Tampon and pad shortages in lockdown means now is the time for sustainable period products

Thousands of women ran out of period products during lockdown, this means it is time we took sustainable products seriously, says Supriya Garikipati

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

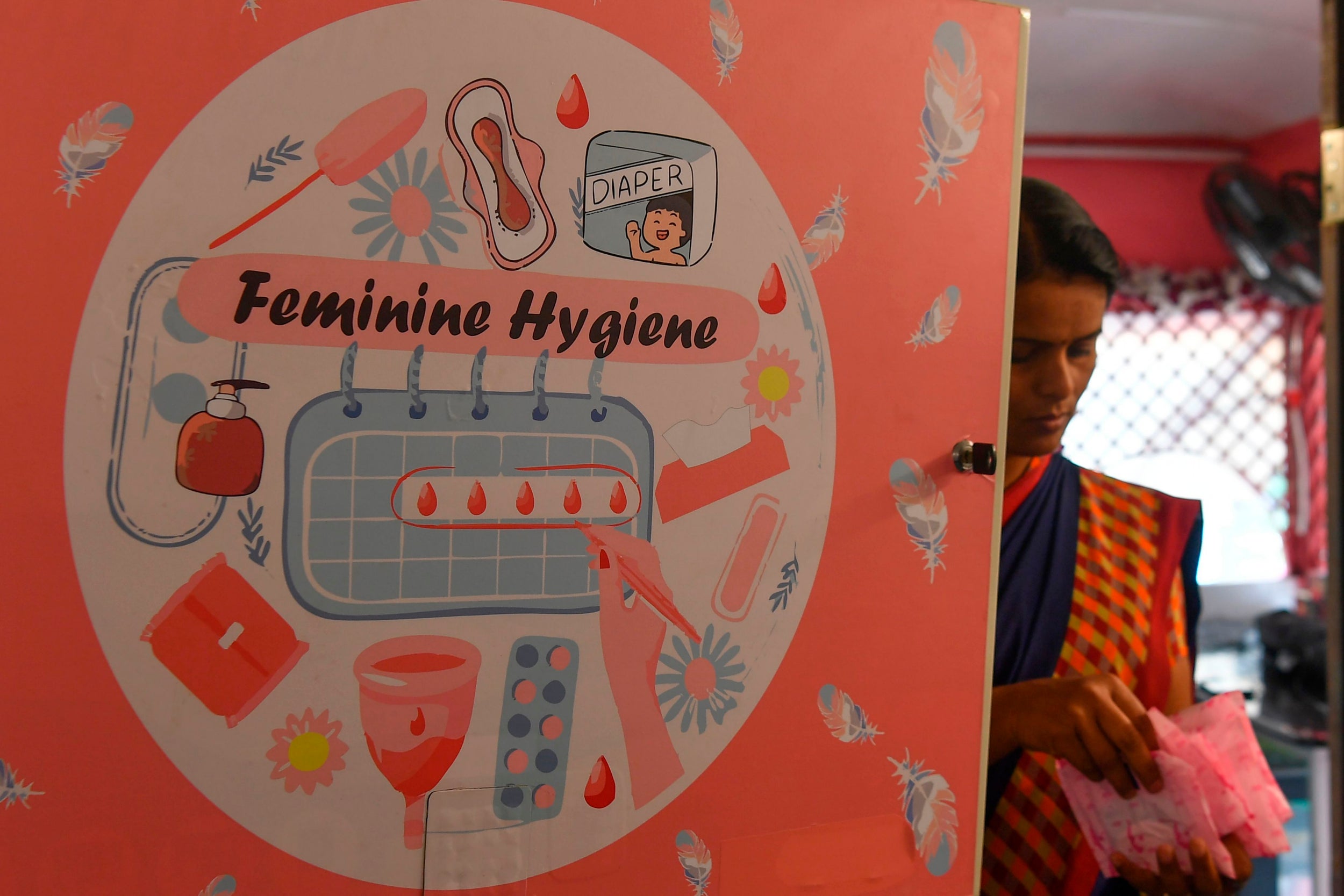

Your support makes all the difference.The coronavirus pandemic has triggered what has been described as a “sanitary pad crisis” in India. Priya, a 14-year-old schoolgirl, considers herself lucky: her parents can still afford pads. But several of her friends will have to go without. In some parts of India, schools are a critical part of the supply chain, providing a pack of pads to girls each month. With schools closed, along with other supply chain issues, as few as 15 per cent of girls had access to sanitary pads during the lockdown.

This is not the case only in India. Women in Fiji, US, UK and other parts of the world have also reported severe supply shortages and hiked up prices for disposable menstrual products.

But in India, where I have spent much of the last few years researching how women choose to manage their periods, shortages are particularly severe. The situation escalated quickly as India went into an sudden and complete lockdown on March 24. This put an immediate stop to the monthly supply of pads that millions of adolescent girls received via their schools. The production of sanitary pads also came to a screeching halt for seven days, which lead to stockouts in several locations.

Pads were reclassified as essential items eligible for supply chain operations on 30 March but even now supplies have not resumed to normal levels in many places. Safa India, an NGO I work with, is busy teaching women how to make cloth pads at home. And several large charities, like KGNMT, have started distributing reusable pad kits to vulnerable women.

Women in India mainly use disposable pads or traditional cloth to manage their periods. The past decade has seen the government campaigning hard for women to use disposable pads, putting across the message that disposable pads are the only hygienic way to manage menstruation. They did so to encourage women to transition away from the use of traditional cloth, which was seen as difficult to maintain hygienically. But little has been done to create awareness of other, cheaper, more sustainable alternatives, such as menstrual cups and reusable pads.

I set out to investigate this – to find out what Indian women know about their options to manage periods, and whether giving them more information would change their approach. I found that their knowledge about other available options to manage periods is severely lacking, and that giving women more information created more demand for sustainable products like menstrual cups and reusable pads – products that would have been impervious to the shortages many women experienced under lockdown.

Good menstrual hygiene is so much more than just access to sanitary products – water, toilets and equitable gender norms also matter – but they are essential in the management of periods and current practices are far from sustainable.

But first, how did disposable pads come to dominate the Indian market?

Disposable sanitary pads and tampons may seem indispensable today but they have been around for fewer than 100 years. Until the turn of the 20th century, women simply bled into their clothes or, where they could afford it, shaped scraps of cloth or other absorbents like bark or hay into a pad or tampon-like object.

Commercial disposable pads first made an appearance in 1921, when Kotex invented cellucotton, a super-absorbent material used as medical bandaging during the first world war. Nurses started to use it as sanitary pads, while some female athletes gravitated towards the idea of using them as tampons. These ideas stuck and the era of disposable menstrual products began. As more women joined the workforce, demand for disposables started to increase in the US and UK and by the end of the Second World War, this change in habit was fully established.

Marketing campaigns helped further this demand by leaning heavily into the idea that using disposables freed women from the “oppressive old ways”, making them “modern and efficient”. Of course, the profit incentives were considerable. Disposables locked women into a cycle of monthly purchases that would last for several decades.

The technological advances in flexible plastics over the 1960s and 70s soon saw disposable sanitary pads and tampons become more leakproof and user friendly as plastic backsheets and plastic applicators were introduced into their designs. As these products became more efficient in “hiding” menstrual blood and woman’s “shame”, their appeal and ubiquity increased.

Even before Covid-19 imposed urgency around this issue, emerging environmental consciousness of menstrual waste resulted in an increase in a range of reliable and sustainable sanitary products

Most of the initial market for disposables was limited to the west. But in the 1980s some of the larger companies, recognising the market’s vast potential, started selling disposables to women in developing countries. They received a considerable boost when in early to mid-2000s concerns around the menstrual health of girls and women in these countries saw a swift public policy push for the take up of sanitary pads. Public health initiatives across many of these countries began to distribute subsidised or free disposable pads. Pads were largely preferred over tampons because of the patriarchal taboos against vaginal insertion that prevail in many cultures.

As demand for disposable products has risen, so have the concerns over the sustainability of these products. With around 2 billion girls and women of menstruating age, the potential global menstrual waste burden can be significant indeed. The UK alone generates 200,000 tonnes of menstrual waste every year. Much of this waste ends up in landfills or in the oceans where the plastic and other non-compostable material in these products takes hundreds of years to decompose.

And that’s not to mention the supply chain issues that disposable products heighten.

Even before Covid-19 imposed urgency around this issue, emerging environmental consciousness of menstrual waste resulted in an increase in a range of reliable and sustainable sanitary products available to women. While small-scale innovations have existed for a while, these alternatives only took off in the early 2000s when big manufacturers such as GladRags and Mooncup entered the market. The two main sustainable product lines on offer are reusable cloth pads and the menstrual cup. The low lifecycle cost of these products also make them a much cheaper alternative to disposables. For example, menstrual cups are estimated to have less than 1.5 per cent of the environmental impact of disposables at 10 per cent of the cost.

Cloth pads mimic what women used historically and so are easy to adopt. Some have a foldable shape that does not resemble a pad when drying, like Lilypads. Some, like Safepad, have an antimicrobial top layer for improved hygiene. They typically last for 12 to 24 months. Most are biodegradable. Lifecycle costs are significantly lower than disposable pads and they are easier to manage when compared to traditional cloth, although hygienic use still requires commitment to washing and drying. Around 12 per cent of women in the UK are estimated to use reusable cloth pads. Ranges of “period pants” are also now on the market: underwear that absorbs menstrual blood and can then be washed normally and reused.

Menstrual cups, meanwhile, are flexible bell-shaped receptacles that collect blood (rather than absorb) and need insertion like tampons. In 2001, the most recognisable brand, Mooncup, started using medical grade silicone – a non-porous material resistant to bacteria – in its manufacturing. A single silicone cup can reportedly last for up to 10 years and are very popular among users. This clearly has huge implications for waste management. In 2018, the global menstrual cups market was estimated at $1.2bn and is expected to reach $1.89bn by 2026.

Although the markets for these products are growing, much of the focus of these companies has been on the west (echoing the initial phases for disposable pads). But clearly these products promise much for women in poorer regions of the world because they are a much cheaper and environmentally-friendly alternative to disposable pads.

I wanted to find out how much awareness there is of such products beyond the west, and how popular they would likely be if they were available. India is home to 20 per cent of the world’s menstruating girls and women and was a good place to look for answers. Despite the prevalent cultural norms that prevent women from openly talking about periods, around 300 women from 10 slum dwellings in the city of Hyderabad agreed to talk to my team and participate in our experiment.

Around 80 per cent of the women we talked to during our fieldwork used disposable pads, and none of them were aware of the more sustainable options.

This is unsurprising. Since 2011, the Indian government has campaigned for women to use them. This policy goal can be traced back to the NGO Plan India reported that just 12 per cent of Indian women could access sanitary pads. This raised concerns around the challenges women using traditional solutions could be facing in maintaining their menstrual hygiene and personal dignity. Traditional cloth is seen as unhygienic. While cloth is a hygienic menstrual solution, it requires adequate washing and drying, which is difficult to achieve in a country where taboos about menstrual blood are prevalent.

The general culture of silence around periods meant that women did not feel comfortable seeking information from better informed people

These concerns led the government of India to design national guidelines and strategies for the adoption of good hygiene. Above all, it favoured free or discounted distribution of disposable sanitary pads. This was seen as a tangible use of taxpayers’ money. It was also easy to piggyback on the marketing success of private companies that had already created public awareness and aspiration for pads.

Cheap commercial variants, government efforts and private philanthropy combined to cause a rapid surge in demand for sanitary pads. In less than five years, 2015-16’s National Family Health Survey reported pad users to have quintupled to 58 per cent, with rural users at 48 per cent and urban users at 78 per cent. Meanwhile, public menstrual health campaigns remain totally silent on other reusable options.

The other 20 per cent of the women we spoke to used traditional cloth, but the aspiration to switch to pad for the promised comfort and convenience was high. Affordability of pads was the main barrier to switching. We came across cases where women were prepared to give up essentials to be able to buy pads or bought pads for their daughters but not for themselves.

Many women, both cloth and pad users, consider cloth to be unhygienic. At the root of this belief are the myths and taboos that limit women’s ability to wash and dry cloth in a hygienic way. Many do not have access to private washing facilities and choose not to dry cloth under open sunlight for the humiliation of being seen by male members of the family and outsiders. Women tend to dry their menstrual cloth indoors, concealed in closets and hidden under mattresses. Such practices render the cloth unhygienic and contribute to the belief that cloth is inferior to pad. But we also found unhygienic practices among the pad users – it was common practice to use the same pad for the whole day or to use it on two consecutive days if the flow was light.

The general culture of silence around periods meant that women did not feel comfortable seeking information from better informed people (health workers, teachers) and ended up believing what they are told by women in the family and friends. Although it was common for women to have had some schooling and for younger girls to have studied in college with some attending university, we found that formal education made little difference to beliefs about menstrual products. A college student who participated in our study told us that “cloth was bad because my aunt’s friend became infertile because of it”.

What happens to the used pads?

The vast majority of the women in our study threw their pads out with routine waste. It is also common to see soiled pads floating in open streams and gutters next to dwellings. In focus group discussions, women told us about how they discarded soiled pads in the waterways close to their homes as it was the most convenient way of disposing it. Participants in their late 20s told us:

We have a huge river behind us, the pad will just flow away with it.

I wrap it [used pad] in a plastic bag, before throwing it in the river, how can I throw it just like that?

Much of the wet waste sifting in India is done by sanitation workers manually. We spoke to some sanitation workers involved in this work. One of them, speaking about his experience with sifting used sanitary pads from other waste, told us: “When I handle this mess, I feel my life is cursed.”

The plight of sanitation workers and the growing concerns around sanitary waste in cities has led the government to commission small-scale incinerators for schools, hospitals and government offices. These efforts are being scaled up despite high emissions associated with use of such incinerators.

While there is no concerted public effort towards informing women about sustainable alternatives, there are several small initiatives. Particularly noteworthy is the menstrual cup initiative by the government of Kerala. Launched in 2019, the Thinkal project distributed 5,000 menstrual cups free of charge to women from the municipality of Alappuzha. The idea emerged out of the devastation caused by floods in 2018, where women in the relief camps faced a massive problem with the disposal of their sanitary pads.

Other initiatives, mainly by small private enterprises, have come up with a variety of innovations like Uger’s and EcoFemme’s versions of reusable cloth pads, also teaching women how to make their own pads and Anandi’s compostable pad which needs deep burial and is hence better suited for rural areas. But without the backing of government policy and funding, these efforts remain small and sporadic and have little overall impact on knowledge and consumer behaviour.

The women who spoke to us during the fieldwork got their information on menstrual products from TV adverts and billboards. Other than traditional cloth and disposable pads, little was known about other menstrual products. None of the women had heard of commercially made reusable cloth pads or of menstrual cups.

This question is even more relevant now as Covid-19 exposes the vulnerabilities of global supply chains, with shortages in sanitary pad supplies emerging as a particular concern

We wanted to find out whether women’s choice of menstrual products would change if they knew more about other alternatives to hygienically manage their periods.

We decided to test this question with women from our study. We began by giving women complete and unbiased information on the entire range of menstrual alternatives, including compostable and traditional disposable pads, reusable cloth pads, tampons and menstrual cups. For each menstrual product they were informed of the pros and cons, including costs, hygienic use and implications for waste management. Then, some of the women were given a supply of disposable pads, others were given a supply of reusable cloth pads and the rest were given nothing.

We also wanted to test menstrual cups, but deep-seated patriarchal taboos against vaginal insertion meant that we could not secure approval from partner organisations in India who were worried about community acceptance. While we were disappointed at this, it also firmed up our resolve to understand the role of informed choice in women’s preferences for menstrual products.

We followed up with 277 women to find out about changes in their attitudes and preferences for menstrual products. Knowledge of menstrual materials and understanding of hygienic use was up significantly across all groups. Preference for sustainable menstrual materials also went up in all groups, with a 24 per cent increase overall. But the cloth and the information only groups saw a much greater increase (37 per cent) when compared to the group that received disposable pads (9 per cent).

This suggests that receiving disposable pads may have reinforced the original belief that “pad is best”, causing women in the pad group to ignore the information given about alternative menstrual materials. It is also possible that these women valued the convenience offered by disposables over other products.

Several women in the cloth and information groups expressed an interest in learning more about alternatives to pads, especially about menstrual cups, as little was known about these, and gave suggestions on how information could be shared:

Someone should tell us no? Such group discussions, teachers, government … they can put posters.

I feel I could use a menstrual cup.

These testimonials suggest that, despite the taboos associated with vaginal insertion in India, women are willing to experiment with such products. The results of Kerala’s cup trial will inform the future of this product in India and are worth watching out for.

What does this mean for the future of menstrual management in India and elsewhere? This question is even more relevant now as Covid-19 exposes the vulnerabilities of global supply chains, with shortages in sanitary pad supplies emerging as a particular concern.

The menstrual product landscape has evolved considerably in the last few years and new sustainable innovations continue to emerge. But if women have information about and access to just disposable sanitary pads, then the demand for this alone will continue to increase – but not necessarily in an informed or hygienic way. The silence around alternatives continues largely because of social taboos surrounding menstruation which makes discussing talking about it difficult for everyone involved.

The dominance of disposable pads, meanwhile, is driven by companies motivated by profits and this hegemony continues as policymakers, community stakeholders and women watch in silence, not knowing the real cost of pads or of the availability of alternatives. The only way to reverse women and public health initiatives choosing disposable pads is to provide complete and unbiased information on the full range of menstrual materials.

Despite the general caution attached to studies with small sample sizes, our results suggest that as a policy tool, informed choice has the potential to steer the menstrual product market in a sustainable direction. If given comprehensive information on all available menstrual products, women are likely to make a choice that considers not only costs to themselves and their health but also costs to the environment. Increase in demand for a range of products, including sustainable alternatives, is likely to incentivise the markets into improving availability and access to these.

Breaking the silence around menstruation is the key to a future where there is “period equity” – where every woman in every situation, pandemic or not, has the ability to hygienically and sustainably manage her periods.

Supriya Garikipati is an associate professor in development economics at the University of Liverpool. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments