The NME is dead. But its soul left its body long ago

The former bastion of counterculture captured the spirit of punk and in its heyday was uncompromising. Nick Hasted remembers the good times, and charts how the magazine eventually came to embody the sellouts it once excoriated

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.NME was 12 issues from death in 1972. As Nick Kent, the first of its rock writers to studiously resemble a rock star, recalls in his memoir Apathy for the Devil, editors Nick Logan and Alan Lewis were given three months to turn around an out-of-touch pop rag which had had its day. Trawling the similarly dying embers of the hippie underground press, they gave Kent, Charles Shaar Murray and Ian MacDonald their stylistic heads in a final, desperate effort to make the NME matter, in a way it had never managed in its previous 30 years. “I had some cause for self-congratulation,” Kent says, “for I was now strapped mind, body and soul to the whirling zeitgeist of cutting-edge popular culture until I could feel the aftershocks puncturing my very bones.”

The legend of the NME which was forged then, and reinforced by a second influx of writers led by Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons when the paper really found its range by belatedly covering punk, had nothing to do with the publication which gave away its last, brand-saturated copies this week. Though it often fell short, and in its most hallowed 1970s era was capable of now breathtaking sexism and racism, and parlously sub-Hunter S Thompson prose, Kent and co burnt themselves out in pursuit of an ideal.

NME tried to be as important as the music it wrote about. For as long as rock music remained culturally central enough to believe it could change the world, so did NME. Its writers saw themselves as gatekeepers, one of its great 1990s writers, Dele Fedele, once told me. They were holding the line against the sellouts, frauds and incompetents; against anyone who didn’t believe that pop and its hinterlands in politics, cinema and literature could be a radical force for good.

When I bought my first copy as a schoolboy in the winter of 1982, I was so proud I plastered it to my chest as I walked home. I puzzled over its decision to put Jerry Dammers’ new incarnation of The Specials, The Special AKA, on that cover instead of the biggest band of the moment, The Human League, whose singer Phil Oakey was also interrogated by Paul Morley inside. The early-1980s NME’s casual familiarity with postmodern theory and sometimes barely penetrable writing styles was imposing, university-level stuff, but I went with it.

Even as Smash Hits’ nimbler, ironic, colour-packed style half-inched its readers by the thousand, NME remained arrogantly certain of its moral and aesthetic position. It was printed in black, white and grey, suiting the rock noir photos of the likes of Pennie Smith, and the mood of a decade which promised the dole to many. Having previously only known the Daily Mail at home, I got all my politics from NME; at the first sniff of its socialism, which seemed so natural to British rock music then, it changed my mind. That would have been the most fervent wish of its then editor, Neil Spencer, the generally embattled captain of a ship which was again commercially floundering.

As Margaret Thatcher’s election victories throughout the decade proved, NME and its relatively dwindling readership were on the 1980s’ losing side. Smash Hits and its adult, yuppie-friendly offspring Q (an immediate hit in 1986) were for winners. But reading NME every week ensured you knew you were in a fight, and that musicians, writers and readers cared together about its cultural outcome.

Q’s rigorously enforced house style, and the public school-bred, apolitical wryness of its creators Mark Ellen and David Hepworth, were rock journalism’s grim future. But NME was far from finished. Irony and laddishness also infected the paper as it moved into the 1990s under editor Danny Kelly, with the sometimes stifling pretentiousness of 1980s star writers such as Morley now strictly verboten. But it still had room for the romantic rock passion of Gavin Martin (who’d moved from Northern Ireland to write for the paper under punk’s heady influence in 1979, having already inspired a crucial Stiff Little Fingers song with his fanzine Alternative Ulster).

And then there was Steven “Seething” Wells, the shaven-headed, gonzo verbal bruiser who somehow got away with weekly kamikaze assaults on any interviewee who fell short of his fundamentalist, hilarious punk ethos. If he often seemed a thorn in the side of his long-suffering editors as much as his subjects, his complete absence of journalistic balance had its own integrity. Along with one or two other writers such as Stephen Dalton – who approached rock stars with a more conventional gadfly bent – Wells, who died in 2009, was NME’s manic, sometimes irrational moral conscience. Bred in Bradford’s punk poetry scene, he was also its last truly countercultural star writer.

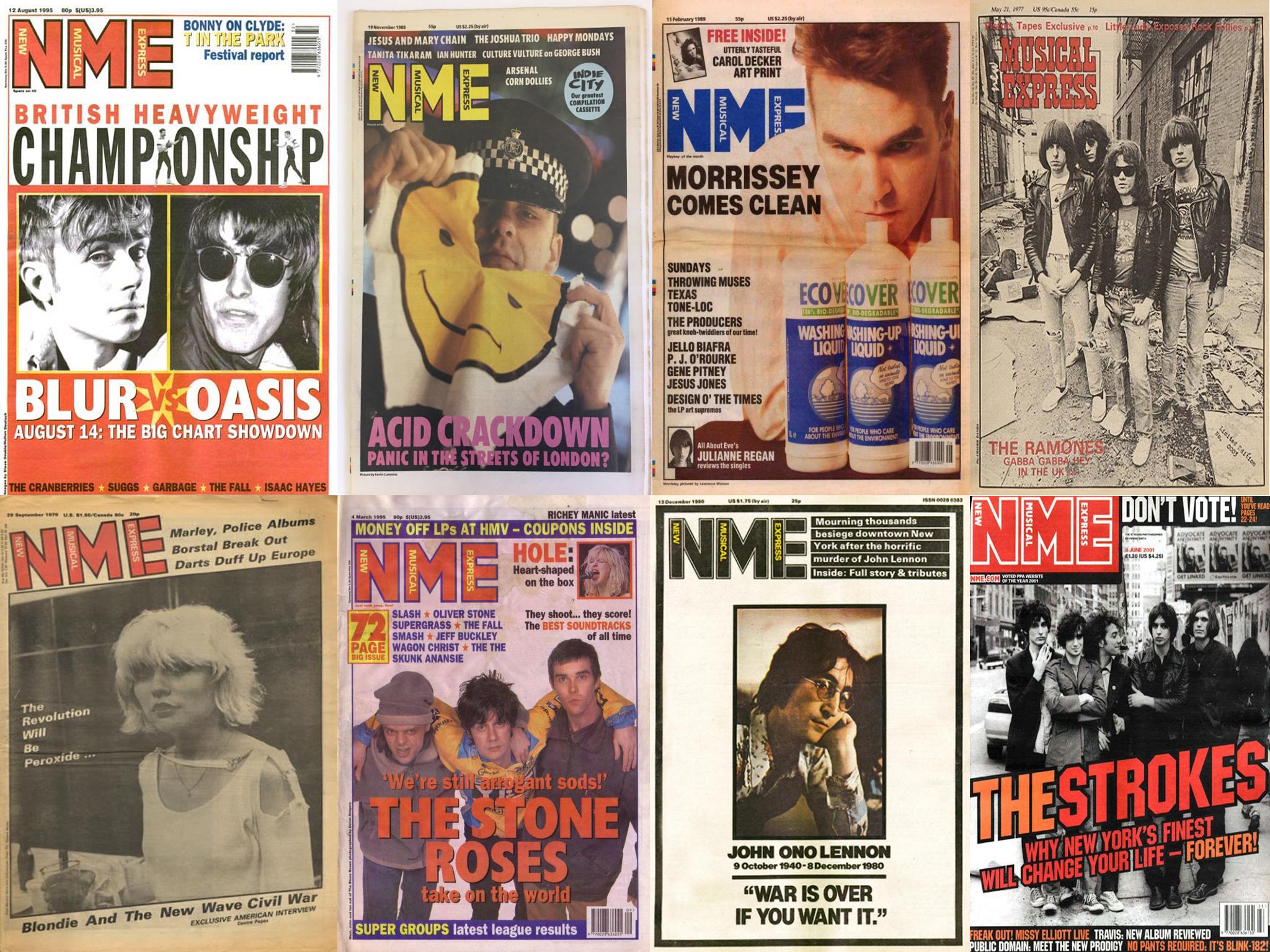

Melody Maker, led by its writer-editors Allan Jones and Everett True, was the rock weekly which really connected in style and attitude to rock’s final global insurrection, 1991’s Nirvana-inspired grunge scene, allowing feverishly personal reportage. NME slipped back to being MM’s more staid rival, as it had been in the 1960s. But NME sold more, and MM was the first to suffer a gruesomely undignified end, futilely chasing the pop market into the gutter to be cancelled in 2000. NME issues such as its 1995 Blur vs Oasis cover, styling (and enflaming) the bands’ nascent rivalry as a boxing promotion, meanwhile made it a thrilling, fervent adjunct to Britpop’s hedonism and hubris.

Both NME and MM maintained more personal relationships with rock stars than is generally possible now. NME’s August 1992 cover story, “Morrissey: Flying the Flag Or Flirting With Disaster?”, was a forensic yet agonised analysis of the singer’s infatuation with skinhead imagery and the Union Jack, which combined with the troubling undercurrents of Morrissey songs such as “Bengali In Platforms” and “The National Front Disco” to suggest a reprehensible side to a man who, till that week, was the ultimate hero of the paper and its readers. The work of several writers including Steven Wells, the investigation and accusation was both morally serious and emotionally fraught.

The fallout between the paper and Morrissey had the bitterness of a divorce. A 2004 rapprochement was merely the prelude to a 2007 story in which Morrissey’s published quotes were again deemed racially inflammatory. The singer sued, claiming inaccuracy, and in 2012 NME apologised if he had been “misunderstood” as racist. This sad, gradual climbdown contrasted with the righteous invective of the 1992 piece, and the sense of mutual betrayal it provoked. NME and Morrissey had mattered intensely to each other.

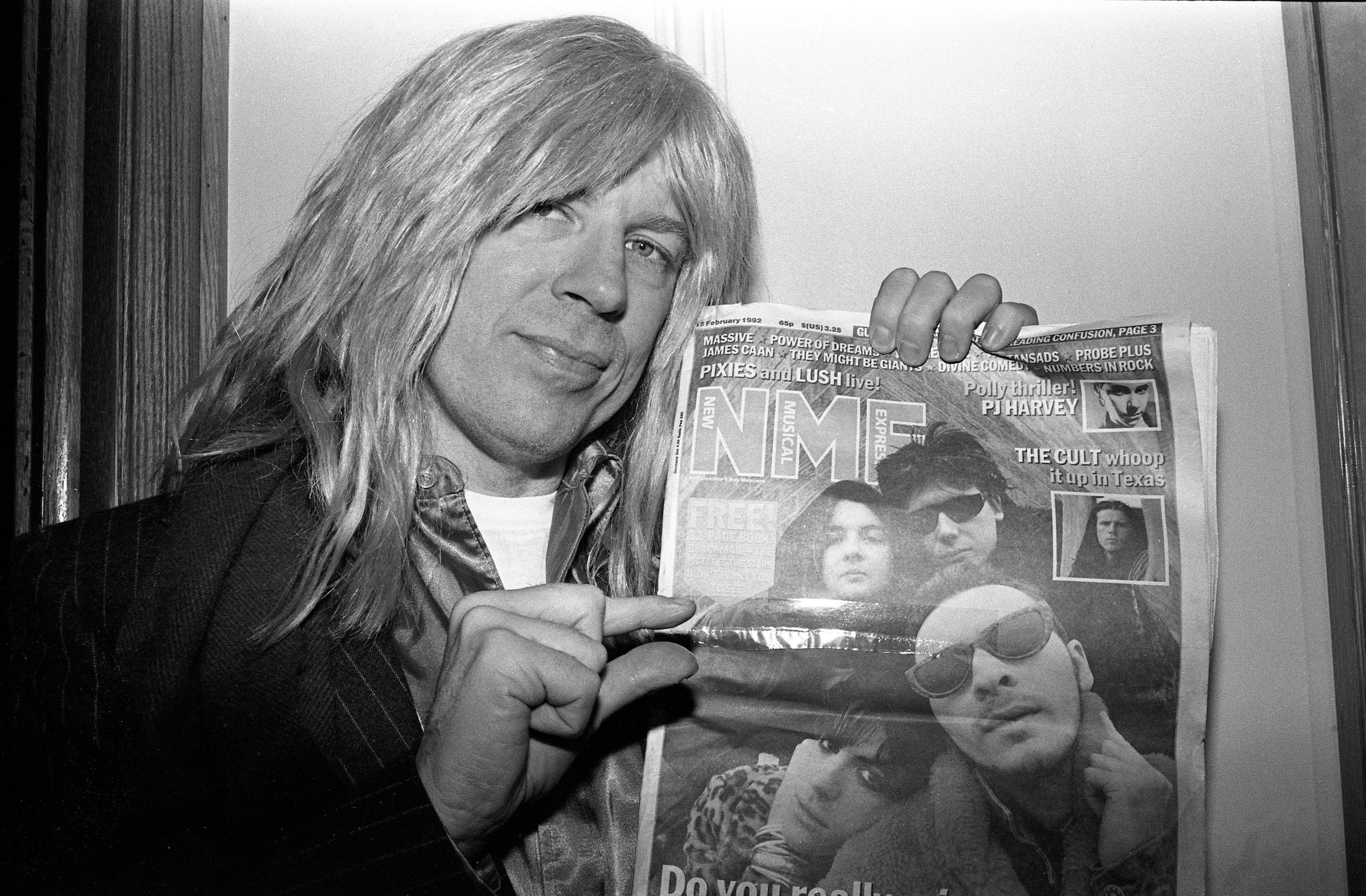

The same could be said for the Manic Street Preachers, whose singer Richey Edwards cut the words “4 REAL” into his arm in front of NME’s Steve Lamacq after a gig, revealing both the extreme state of mind which would later lead to his probable suicide, and how much the doubting writer’s opinion counted to him. The Manics remain devoted scholars of the rock press, and NME in particular.

This intensely symbiotic connection had its final flowering with The Libertines. NME was embedded in the band’s chaotic lives in a way the tabloids who pursued Pete Doherty would never understand. Throughout the 2000s, as the band and fellow travellers such as The Others played impromptu house gigs, battering themselves in the pursuit of a half-glimpsed vision of Albion and incidentally making East London the epicentre of a new, briefly seedy cool, rock’n’roll’s anarchy flowered again. NME writers were once more the scene’s Boswells, faithfully transcribing every overdose and attempt at messy freedom.

There were noble efforts to maintain or revive NME’s spirit into the current decade, even as previously essential elements such as the Gig Guide and gig and album reviews were diluted; deemed irrelevant in the new digital reality. The failure to ever really expand beyond the conservative indie-rock constituency which The Smiths had helped forge didn’t help. But the ghost, anyway, finally left the print body when it went free.

“The print reinvention has helped to attract a range of cover stars that the previous paid-for magazine could only have dreamed of,” publisher Time Inc’s UK group managing editor declared this week, with perhaps unconscious irony. Time, like NME’s former publisher IPC, never understood what it had. And only in its contributors’ most unlikely, sweat-soaked nightmares would the old, real NME have contemplated covers like the last one I picked up. It promised a new, revolutionary movement. Picking through the pretty vacant quotes of the musicians chosen to embody this new dawn, though, it became clear that the “revolution” was by a clothing company. Many of the pages were unstated advertorial. The paper which once accused musicians of selling out couldn’t have done so more completely.

The largely retrospective rock monthlies which have replaced NME exist in a commercial world where its old, oppositional ethos is deemed impractical. Bad reviews of major artists tend not to happen. Kamikaze interviews are not countenanced. One of my own employers, Classic Rock, still gives writers their head, and seeks their forebears’ glamorous, riotous, journalistic elixir. But NME’s spirit continued most completely in The Stool Pigeon, a briefly brilliant free paper in the old, inky broadsheet format which still smelt of a broader underground, and cared enough about the music it wrote about to satirise and undercut it, before it too shut down, defeated. The online publication The Quietus now holds music’s moral line, operating on a shoestring and a prayer.

NME itself has been on undignified life support for far too long, begging for a mercy killing. Formerly loyal readers passed by its piles of free copies with the embarrassment of glimpsing an old friend on hard times, and new, young readers never bought print in the first place. The NME website may maintain its brand in perpetuity, but the ideals which gave that brand its potency bled out long ago.

Rock and rock journalism have dwindled in cultural currency together over the past 20 years, and NME’s extinction is a no-longer-significant symbol of that. The music still matters as much as ever, though to many less people: still saving and changing lives, still a grail worth pursuing. It’s the music papers that got small.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments