Neil Gaiman interview: ‘I didn’t do it for the critics or the audience... I made Good Omens for Terry Pratchett’

Thirty years after publication, the story of an angel and a demon on a mission to stop armageddon is more relevant now than ever. But, the author tells David Barnett, it almost never made it to the screen at all

In the first episode of Good Omens, Aziraphale, an angel, played by Michael Sheen, and Crowley, a demon (a cat-eyed David Tennant), are sitting by the duck pond in St James’s Park discussing the imminent end of, well, everything. The Antichrist has been born into the world and – this might sound familiar if you’re au fait with the whole Antichrist apocalypse movie genre – has been cunningly placed by Satan’s soldiers on the earthly plane with the family of an American diplomat.

The reference to The Omen from 1976 is not lost on Aziraphale, nor is the fact that he’s one of the lead characters in what’s sure to be one of the biggest TV hits of the year. “An American diplomat,” he sighs. “Really? As if armageddon were a cinematographic show you wished to sell in as many countries as possible.”

Were this Fleabag, Michael Sheen would at this point have raised an eyebrow at the camera. The six episodes of the show are unleashed in their entirety on Amazon Prime tomorrow, with a BBC broadcast in weekly parts to come later in the year. By which time, yes, it probably will have been seen in as many countries as possible.

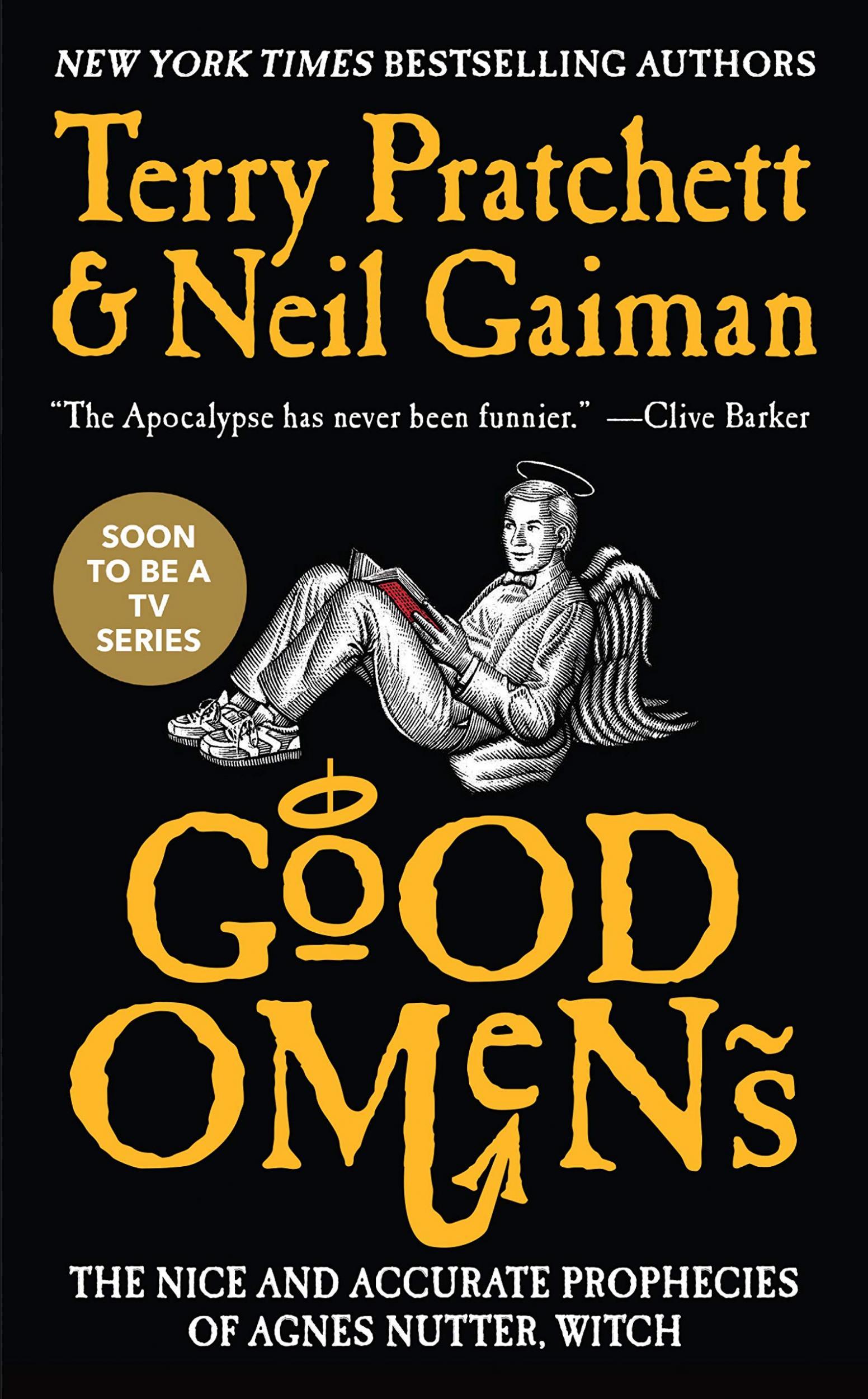

Good Omens the novel was originally published in 1990, a collaboration between Sir Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman. If you’re familiar with Pratchett, it might be through his Discworld novels and their Sky TV adaptations. Similarly, you might know Neil Gaiman from The Sandman graphic novels, his bestsellers The Ocean at the End of the Lane and Norse Mythology, or the Amazon Prime adaptation of his 2001 novel American Gods.

Good Omens is none of these, yet has flavours of all of them. It’s apocalyptic, of course, dealing with the fact that the end is exceedingly nigh, much like American Gods. And it’s funny, too, laugh-out-loud funny in parts, as are Pratchett’s Discworld books. But it’s very much its own thing, the fruit of a combination of rare talents, and something never, sadly, to be repeated.

On Tuesday evening a premiere was held for the Good Omens TV series in London’s Leicester Square. On the front row of the cinema there was a reserved seat that nobody ever sat in. It was instead occupied by a hat, scarf and box of popcorn.

“When we used to talk about Good Omens and whether it would ever be a film or TV show,” says Gaiman, “Terry always used to say he would not ever believe anyone would adapt Good Omens until he was sitting there watching it and eating popcorn, and would probably not believe it even then.”

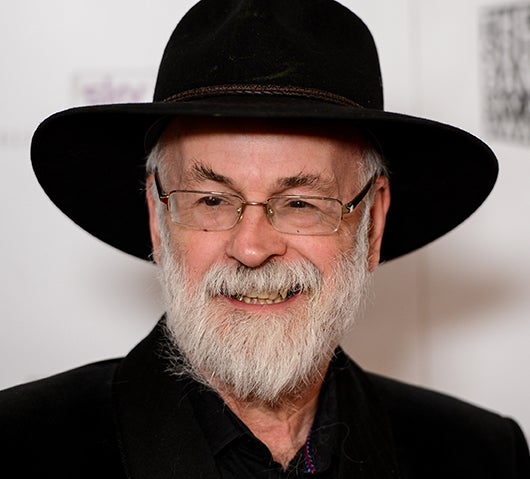

Pratchett died in 2015, aged just 66, eight years after going public with the fact that he had been diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s. He was already a national treasure by then, thanks to his prolific output and, in his latter years, becoming a patron for the Alzheimer’s Society and making a BBC documentary about living with the condition.

After a career as a journalist and a press officer for the Central Electricity Generating Board, he became a full-time writer in 1987, after the publication of his fourth Discworld novel, Mort, and settled into a role as a true literary character, rarely seen without his trademark black fedora hat. It was that hat that took pride of place on the front row of the Odeon on Tuesday night.

“Having Terry Pratchett’s hat front-and-centre with a big bag of popcorn meant the absolute world to me,” says Gaiman.

Good Omens was born when Gaiman wrote the opening chapter and sent it to his friend Pratchett to see what he thought. It had a working title of “William the Antichrist”, riffing off the very British rough-and-tumble William books by Richmal Crompton, and posited the simple question: what would happen if the son of Satan was an ordinary boy from Suburbia?

Gaiman recalls: “I didn’t hear anything for about eight months, by which time I was heavily involved in writing Sandman [the comic series for DC that made his name as a writer]. Terry called me and said, ‘That thing you sent me, are you doing anything with it? If you want, you can sell me the idea, or we can do it together.’”

They plotted the novel together over the phone, and would write chunks of the story individually, exchanging their work on floppy disks sent through the post. When it was published, the book garnered a clutch of genre nomination awards and became a firm favourite among fans of both authors.

There had been mutterings about some kind of screen adaptation of Good Omens since around 2011, but following Pratchett’s death Gaiman declared publicly that he would never embark on such a project without his friend and collaborator. Then Gaiman received a letter, written by Pratchett before he died, who had presciently anticipated that TV was becoming a much mightier force in terms of sprawling adaptations, and urged Gaiman to forge ahead with a Good Omens show. The missive from beyond the grave was entirely in keeping with Pratchett’s sense of humour, and so on-message with the whole tone of Good Omens that it might as well have been a discarded plot point.

Pratchett might have gone, but we still have his representative on earth in the shape of Rob Wilkins. Wilkins had been a constant figure by Pratchett’s side for years. He was described as Pratchett’s assistant, but that doesn’t really cover how deeply Wilkins was embedded in Pratchett’s career and life. So much so, that along with Gaiman, he is an executive producer on the Good Omens series.

The obvious question for Wilkins is what would Pratchett think of the show? It is, as you might expect, one he’s been asked a lot recently. “In Terry’s lifetime, I had no idea what he thought about anything,” laughs Wilkins. “Some days he would want milk in his tea, some days not. Terry Pratchett was a very difficult man to predict.

“But the question of what Terry would have thought of Good Omens is actually a very simple one to answer. Having Neil Gaiman as the showrunner, having him on set since day one, knowing everything that Neil has put into this show, the birthdays and anniversaries he’s missed, the novels he hasn’t written… Terry would just have been delighted that Neil’s been the one to see this through.

“He would have loved everything about Good Omens, from the production to the design to David Arnold’s music, and he would have absolutely loved Neil’s screenplay.”

It’s been an exhausting few years for Gaiman, who has poured everything into the Good Omens production, shuttling back and forth between London and his home in the US, where he lives with musician Amanda Palmer and their young son Ash. He says: “It feels like I’ve been climbing a mountain, and I reached the peak of it in January or February, when the production was finished. When the show is launched on Amazon Prime on Friday I’ll finally feel like I’m starting to head back down the mountain and go home.”

The idea that 30 years on humanity has done absolutely nothing about these things just strikes me as obscene. This is essentially the same Good Omens story as it was then, it just happens to be a lot more appropriate now than we could ever have imagined

After months and months of filming and locking himself away in dark editing suites, Gaiman finally got to see the six episodes of Good Omens in their entirety and in the correct order for the first time last week. “It was incredible,” he says. “To see it all, made by the best crew you could ever get, with such an amazing cast.”

The cast really is a stellar one. Tennant and Sheen head it up, of course, but there’s plenty of talent on the screen around them, from Jon Hamm as the officious angel Gabriel, to Anna Maxwell Martin’s Beelzebub, Josie Lawrence as remarkably accurate soothsayer and Lancastrian witch Agnes Nutter, Jack Whitehall as the descendent of a witchfinder general. Veteran actor Brian Cox lends his stentorian tones to the voice of Death, Frances McDormand offers a very soothing God voiceover, while Benedict Cumberbatch plays her Satanic counterpart.

And while Good Omens hits screens with incredible production values, as we’ve come to expect from the most high-end contemporary TV extravaganzas, it is a very British show indeed – especially where the humour is concerned.

The central idea follows Sheen’s Aziraphale, an angel who has become quite accustomed to living a comfortable life on earth, running a bookshop and enjoying classical music, sushi and the finer things in life. Tennant’s Crowley is a rockstar of a demon, flying by the seat of his pants and doing just enough – aided by overblown reports to his bosses in Hell – to ensure he can live a decent and undisturbed life as the Other Place’s emissary in the mortal world. Over the millennia, the two have developed a close friendship, despite their obvious differences, and the prospect of armageddon bringing their lives crashing down does not sit well with them at all.

The main plot device is a classic trope of British comedy. Entrusted with getting the newborn Antichrist into the care of the unwitting American diplomat and his wife, Crowley becomes embroiled in a farcical (in the finest way) episode with an order of Satanic nuns involving a three-way baby switch which, inevitably, results in the actual Antichrist mistakenly going to live with an unassuming couple played by Daniel Mays and Sian Brookes.

There’s something almost gloriously Carry On about the scenes in the convent (without the smut), and Gaiman throws out a whole slew of references and inspirations for the comedic aspects of the show, from the films of Powell and Pressburger to Monty Python’s Life of Brian to Douglas Adams.

In fact, the opening sequence of the first episode, in which McDormand’s God brings viewers rapidly up to speed, is incredibly redolent of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which Adams wrote as a radio show, then a series of novels, then a 1981 TV show, and that’s no accident.

“That’s definitely a homage to Hitchhiker’s,” says Gaiman. “It’s perhaps what it would look like if they made a TV series of it now.”

The curious thing about Good Omens, perhaps, is that for an adaptation of a novel that was published almost 30 years ago, it seems actually as relevant today as it did in 1990… in fact, more so. Pratchett and Gaiman started writing the novel in 1988, when the world was just about to start emerging, blinking, from the depths of the Cold War. By the time it was published in 1990, there was almost whiff of optimism in the air.

“There was a line we put into the novel, between the first and second drafts, that reflected that,” says Gaiman. “We said something like wasn’t it a shame armageddon had to happen, because there was Glasnost and the Berlin Wall coming down, and everything was starting to feel a bit nice.

“When it came to writing the screenplay, I realised I couldn’t put that line in the TV show because the idea of everything starting to feel nice would just make it feel so dated. None of the problems we talked about in the book, from climate change to war, appear to have been sorted out. The idea that 30 years on humanity has done absolutely nothing about these things just strikes me as obscene.

“This is essentially the same Good Omens story as it was then, it just happens to be a lot more appropriate now than we could ever have imagined.”

Gaiman got the scripts drafted in summer 2016, in the wake of the Brexit referendum, the result of which surprised him. And the US presidential election campaign was getting underway. Gaiman says: “So I thought, OK, this has happened in Britain. But the American’s aren’t idiots, they’re not going to elect Donald Trump…” He pauses and adds: “I identify with people who like the world, people who want to continue living there calmly, who want to raise their children to think it’s a good thing that the world has a future.”

Where, in other words, armageddon is confined to works of entertainment such as Good Omens. It’s been a long old haul getting Good Omens to the TV screen, and Gaiman confesses that had he known just how much work it would be, how much time and energy it would eat up, he might have had second thoughts about taking the project on.

But Wilkins is adamant that only Gaiman could have brought his and Pratchett’s vision to life like this. He says: “Neil was on set every day, in the edit suite every day, in post-production every day. Without Neil, the Good Omens series just could not have happened.”

And, says Gaiman, “once you start walking down that road, there’s no turning back.” But he didn’t make Good Omens for himself. He says: “I didn’t do it for the TV critics, I didn’t do it for the audiences, I didn’t even do it for Rob, I didn’t make it for anyone, except for one person. I made Good Omens for Terry Pratchett.”

Willikins tells us that Pratchett would have loved Good Omens. But imagine if he’d been here to not only see it, but be involved in the production itself. Gaiman smiles, and knows exactly how that would have panned out. “What would have happened if Terry had been alive is that I would have sent him the scripts and he would have said, yes, very good, but I’ve just played with a few things. And he would have made it exactly 17 per cent funnier.”

Good Omens will be available in its entirety on Amazon Prime tomorrow

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments