‘Soldiers came to kill me: I’d be shot in the head and dumped in a shallow grave with my dead companions’

At the height of the war in 1969, 12,000 people a day starved to death in Biafra. More than 50 years later and the violent persecution of the Biafran people by the Nigerian state continues unabated. Nnamdi Kanu on the battle for self-determination

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was 14 September 2017. I woke up with a start. It was about 4pm. I was still recuperating, and I was sleeping that afternoon in my room, and someone was shaking me and calling my name. I blinked. I might have started involuntarily. I was in my old home in Umuahia. My parents and other members of my family were there, brothers, nephews, nieces, cousins. We had friends and supporters outside and inside. I had felt safe, secure.

Then I heard the gunfire and I understood what the man standing over me was trying to tell me. I had to get up. I had to get out now. Soldiers had come. They were attacking the compound, shooting, killing my friends and family.

But I refused to go. I suppose for a minute or so I refused to believe what they were telling me: that the soldiers had come to kill me; I would be shot in the head, dumped among my dead companions in a shallow grave on the side of some road. They would say I had resisted arrest. That we had opened fire on the soldiers. That we were to blame. But we had no guns in the house. We only had our voices. And my men had been telling the soldiers they had no right to enter.

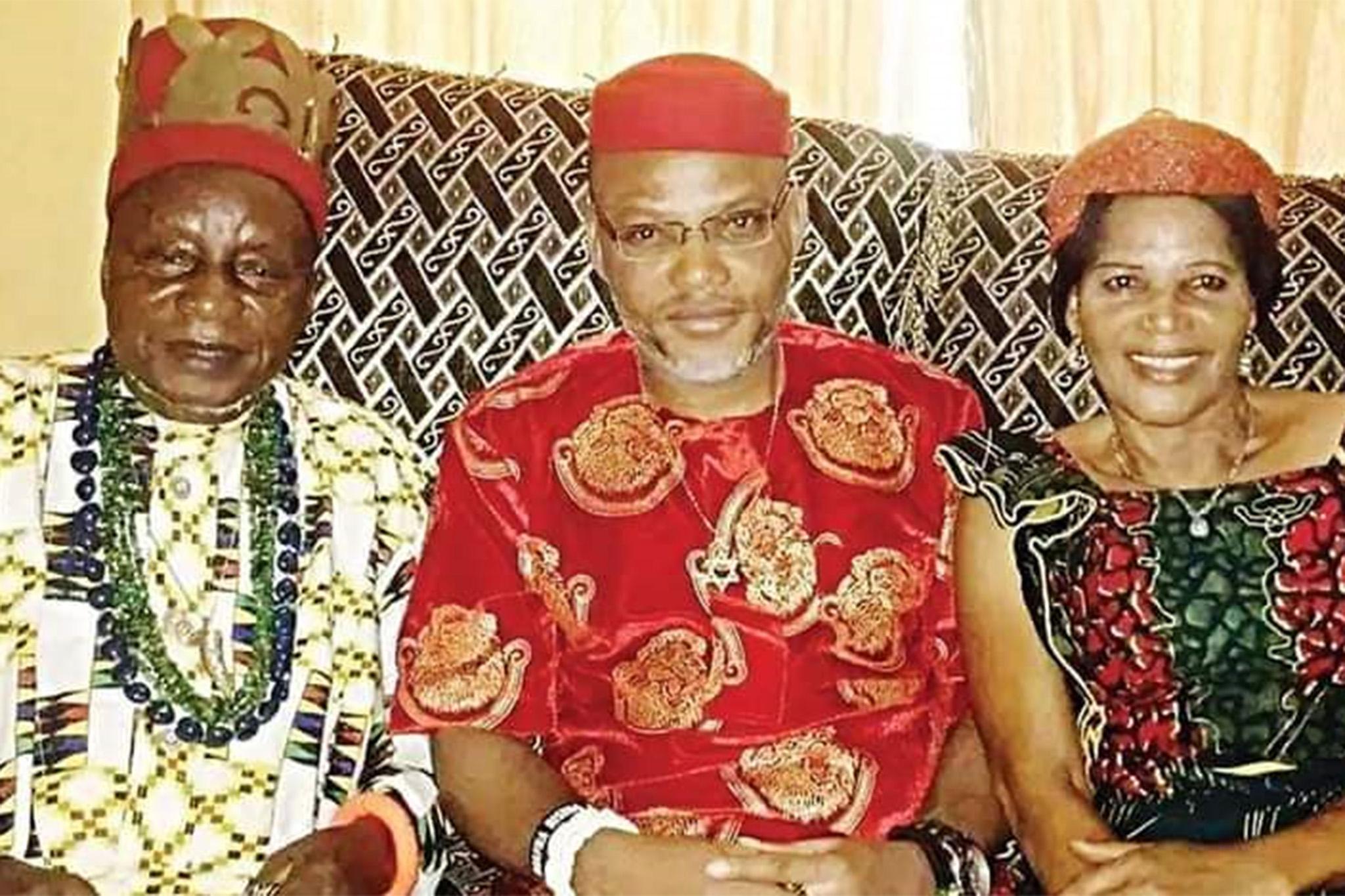

My name is Nnamdi Kanu. I am the leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB). All my life my colleagues and I have been working for Biafran self-determination, the right for the people of Biafra to choose their own destiny, to be free from persecution. You may remember the Biafran war, 50 years ago. In May 1967 Biafra was left with no choice but to secede from Nigeria only to face a vastly superior invasion army and a blockade of food supplies supported by governments as diverse as the UK and the Soviet Union.

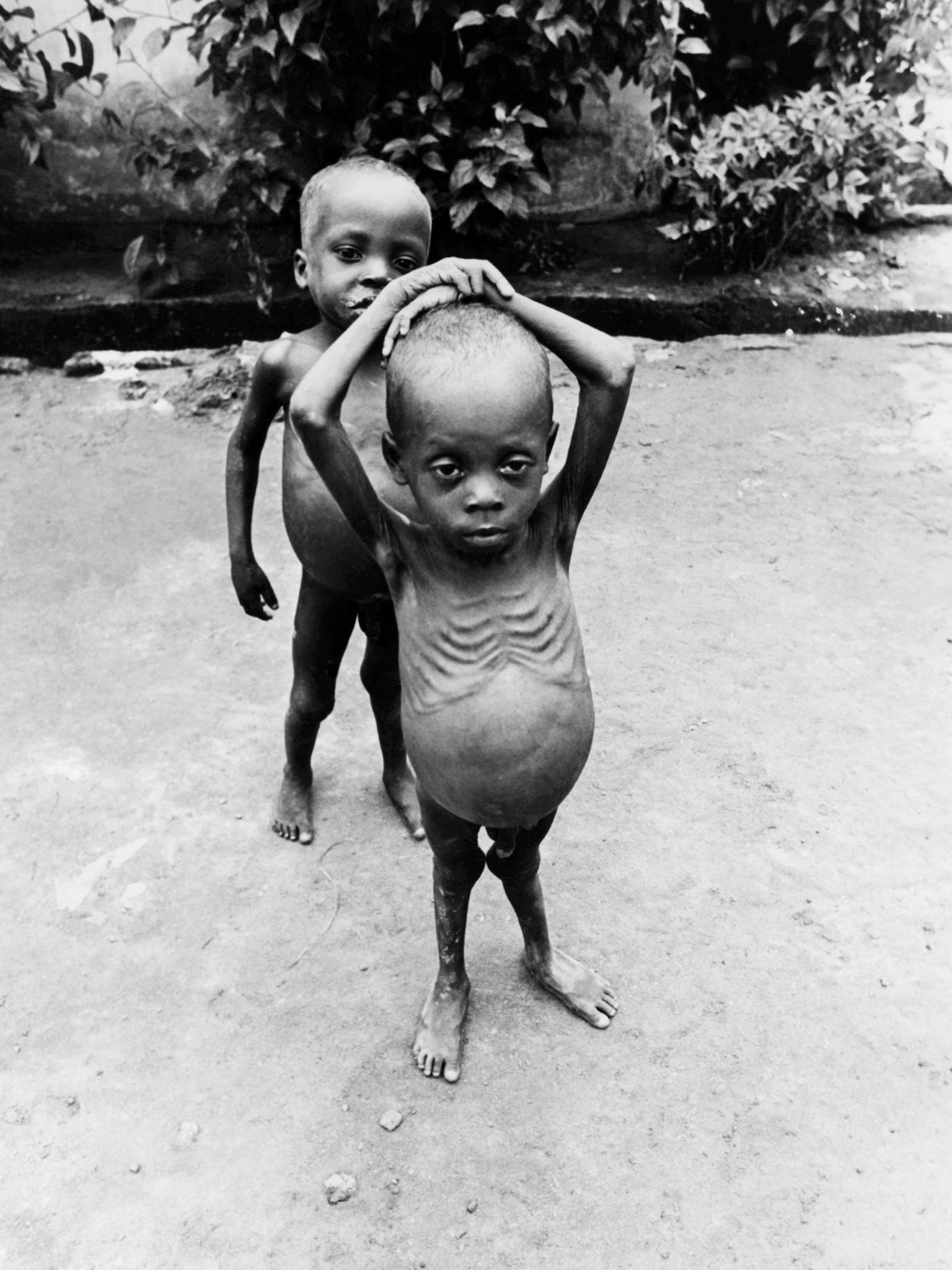

You may remember those photographs of starving children, their bellies distended, crying with hunger, crying without tears because their tear ducts had dried up. Dying mothers, Biafran youth dead on the roads around Port Harcourt. How many Biafrans were killed because of this deliberate policy of starvation has been argued ever since. But it is in the millions. We believe five million. Other estimates are anything between one and eight million. But a handful of adults and children would have been too many, never mind millions.

It was a terrible and inglorious beginning to post-colonial African history. But that was 50 years ago. Now, today in 2019 the violent, brutal persecution of the Biafran people by the Nigerian state and their supporters continues unabated. I will give you facts and figures. I will tell you about the murders, the beatings, farmers driven from their land, young men unarmed except with the flag of our country, shot dead in the streets by those ostensibly sent to ‘protect’ us. I will tell you all these things.

But first… My men began to drag me from the bedroom. I protested. I didn’t want to leave my home. I wanted to confront the soldiers and ask them what they had come for. In just less than a month I had a court hearing. I was determined to be there. My story would be told. The world would know how the Nigerian Security Forces tried to keep me imprisoned without trial on trumped-up charges. How they refused to bring me to court when a judge demanded it. How they ignored the bail that had been posted. How there was still some faint ghost of independence among Nigeria’s judiciary. I would stay for that.

I was being bundled down the stairs and out into the compound at the back, away from the soldiers who had forced their way into the front of the house. My men pushed and pulled me towards the high perimeter wall

Overhead I could hear helicopter gunships, their propellers whirring with that sick, lazy beat they have when they hover. More gunfire. Shouting. Soldiers shouting. My men shouting. I realised the soldiers were not here to arrest me – they could have done that at any time. These were crack troops; they’d called in the air force. They were not here to negotiate my surrender.

I was being bundled down the stairs and out into the compound at the back, away from the soldiers who had forced their way into the front of the house. My men pushed and pulled me towards the high perimeter wall which ran the full circumference of the compound. Ten feet high. Somehow, they man-handled me to the top of this and I fell to the ground the other side.

A sharp, sharp pain literally took my breath away. My limbs flailed. My mouth opened but I couldn’t take in air. I had fallen on my left rib cage. I gasped, convinced that I had punctured my lung in the fall. I heard footsteps and people talking, more gunfire. And always the sound of helicopter blades ripping up the air above me. Then I blanked out.

More than 28 of my fellow IPOB members were killed that day. They had tried to defend my home, my family, without guns, without clubs, only with their bodies and their words. The soldiers even shot and killed the family dog. Initially the Nigerian army denied the assault, but footage and photographs show the attack as it happened and its aftermath.

I wish this had been an unusual day in Biafraland. Violence, harassment and persecution by the Nigerian state and their unofficial militia are constant these days. Biafrans have been persecuted and murdered since before I was born: from the killings of hundreds of Igbo people in Jos in 1945 to the attempted extermination of Biafrans during the war of 1967-70 and modern-day pogroms such as the on-going military attacks on Biafra by the Nigerian Army known as “Operation Python Dance”. Then there is the systematic cleansing of whole areas by Fulani herdsmen from the north. Biafrans have been butchered for reasons that range from religious intolerance, economic incompetence and xenophobic warmongering on the part of a Nigerian state that can hardly keep itself together.

The case of the so-called Muslim Fulani herdsmen from the north of Nigeria, who have already been recognised as terrorists by the international community, is a perfect example of this ongoing persecution. Government policies intended to take land from Biafra and give it to Fulani from the north are driven by a strong undertone of radical political Islam, their objective literally to change the landscape by creating a homeland for the Fulani in the south in order to dominate Nigeria’s political space indefinitely. The People of Biafra and the south of Nigeria are predominantly Christian and Jewish. The Fulani and other people of the north are Muslim. I don’t wish to stoke religious tensions – I am a man of faith and I respect the faith of others – but driving out Christian farmers to settle Muslim herdsmen on their land is not only economic insanity, it is ethnic cleansing.

According to the most recent Global Index on Terror, the first and fourth most deadly Islamic Terrorist organisations in the world operate in Nigeria. Boko Haram is first while the Fulani Herdsmen represent the fourth. More than 1,700 deaths were attributed to the Fulani in the first nine months of 2018. Little is done to stem the flow of violence from either group. The Nigerian army avoids confrontation with Boko Haram and the Fulani enjoy the tacit support of the Nigerian government. Meanwhile, the army is busy attacking peaceful Biafrans under the smoke screen of ‘military manoeuvres’.

What astonishes me, though, is the almost total silence from the world’s media, politicians and the international community surrounding this horrible persecution. The use of Fulani herdsmen to drive farmers from their land, with hundreds of men and women killed in peaceful farming communities in Plateau State and Adamawa and Enugu, documented by the Global Index on Terror and confirmed by Human Rights Watch, ought to be worthy enough of reporting. But we must add the killing and brutal beating by the Nigerian army and police of anyone who supports the Indigenous People of Biafra or calls for Biafran self-determination.

In 2017 Amnesty International recorded hundreds of killings of Biafrans by the Nigerian state. These killings cannot be disputed. The numbers since have not been collated but will be equal. Bodies are buried in shallow graves, thrown in the bush or left on the street. Since 2017 state oppression has included: the beating of young men attending a relative’s funeral in Onitcha in 2019; in August 2018 the arrest and imprisonment in Owerri of 100 women protesting against violence carried out by the security forces and specifically the attack on my home; in 2017 and 2018 brutal beatings given by Nigerian soldiers and police to anyone wearing or carrying the Biafran flag, including a disabled man in Onitsha; the indiscriminate burning down of houses by Nigerian Police in Abia State in October 2019, because their inhabitants support Biafran self-determination.

The Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) that I lead, has one principal purpose: we call for the recognition of the Biafran people’s right to self-determination. We pursue the right to self-determination for Biafrans without the use of force. We uphold human rights. We reject violence. Our successes are measured by peaceful protest, such as the stay-at-home day we have organised on 30 May each year to commemorate the Biafran declaration of independence in 1967.

And yet, despite the violence meted out to us on such occasions, we are called ‘terrorists’ and proscribed by the Nigerian government. No one else in the world has agreed with this move to ban our movement.

In a letter to the president of Nigeria in March 2019, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights declared Nigeria’s proscription of IPOB as a terrorist group and attacks against its members as prima facie violation of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights. The outlawing of IPOB has given the Nigerian government an excuse to send in the army and provided impetus for Islamist militias to drive us from our homes.

Biafra has always been wealthier, better endowed with natural resources and more creative with them than the north of Nigeria. When Nigeria was created in 1914 the stated purpose by then Governor of Britain’s West African colonies, Sir Frederick Lugard, was to marry the rich South to the Poor North and even up the economics of both. It never worked. It only forced together unhappy and angry bedfellows.

The outlawing of IPOB has given the Nigerian government an excuse to send in the army and provided impetus for Islamist militias to drive us from our homes

Almost from the moment Nigeria’s independence was declared, the Biafran people wanted out, which led to the bloody war of 1967-70. Now Nigeria’s government, dominated for so many years by politicians and top brass from the north, has set itself to oppose with full military force peaceful calls for Biafran self-determination. No doubt they hope to stave off the collapse of Nigeria, which commentators from all regions have recognised in recent months.

I came back to my home country in October 2015 to try to help bring an end to the violence and persecution by peaceful means. From London, where I had been living, I had set up Radio Biafra to offer a platform for debate over the right to self-determination of the Biafran people. Because of my activism and vocal criticism of the Nigerian government, I was arrested, demeaned, degraded and treated atrociously and held without trial in an undisclosed location for 18 months.

I was accused of treason and belonging to an illegal organisation. I was denied the bail that had been granted me. And when I was finally released on bail, less than a month before my court hearing, the Nigerian army was sent to kill me as part of its ongoing activities against Biafrans known as Operation Python Dance. So I wouldn’t have a judge decide on my case in a free and open hearing. I wouldn’t be able to expose the attempts by the Department of State Security to silence me. I wouldn’t have the chance to turn the spotlight of the media on to Nigeria itself.

After that terrible day in September 2017, I woke up in a safe house. I was in great pain. My left side was swollen, and every breath was agonising. I had internal bleeding, a doctor told me, and I was advised to rest before I could go anywhere. Then I remembered my parents, my family members who had stayed in the house, young nephews and nieces. I was told they had all congregated in my mother’s room when the soldiers broke in. The room was peppered with machine gun fire.

At the time I knew nothing more. Later on I discovered how, miraculously, no one was killed or badly hurt and the Nigerian army let them be once they knew I was not in the house. But the attack took its toll on my parents. My mother suffered heart complications as a result of the trauma and stress of the Nigerian army’s invasion of my house. She became very ill and died earlier this year. It would not be an overstatement to say that the primary cause of my mother's death was Operation Python Dance 2. I have lost a mother. My father, a strong man, a chief among Biafrans, has lost his life’s companion. Sadly, we have watched his own health decline since the attack on our home and my mother’s death.

I mourn my mother. I mourn all my IPOB family member who had given their lives to protect mine. All those who have been killed since, protesting the actions of the Nigerian security forces in Biafraland. They were brave, good people. They should not have been forced to make that sacrifice, but I will honour them for it until my dying day.

All those who have been killed, protesting the actions of the Nigerian security forces in Biafraland, were brave, good people. They should not have been forced to make that sacrifice

Eventually we were able to rent a boat on the coast. We left from a small town in Abia, Azumiri, an unobtrusive place where the Nigerian authorities might not have thought to look. We planned to go to the Republic of Benin, just west of Nigeria. For 14 days we travelled in dangerous seas in a small boat with an outboard motor. The Atlantic off that coast is heavy, stormy, treacherous. On more than one occasion waves threatened to swamp our little craft. I was still gravely injured and in need of constant medical attention. At one point we put ashore to find ice to keep the medication I needed chilled. It was a dangerous time. I stayed hidden in a room while my companions went foraging for supplies.

From Benin I travelled by road to Senegal, a distance of nearly 2,000 kilometres. Once in Senegal I was able to make arrangements to travel to Israel. None of these journeys was easy. I was still in pain and the threat from Nigerian agents abroad never went away. When we stopped to rest on the road, I couldn’t go out. My world was shrunk to a room with a window, and sometimes not even that. I might as well have been in prison.

Benin, Togo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, all the countries I had to pass through rely economically on Nigeria, their governments corrupt enough to arrest me and send me back. I had to stay silent, unknown. I couldn’t even tell my wife or family where I was, just in case they became targets. It was agonising to realise that they didn’t know if I was dead or alive. Israel was a haven for me, but it took over a year to get there, and only then did I feel confident enough to let my fellow IPOB family members and immediate family know I was safe.

The men who came to my family home in September 2017, came to kill me. I have no doubt of this. If they wanted to arrest me or question me, they would have sent the police or agents of the DSS. Why send soldiers trained to kill, if not to kill? I had wanted my day in court in 2017, but the military response tells me that the rule of law in Nigeria has collapsed. Government agents act with impunity, and I include among them the Fulani terrorists who are doing the Nigerian government’s dirty work, not one of whom has been brought to justice for the murders they’ve carried out.

It is a sign that Nigeria itself is imploding. The old order which has clung to power for decades can only survive at the end of a gun. But even now, if a Nigerian government was willing to talk honestly and openly about our demands and to consider a referendum on self-determination for the Biafran people, in a neutral space provided by the United Nations, I would be there at the table.

Look around Africa today. There are some countries with a functioning democracy, where the rule of law is respected, and free and fair elections allowed. But not Nigeria. Our struggle for self-determination is the struggle of Africa's post-colonisation from Algeria to the Cape. If we can achieve this, perhaps we can lead other African countries to bring democracy and respect for law and human rights into the lives of African peoples.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments