What if Nick Clegg had gone into coalition with Labour, not the Tories, in 2010?

As we approach another point in our country’s history when the choices made by a few will be momentous, John Rentoul reimagines one of contemporary politics’ biggest hinge moments

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In an alternative universe, Emily Thornberry, the country’s second female prime minister, has just unveiled her plan for a Green, Social Europe, with Britain at the heart of it. Still enjoying a honeymoon with the public after her victory in the 2018 general election over Michael Gove’s confused and Eurosceptic Conservatives, Thornberry rounded on “prominent people in British politics, in parliament and out of it”, who want to reverse the result of the EU referendum.

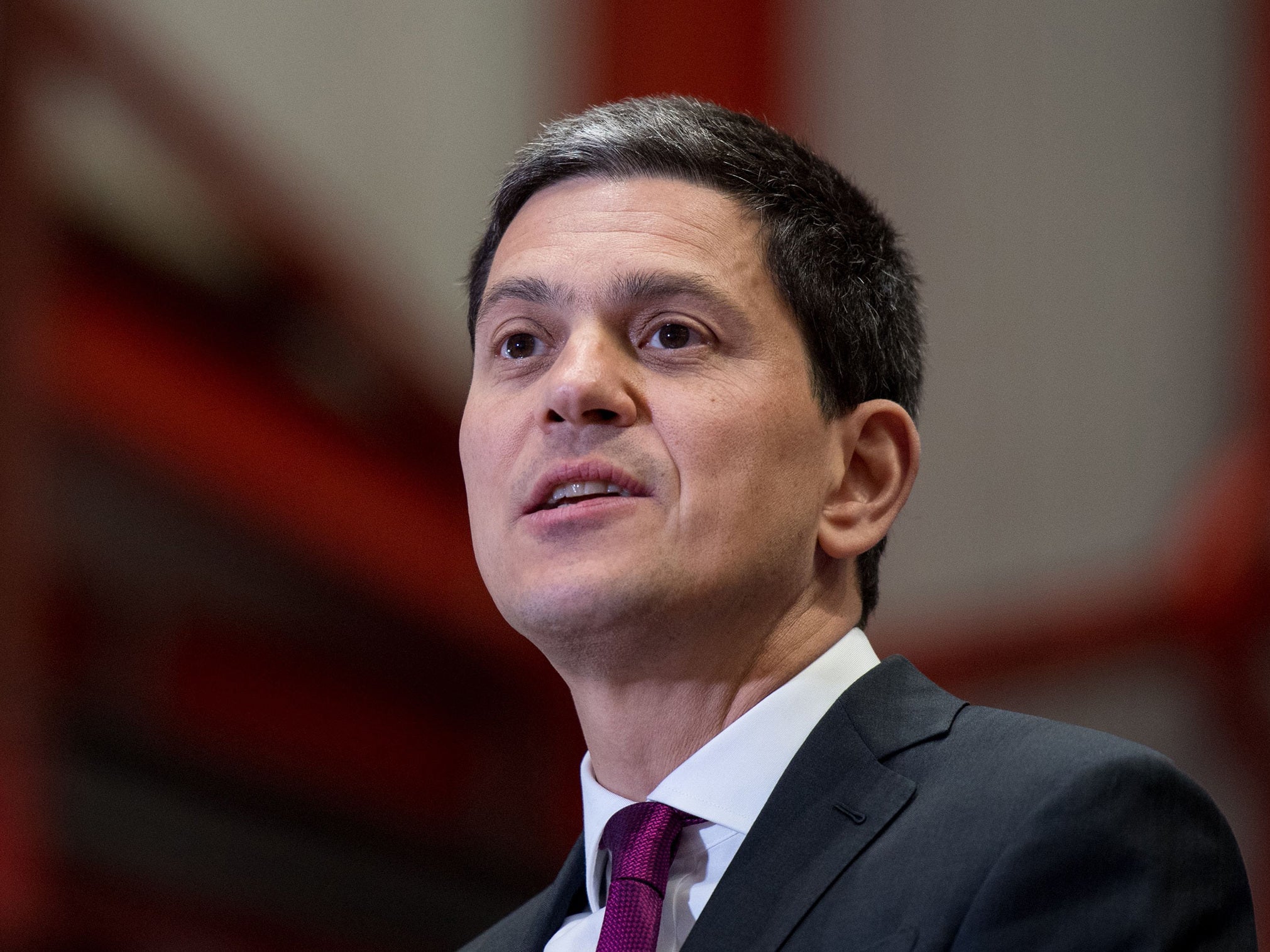

Speaking at a rally of the Movement for Change, the group set up by David Miliband, the former prime minister, which was now the party’s biggest left-wing pressure group, she said: “Their latest plan is to hold a second referendum. They call it a ‘people’s vote’. But we had the people’s vote. The people voted to stay.”

How did we get here? Let me take you back to a hinge moment in British history: to May 2010, when Nick Clegg and the Liberal Democrats faced a big choice. Should they throw in their lot with the Conservatives or with Labour? It was quickly assumed that a deal with the Tories was the obvious choice, and now it is more or less forgotten that there was another option. It would have been more difficult, but if the Lib Dems had gone with Labour there would have been a clear anti-Conservative majority in parliament. A Labour-Lib Dem coalition would have been perfectly possible if Clegg had wanted to make it work.

So what would have happened if Clegg had stuck with the economic policy he and Vince Cable advocated during the election campaign, which was closer to Labour’s less stringent plan for deficit reduction than the Tories’? What if Gordon Brown had recognised straight away that he was an obstacle to a deal and had agreed to go, and what if David Miliband had seized his moment to declare that he would seek the leadership?

Although Labour fatalism helped put the Tories in office, the critical determinant was Nick Clegg’s instinct to go right rather than left

Andrew Adonis, the transport secretary in the House of Lords, advising Brown as he was holed up in 10 Downing Street after the election, felt strongly that a deal between Labour and the Lib Dems should have been struck. He wrote a book about the negotiations, Five Days in May, in which he blamed three people for their failure: Clegg for being a closet Tory; Brown for taking too long to realise he would have to quit; and Miliband – and much of the rest of the Labour Party – for lacking the “will to power”.

Adonis wrote: “Although Labour fatalism helped put the Tories in office, the critical determinant was Nick Clegg’s instinct to go right rather than left.” What, then, if that instinct had been to go the other way?

Adonis insists to this day – and I agree with him – that too many Labour people looked at the election result and concluded that “the numbers were not there”. But Labour’s 258 seats plus the Lib Dems’ 57 and the three MPs of Labour’s sister party in Northern Ireland, the SDLP, would have been 318 seats against 315 for the Conservatives and the DUP combined. In addition, there were a further 12 MPs in that parliament, all of whom would normally vote with Labour. The Scottish and Welsh nationalists (six and three MPs respectively) and the Green (Caroline Lucas) were strenuously anti-Tory, while Northern Ireland MPs Naomi Long (Alliance Party) and Sylvia Hermon (independent unionist) were more even-handed but also Labour-leaning.

Adonis wrote: “Had Gordon resigned the Labour leadership immediately on the Friday morning, and announced that he intended to take no role in a Lab-Lib government apart from negotiating its birth, this might have made it harder for the Lib Dems to go into coalition with the Tories.”

I have been reminded of those days by the publication of the latest volume of the Alastair Campbell Diaries, covering his time as a half-in, half-out adviser to Gordon Brown from 2007 to 2010. Like Adonis, Campbell wanted to keep Labour in government. He recounts how Brown decided to announce, on the Monday after the election, that he would stand down by the autumn if Labour and the Lib Dems could agree a deal. Indeed, he reveals that Brown had thought about pre-announcing his departure in one of the leaders’ TV debates during the election campaign, but had decided against it.

Campbell also says that on the Sunday after the election David Miliband had sent him a text saying “he didn’t believe a second unelected PM was possible”. Brown had been sensitive to the charge that he had taken over from Tony Blair without a general election, and Miliband thought it would look undemocratic for it to happen again, especially so soon after an election.

Adonis and Campbell took a more robust view of the British constitution. Anyone can be prime minister if they can command a majority in the House of Commons – and there was no doubt that, if the Lib Dems had gone the other way, whoever was Labour leader would have been able to form a government.

Unfortunately for Labour, Clegg had made this harder by saying before the election that he would talk first to whichever party won the most seats. There was no precedent for this, which Adonis took as further evidence of Clegg’s pro-Tory bias.

As it turned out, a coalition with the Conservatives looked simple, and would have a large majority over all other parties – although at the time it was considered such a bad ideological fit that many people expected it to collapse before long. Labour and the Lib Dems, on the other hand, agreed on many more policies, and most Lib Dems would have preferred to work with Labour.

Let us play the alternative history game, then. I would argue that such moments show that individuals do matter. If Clegg had made a different choice, we would be living in a different country now: slightly better off, with better public services, and probably still in the EU.

Let us imagine that Brown, having announced he would be stepping down as Labour leader and prime minister as soon as a successor was elected, formed a government, with Clegg as deputy prime minister.

In the garden of No 10, journalists were amazed by how well Brown and Clegg appeared to get on, joking at each other’s expense, as they announced a referendum on the voting system. Four Liberal Democrats joined the cabinet, and trouble was predicted from the four Labour ministers who had to make way for them.

In the next few days the coalition agreement was hammered out, including a Fixed-term Parliaments Act prescribing four-year parliaments and setting the date of the next election as 2014. (George Osborne’s last-moment change to five-year parliaments did not happen.)

Brown and Clegg even signed memorandums of understanding with the DUP, SNP and Plaid Cymru, promising extra public spending in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and the vote on the Queen’s Speech setting out the coalition’s programme was carried by a comfortable majority of 28.

When it became clear that the coalition would not collapse immediately, David Cameron resigned as Tory leader and the two main parties held parallel leadership elections over the summer. Cameron was replaced by Liam Fox, who committed the Conservative Party to a referendum on membership of the EU, after a future Tory government renegotiated terms.

David Miliband, the foreign secretary, narrowly beat his brother, the energy secretary, in the Labour contest and took over as prime minister in September, surprising everyone by appointing Ed Balls as chancellor. Ed Miliband became foreign secretary with special responsibility for climate change agreements.

The referendum on the Alternative Vote system was narrowly lost in 2011. Prime Minister Miliband was blamed for failing to support change enthusiastically enough. Still, Clegg won a consolation prize for his party by replacing the House of Lords with a second chamber called the Senate, elected by proportional representation. (Footnote for election system nerds: members elected for 12-year terms by an open list system in European parliament constituencies, starting to be phased in at the 2014 election.)

David Miliband struggled to connect with the general public – he was booed at the 2012 Olympics – but gained a reputation as a smart and effective operator. He outplayed Alex Salmond, for example, by agreeing that the Scottish government could hold a referendum on independence in 2013, which “No” won 60-40.

Generally, the Lib-Lab coalition held together surprisingly well, and Clegg, who had got on badly with Brown, found working with Miliband – only two years older than him – a huge relief.

There was a bad moment when the Lib Dems and SNP combined to force a full independent public inquiry into the British role in torture, which Miliband regarded as a personal attack on him. But for most of the parliament the Lib Dems struggled to differentiate themselves from Labour. Clegg tried civil liberties, the living wage, climate change and a crusade against “vulture capitalism”. Each time he was outdone by Miliband, who found many of these left-wing poses surprisingly popular, and the Labour government took most of the credit for what it claimed was a programme of “radical” reform.

Even so, Labour Party members were mutinous about “austerity”, forcing Balls to insist that his policy was expansionist and to stress the dividing lines between it and the “slash and burn” policy advocated by his shadow, Michael Gove. And there was growing hostility among the wider electorate to Britain’s membership of the EU and the free movement of people it entailed. Miliband was accused by the Eurosceptic press of failing to “get” popular discontent with the ambitions of an EU superstate.

Meanwhile, Liam Fox was criticised by many Tories for the narrow and xenophobic tone of his campaign for better terms of EU membership, and was accused of secretly wanting Britain to leave the EU altogether. Many felt that a more centrist campaign for an EU referendum would be more effective.

The question of the Tory leadership was electrified when Boris Johnson stood down after one term as mayor of London, and re-entered the House of Commons in the Corby by-election in November 2012, a vacancy created when Louise Mensch left for New York.

When Fox resigned over an incomprehensible scandal the following year, Johnson easily defeated the unknown Andrea Leadsom to become leader of the opposition. With real wages stagnant after falling for several years, and Labour having been in power for 17 years, Miliband tried to relaunch his government with a sharp but not wholly convincing turn to the left. But Johnson’s programme of social Toryism plus Euroscepticism proved more popular, as he promised to raise spending on health, education and policing – and said he would not reverse Miliband’s nationalisations.

Thus a suddenly serious Johnson came to power in the general election of 2014 – he looked as if he had lost on the morning after the vote – with a tiny majority and a promise of a referendum on EU membership. The election was followed by European parliament elections in June, in which the Tories swept the board. Ukip, having lost all its seats, wound itself up.

Johnson brought in a registration scheme for immigrants from the rest of the EU, and negotiated token reforms to the terms of UK membership in Brussels, eventually holding a referendum on 23 June 2016. Prime Minister Johnson led the “In” campaign – the Electoral Commission rejected a bizarre plan to use the words “Leave” and “Remain” as the options on the ballot paper. Theresa May, who had been catapulted surprisingly to home secretary after the election, led the “Out” campaign, in partnership with Michael Gove, the chancellor.

“In” won the referendum by 52 per cent to 48 per cent and May immediately launched a campaign for another “people’s vote”, claiming the “In” campaign had lied and outspent the “Out” campaign by two to one.

Johnson was unable to contain the divisions in the Tory party and was brought down by Gove shortly before the 2018 election, which was won comfortably by Labour under Emily Thornberry.

Which brings us to the present: Prime Minister Thornberry has just addressed the rally of left-wing Labour members – some of whom, I am sorry to say, booed her. They refused to forgive her for supporting Miliband’s Great Left Turn, which they derided as “putting lipstick on the capitalist pig”.

There is a serious point to these frivolous speculations. Because Thornberry, in combative form, could have said to her hecklers: “Imagine if we had had a Tory government for the last eight years, instead of just the last four. Imagine the damage done by Boris Johnson, doubled. Imagine a recession made worse by the cuts Cameron and Osborne had planned eight years ago. Imagine if people had reacted to that deeper, longer austerity by voting to leave the EU. Then the country would look very different today.”

Politicians don’t often make those kinds of speeches, because what’s gone is gone. But if Nick Clegg had made a different decision in 2010, the country could be quite dramatically different today. Maybe better in some ways, although different mistakes would surely have been made. He might even still be MP for Sheffield Hallam rather than publicity flack for Facebook.

Adonis is right that individuals do shape history. Maybe not Clegg alone; it may have needed Gordon Brown and David Miliband or Alan Johnson to have made different choices too. But if just Clegg alone had reacted differently, perhaps that would have influenced them.

More controversially, I tend to provoke a furious reaction from Jeremy Corbyn’s supporters when I point out that, if Labour and the Democratic Unionist Party had done a deal after the 2017 election, we could have a Labour government now. After all, Labour did a deal with Ulster unionists in 1977, which kept James Callaghan in power for two years. Brown spoke to the DUP before and after the election in 2010, and Ed Miliband had discussions with them before the 2015 election. Labour supporters tend to regard the DUP’s policies, especially on gay rights, as peculiarly abhorrent, but is a Labour government rather than a Conservative one not a greater prize?

We are approaching another point in the country’s history when the choices made by a few will be momentous. No one knows how Brexit is going to end, and it may be that those with the clearest vision and the greatest determination will make history. The nation’s future could even be decided by the vote of a single MP if there are close votes in the Commons.

If there is a lesson from history, it is that those who find themselves in a position to make big binary decisions should not allow themselves to be trapped into thinking the less obvious choice is too difficult. If it is possible, it might be worth a try.

Andrew Adonis, ‘Five Days in May: The Coalition and Beyond’, published by Biteback, 2013

Alastair Campbell, ‘From Crash to Defeat: Diaries, volume 7, 2007-2010’, published by Biteback last month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments