Sandman: The ‘unfilmable’ Neil Gaiman masterpiece that made comics cool again

A Netflix adaptation of the 1980s graphic novel – which united hardcore geeks and first-timers alike – is on the cards after several false starts. A dream come true, says David Barnett, but it won’t be an easy task

At a time when comic book movies rule the box office, it makes sense that one of the most beloved series in recent years gets an adaptation, courtesy of Netflix.

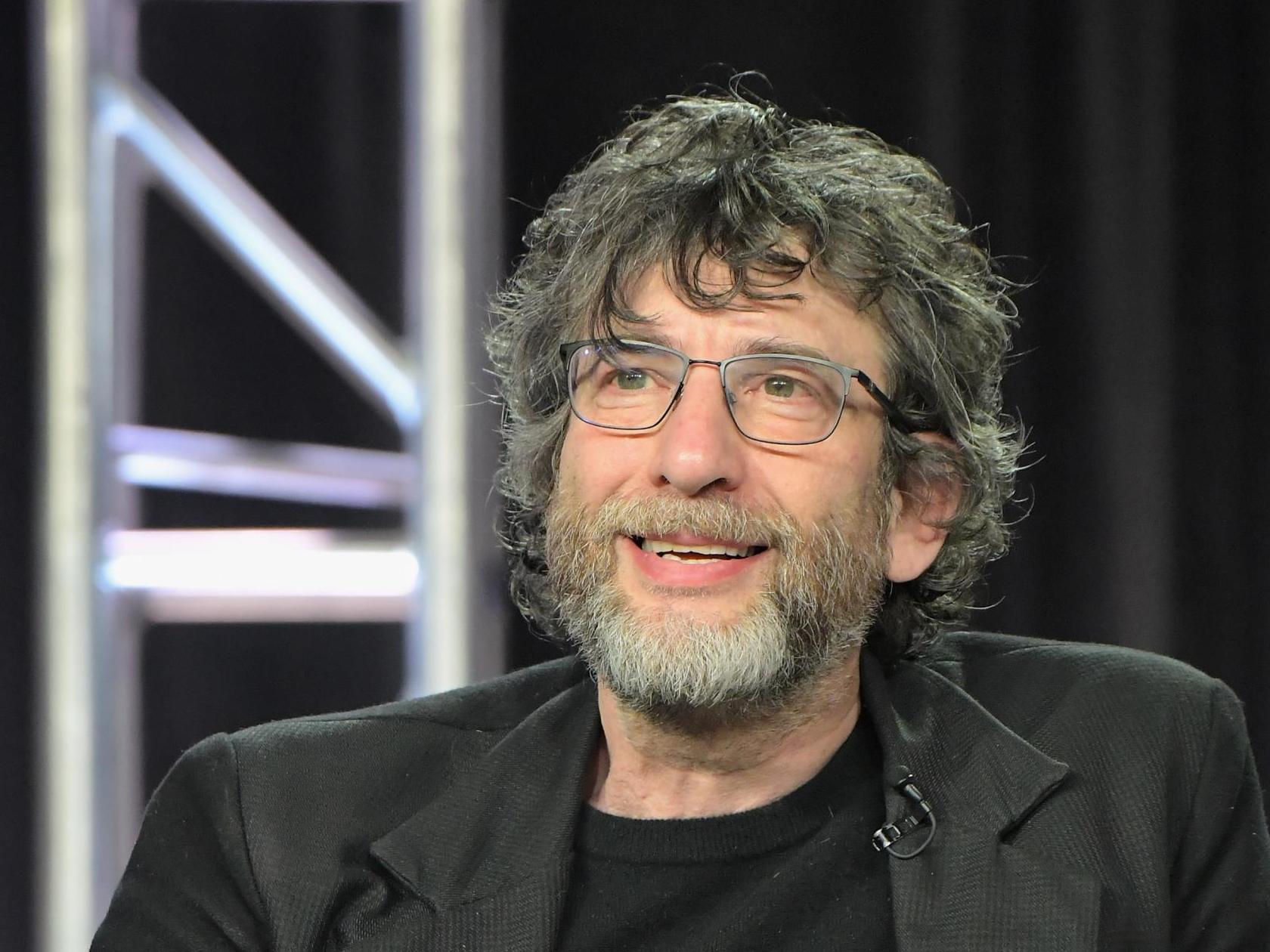

When it’s a comic that was written by Neil Gaiman, the man behind book-to-TV hits American Gods and (co-authored with Terry Pratchett) Good Omens, it seems even more of a no-brainer.

But while the comic in question, Sandman, holds a special place in the hearts of readers of both the hardcore geek variety and those who would never class themselves as comic nerds, its journey to the screen has been a troubled one and for many years the series was dismissed as simply unfilmable.

When DC Comics published the first issue of The Sandman, with a cover date of January 1989, the industry was in the throes of a revolution.

Titles such as Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns heralded a new direction. It was proclaimed “Comics aren’t for kids any more!” as the superhero genre became grittier and darker, drenched in sex and violence that was much more than a sock on the jaw and a KA-POW! Sound effect.

DC Comics, once the home of corny, brightly-coloured heroes such as Plastic Man and Arm-Fall-Off-Boy (no… really. He could take his arm off and hit people with it), was getting cool again. And that was largely thanks to a concerted effort to bring in British writers and artists to overhaul some of their tired old plotlines and dream up brand new characters.

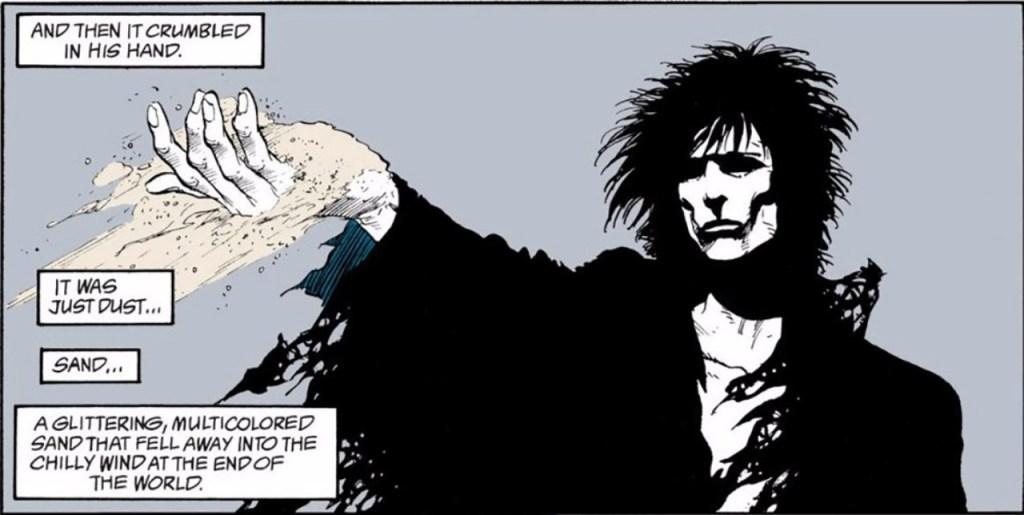

A little before Sandman was published, DC brought out a comic called Hellblazer, featuring a British, street-level occultist called John Constantine who smoked and drank and screwed people over. Written by Jamie Delano, with art by John Ridgway, it set the tone for what was to come. In late 1988, DC started running ads for Sandman in the back of its comics. They showed a twinkle-eyed, pale-faced figure and the slogan, “I will show you terror in a handful of dust”.

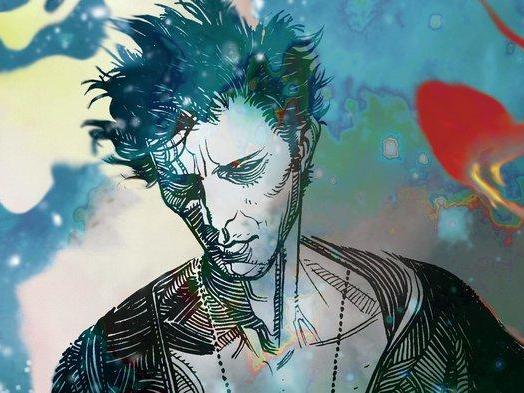

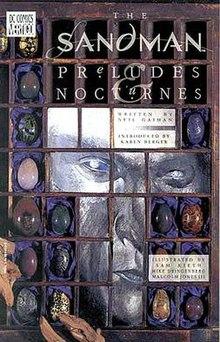

It was written by Neil Gaiman, with art initially by Sam Kieth and Mike Dringenberg and covers by Dave McKean. The advertising blurb was a slight mangling of a quote from TS Eliot’s “The Waste Land”. Gaiman was a name that no one outside of comics would have recognised at that point; he’d been brought over to work for DC by forward-thinking editor Karen Berger after a smattering of comics work, including a graphic novel with the aforementioned McKean called Violent Cases. Sandman was published in the same format as the usual DC superhero comics, and billed as a “horror-edged fantasy”.

Sandman certainly wasn’t about superheroes, though they sometimes featured in slightly grotesque ways. It wasn’t really a horror comic, though it was often horrific. It was fantastical rather than the epic fantasy of the doorstep-sized novels that filled the bookstores. If it wasn’t these things, then what was Sandman all about?

The clever answer is that it’s about everything. In 75 monthly issues, from 1988 to 1996, Sandman covered every conceivable topic, from myth and legend to love and loss to identity politics to horror to birth and death to cats that hunt humans and dogs that talk. In a narrower sense, it’s about the Sandman, also known as Morpheus or Dream, one of a group of immortal siblings known as the Endless who rule over realms that correspond to, really, the components of the human heart. Alongside Dream, the roll call includes Destiny, Despair, Delirium, Destruction, Desire and, of course, Death.

Dream is tall and thin, with skin like snow and hair like night, and eyes that shine like diamonds. He rules over his domain where humans visit, fleetingly, as their bodies rest. He’s actually – whisper it – a bit boring. He doesn’t have much of a sense of humour, isn’t given to snappy rejoinders, and is often brooding over something, some lost love or threat to his realm. So it’s a good job that The Sandman comics are not really very often about him. They’re about the humans who interact with him, and their stories, their lives, which Dream sometimes just witnesses, and sometimes intervenes in.

Though Sandman is a narrative that covers much territory, not always in linear fashion, there is a silver thread running through all 75 issues (later collected into omnibus editions for easier reading) which begins with our introduction to Morpheus, imprisoned for decades by an opportunistic Aleister Crowley-like English occultist. When he’s finally free, the Lord of Dreams returns to his realm to find it crumbling and in disarray, and sets out to retrieve his objects of power, fix things up, and make right all the chaos that has occurred in his absence.

In early issues, he has to track down the denizens of his domain who have escaped while he’s been gone, and travel to hell to free a lover he wronged thousands of years previously. He meets Shakespeare and gods and ordinary people thrust into ordinary situations. The series ends with his death; but like everything that went before, nothing is as it seems in the land of dreams.

The series was an instant hit. It was the comic for people who didn’t read comics, and the comic for those that did. Gaiman must have cast some bewitching hex, because he managed to build a fanbase that was full of cool people and outsiders and comic nerds and punks and pretty much everybody. Everybody loved Sandman. The singer-songwriter Tori Amos loved Sandman. The great American man of letters Norman Mailer called Sandman “a comic strip for intellectuals”. Charles Shaar Murray, the music journalist and author, writing in this very newspaper in 1997, on the release of the final volume of the collected Sandman story, called it “a major achievement. There is nothing quite like it anywhere else.”

A plethora of artists have illustrated the Sandman comics. They include Colleen Doran, Jill Thompson, Bryan Talbot, Mark Buckingham, Malcolm Jones III, Charles Vess, Kelley Jones, Matt Wagner, P Craig Russell, and more. All have brought their own touch to Dream and the Endless, but of course the one constant has always been writer Neil Gaiman.

In a way, Sandman is a timeless tale … And, as you’d expect, many of the stories within the wider narrative deal with how we dream, how dreams affect reality and vice versa, and what happens if we don’t dream… or dream too hard

Gaiman was pretty much an unknown when he started writing Sandman. He wasn’t even that well known a year or so later when he published, along with Terry Pratchett, the novel Good Omens. By the year 2001, when his first proper solo novel, American Gods, was out, he was a little better known, enough to be interviewed by CNN. He demurred at the suggestions that he was now famous, commenting: “I’m not and never will be a John Grisham.”

Still, he had his fanbase by then, and it was quite a wide-ranging one. He is quoted in the same interview as describing his market as “a handful of beautiful goths and a handful of boys in dresses and a handful of sci-fi fans and a handful of nervous young girls with multicoloured hair and the people who look normal and the people who look like somebody’s mum. I exist at the intersection of a dozen Venn diagrams.”

Now, though, it could be argued that Gaiman has certainly achieved Grisham-esque levels of literary fame, certainly since his 2013 novel The Ocean at the End of the Lane took up residence at the top of the bestseller lists. From then on, Gaiman became a hot property.

His works Stardust and Coraline have been adapted into movies, but it wasn’t until the rise of the big-budget, ambitious TV series, heralded by the likes of Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead, that his oeuvre found its natural home. American Gods and Good Omens have both been adapted for TV on Amazon Prime, and Sandman is next, snapped up by Netflix earlier this month.

It’s not quite a case of a goldrush to mine Gaiman’s back catalogue for new hits though. For starters, unlike most of his other work, Sandman isn’t Gaiman’s copyright; he did the work for DC comics, and the characters he wrote and created belong to them. DC certainly hasn’t been resting on its laurels with turning its intellectual property into TV shows… series such as Arrow, Supergirl, The Flash, Titans and Doom Patrol have been big hits. Shows that are more thematically aligned to Sandman, such as Constantine, based on the comic Hellblazer, appeared, while another adaptation at the darker end of the DC universe, Swamp Thing, has just debuted.

People have been trying to get Sandman on to the screen for almost as long as the comic has been produced. From the late 1990s, Warner Bros, which owns DC Comics, had been trying to get a Sandman movie made. Roger Avary, who worked alongside Quentin Tarantino on Pulp Fiction, was slated to direct, but fell out with the company and it never happened. New attempts were made; one screenplay sent to Gaiman is said to have evoked the response from him that it was “not only the worst Sandman script I’ve ever seen, but quite easily the worst script I’ve ever read”.

By 2013, when Sandman had been in and out of development hell more often than the character had been in actual hell (which was quite frequently; the TV series Lucifer, starring Tom Ellis, is essentially a spin-off series of Sandman, featuring the version of Satan that Gaiman created for the comic), something more concrete appeared to be on the cards. Producer David S Goyer announced that he would be leading a film adaptation, working with actor and filmmaker Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Gaiman, with British screenwriter Jack Thorne on script duties.

It underwent several rewrites and by 2016 Gordon-Levitt dropped out of the project, citing differences with the studio over how he thought the direction of the movie should go. The adaptation petered out, with the general feeling that the scope and breadth of Sandman was just too ambitious to be contained in the movie format.

Enter, not Sandman, but Netflix. On 30 June it was announced in Hollywood Reporter that the adaptation was back on, only as an ongoing series on the streaming TV provider, not as a movie. Which is pretty much the best result for a story of this size. David Goyer is back on board, as is Gaiman, whose stock in the TV world has massively risen since the adaptations of Good Omens and American Gods, which he executively produced.

One possible question mark people might have over the adaptation is whether the Sandman story has any relevance in 2019, more than 20 years after the main series ended (there have been many spinoffs, and DC recently launched a Sandman Universe of titles featuring the characters, overseen by Gaiman but created by a new team of comic writers and artists). Good Omens is of a similar vintage to Sandman, but its apocalyptic themes were frighteningly recognisable in this year’s Amazon Prime adaptation, and American Gods was brought up to date nicely with its story of the old gods fading as faith in them wanes, and the new gods of technology, money and sex on the rise.

In a way, Sandman is a timeless tale. It’s character-driven rather than plot-heavy, which suits the Netflix model of delving into characters’ backstories and fleshing out the source material it adapts. And, as you’d expect, many of the stories within the wider narrative deal with how we dream, how dreams affect reality and vice versa, and what happens if we don’t dream… or dream too hard. And dreams are not merely the stories we tell ourselves in our sleep; they can be hopes and ambitions and wishes for ourselves and others. Perhaps there’s something to be said, also, about how willingly we submit to non-real states, especially online, which wasn’t a real consideration when Gaiman first wrote the series.

Overall, Netflix certainly seems a safe pair of hands, and if anyone can do justice to the sprawling story of Dream and the Endless, then this old comics fan thinks it’ll probably be them. Another misgiving aficionados of the comics might have is that over its 75 issues, The Sandman didn’t really plough the sort of neat, linear furrow that TV series like to follow. Sandman is about everything, and that’s sometimes a big ask for a TV show to take on… and which led to the general opinion that it was simply not a thing you could adapt.

It’s also a truth that great comics – or novels, for that matter – don’t necessarily make great TV shows or movies. To revisit an earlier point, a comic book isn’t just illustrated fiction. It’s a collaborative medium, it’s its own way of telling stories. It’s writing and art that come together to make a way of communicating a narrative that is different from anything else. Sometimes, that story is best suited to the form in which it was first birthed. And even if it all goes wrong, at least we still have the comics.

But people are undeniably excited about a Sandman TV show. The beautiful goths, boys in dresses, sci-fi fans, nervous young girls with multicoloured hair and the people who look normal who were Gaiman’s turn of the millennium fanbase. As will, finally, thanks to Gaiman rapidly becoming a household name, “the people who look like somebody’s mom”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments