A hundred years on from the 'cult of the clitoris' libel trial, let's remember that fake news is nothing new

Maud Allan created a scandal with her performances of Oscar Wilde's Salome, but it was bizarre accusations of her involvement in a pro-German, sexually perverted conspiracy that drew the interest of the press in 1918, reports Kevin Childs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s nothing new about fake news and the way the press uses it to manipulate opinion. A hundred years ago, as the Allies’ fortunes of war took a turn for the worse in the spring of 1918, a libel trial concerning an MP, a dancer, a semi-fictional princess and a dead playwright gripped the public imagination. With prime ministers and celebrities, sex and sapphic sorority in the mix, it would come to be the trial of the century.

Throw in homosexuality, foreigners and a supposed Black Book of potential fifth columnists in high places, and the real victims of the Western Front were consigned to the lists published on the back pages of The Times.

By the start of 1918, the First World War had seen millions of men punched, pounded and pulverised for three and a half years with little to show for it. Yet despite everything, for many at home, life and society went on.

In England, on 9 April, the famous Canadian dancer and actress, Maud Allan, played to a packed house of invited patrons in one of two performances of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, reprising the role of the Judaean princess who had danced her way to Fin-de-Siècle notoriety through poetry, images, music and, latterly, Allan’s own sensational performances in Europe and America as the ‘Salome Dancer’:

“Bare-limbed and scantily draped in filmy gauzes,” the critic of the New York Times had written, “diaphanous in texture and un-vivid in colour, she floats from one pose to the next, emphasising the plastic transitions with waving arms and raised legs and sundry poses of the head.

''Miss Allan ... is more beautiful in face and figure than some of them, and she has a grace, a picturesque personal quality, which is all her own.''

Thus, Allan shimmered across the London stage in a costume consisting of little more than beads, her free dance and shedding veils having already set the pulse of Margot Asquith, wife of the British prime minister, racing.

The king, prompted to inquire why she had never before performed in London was met with the bold answer: “Only, Sir, because I’ve never been asked.”

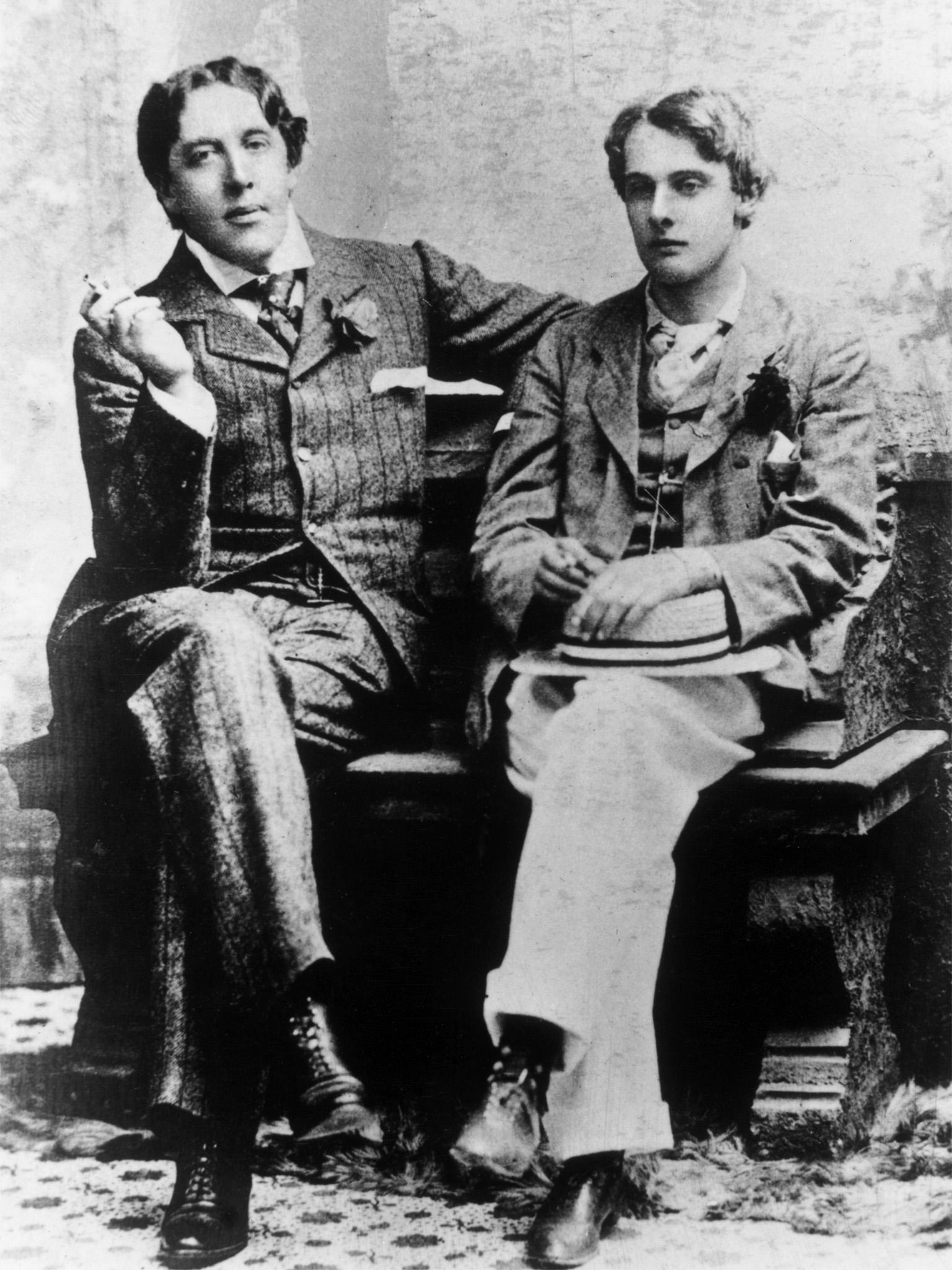

The truth is, it was Allan’s pluck and celebrity which had first suggested to the friends of Oscar Wilde, still a name barely whispered in England, a way of bringing him back into popular favour – of rehabilitating his art after 18 years of critical inhumation, during which his works had been stripped from bookshop shelves.

It seems now an odd time to choose to memorialise a writer who had died in Paris in poverty in 1900, despised by his compatriots. But as the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd and the attrition of Passchendaele ground on in late 1917, The Times theatre critic, Jack Grien approached Wilde’s literary executor, Robert Ross, with a proposal for a private production of Wilde’s still-banned play.

Coincidentally, Maud Allan was then kicking her heels in London looking for a vehicle that would steer her come-back.

Although the 44-year-old was known for her dancing not her acting, she had appeared in a couple of films, and it was, perhaps, ironic that she was to return to a tried and tested formula from her beads and gauzy heyday, though in a form that was all the more notorious for never having been publicly staged in Britain.

In this country, Salome was the stuff of rumour only. A heavily cut version of Richard Strauss’s opera, its libretto based on Wilde’s play, had been performed at Covent Garden in 1910 and never since. Allan, though, was the pin-up princess, posing for the symbolist painter Franz von Stuck as a wild Bacchic Salome in 1906, and swaying erotically across postcards and posters on both sides of the Atlantic for nearly 10 years.

She had been born Maud Durrant in Toronto in 1873, moving to the United States at the age of six. She was intensely musical, becoming a very fine pianist as a child. It was her mother’s plan that she raise the family’s fortunes as a professional on the international concert circuit, and so a young Maud was packed off to Berlin from San Francisco to that end.

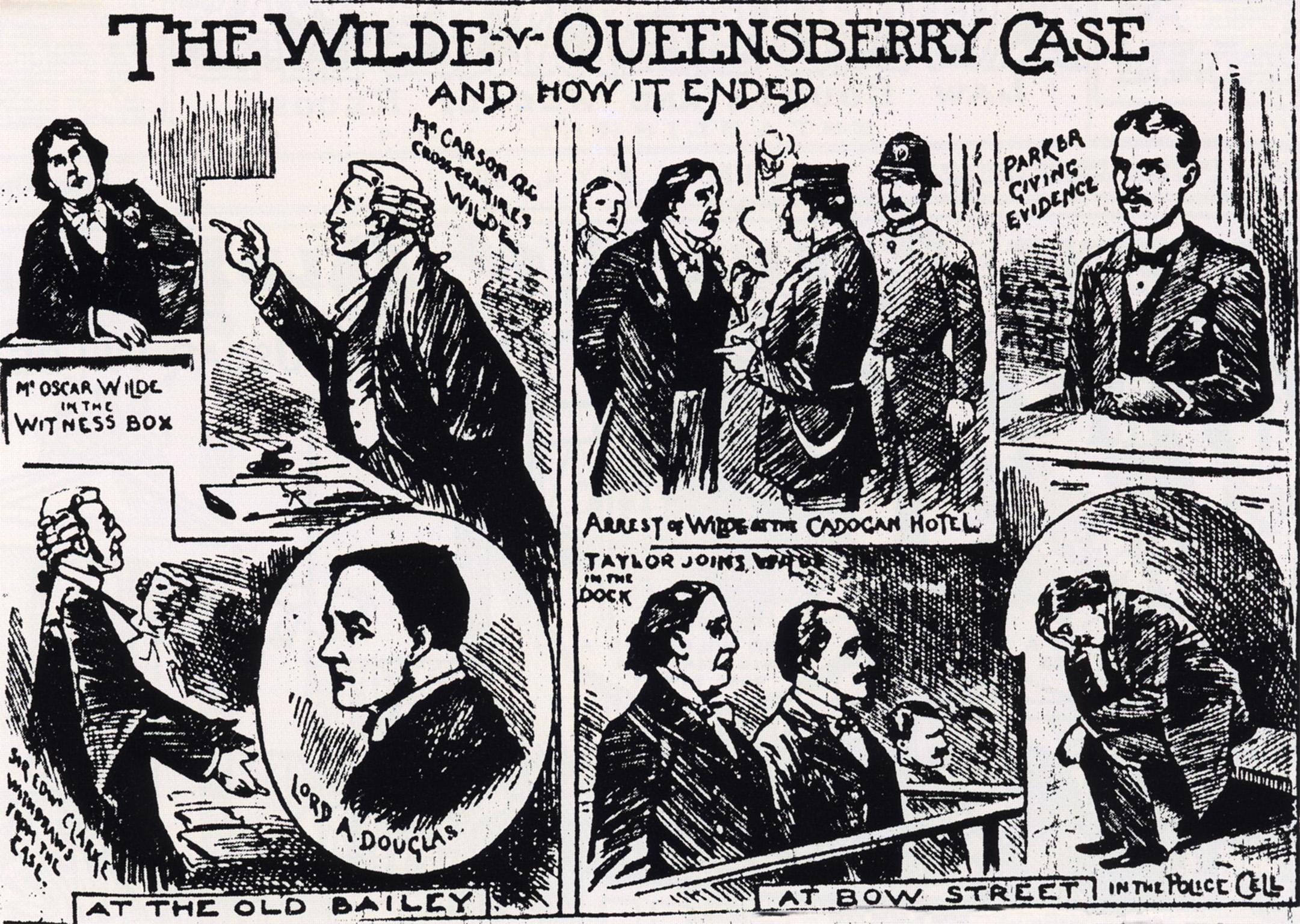

While Oscar Wilde embarked on the libel trial that would ruin him in 1895, Maud was setting sail for Europe. She didn’t then know that her beloved brother Theo was on trial too, for a bizarre and dreadful double murder of two young women. Convicted and hanged four years later, Maud would be haunted by Theo’s death, changing her own name to Allan and abandoning the concert hall for the dance studio.

She emerged from a period of introspection as part of a new movement in solo dance performance that challenged the restrictions of ballet and prefigured modern dance, and with the courage to take on a persona that sent shivers down many an Edwardian spine in Europe and America.

The Vision of Salome earned her the epithet of ‘'aesthetic dancer’'. If anyone could pull off the role written for Sarah Bernhardt, Maud Allan could.

But the public mood in Britain in 1918 was vastly different from the Belle Époque hedonism of 10 years earlier. The war was entering its fifth year with little sign of an end, victorious or negotiated. The public mood was a toxic mix of blatant jingoism and paranoia.

Only a few months before, another celebrated free dancer, Marta Hari, who had also dabbled with the Salome myth, had been shot by the French on trumped-up charges of spying for the Germans. The roar of German guns around Ypres could be heard in the Home Counties and civilians fretted about German gun boats in the Channel over their tea and cake.

When the play was advertised early in 1918, with Allan announced in the starring role, an article appeared in Vigilante, a right-wing, raging bull dog of a journal, under the heading “The Cult of the Clitoris”, suggesting that Allan was a lesbian and German sympathiser.

Her career, like many other artists and performers in 1918, had first taken off in Berlin and Munich – and that the whole business was part of a conspiracy to undermine the war effort through sexual perversion, blackmail and espionage.

Behind the libel was the independent MP Noel Pemberton Billing, a smooth, caddish man with an inglorious war record, who had been gunning for Allan for a couple of year

Behind Billing was a strange alliance of bitter literary failures, lunatics and proto-fascist opportunists, which included, some say, military top brass, press barons and Wilde’s original collaborator on the play, Lord Alfred Douglas, or Bosie as he’d always affectionately been known.

Allan, with Grien alongside, sued for libel but rather than forcing a climbdown, what ensued was a media witch hunt orchestrated by Billing and his backers including the newspaper titans Lord Northcliffe and Lord Beaverbrook, who hounded them and anyone vaguely connected with the Salome project.

Billing and his associates continued to focus on what they called the Berlin Black Book, a supposed catalogue of 47,000 names, German agents and fifth columnists, homosexuals, lesbians, literary figures, artists, politicians, lawyers, even soldiers, whose activities apparently allowed the Germans to “propagate evils which all decent men thought had perished in Sodom and Lesbia”.

While some claimed to have seen the book, it was always just out of reach, behind the German lines, phantom-like, though all the more real for being so, emerging in Bavaria or Vienna or anywhere British intelligence services or the British press, which lapped up Billing’s vomit, couldn’t get hold of it.

The Vigilante article had claimed that to attend Allan’s private performances of Salome, “one has to apply to a Miss Valetta, of 9 Duke Street, Adelphi, WC. If Scotland Yard was to seize the list of those members I have no doubt they would secure the names of several of the first 47,000.”

Herbert and Margot Asquith were implicated, as was Robert Ross, who only wanted to see the reputation of his old friend and lover restored, “while diplomats, poets, bankers, editors, newspaper proprietors, members of His Majesty’s household follow each other with no order of precedence”.

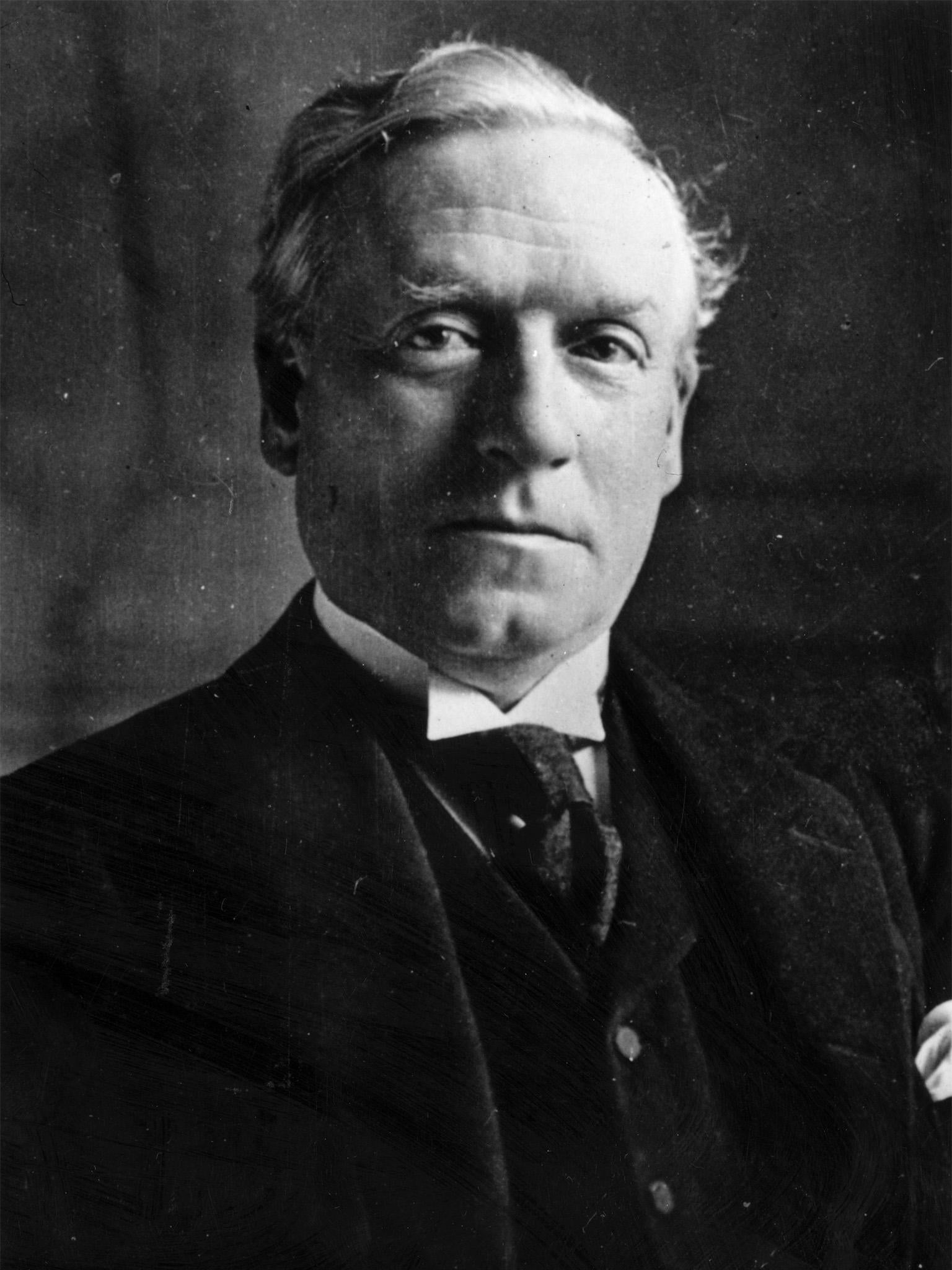

Billing and his conspiracy theories didn’t just concern Allan, however, but also represented a liability as far as the government was concerned. A counter-plot was said to have been hatched, with the connivance of then prime minister David Lloyd George, widely believed now to favour a peace deal with Germany.

At its heart was a young woman called Eileen Villiers-Stuart, who was to seduce Billing into some compromising position whereby he might be blackmailed with salacious photographs.

If true, the bizarre scenario backfired: Villiers-Stuart fell for Billing over dinner at the Savoy and disclosed the government’s plans for him.

She was now on his team and a star witness for the defence as she was prepared to claim that, through her connections in high places, all of whom had conveniently been killed in the war, she had actually seen and read parts of the infamous Black Book.

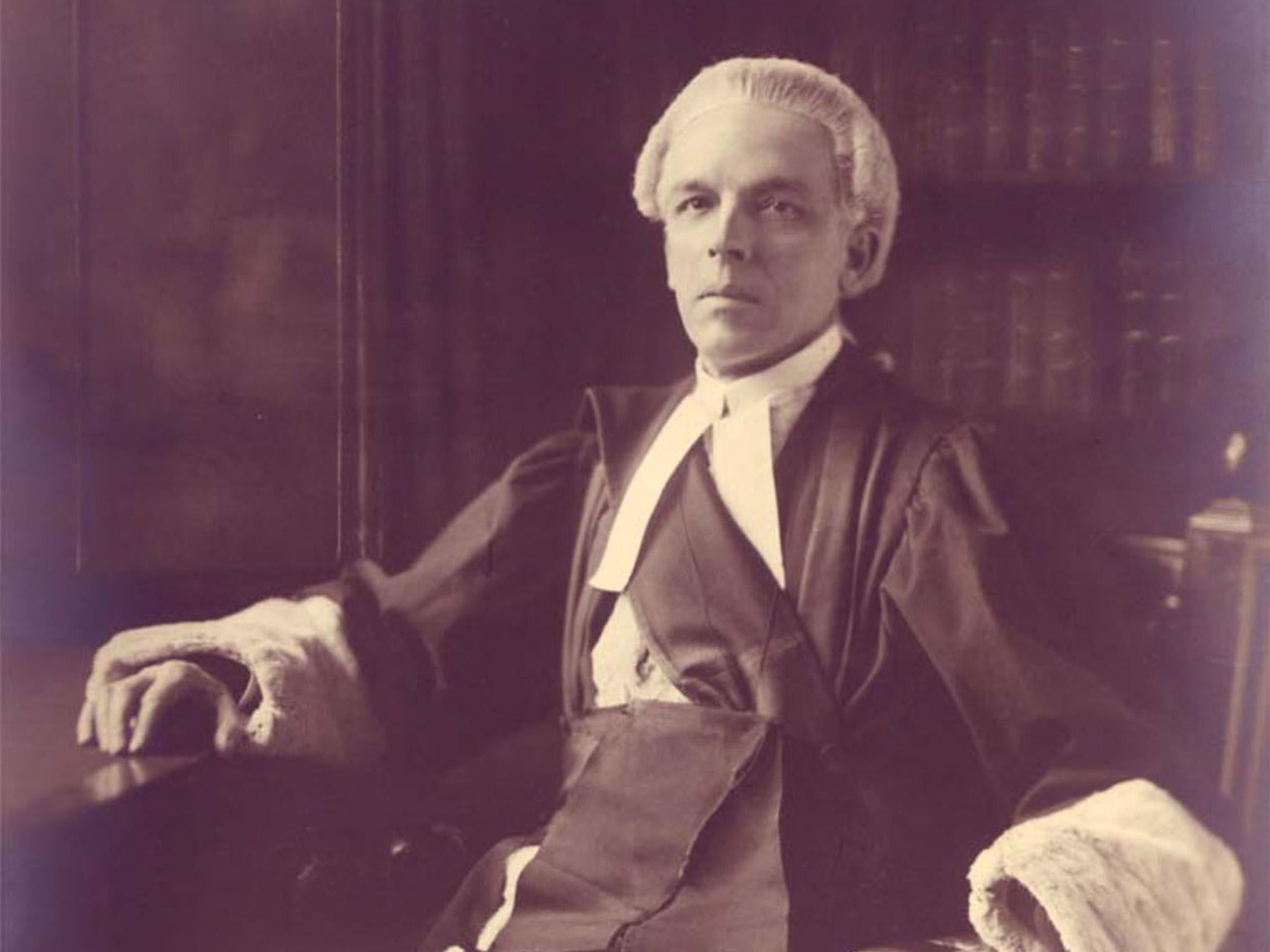

The hearing began on 29 May at the Old Bailey, the very court that had seen the conviction of Oscar Wilde himself – a fact the presiding judge, Charles Darling, seemed to find tremendously gratifying. Billing, representing himself, went on the attack, dredging up the sorry fate of Allan’s brother as ‘'evidence'’ of her own innate viciousness.

Did she, he demanded, know what the clitoris was? Yes, she replied. Was she a medical practitioner, surely the only person who ought to know?

No. It wasn’t something nice ladies knew about, of course, but she had once collaborated on illustrations for a sex manual for women in Germany – hardly something she could confess to under the circumstances. Knowing what it was offered proof, through a twisted sort of logic, that she was one of those perverted devotees of the “cult of the clitoris”.

Next came Villiers-Stuart. When Darling tried to silence her over allegations about the Asquiths, Lord Haldane and numerous others, she shouted: “You daren’t hear me!” Pointing at the judge, Billing, who had been questioning his witness, then demanded, “Is Mr Justice Darling’s name in that book?”

“It is,” she loudly replied, at which point Mr Justice Darling banged his gavel and lost control of his court.

There was no Black Book, of course, there was no pro-German conspiracy, and if Allan did indeed have passionate relationships with other women, it had no bearing on the safety of the realm.

It was all, in the truest sense, fake news, but the public became bloated on breathless, lurid and, for the most part, fanciful press accounts, especially in Lord Northcliffe’s Times, Daily Mail and London Evening News. A sort of madness descended. Even officers in the trenches, who ought to have had more important things to discuss, chewed over the riper gossipy aspects of the case with relish.

Alfred Douglas, who had also been called to give evidence for the defence, took the opportunity to turn the trial into an all-out attack on Oscar Wilde and Robert Ross.

Douglas had rarely found his moral compass. His devotion to Wilde had turned to loathing of his past associations and his recent adoption of Catholicism added a convert’s zeal to his already volatile character.

Fury had soured his good looks and turned him into a sort of caricature of his father, the mad pugilist Marquis of Queensberry, as he angrily pursued the memory of the man who, in the end, had made him famous, popping up in one trial after another whenever the opportunity to persecute Wilde’s friends, and Robert Ross in particular, permitted.

Never mind Billing’s insane conspiracy theories, it was Wilde who was the real target of Douglas’s venom, which had been brewing for years, stoked by re-readings of Wilde’s brilliant palinode, De Profundis, which the saddened and chastened playwright had composed in prison as a sort of apologia aimed at exposing Douglas’ monumental selfishness.

Besides all this, Douglas and Allan had their own history: 10 years earlier he’d published a damning notice of her Salome dance and she’d struck him across the face at a garden party in retaliation.

Inevitably then, Wilde took centre stage as the erstwhile lover sought both to obliterate his past and retain the limelight that he had gained by Wilde’s association, surely two entirely incompatible ambitions.

“I think [Wilde] had a diabolical influence on everyone he met,” Douglas told the court. “I think he is the greatest force of evil that has appeared in Europe in the last 350 years.”

Referring to the “cult” of Oscar Wilde – an echo, surely, of the original Vigilante article – Douglas named Ross and his associates as its members.

“I’m very worried about dear Robbie”, wrote the poet Siegfried Sassoon to a mutual friend, and Ross tried hard to keep a low profile, wishing he’d never agreed to the performances and remembering Wilde’s own disastrous decision to sue 20 years or so previously.

The odd and improbable alliance between a dead playwright and a bizarre war-time conspiracy doesn’t seem to have troubled anyone on the defence team or among the public in the gallery, who were wholly enthralled by Billing’s performance and the reporting of it in the press.

Neither did the fact that the translation of Salome used by Allan and Grien had been in large part Douglas’s own. In fact, when Justice Darling referred to him as co-author of Salome, Douglas flew into a rage and had to be evicted from the court room, returning a few minutes later to ask if he might have his hat which he’d left on one of the spectators’ benches.

Even special branch assistant commissioner Basil Thompson, who was not above shuttling his own conspiracy theories in the service of the state, wrote: ”Everyone concerned appeared to have been either insane or to have behaved as if he were.”

Billing played on fears of invasion, knowing that the general detestation of homosexuality and the British appetite for gay scandals would work in his favour. He had even packed the gallery with wounded soldiers from the front to remind his audience of the sacrifices made by the flower of British youth for these disreputable degenerates and traitors.

Not for the first time, and certainly not for the last, a nasty concoction of treachery and homosexuality, with a dash of decadence and xenophobia thrown in won the day.

After all, wasn’t homosexuality a foreign vice – in this case specifically a German vice? Billing could point to the notorious Eulengberg Affair before the War and the contemporary writings of German sexologist Richard von Kraft Ebing.

And weren’t Allan, Grien, Ross and a whole host of others, foreigners? Even Douglas could play the righteous man chastened by youthful indiscretion at the hands of a foreigner – Wilde was Irish for these purposes.

On the last day Billing spoke of the ”mysterious influence which seems to prevent a Britisher getting a square deal” (what he had previously dubbed ‘The Unseen Hand’). While Darling attempted in his summing up to throw the whole question of the Black Book out, it was too late. After an hour and a half of deliberations, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty and the court erupted into wild cheers.

Just as Billing, flanked by wife and mistress, enjoyed the approbation of the crowd outside the Old Bailey, and Maud Allan wept quietly within, Allied forces were finally putting an end to the German offensive against Paris. The war had turned.

Grien resigned from The Times. Robbie Ross was visited by the police and questioned about his friends and associates. A few months later he died of a massive heart attack in the drawing room of his flat on Half Moon Street that he’d recently decorated with expensive dark gold wallpaper as a cock-a-snook gesture at government demands for war-time austerity.

Allan’s career skidded into the doldrums for good, and the brief revival of Wilde’s name and genius was buried once more in infamy.

“You don't read The Daily Mail, I suppose,” wrote the poet Charles Hamilton Sorely to his father in the early years of the war, “but reading it out here opens one's eyes to the dangerous influence the press is beginning to arrogate and may ultimately attain.

That paper makes one sick, not because what it says is untrue (for the most part) or unsound or insincere: but because of its colossal egoism … and its power of anticipating public opinion by 24 hours and giving it just the turn in the direction The Daily Mail wishes.”

By 1918, the paper’s owner Northcliffe, a sponsor of Billing’s campaign, was able to prep and prod the reading public into which ever direction he and his editors deemed appropriate.

Truth was a victim, but in a sense that didn’t matter: propaganda and circulation were supreme. Even ‘respectable’ papers – The Times was also Northcliffe’s – were instruments of the Black Book agenda.

“One can't imagine a more undignified paragraph in English history,” wrote the Asquith’s daughter Cynthia, “…that three-quarters of The Times should be taken up with such a farrago of nonsense!”

Of course, Allan and Grien, Ross and poor dead Oscar were victims of Billing’s political ambitions – he cared little for the veracity of his case, it was just a means of plugging the idea of the Black Book. But that idea wouldn’t have caught on were it not for the reporting in the press: the blind leading the blind.

Time would unravel it, of course. A few months later, in September 1918, Eileen Villiers-Stuart was convicted of bigamy and confessed that her evidence in the Allan case had been entirely fabricated and rehearsed with Billing beforehand.

In 1921 Billing resigned his parliamentary seat, rather than risk losing it, and Douglas finally found himself behind bars after libelling Winston Churchill, of all people.

There’s a photograph, published in one of the newspapers during the trial, which shows Billing arriving at the Old Bailey in an open car seated between his wife and Eileen Villiers-Stuart. He looks straight ahead, Mrs Billing turns away, but Eileen looks directly at the camera.

Her eyes are shaded, her mouth a slick of deep red lipstick and she holds an ostentatious fur stole around her shoulders, despite the early summer warmth.

Did she wonder whether the camera ever lies? Whatever the caption or the tenor of the article that accompanied the photograph, she would forever be the Black Book mistress, who perjured herself for a worthless sociopath and ruined the lives and reputations of too many men and women.

No doubt she thought herself heroic then, but it’s Maud Allan, the pioneer of queer art, who seems the hero a hundred years on, braving the dubious moral probity of the British press to bring back to life that other great, queer artist, Oscar Wilde.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments