‘The human impact is clear’: Ocean heat continues to rise

The planet’s air temperature has been rising for decades but it wobbles up and down, write Chris Mooney and Brady Dennis. The ocean doesn’t do the same dance, it changes more slowly – and more deeply

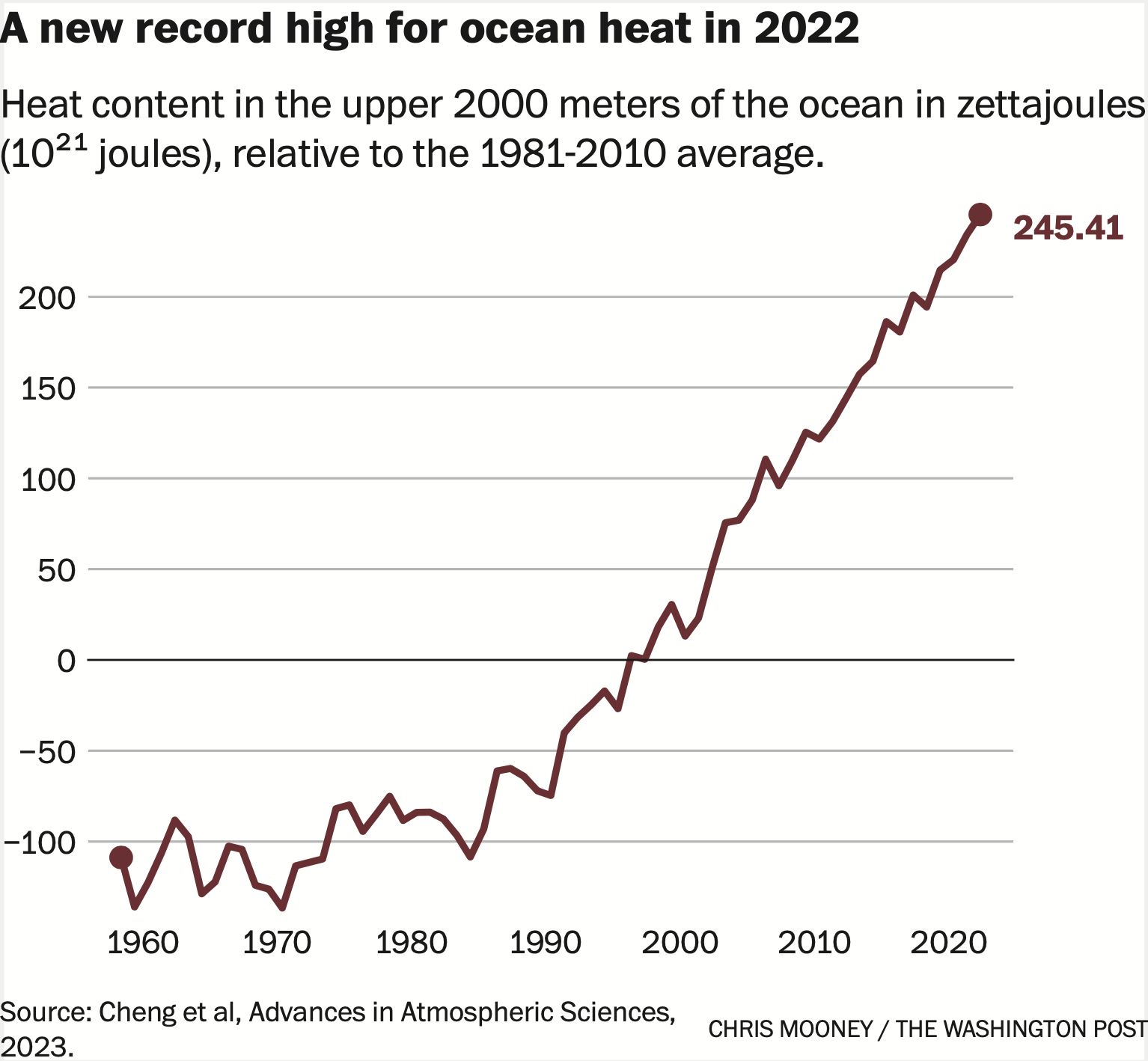

The amount of excess heat buried in the planet’s oceans, a strong marker of the climate emergency, reached a record high in 2022, reflecting more stored heat energy than in any year since reliable measurements were available in the late 1950s, a group of scientists reported last Wednesday.

That eclipses the ocean heat record set in 2021 – which eclipsed the record set in 2020, which eclipsed the one set in 2019. And it helps to explain a seemingly ever-escalating pattern of extreme weather events of late, many of which are drawing extra fuel from the energy they pull from the oceans.

“If we keep breaking records, it’s kind of like a broken record,” says John Abraham, a climate researcher at the University of St Thomas in Minnesota and one of the authors of the new research published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

The planet’s air temperature has been rising for decades, but it wobbles up and down and does not set records every single year. Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service recently ranked 2022 as the fifth-hottest year on record for the atmosphere, with other expert rankings soon to follow.

The ocean doesn’t do the same dance. It changes more slowly – and more deeply. As climate change takes hold, natural ocean variations in temperature matter less and less, Abraham says, leading to a string of consecutive records in recent years, with 2018 being the last year that was not a record.

More than 90 per cent of the excess warming that results from the planetary energy imbalance, in which more solar heating enters the Earth’s system than escapes again to space, winds up in the ocean, the researchers say. Scientists began their record of ocean heat in 1958 because it is when measurements became dense enough, and accurate enough, to give a full global picture of the temperature trends down to considerable depths.

“Oceans contain an enormous amount of water, and compared to other substances, it takes a lot of heat to change the temperature of water,” Linda Rasmussen, a retired researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who was not involved in the work, says in an email. “The fact that we’re seeing such clear increases in ocean heat content, extending over decades now, shows that there is a significant change under way.”

The new research suggests that the rise in heat contained within the upper roughly 1.25 miles of ocean water – an increase driven by a massive amount of absorbed energy measured in units known as zettajoules – represents the true pulse of climate change.

The amount of added heat in 2022 is around a hundred times larger than the total world electricity generation in 2021, the researchers said in a news release.

The study was led by Lijing Cheng of the Chinese Academy of Sciences with numerous collaborators at institutions in China, Italy, New Zealand and the United States. It is based on two separate ocean heat data sets, one from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and one from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Both find 2022 to be the hottest year on record for the oceans, followed by 2021, 2020, 2019 and 2017.

A multitude of consequences flow from the fast warming of the oceans. Some are analogous to what is happening in the atmosphere. For instance, with the average temperature of the entire ocean warmer, it increases the odds of extremes in the form of ocean heat waves in certain regions. Just like in the case of atmospheric heat waves over land, these can be very dangerous for living organisms.

“Some of the most productive and biodiverse marine ecosystems, like coral reefs and kelp forests, are very sensitive to temperature. We’re witnessing a real-life experiment to find out how resilient they are, how capable of adapting or migrating,” Rasmussen says.

Other consequences of ocean warming are quite different from what happens in the atmosphere.

Warm ocean water expands, raising sea levels around the globe. At the same time, this expanding surface warm water is lighter and more buoyant than colder deeper water – which means that, in the words of scientists, the ocean becomes more stratified. Warm and cold layers mix less, which in turn traps heat at the surface – speeding the planet’s warming – while depriving the deeper ocean of oxygen and nutrients that cannot mix downward.

The ocean also loses oxygen because warmer water cannot hold as much of it, potentially leading to low oxygen zones that are a threat to marine life. The ocean also grows saltier in many regions, as the evaporation of warmer water leaves behind more salt – but in other regions, it actually grows fresher as rainfall increases. The study calls it a “salty gets saltier, fresh gets fresher pattern,” as evaporation wins out in some regions and rainfall in others.

Still, that’s just the beginning of the implications.

Kevin Trenberth, a co-author of the study and a scholar at the National Centre for Atmospheric Research, says the warming happening in the ocean can have direct consequences for events unfolding on land. For instance, he says, warmer water at the top levels of the ocean can help fuel more intense storms and the torrential rainfall that accompanies them.

“Those upper sea surface temperatures have really serious consequences for any storm that comes along,” he says, adding, “I think we are seeing some of the repercussions of that in the storms that are hitting California ... The heavy rainfalls are a direct consequence of this upper ocean heat content anomaly.”

In part, that is because more heat amounts to more moisture in the air, which can supercharge any storms that materialise. For every degree Fahrenheit that the air temperature increases, the atmosphere can hold about 4 per cent more water.

“The simplest way to think of this is, let’s assume the weather system and everything is going as it used to, but now we have a warmer ocean,” he says. “The atmosphere can hold more moisture. The warmer the atmosphere gets, the more moisture it can hold.”

The new research suggests that ocean warming, while strong and steady overall, does vary markedly around the globe. This is amplifying coastal sea level rise and may also be implicated in a strong warming trend affecting the coastal northeastern United States on land. “The Atlantic has been warming in spectacular fashion as a whole,” Trenberth says.

Wednesday’s study is the latest in a growing body of evidence that details the steady, relentless warming of the oceans. A study published in October in Nature Reviews found that the upper reaches of the oceans have been heating up around the planet since at least the 1950s, with the starkest changes observed in the Atlantic and Southern oceans.

The authors wrote that data shows the heating has both accelerated over time and increasingly has reached deeper and deeper depths. That warming – which the scientists said probably is irreversible through to 2100 – is poised to continue and create new hot spots around the globe, especially if humans don’t make significant and rapid cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

In its most recent assessment, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) wrote that it is “virtually certain” that the upper levels of the oceans have warmed over the past half-century and “extremely likely that human influence is the main driver.” Humans-caused emissions “are the main driver of current global acidification of the surface open ocean,” the panel wrote.

The greenhouse gas emissions that humans have produced since 1750 “have committed the global ocean to future warming,” the IPCC authors found. Over the remainder of the 21st century, the group said, ocean warming probably will be several times what it has been over the past five decades.

Trenberth reiterated that not all ocean warming happens equally. Storms can move heat from water to the atmosphere, currents redistribute heat around the globe, and just as worrisome hot spots emerge, so do cool spots, such as a notorious ocean region south of Greenland that has actually shown a decrease in temperature over time.

Despite the variability, there is no doubt that oceans on the whole are growing warmer over time – or what is driving that change.

“The human impact is clear when you look at the global picture,” Trenberth says. “The global ocean heat content is going up steadily.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments