their behalf to bring her down. It is baffling”.

Spencer struck a poetic note when he said: “It is a point to remember that of all the ironies about Diana, perhaps the greatest was this – a girl given the name of the ancient goddess of hunting was, in the end, the most hunted person of the modern age.”

Looking back across 20 years it is sometimes easy to forget that Diana was not some remote royal whose death was a sudden, surprising thing that came out of nowhere. In the months before, she had appeared with almost exhausting regularity on the front pages of the newspapers, and indeed had a profile that today we rarely see among the royals.

There was an obsession with Diana, her every move was checked and documented and filed. The tabloids led on the most spurious stories for days on end. For a newspaper editor, those must have been the glory days. Where today the red-tops busy themselves with the minutiae of the movements – one, suspects, carefully choreographed by legions of PR executives – of instantly forgettable reality TV stars, back then there was an actual, honest-to-God princess providing the headlines.

Indeed, conspiracy theories notwithstanding, it was while being pursued by paparazzi that Diana, Dodi Fayed – the son of the then owner of Harrods, Mohammed al-Fayed – with whom she was in a relationship, and driver Henri Paul all died during in the 31 August car crash in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel in Paris.

The hunter, it seemed, had not only become the hunted, but ultimately the kill.

The media hung its collective head in shame, even those who sought in the days and weeks after Diana's death to distance themselves from the tabloids, while even the tabloids stepped back for a while from lining the pockets of the paparazzi who had taken on almost demonic status for their relentless pursuit of the “People’s Princess”.

Since well before Diana’s death, moves had been in place to protect her sons, Princes William and Harry, from the intense press spotlight that had been shone not just on her but on all of the Royal Family. It was as early as 1995 that a “gentlemen’s” agreement between Fleet Street and Buckingham Palace was shaken on, timed to coincide with William going to Eton, aged 13.

Charles himself had been the subject of intense press scrutiny as a student, and both he and Diana wanted to spare their sons similar intrusion. Charles Spencer drove the message home in his eulogy when he said: “She would want us today to pledge ourselves to protecting her beloved boys William and Harry from a similar fate and I do this here Diana on your behalf. We will not allow them to suffer the anguish that used regularly to drive you to tearful despair.”

The agreement between the royals and the press was renewed in the year 2000, and save for a couple of missteps by the nationals – in 2003, The Mail on Sunday published a series of photographs snatched of William going about his business in the Scottish university town of St Andrews – the feeding frenzy of the press that we saw prior to the mid-Nineties has rarely been repeated.

Of course, in the years after Diana’s death, there were mutterings that the press attention on her was not just a one-way street. In fact, there were claims that Diana not only actively courted the press, but also manipulated them.

Tina Brown, the former Vanity Fair editor who wrote the controversial 2007 book Diana Chronicles, claimed that Diana would often tip off the press to her whereabouts and nurtured close relationships with some members of the media.

Speaking on a Canadian news show a decade ago, Brown said that Diana “did want some privacy, but at the same time she couldn't resist giving them the images they wanted and one of the pictures she had allegedly tipped them off about was that she was on a boat with Dodi and said, ‘Take this picture of me on the boat’.”

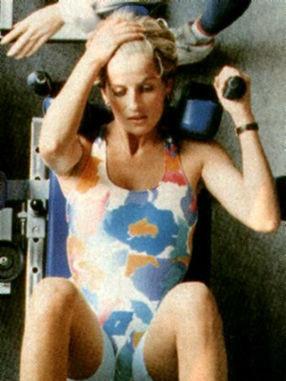

There were those who agreed, even when Diana was still alive. One infamous case took place in 1993, when Diana was photographed – with a concealed camera – working out at a London gym. The pictures made their way on to the front pages of the tabloids, and the gym owner who took them was unrepentant.

“What was Princess Diana doing there in the first place if she didn't want to be seen?” he said on TV. “How many women do you know who work out in full make-up? How many do you know who supposedly work out hard and then don't sweat?”

All of which suggesting, of course, that Diana knew full well that she was likely to be photographed, perhaps even wanted to be photographed, and was determined to look her very best for it.

There has perhaps long been an attitude that those who live by the sword can die by the sword, in publicity terms. There is a sometimes phoney war conducted by celebrities and the press, where the front lines are obscured by the fog of public relations. We pity the female starlet snapped looking not her best and overweight while exercising in the park; then we wonder at the coincidence of a fitness video announced just a heartbeat later. It’s perhaps no wonder that the insatiable desire for celeb news on the part of the tabloids and the insatiable desire for publicity on the part of the PR machine will often intersect, and maybe rack up collateral damage of those who have a genuine desire for privacy.

Did Diana live by the sword of courting the press? She certainly died from it, whether it was self-inflicted or not. There would be few who would suggest, surely, that anything she got, she deserved. But are things any different now?

It wasn’t Diana’s death which prompted the most high-profile call for press regulation, 2011’s Leveson Inquiry, but the seeds of it were certainly sown 20 years ago. Leveson, of course, was the result of the widespread phone-hacking that took place among some national newspapers over the course of many years. But the shadow of Diana’s death did hang heavy over the probe.

Media lawyer Mark Thomson, who represented many high-profile clients in the inquiry, spoke of the “absolutely terrifying” incidents he had witnessed through videos taken by celebrities of freelance photographers pursuing stars in cars and motorbikes.

David Barr, representing the Leveson inquiry, pointed out that “lessons which might have been learnt after an inquest conducted in this very court” – referring, of course to the inquest into the death of Diana – “have not been learnt”.

Six years on from Leveson, we have two main press regulation bodies, the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso), and Impress, the latter backed by the Press Recognition Panel set up in the wake of Leveson. The man on the Clapham omnibus so beloved of Fleet Street editors of yore might have trouble working out which of them does what; the major legacy of their creation seems to be something of a cold war between the two organisations, with Ipso representing the majority of the national newspapers and Impress a mixture of regional press and online platforms.

Has it made any difference? Ultimately, the dichotomy of media consumption maintains a sense of uneasy balance between the fourth estate and the public where peace is maintained so long as just the right measure of intrusion into privacy is carried out.

The press plays as important a role as it has ever done in holding those in power to account, and if a byproduct of that is belt-and-braces detail on the lives and loves of the famous, then so be it.

It’s when the press next oversteps its mark – hacking phones, publishing photographs obtained by underhand means, or pursuing a much-loved public figure to their death – that we will properly find out if the latest watchdogs have any more teeth than their equivalents did in Diana’s day.

Then we will know, to invert Charles Spencer’s moving eulogy, whether the hunters of the tabloid press will become the hunted, and what that will mean for the two sides of the coin of press freedoms and press regulation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments