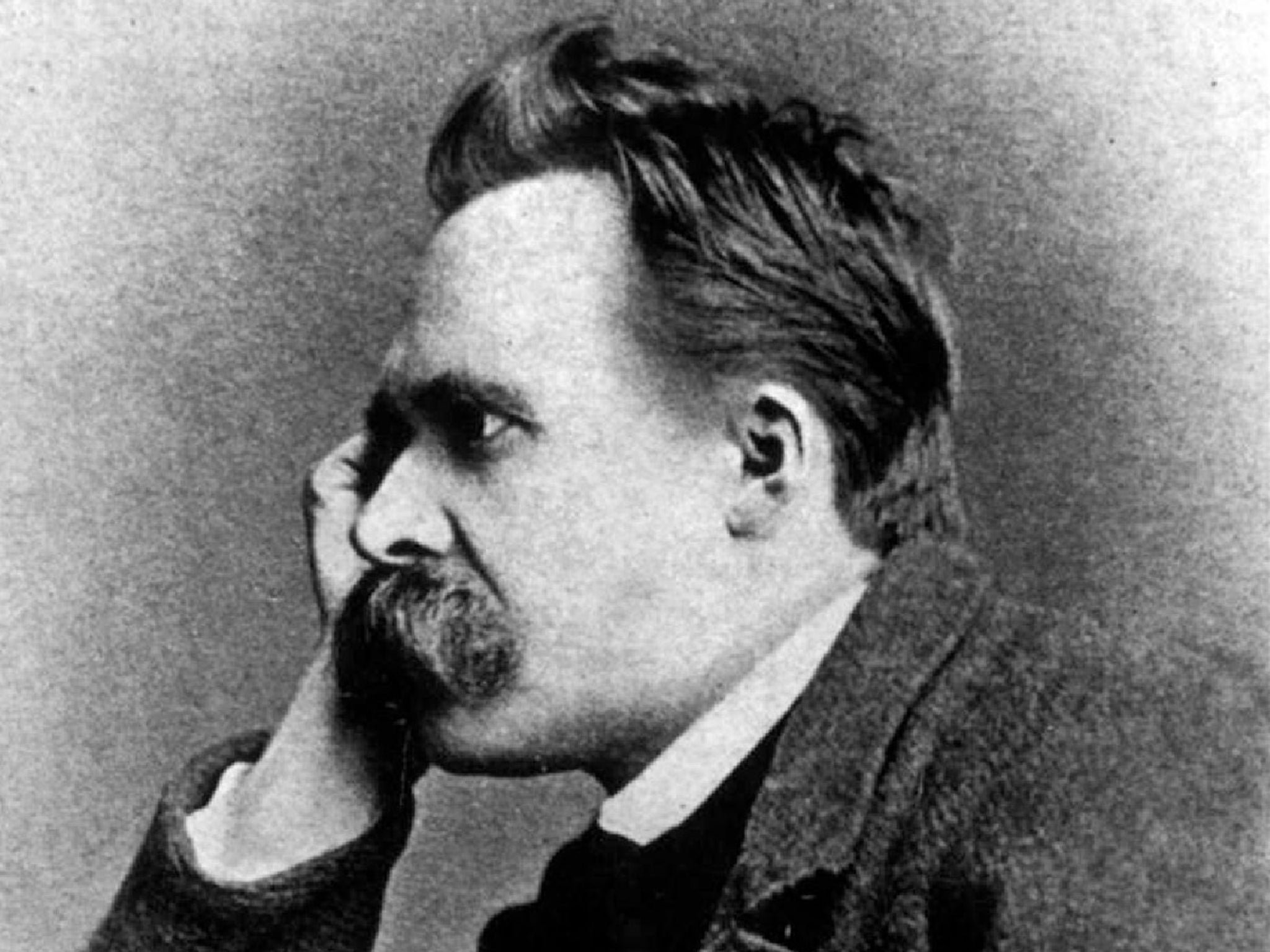

In defence of slavery: Nietzsche’s dangerous thinking

Artists, adolescents, and assorted free spirits venerate him as the prophet of total liberation. But Nietzsche did not think all should be free. Martin A Ruehl reveals a disturbing and politically incorrect aspect of the great philosopher

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He thought of his own views as “untimely” and called himself “the last anti-political German”. In his hero-worshipping autobiography Ecce Homo, he claimed he was “born posthumously”. Nietzsche scholars and admirers have taken these statements at face value. For them he is a philosopher out of time, wholly detached from the socio-political affairs of his era.

When Friedrich Nietzsche glorifies war, domination, and cruelty, they tell us he is speaking of a “spiritual” struggle, and the merciless suppression of everything that is weak or “resentful” within ourselves. An outspoken critic of German nationalism, Nietzsche was completely at odds, we are told, with the prevalent political ideologies and preoccupations of the day.

But a note in his unpublished papers, known as the Nachlass, casts doubt on these apolitical readings. In a topical entry from 1884, he condemns the emancipatory movements that were transforming Western societies in the 19th century. Nietzsche lists their objects with palpable disdain: women, slaves, workers, “the sick and the corrupt”. The fragment leaves little doubt that its author considers the emancipation of these groups a disastrous mistake bound to exacerbate the “levelling of European man” and the decay of contemporary European culture.

Nietzsche blames the modern demand for democratisation on the rhetoric of the Enlightenment, and especially on the “seductive” concept of universal human goodness propounded by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He holds Rousseau’s moral fanaticism responsible not just for the French Revolution, but for virtually all the egalitarian and humanitarian politics since then.

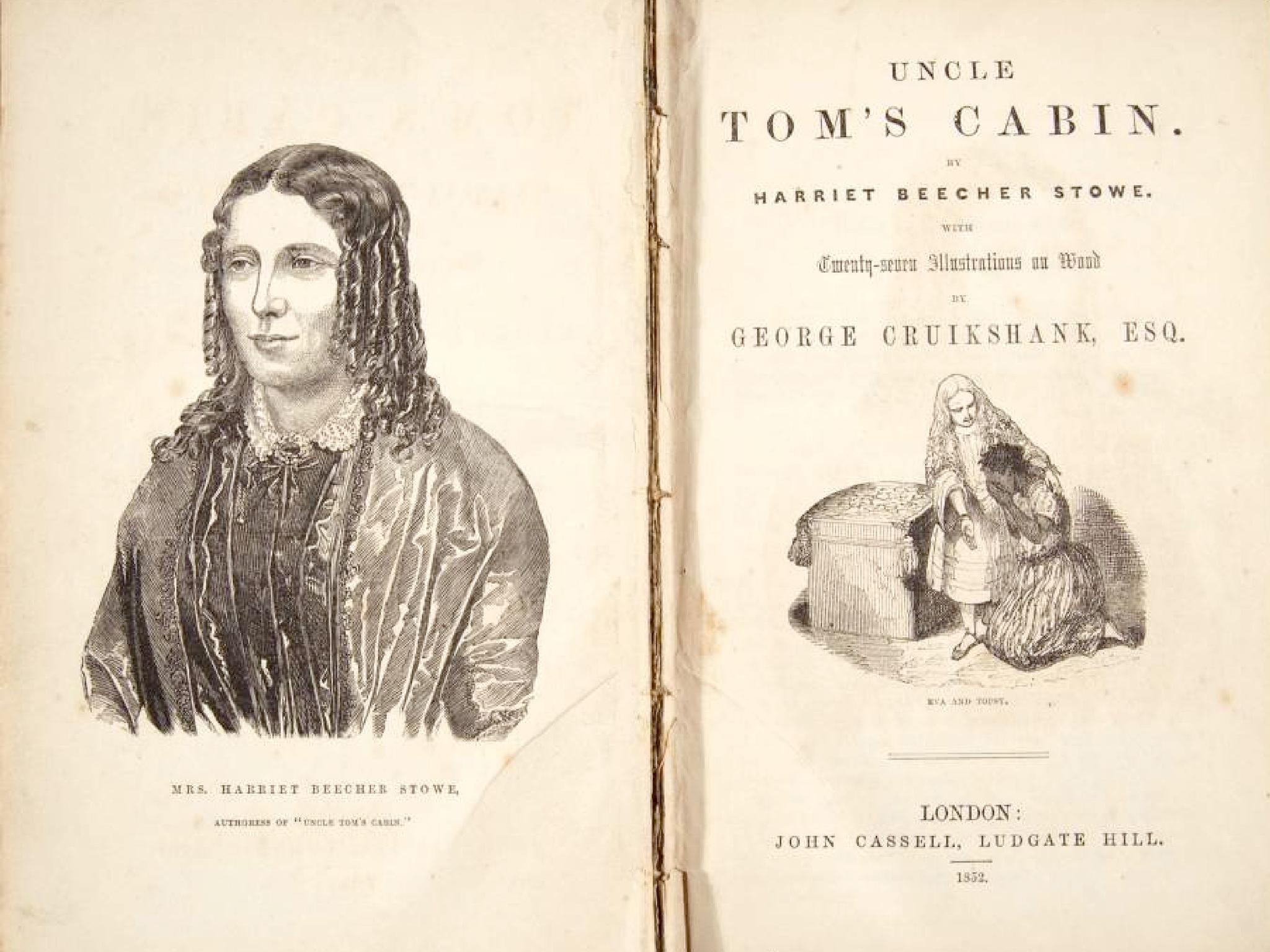

When he turns to the emancipation of slaves, however, Nietzsche mentions another name: “Mistress Stowe”. He is referring to Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of the famous anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, first published in 1852 and translated into German the same year.

By the time Nietzsche jotted down his anti-emancipatory musings, Uncle Tom’s Cabin had run through no fewer than 50 editions in Germany and prompted countless reviews – almost without exception positive – in German journals and newspapers. In denouncing Beecher Stowe as a deluded follower of Rousseau’s false gospel of man’s natural goodness and equality, Nietzsche was taking a decidedly unpopular position in the political landscape of late 19th-century Germany.

His reference to Beecher Stowe in the 1884 fragment is significant for a number of reasons. To begin with, it reveals his familiarity with the debates about abolitionism in America, which adds an important transatlantic context to his reflections on masters and slaves and his profound, abiding belief in human inequality.

In 1864, at the height of the American Civil War, the 19-year-old Nietzsche submitted a valedictory thesis on the Greek poet Theognis of Megara. Extremely learned and at the same time subtly partisan, it was a sympathetic reconstruction of Theognis’ staunchly aristocratic world view, including his racist, segregationist views on forced labour. Slaves, Nietzsche remarked, hailed from “useless and harmful stock” and belonged to an altogether different and invariably subordinate species. Approvingly he cites Theognis’s “very accurate” poem:

Never do the enslaved go upright

But the crooked necked are ever gnarled

Just as a squill does not bear roses or hyacinths

A slave woman does not bear a free child.

These comments echo the arguments of Southern apologists of slavery like William Harper, who insisted on the inherent physiological and psychological differences between Africans and Europeans. In his Memoir on Slavery, Harper maintained that “the Negro race, from their temperament and capacity” were “peculiarly suited” to hard labour, not least because they were significantly less susceptible to physical pain than white men. Nietzsche was convinced that Africans, whose constitution he believed closely resembled that of “primeval man”, felt less pain than white people, especially the white “cultural elite”. In Daybreak he pondered the possibility of importing Chinese workers to Europe to carry out menial tasks, because their “modes of life and thought” made them suitable “industrious ants”.

Like George Fitzhugh, the South’s preeminent pro-slavery theorist, Nietzsche frequently invoked Ancient Greece to argue that slavery belonged to “the essence of a culture” and that in order for there to be a “fertile soil for the development of art”, the “overwhelming majority” had to be “slavishly subjected” in the service of a “privileged class”.

In stark contrast to most German philhellenists, including his own one-time friend, mentor, and artistic model Richard Wagner, Nietzsche believed that slavery was the sine qua non of the cultural glory that was Greece. Even if it were true that the Greeks had been “ruined because they kept slaves”, he mused, “the opposite is even more certain, that we will be destroyed by the lack of slavery”.

This certainty, however, had become obscured by contemporary liberal notions such as the “dignity of life” and the “dignity of work”. In his unpublished essay on “The Greek State” (1872), Nietzsche tries to do away with these notions. The most salutary lesson to be learnt from the Greeks, he writes, is that “man as such” possesses “neither dignity, nor rights, nor duties” and that work is little more than “a necessary disgrace”, of which one ought to feel “ashamed”.

His critique of liberalism here reiterates that of Fitzhugh, who had argued that the free-market economy of the North by no means provided its workers with a more dignified or humane existence than the Southern plantation. Nietzsche, too, sees new forms of dependence and servitude lurking behind the facade of “free labour”. The modern industrial worker has become a mere cog within a “mechanical operation”, a human being reduced to a thing owned by someone else. Capitalism, he observes in Daybreak, amounts to “impersonal enslavement”.

If Nietzsche’s reference to Beecher Stowe highlights the transatlantic context of his ideas, it also underscores their fiercely anti-modern political dimensions. The latter are all too conveniently glossed over by those who hail Nietzsche as a quintessentially modern thinker.

Turning him into an intellectual precursor of the great cultural and philosophical movements of the 20th century, from expressionism and surrealism to existentialism, they have isolated him from his own time, with its very distinctive prejudices and preoccupations. These “gentle Nietzscheans” overlook his passionate opposition to the socio-political values and institutions of modernity, and the counter-revolutionary implications of his revolutionary ideas. Praising him as a champion of (self-) liberation, they ignore the severe restrictions he places on the idea of human emancipation.

A closer look at Nietzsche’s views on slavery would bring these restrictions into focus. Yet in the vast and steadily increasing body of literature on Nietzsche (no other philosopher has attracted more commentaries), there is not a single in-depth study on this topic, even though slavery is a recurrent theme in his writings, from his valedictory thesis to the very late works, completed weeks before his mental collapse in January 1889.

There are more than 300 references to slaves, slavery and similar terms in Nietzsche’s works. The vast majority of these affirm the necessity of human bondage.

In Beyond Good and Evil he wrote: “Every enhancement of the type ‘man’ has so far been the work of an aristocratic society – and it will be so again and again – a society that believes in a long scale of orders of rank and differences in value between man and man, and that needs slavery in some sense or other.”

Throughout his oeuvre, Nietzsche adheres to the view that slavery was, is, and will be needed: for the flowering of Ancient Greek civilisation; for the regeneration of contemporary European culture; for the establishment of a new nobility based on a new social “rank-ordering”; and for the future elevation of “man” into “superman”. Nietzsche consistently formulates his most radical ideas about human flourishing and autonomy in the context of their opposites, what he calls “the danger of servitude” and the “incomplete” humanity of the slave. But slavery, for him, is less a foil to than a condition of human greatness. In The Gay Science, he significantly mentions “subhumans” as the natural attendants of heroes and supermen.

Almost without exception, Nietzsche scholars have either ignored his pro-slavery comments or urged us to read them metaphorically. Political theorists eager to claim him as a champion of radical democracy have tiptoed around them. As a result, one of the most singular features of Nietzsche’s thinking remains virtually unexamined, and we still have to account for his peculiar status as the only modern philosopher to fundamentally reject the principal credo of modernity, namely that all are created equal and have an inalienable right to liberty.

The failure of the experts to tackle Nietzsche’s defence of slavery has come at a cost. It has left us with an impoverished understanding of his moral and political philosophy, central concepts of which – “master morality”, “aristocratic radicalism” and “discipline” – are closely tied to his ideas about slavery. It also prevents us from appreciating the full force of his critique of liberalism and socialism, both of which Nietzsche regards as products of the grand Enlightenment narratives of progress and emancipation, or of what he calls the “siren songs ”of “equal rights and a free society”.

Among other things, Nietzsche’s justifications of slavery, notably his advocacy of “natural slavery”, provide us with a new perspective on his conception of human nature and psychology. As he writes in Beyond Good and Evil, slavery is the “prerequisite for spiritual discipline and cultivation”, a “moral imperative of nature” addressed to “peoples, races, ages, and classes – but above all to the whole human animal, to man.”

To read Nietzsche’s reflections on slavery historically does not mean to read them literally. Contextualising them, however, reminds us that slavery in the last third of the 19th century was more than a metaphor for lack of individual sovereignty or self-determination. It was a pressing and very current issue, fraught with political and ideological controversies, notably about the rise of capitalism and the so-called social question, but also about race, empire, and the West’s self-proclaimed “civilising mission”. If we approach Nietzsche’s philosophy in this way, we allow it truly to challenge our liberal, humanist assumptions. That would make his “dangerous thinking” even more dangerous.

Martin A Ruehl teaches German intellectual history at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments