Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe: 'Boris, I want my wife and daughter home for Christmas,' says husband Richard

The Iranian-British woman has now been imprisoned for 570 days, accused of being a threat to Iranian national security, while her three-year-old daughter remains with her grandparents in Tehran

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

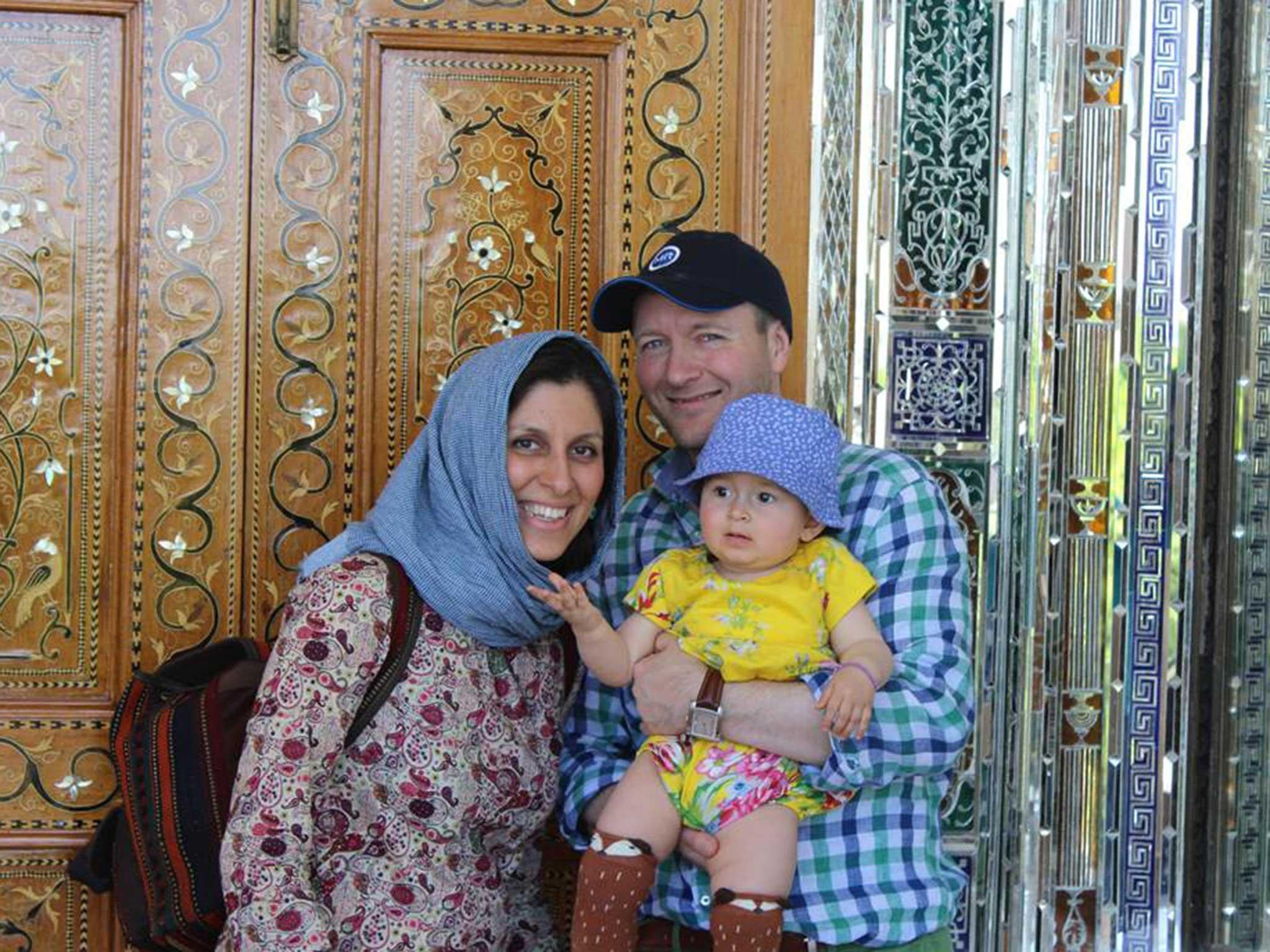

Your support makes all the difference.In April 2016 Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was arrested by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard as she tried to return home to London with her 21-month-old daughter Gabriella after a two-week holiday.

The dual British-Iranian national has been in jail in Iran ever since – despite all who know her saying it is ludicrous to suggest the 38-year-old charity worker had anything to do with spying or seeking to undermine the Iranian regime. Gabriella, now three, remains at the Tehran home of Nazanin’s parents, with her mother in a high-security Iranian jail and her father in London.

Here, on the 570th day of Nazanin’s captivity, her husband Richard Ratcliffe details how she has endured treatment amounting to torture, and demands that Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson act now to get his wife and child home in time for Christmas.

Gatwick Airport, 17 March 2016: that was the last time I saw my wife and daughter in the flesh.

I remember the meal at Giraffe. I remember Gabriella running through the airport giggling, 21 months old, gleeful at what fun it all was, Daddy following after, trying to steer her away from the passengers with heavy suitcases, grinning apologetically.

Then she gave Daddy a goodbye kiss and went with Mummy to the departure gate, spotty blue nursery rucksack on her back, Peppa Pig toy inside.

Between Nazanin and me, there was no great romantic parting – why would there have been? I wished her good luck with our one and three-quarter-year-old on the long-haul flight to Tehran. She just told me: “Make sure you look after the house, and paint that living room wall!”

It was that prosaic.

I went back to our north-west London home to do the list of jobs she had given me – or to put them off. I was more interested in what was going to happen in the England-Ireland rugby match.

Iran, for me, had become a much kinder, much warmer place than the one you see in the news reports about its politics. It was where I had been four happy times with Nazanin. It was where we had gone to celebrate our wedding, where we had gone to show off Gabriella after she was born. It was where I had first gone in 2009, intending to ask Nazanin’s father for her hand in marriage.

He had put it beautifully: “One god, one wife – am I clear?” A very, very good man.

Nazanin and Gabriella were with those good people now, enjoying the Iranian New Year celebration Nowruz – a bit like the British Christmas. They were safe. They would be home in two weeks.

Nazanin has now been in Iranian prisons for 570 days. Gabriella remains at her grandparents’ house in Tehran, no longer a toddler but a three-year-old girl.

The big bowl of fruit I made for them in anticipation of their return – proudly getting the bananas and satsumas that were Gabriella’s favourites – has long ago rotted away.

Nazanin has been subjected to interrogations, to solitary confinement, to – let me be blunt – torture.

We know only that the charges on which she was tried and given a five-year sentence in September 2016 related to “national security matters”. We still don’t know precisely what they were. Because we have never been told.

Nazanin is a charity worker, a project manager for the charitable foundation of the Thomson Reuters media organisation. Yes, there is a link with a media organisation, but no, as I have had to tell interviewer after interviewer, that does not make a charity worker a spy. The Thomson Reuters Foundation doesn’t even operate in Iran.

The simple truth is Nazanin is a British citizen – an innocent British citizen. But in 570 days in Iranian jails, she has never once been allowed to meet with an official from the British embassy.

And though the Foreign and Commonwealth Office has said it is concerned, and then seriously concerned, never has Boris Johnson or anyone else from the FCO said plainly and publicly that what is being done to Nazanin is wrong. Never. Not once.

For her sake, I have promised never to take Gabriella away from Iran without her say-so. She is my wife: she lives for those prison visits from her daughter.

And so, refused a visa to visit Iran, I have watched via Skype as Gabriella lost the English phrases she once had – nearly all of them except “I love you”.

She speaks fluent Farsi now. We have to communicate with gestures: funny faces, pretending to pour each other tea and drink it from little cups.

At first, Gabriella saw the prison visits as “going to Mummy’s bedroom”.

Now she knows the truth: Mummy is in prison.

It took me a while to fully understand it too.

The call came at 5.30am on Sunday 3 April 2016, the day I was supposed to collect Nazanin and Gabriella from the airport.

It was Nazanin’s brother, saying there had been a problem with her passport, that they had missed the plane and would have to catch a later flight.

It was 5.30 in the morning. I had just woken up. I only heard the words “don’t worry”. I missed the worry in his voice. I went back to sleep.

But 24 hours later, Nazanin’s dad went back to the airport. No one there would tell him anything – in Iran, fear of the Revolutionary Guard is all-pervading.

Now I was worried. I remembered the first film we had been to see together: Persepolis, about people disappearing in Iranian prisons, never to be seen again.

So on day three, Tuesday, when Nazanin phoned her family, the relief that she was still alive was overwhelming.

She said she was OK, that she was helping them with their inquiries and they had given her a chelo kebab for lunch – I think that was to reassure her mum that she was eating well.

She said: “They are treating me well.” She didn’t say who “they” were. Someone was sitting beside her listening to the call.

For a long time, I didn’t really process what was going on. I didn’t tell close friends. I didn’t tell people in the office, where work as an auditor entails examining the rather more mundane business of income and expenditure in charity accounts.

If you don’t tell people, you don’t see their reaction, the emotional response, the horror. It doesn’t become real.

But on day 36 I decided the only way to get Nazanin out was to go public, to tell the world what was happening to her. That’s when the “car crash” came: the feelings of guilt and shame – legitimate guilt and shame – that I had let her go through it and done nothing of any real use to help.

Because, make no mistake, Nazanin really did go through it.

They took her to Kerman Central Prison, to solitary confinement in the Revolutionary Guard’s interrogation facility.

That’s where the harshest interrogations took place: a room with one bare lightbulb, some interrogators playing nasty, others playing nice cop, only to reveal days later that they were the nastiest of all.

Some interrogators, she was never allowed to see. They fired questions at her from behind her chair. They told her: “Nazanin, your husband has abandoned you. He is with another woman. He has taken your child away. You will never see Gabriella again.

“Your family are doing nothing for you. You are on your own.”

Anything to make her feel friendless and alone.

And all the time, the crazy questions, the fishing in her email account for connections that just weren’t there.

They seemed to want her help in building her job at the Thomson Reuters Foundation and her work for BBC Media Action, the corporation’s international development charity – eight years ago, as a lowly graduate assistant – into something posing a threat to Iranian national security: “Nazanin, if you just cooperate, this will be over. We’ll let you phone your family.”

My wife, so organised, so tidy, was now in a rough, filthy, provincial Iranian prison. At least there were no feminine touches, no mirror in her cell. She didn’t have to look at her skin growing paler. She didn’t have to see her hair falling out, because of the poor diet, the extreme stress.

In May 2016, on day 39, three days after I went public with a press release and online petition, they allowed a family visit – carefully staged, in a hotel.

By then, Nazanin couldn’t walk unaided without blacking out. She had to be helped into a chair. Gabriella had to be lifted on to her lap.

For 15 minutes, Gabriella said nothing. She sat silent, bewildered, just stroking Nazanin’s cheek, as if to reassure herself that this really was Mummy.

There was a strange dynamic to the cruelty: the guards bought Gabriella a doll.

After more than 40 days in solitary, they let Nazanin onto a wing with other prisoners.

Then on 6 June she was told she was being released. She told her family she would be out in time for Gabriella’s birthday on 11 June.

Then she disappeared. For a week.

It was only on 13 June that her family were told she was now in Evin Prison in Tehran – and they had two hours to get to the jail or that day’s visiting rights would be taken away.

Those are games the Revolutionary Guards play – to us, spectacularly cruel; to them, just part of the job.

Nazanin was in section 2A, under the control of the Revolutionary Guard, in solitary again.

They kept her in solitary until Christmas 2016. All bar 18 days of my wife’s first nine months in captivity were spent in solitary.

At Evin, her solitary confinement cell was about the length and width of a double bed. Although, of course, there was no bed. She had three blankets, one for putting over her, one for a pillow, and one to be the mattress between her and the floor.

Her trial began on 14 August 2016. It lasted all of three hours.

Nazanin was not allowed to talk. Her defence lawyer, whom she had met once before, spoke for five minutes.

Nazanin was allowed to write down a defence – after the court proceedings had finished. Her interrogators read what she had written and were furious. They blindfolded her for that encounter.

Although they removed the blindfold just before letting Nazanin’s lawyer back in the room.

On 6 September 2016, the day after the British Government appointed a new ambassador to Tehran, the day after Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson spoke of hopes for “more productive cooperation”, Nazanin was sentenced to five years in jail.

She went very low. I was able to talk to her by telephone on 23 October. She told me she was suicidal. There was no film quality to this, it was just bloody real.

In that moment, I had no words of comfort. I was simply overwhelmed by the jarring shock that such a loving mum, a woman so utterly devoted to her daughter, could now think it would be easier for everyone if she just ended it.

Nazanin went on hunger strike in November. Her parents were summoned to an emergency intervention, Gabriella with them.

When they saw Nazanin they were horrified, but still she refused to eat. Her mother pleaded, pleaded and pleaded, and then got so distraught she passed out.

Gabriella saw her mother, her grandmother collapsed and her grandfather calling desperately for help. She became hysterical. In the end, it was a mother’s desire to calm her daughter that persuaded Nazanin to eat something.

When I told the media about this, the British Government’s response was that it “stood ready to bring Gabriella home”.

Of course, the Revolutionary Guard showed Nazanin the reports, only too gleeful at the chance to “prove” that her daughter really was being “taken away from her”.

That’s why I promised Nazanin that I would never return Gabriella to London without her permission, without discussing it with her face to face. I could at least spare her the suffering of losing those precious visits from her daughter.

And the brutal truth was, at that point, Gabriella’s passport was still being held by the Revolutionary Guard.

They only deigned to return it in May 2017 – by which time they had effectively detained my daughter Gabriella, a little girl, and a British citizen – in Iran, for more than a year.

As it stands, because I have been refused a visa to visit Iran, I have no way of getting Gabriella back, apart from asking an embassy official to return her to London, against Nazanin’s wishes – something that would be profoundly destructive, both for my wife and my daughter.

Gabriella has already suffered more than enough disruption in her life, and as for Nazanin, this is about saving our marriage, as well as my wife, however long it takes.

When this first started, I spoke to others whose relatives were also in jail in Iran, and to those who had seen their loved ones released and come out the other side. They were the people who persuaded me to go public about what was happening to Nazanin.

I have met with the brother of American-Iranian businessman Siamak Namazi, who is being held in Evin Prison accused of “collusion with an enemy state” – as is, astonishingly, his father Baquer, in his eighties, with serious heart conditions.

I have met in America with Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian, held on charges of espionage and “propaganda against the establishment”, for 544 days.

When we still hoped Nazanin might be home for Christmas 2016, Jason was the benchmark for how bad it could get, for how long she might have to stay in jail.

But now Nazanin has passed Jason’s 544-day benchmark. As Christmas 2017 approaches, we look nervously at what is happening to Kamal Foroughi, a British-Iranian businessman and grandfather – still in captivity after six years, and counting.

To a man and a woman, the Foreign Office people I have met have been cultured, warm, kind, good people. I have no complaint whatsoever about the people.

It’s the policy. It’s the lack of public criticism of Iran, the lack of public defence of Nazanin, and the extraordinary failure to acknowledge even once that her rights have been violated.

It’s the unwavering conviction that the quietly, quietly, softly, softly approach is the way forward – even after the Foreign Office has been trying it for 570 days.

It’s almost like they are denying the reality of what is happening here. Nazanin has been subjected to torture. Her treatment meets the legal definition of psychological torture under both the UN Convention against Torture and UK law.

Both the convention and the International Criminal Court Act 2001 define torture as the intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering, physical or mental. That fits what has happened to Nazanin.

This is psychological torture. It is not due legal process. It is normalised cruelty.

To put it mildly, it merits some public criticism.

We have known since June 2016 that for Iran, Nazanin is just a bargaining chip in some bigger diplomatic game.

That’s when her interrogators told her: “Encourage your husband to tell the British to make the agreement. Let him know that if they make the agreement, his wife will be released without charge.”

She is a pawn, and it is breathtaking what they are prepared to do to an innocent mother, to the woman I fell in love with.

On our first date, the first thing she did was punch me on the shoulder because I had turned up late and – (according to her) – in the wrong place. But the quick lunchtime coffee turned into a conversation I never wanted to end.

When we talk on the phone now, I can hear her clinging on to the life we built together: trying to remember what herbs are on the herb rack, what coats are on the coat hooks, and asking, “Have you cleaned the coffee machine recently?”

In prison she draws pictures for Gabriella to colour in, of the life she wants us to have – Mummy and Daddy together, with Gabriella, and if we’re lucky, a new baby.

For me, on Father’s Day, she carved a woodwork image of us all together, her hair holding the three of us in her embrace.

This month we thought that dream was finally about to come true.

On 8 October Nazanin entered a courtroom having been told to expect early release. Instead she was confronted by a judge going through a 200-page file of new “evidence” for fresh charges that could keep her in jail for another 16 years: “colluding with the enemy”, “getting money for colluding with the enemy”.

And what exactly is this “colluding with the enemy”?

It seems, from what the Tehran Prosecutor General said, that it consists of matters like working for the BBC, even though that was in her first job after leaving university and she never worked for BBC Farsi, however much the Iranian government might hate that service.

Yes, she made travel arrangements for tutors on an international journalism course that involved teaching reporters to encrypt email passwords to protect sources.

But Nazanin never did any of that teaching, she was just the project assistant. Yes, some of the journalists who took the course ended up working for BBC Farsi. And some of them ended up working for Iranian state media.

In court, as the judge went through the charges, Nazanin started sobbing, pretty uncontrollably.

Because of the shock, her body shut down completely. She couldn’t walk. She had to crawl to the judge’s desk to sign to say she rejected the charges.

But she demanded he look her in the eye, and she told him: “If I have to stay in jail one day longer as a result of your actions, God will judge you.”

I rather admire that inner steel. If Nazanin can say that on the inside, then I have to keep going on the outside.

Which is why I am writing this now. Which is why I am saying, unequivocally, that the time for softly, softly and nothing else is over.

The British Government must now acknowledge – publicly – that what Nazanin has been put through is a mockery of justice, a complete violation of her rights.

I know things are happening behind the scenes – although I have never been told exactly what they are and exactly how hard the Government is working.

But now things need to start happening in public.

It is time for Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson to stand up and say: “This is unacceptable. No British citizen should be subjected to this level of abuse.”

Whatever issues are going on between the British and Iranian governments, Nazanin should not have to pay the huge price of being a bargaining chip in those dealings.

It is time for Boris Johnson to say loud and clear that there are no grounds for Nazanin’s detention and she must be released immediately.

I want Nazanin and Gabriella home for Christmas.

To sign the petition calling for Nazanin to be released, visit change.org/p/free-nazanin-ratcliffe

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments