Opioid addiction knows no colour, but its treatment does

Opioid addiction treatment is sharply segregated by income in New York, where there is a clear two-tier system. Jose A Del Real meets the poorer people relying on the highly regulated clinics they must visit daily to receive their plastic cup of methadone

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a street lined with rubbish trucks, in an industrial edge of Brooklyn, dozens of people start filing into an unmarked building before the winter sun rises. Patients gather here every day to visit the Vincent Dole Clinic, where they are promised relief from their cravings and from the constant search for heroin on the streets.

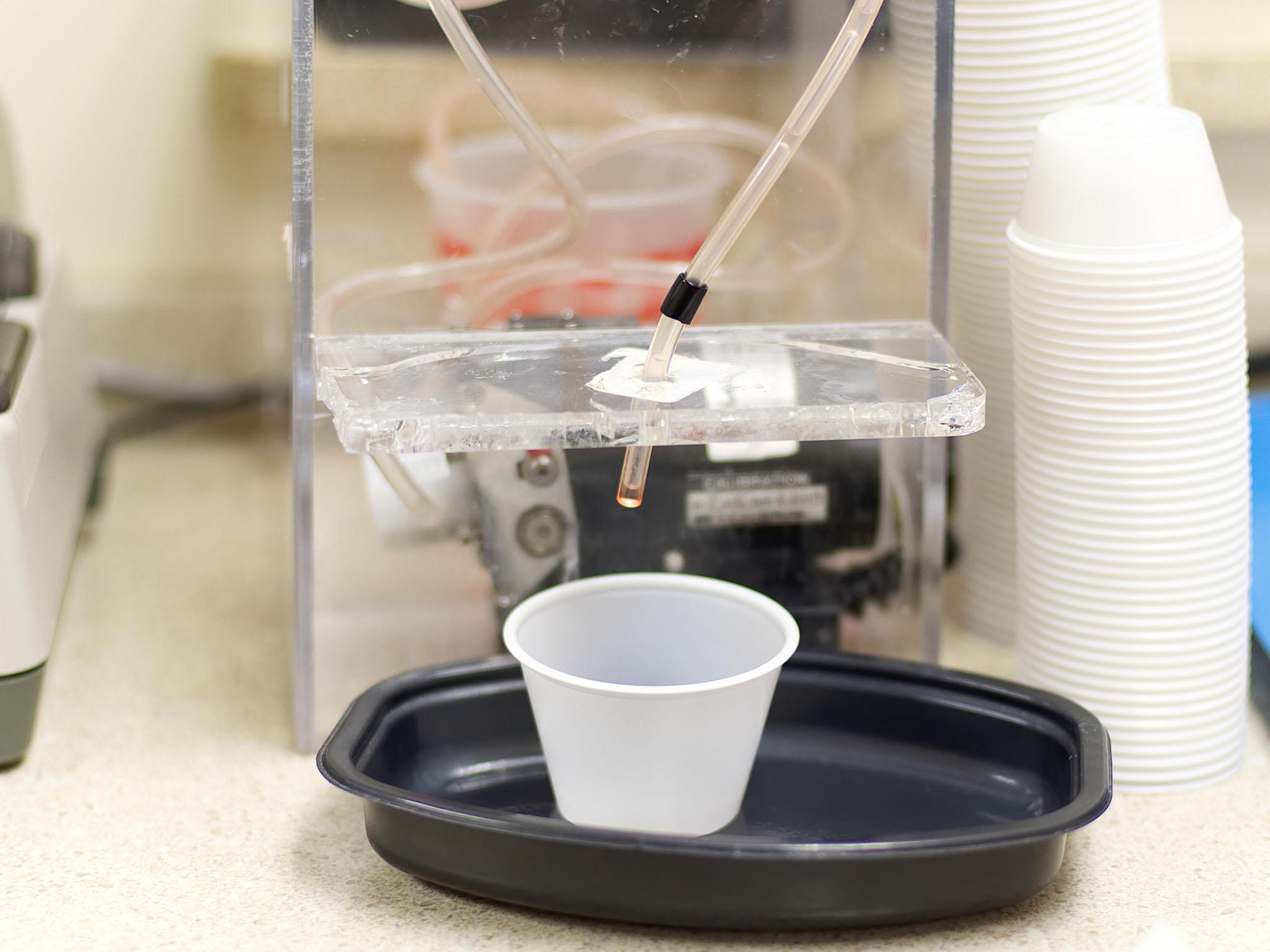

Robert Perez exited the clinic on a recent Wednesday and walked towards the subway, along the Gowanus Canal. Within the clinic’s antiseptic blue walls, he had just swallowed a red liquid from a small plastic cup. The daily dose of methadone helps Perez, 47, manage withdrawal symptoms as he tries to put decades of drug abuse behind him.

“I wish I didn’t have to come here every day, but I have to,” Perez says outside the clinic. “If you don’t do it, you’re sick. You wake up sick.”

Perez is not alone. For recovering users without money or private health insurance, these clinics are often the only option to get their lives on track, even as less cumbersome alternatives have become available for those who can pay for it.

In New York City, opioid addiction treatment is sharply segregated by income, according to addiction experts and an analysis of demographic data provided by the city health department. More affluent patients can avoid the methadone clinic entirely, receiving a new treatment directly from a doctor’s office. Many poorer Hispanic and black individuals struggling with drug addiction must rely on these highly regulated clinics, which they must visit daily to receive their plastic cup of methadone.

Perez expresses gratitude at the chance to treat his addiction, but laments that his days are now oriented around the clinic. He had commuted 45 minutes from Bushwick to receive his methadone, a highly regulated opioid used to treat heroin and painkiller dependence, as he does every day of the week. Sometimes he waits in line at the clinic for an hour for his turn. “You have to come every day. I hate it, I hate it, but you have to do it.”

This is what opioid addiction recovery is like for more than 30,000 patients enrolled in New York City’s approximately 70 methadone-based treatment programmes, which provide medication-assisted treatment, counselling and other social services. Hundreds of thousands of patients across the country are enrolled in similar programmes, which often receive government funding and are covered by Medicaid in New York.

For more than 40 years, methadone was the most effective method for people addicted to heroin to keep their cravings in check. But in 2002, the Food and Drug Administration approved another medication to treat opioid addiction: buprenorphine, sold most widely in a compound called Suboxone. Both methadone and buprenorphine are extremely effective in keeping recovering users from relapsing, according to medical research, but Suboxone is engineered to reduce the possibility of abuse and overdose. Crucially, the medication can be prescribed in doctors’ offices and then taken at home.

Many hoped that buprenorphine could mean an end to the daily hurdles to receiving treatment for tens of thousands of patients: no additional commute, no security check, no waiting, no line for the plastic cup.

But today in the city, that is primarily true only for middle-class or upper-middle-class patients seeking help with their addiction.

More patients arrived at the clinic as Perez spoke. They were nearly all Hispanic or black. Those who are white, like Melissa Neilson, are often unemployed or have few resources to dedicate to recovery. She and her partner, JC Marin, visit the clinic from Copiague, Long Island, in a taxi paid for by Medicaid. More than two hours each way, six days a week, for their daily dose.

Methadone treatment was pioneered in New York, a city with a deep history of opioid addiction, and access to the treatment is easier here than anywhere else in the United States. But because methadone is highly regulated – owing to fears that it could be sold in illegal markets – physicians can provide methadone for addiction treatment only in specialised clinics like Vincent Dole. Employment, child care, unexpected emergencies and other life events have to be oriented around the clinic. On the street, methadone is sometimes referred to as “liquid handcuffs”.

The limited data recently made available by the New York City health department hints at structural discrepancies in access to treatment that become obvious during visits to these clinics. In New York City, 53 per cent of participants in methadone programmes are Latino, 23 per cent are black, and 21 per cent are white, according to 2016 health department data.

The city said it does not keep track of the income or race of buprenorphine patients, and data on buprenorphine treatment demographics is sparse at the national level as well. A study published in 2016 in Drug and Alcohol Dependence, a scientific journal, found that buprenorphine and methadone access were correlated with income and ethnicity in New York City. Without broad government surveys, precision is difficult; the report lamented that no nationally representative data on ethnicity or income has been published since 2006, when a survey by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration showed that 92 per cent of buprenorphine patients were white.

In 2016, according to data provided by the city, more than 13,600 New Yorkers filled prescriptions for Suboxone at least once – and nearly 80 per cent paid for the medication with private insurance. No reliable payment data is available for methadone in New York City, but a representative for the Dole clinic said virtually all its patients receive Medicaid.

City Hall has sought to increase the number of physicians certified to prescribe buprenorphine. Mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife, Chirlane McCray, have spoken about the urgent need to expand treatment options. But despite their efforts, the growth of buprenorphine prescribers has been slower than many experts would like.

“What this crisis is again calling attention to is the need for more health professionals to step in,” says Dr Hillary Kunins, an assistant commissioner at the city heath department. “I think because of stigma and because of inadequate education in health professional settings, physicians were not taught to think about addiction in their specialities.”

Dr Andrew Kolodny, an opioid addiction expert affiliated with Brandeis University, says regulatory burdens on buprenorphine by the government – like the eight-hour certification requirement – has likely discouraged physicians from offering it in their practices.

He adds that many doctors who are certified to prescribe buprenorphine choose not to after realising the complicated task of treating patients with substance abuse problems. Those who do work with the patients often do not accept insurance, he said, in some cases because demand is high and they can make more money charging directly. That means the patients must have enough money to pay out of pocket for the visit.

“Your insurance will pay for the prescription, but you have to pay for the doctor,” he says.

What has emerged is a private and expensive market for buprenorphine treatment.

The fight for equity in treatment for opioid addiction can feel like a multifront battle; in some cases, experts struggle just to convince policymakers and nonspecialists that prescribing an opioid to a drug addict is a reasonable course of action. Numerous studies confirm that methadone and buprenorphine are both highly effective for treating opioid addiction. (The effectiveness of detoxification – total abstinence from opioids – for long-term addiction management, which is strongly emphasised in popular treatment narratives, has been called into question by experts and by medical research. It can also leave those who relapse at higher risk for overdose.)

The clinics themselves are often vulnerable because they work with such a highly stigmatised population, especially in rapidly gentrifying areas. Perez was enrolled in the Cumberland Clinic on Flatbush Avenue, near the Barclays Center, before it closed late last year. Mount Sinai Beth Israel, which ran the clinic and also runs the Dole facility, had its lease for the clinic terminated when a private owner sold it to a development company. A high-rise development is going up in its place.

Dr Helena Hansen, a research psychiatrist and cultural anthropologist, says racially charged stereotypes historically associated with opioid and heroin addiction have led to persistent stigma around methadone. Methadone, she says, carries criminal connotations that can be traced back to the war on drugs rhetoric that escalated in the 1960s.

Methadone clinics, Hansen says, can often look and function like probation offices. “And they’re organised as such,” she explains. “People line up, they have to have their urine checked, you have to come every day.”

Noa Barreto, 43, started using heroin about four years ago after “a tragic loss” in his life. He was dealing drugs at the time and, he says, he “started getting high on my own supply”. Two years ago, after battling with addiction, he decided to enrol in methadone treatment. Barreto says after he overcame the initial shock of entering treatment, he was able to reorient his day around the methadone doses.

“It’s like a job, you know?” he says. “Once you get on it, and you become accustomed to it, it becomes easy. You get up in the morning and it becomes a routine.”

This month, Barreto says, he had to turn down a job offer because it would interfere with his ability to get to the methadone clinic. Some patients who have made progress with their addiction are trusted with limited “take home” bottles, but the process can take months or years. And with good reason. When abused, methadone carries an extremely high potential for overdose. (Barreto qualifies for take-home bottles on the weekends; he visits the clinic five times a week.)

Rick Harwood, deputy director at the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors, says the demographics of methadone clinics could be partly explained by patients who are middle class or white being less likely to see methadone as a treatment option.

“Ask people, middle class or otherwise, would they go to an opioid treatment programme, a methadone clinic?” Harwood says. “Not too many of them probably would. A lot of times they’re inconvenient to where they live, or are in depressed neighbourhoods, places people might consider unsafe.”

Harwood says low-income patients could conceivably access buprenorphine treatment at methadone clinics, if they are interested. But methadone clinics are often overwhelmed with methadone logistics and the social service programmes they are required to provide; buprenorphine consultations are an additional service. That can produce an information gap in addition to a financial one. Kolodny also says that, realistically, buprenorphine treatment cuts against the business interests of for-profit methadone clinics, which are becoming more common nationally.

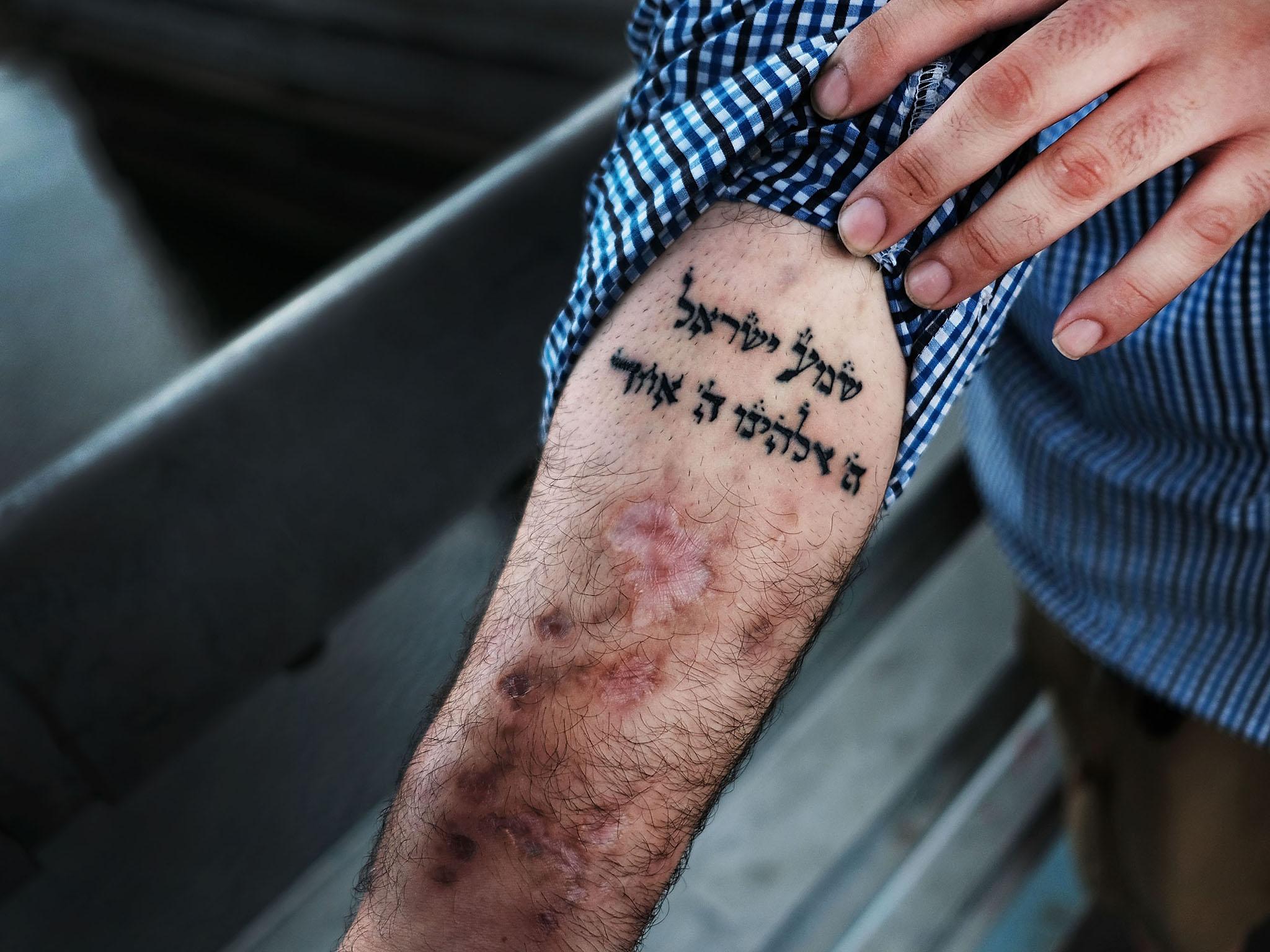

Perez could be served well by the flexibility that Suboxone would give him as he manages employment as a tattoo artist. He says he would like to consider transitioning to buprenorphine treatment, but does not know where he can get it or how he might pay for it.

Meanwhile, some long-term users, including Neilson, say methadone has a more satisfying effect than buprenorphine.

“I tried to go back on Suboxone,” she says. “I didn’t feel sick, but I still wanted to get high. I had no energy, not even to get up and take a shower, let alone leave the house or stand up.” She adds that she’s afraid to transition away from methadone. “The sickness is not something I can describe to anybody. This is a better way to do it. Methadone. I’m never getting off.”

Dr Chinazo Cunningham, a Bronx-based addiction medicine expert who has worked with vulnerable populations for decades, says she “just knew” a two-tier system would emerge, excluding many patients. But she stresses that methadone programmes do important work for patients with complicated needs. Beyond drug treatment itself, the clinics provide a critical reprieve for patients without support networks.

“The people whose lives are a little bit more chaotic could benefit from methadone, or people who have poly-substance use, alcohol or cocaine, or others,” says Cunningham, who is affiliated with Montefiore Medical Center, in the Bronx. “Primary-care settings have limited resources and maybe can’t take on someone who is more complicated.”

Such was the case with Jonathan Roman, 33. He is homeless and sleeps in his van. He arrived at the Vincent Dole clinic about eight months ago without insurance, looking for help with his addiction; the team at the clinic helped him enrol in Medicaid. They are also helping him find housing, he says, while speaking glowingly about his counsellor at the clinic.

At one point, Roman estimates that he was using $300 (£215) of heroin a day, which he paid for by “stealing and doing side jobs”. People took advantage of his addiction, he says, giving him work in construction and as an electrician but then paying him less than they should because they knew he was desperate. His dealer used to pick him up on payday, at 4:30 am, and drive him to the nearest ATM.

Roman says that for him and countless other patients, the concentrated resources available at the clinic provide a life-support system. He qualifies for take-home bottles of methadone, but he has refused them; the discipline of coming to the clinic each day helps him, he says.

“You can be on the good path, but if something happens in your life, and you think you’re not worth anything, or that life is not worth living, you do stupid things,” he says. “Now I think about all the things that I do and I laugh sometimes. I was this close to losing my life.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments