How an author set out to write about pirates – only to end up kidnapped

Michael Scott Moore had planned to write a book about Somali pirates that was pure reportage – but, as he tells Andy Martin, it became a lot more personal when they took him hostage

Most of the time writers are only sitting in front of a keyboard. The worst thing we have to worry about is repetitive strain syndrome and drinking too much coffee. But there is a heroic hardcore who are willing to put themselves in the way of harm to tell the story.

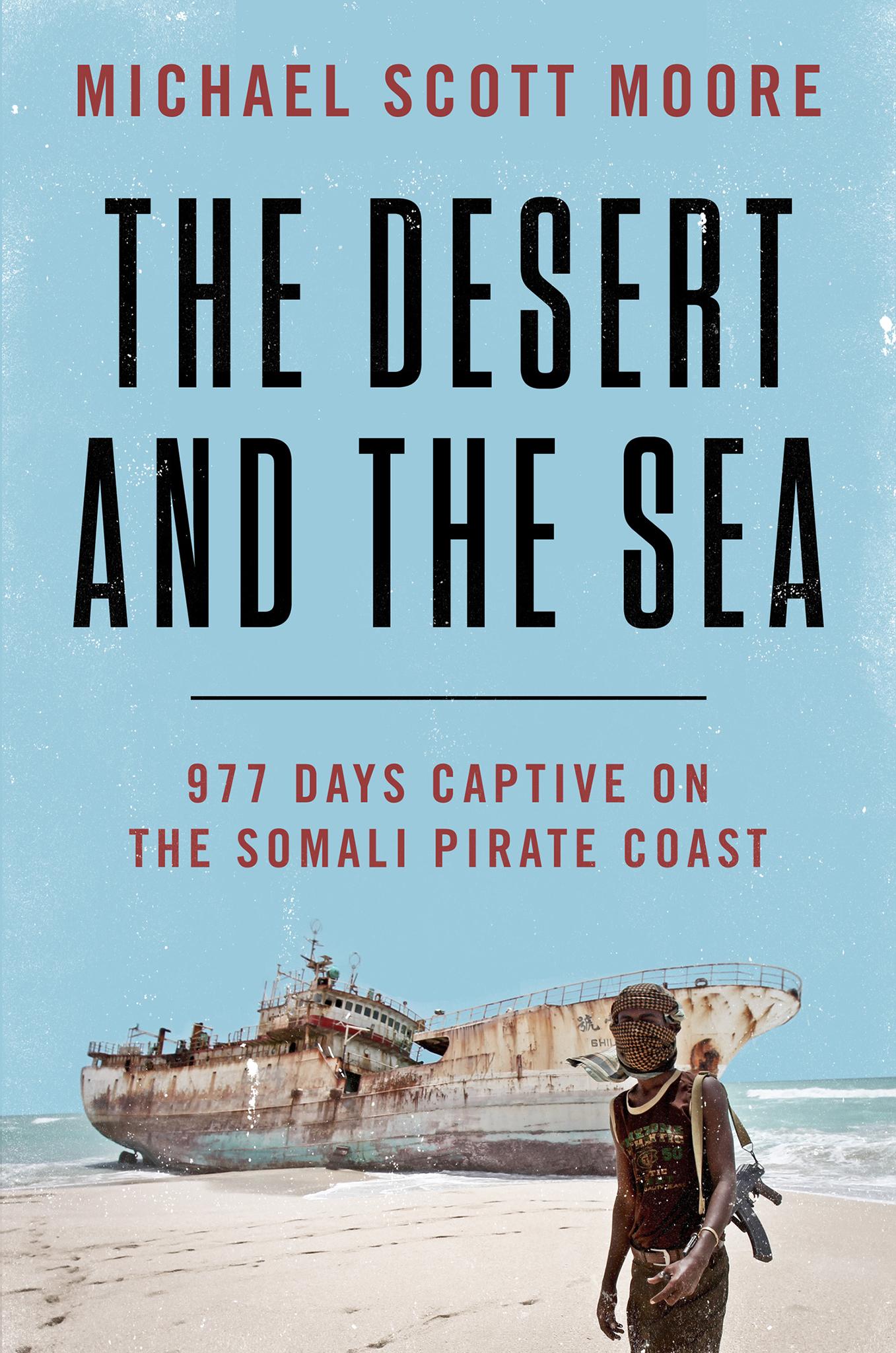

Writing about certain presidents and princes can be bad for your health. In Michael Scott Moore’s case, it was pirates. He was doing research into pirates, so like any decent reporter worth his salt he thought he should go and interview one. What happened next you can read about in his new book, The Desert and the Sea. The clue is in the subtitle: 977 Days Captive on the Somali Pirate Coast.

What image springs to mind when you think of pirates? Johnny Depp? An eye-patch? A cutlass? For me, it’s more an adjective – “swashbuckling”. Criminals of the high seas, of course, but romantic daredevils, skilled swordsmen, daring nomadic outsiders, surely. Michael Scott Moore has finally put paid to any lingering remnants of the myth by way of being kidnapped by them and held hostage for nearly three years, driven to the brink of madness, malaria and suicide by “a stupid and self-aggrandising pirate society, a suicidal culture in which gunshots rang in the street and gunmen were winners”.

Moore was a surfer – and author of Sweetness and Blood, a history of American expansionism after the Second World War, seen through the turquoise lens of surfing – who naturally felt a certain rapport with the men who make their living off the sea. And he felt that piracy was not exactly unknown in American history. “North America,” Moore writes, “had evolved from an underdeveloped haven for pirates to an antipirate world power within three generations.”

I saw him before he left for Somalia – hale and hearty – and I went to see him again recently, in a cafe in West Village, New York, several years later, after he got back, now 49, looking like a war veteran, wounded, skinnier, traumatised, but a survivor. Older and wiser. He had planned to write a book about Somali pirates that would be pure reportage, “but,” he says, “it became more personal from the moment I got kidnapped”.

When you’re held hostage your entire life up to that moment keeps replaying itself in your head. His father, Bert Moore, was an aerospace engineer and alcoholic who committed suicide when Michael was aged 12. His mother told him it was a heart attack. He only found out what really happened 30 years later when he asked for a copy of the death certificate that read: “Gunshot to left chest”. He had been kicked out of the family home in the suburbs of Los Angeles by Mrs Moore. After a year of trying to get sober he shot himself. Mother and son went to live in Redondo Beach, where he started surfing.

When his first marriage fell apart, Mike left his old southern Californian life behind and set up in Berlin. Somehow he ended up writing about pirate activities for Spiegel Online International and attended the trial of 10 pirates in Hamburg, in 2011. It was the first trial of pirates on German soil for 400 years. They had been arrested after a gun battle with Dutch commandos while trying to hijack a German ship.

“I was as full of pirate romance as the next American kid” says Moore. He knew that Pirates of the Caribbean was pure Hollywood. But still he wanted to find out what they were really like. Moore had been to the Horn of Africa before – on a counter-piracy vessel, a Turkish warship.

But in January 2012, supported by a couple of magazines and a grant from the Pulitzer Centre on Crisis Reporting, he set off again, without a warship this time. To be on the safe side he had tried to get kidnap insurance and been turned down. But he wasn’t naive. He knew he was in “a country where no one could save me if things went wrong”. He had security. “Good security”, as he describes it. The problem was that at the crucial moment they “disappeared”. They sold him out. He was paying them well, but the pirates were paying them more. And they were part of the same clan. “That particular clan was supposed to be hosting and protecting me,” he says with an ironic grin.

He interviewed a pirate called Mustaf in a flyblown restaurant in Hobyo where he had to pay $620 for lunch. He left a filmmaker colleague at the airport and was being driven back into town along “Pirate Road” when his car was stopped by a dozen men bristling with automatic weapons. He was beaten, his glasses were broken, and he was bundled into the pirate vehicle of choice, a Toyota Land Cruiser.

One of the pirates had the cheek to say to him, as if it was all his fault, “You have made a mistake.” It is a phrase that haunts him even to this day. For a long while in captivity, he felt the pirates were right about that: “I was a tall, white man hoping to make friends with pirates. Crazy.”

Being a writer meant that he was worth something. “I have seen you on the internet,” said one of his captors. “You are famous.” He denied it. Then they fished out a picture of him that had appeared in the New York Times. I had even contributed in a small way to adding to the price on his head by writing an enthusiastic review of his surfing book in that newspaper. The asking price was $20m. If only I’d slated his book it might have brought the price down by a few million. His friends soon learned he had been kidnapped but we were warned not to write anything. Every time his name was mentioned on the BBC his price went up again.

He was regularly beaten, and threatened with torture, or being handed over to al-Shabaab, but one of the worst things about being held in captivity is not having anything to read. One of the highlights of his first few months was piecing together fragments of The Gulf News which had been wrapping up samosas. Taken to a ship a mile offshore, the Naham 3 – a highjacked fishing vessel – he was given a Bible by one of his fellow hostages. A lapsed Catholic, he read it twice from cover to cover, having to squint all the while, but finding consolation in “the gritty survival ethic” of the Old Testament. He decided he was not so keen on crucifixion as such.

There were a lot of guards on the ship, and a fair few sharks in the water too. And without glasses he could barely make out where he was going. But in the end he leapt off the ship in a bid for freedom. He didn’t make it and spent the next three weeks chained up in solitary confinement. I read a story online about how he had been shot while trying to escape. This turned out to be a myth put about by the pirates themselves, with a notion of speeding up delivery of the ransom.

Around this time Moore devoutly wished he had become an astronaut – or anything – rather than a writer. As a kid, his bedroom had been decorated with astronaut wallpaper, peppered with rockets and moons and stars. Now marooned on board a very terrestrial ship, he was tormented by dreams and rumours of a rescue that never came. But there was still one option available to him. He could try and shoot his way out. It would be the heroic thing to do. But it would also be stupid. The guards had a habit of leaving their Kalashnikovs lying about. There was zero chance of getting away but he could go out in a blaze of glory and bullets, and maybe take a pirate or two down with him. “I was angry enough to pick up a Kalashnikov,” he says.

The thing that stopped him was the memory of his father’s suicide. His logic was that he didn’t want his mother to have to bear witness to both the men in her life self-destructing. His mother becomes one of the heroes of the book. German in origin, Marlis was still playing tennis and golf, and was due to have lunch at a Mexican restaurant when five men in suits (unheard of in Redondo Beach) turned up at her door. Schooled by the FBI, she had to conduct ransom negotiations herself over the phone, driving the price down from $20m to $8m, then down to $5m, and finally $1.5m. In the end she recruited a mercenary to deliver $700,000, which she managed to cobble together from different sources, friends, family and Der Spiegel.

“I’m still angry,” Michael says, “about losing more than two years of my life.” But he had to rein in his anger if he wanted to live. When he explained he needed a doctor for his broken wrist the trigger-happy guard said to him, “You mean it was broken in this operation.” He was tempted to reply, “No motherf***er, I’m in the habit of walking around Somalia with a broken wrist.” “Yes” is how he chooses – rather carefully – to phrase it.

He developed friendships with the other hostages – Chinese, Cambodian, Vietnamese, Filipinos –and he came around to liking some of the guards. But he was never tempted by Stockholm syndrome: “I went through a long period of wanting to kill them.” Notably one guy by the name of Ali.

Sometimes your reading can save your life. In Moore’s case it was Epictetus, the great stoic philosopher. Stoicism says that you can’t do a lot about your fate, but you can control your attitude towards it. Epictetus asks the question, what do you do if your servant drops your favourite vase and it smashes into a thousand pieces? Do you lash out and whip the servant, or do you say – which is what he recommends – “the vase has been restored”. Moore grits his teeth and develops a sense of humour about his predicament. “Not that I laughed every day.” When he was staring down the barrel of a gun, quite literally, he learned to sit and accept the prospect of a sudden death. “I had to train my mind for actual non-existence.”

As well as ancient Greek philosophers, a collection of Tom and Jerry cartoons definitely helps. As does news, on a short-wave radio, of the World Cup in Brazil in 2014, when Germany thrashed Brazil 7-1 in the semi-final.

There is an ironic twist in Moore’s story, when most of the people who tormented him for so long are annihilated, in a way he could never have anticipated, but which reflects what he writes about the rise of “factionalism and violent opportunism”. One further irony: when he gets free he even has one of his former captors becoming a Facebook “friend”.

Maybe he could have made it as an astronaut, but he is the most persistent and unstoppable of writers. He simply stole a pen and paper from the pirates and wrote about his experiences, like a Solzhenitsyn of the Somali gulag. But these samizdats never see the light of day. When his guards read their own names they confiscate his notebooks, again and again. Finally he realises his only way out is fiction. He sets his novel in southern California, not in Somalia. About a quixotic innocent who is kidnapped by bad guys. It was partly allegory, to remind him of what happened, but now it’s in danger of becoming his next book.

For Michael Scott Moore, writing is therapy, a way of retaining sanity. “To put painful events into a certain order, I had to find a way through it. The easiest thing was to set down what happened.”

I asked him what he missed most during his 977 days. “I’m not sure there was any one thing. Beer? Fresh fruit? Above all my family and friends. Everything about my old life, good and bad,” he said. “I was just grateful to be alive in the end.”

There is almost a note of sadness or nostalgia in his voice when he says that the traditional Somali pirate is now virtually extinct. “The business model has evolved. They’ve shifted into arms and human trafficking. Piracy has become too dangerous.”

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’, and teaches at the University of Cambridge

‘The Desert and the Sea: 977 Days Captive on the Somali Pirate Coast’, by Michael Scott Moore, is published by Harper Collins

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments