How a London socialite founded the national lottery

Hilda Leyel wanted to raise money for disabled servicemen. Despite initial public disapproval and the threat of criminal charges and imprisonment, her idea stuck. Martin Purdy explains

In December 1921, the public gallery of Marylebone Magistrates’ Court in London was filled with “fashionably dressed ladies’’ keen to hear the latest charges to be levied against a popular socialite called Hilda Leyel. In taking on such a well-connected member of British society, the prosecutors were playing with high stakes – and it was a roll of the dice that would ultimately result in the rules of charitable fundraising being changed for ever across the United Kingdom.

The breaches of the Betting Act that Leyel found herself charged with were all linked to a national lottery – one that by 1920 had already raised more than £250,000 to specifically help some of the 1.7 million disabled servicemen who had returned to home shores from the killing fields of the First World War.

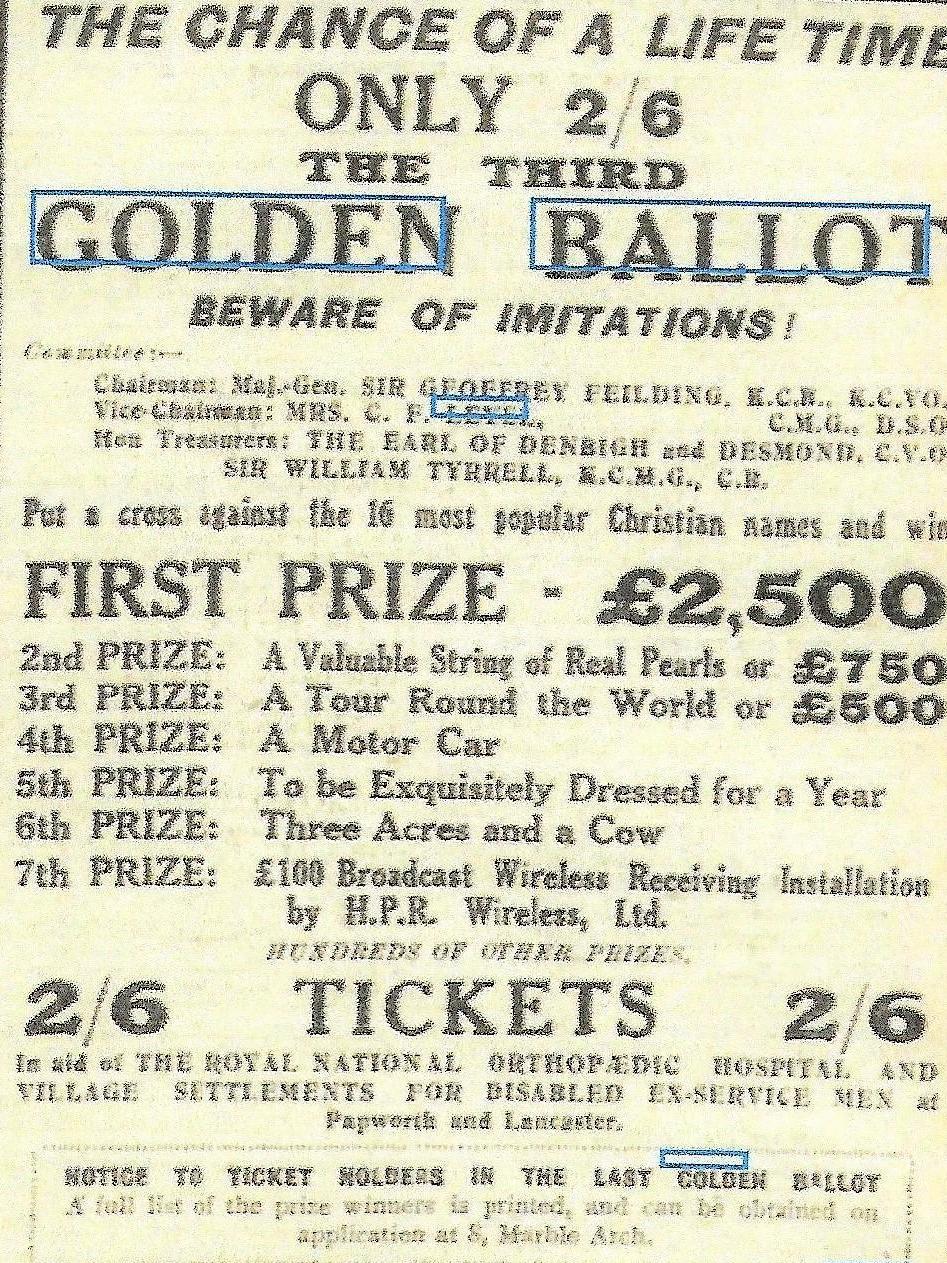

Billed as “golden ballots”, the lotteries were the first of their kind and the forerunners of the same National Lottery that continues to persuade so many of us to part with a smattering of our cash each week. Unlike the modern lottery, all of the profits from Hilda Leyel’s ballots went to hospitals that specialised in the rehabilitation of the wounded of war, including prosthetic limbs, work retraining schemes and bespoke housing projects. Very like the modern lottery, the winners could win life-changing prizes, from £25,000 in cash to strings of pearls – or a cow and an acre of land on which to graze it!

At one of Leyel’s inaugural court hearings in April 1920, the newspaper reports of the day took great delight in pointing out that Lady Asquith, the wife of the prime minister that had taken Britain to war, had been among those present to support the accused. Furthermore, Lady Asquith was said to have shocked those present by laughing out loud when the prosecutor said that among the prizes had been the chance to dine at the Savoy Hotel in London for a week – “allowing the common chimney sweep the chance to experience the life of a Lord’’.

While the society ladies of London may well have been amused by such a concept, the crown was not. Nevertheless, it did accept that the golden ballots were not the work of criminal masterminds and that none involved had personally gained from the enterprise.

This was important as there were certainly some big reputations at stake. Among Leyel’s main supporters were Major-General Sir Geoffrey Feilding, who had served with distinction in the Boer War and successfully commanded an elite Coldstream Guards’ Division in the recent world war, as well as the Earl of Denbigh and Sir William Tyrrell, an assistant under-secretary of state at the Foreign Office.

Ever-mindful of who they were dealing with, the prosecution remained at pains throughout to stress that it did not seek to question the honourable aims of those involved but simply wished to stop a precedent being set that would open the door to more ‘’unscrupulous’’ individuals – people who might use such lotteries to ‘‘feather their own nests’’.

In presenting Leyel with eight specimen charges, carrying a fine of £25 or three-months imprisonment each, they undoubtedly hoped that the socialite would opt to pay up and consign the enterprise to anecdote. They had, however, underestimated her fighting spirit.

Hilda Waughton had been born in London in 1880, the daughter of a schoolmaster from the Uppingham School in Rutland. As a child she had been a keen collector of herbs and flowers and nurtured an ambition to study medicine. However, a secondary passion for acting ultimately changed that – for it was while acting with the Benson Troupe that she met a young Swedish nobleman called Carl Leyel, and before the century was out the teenager and her beau had married.

The Leyels went on to have two sons, both of whom were thankfully still too young to serve when war broke out in the summer of 1914. However, Hilda’s role as an actress would bring her in to contact with many of the wounded of the conflict that was slowly tearing the world apart.

In the pre-war years Hilda had been an honorary treasurer of the Actresses Franchise League (AFL) established to promote female enfranchisement and suffrage via acting, education and leafleting. During the war the AFL, which neither openly supported nor condemned militancy, put its work on hold and formed Women’s Theatre Camps Entertainments. The group performed at army camps and hospitals and it is presumed that it was as a result of this work that Hilda became introduced, and then fully committed, to the care of wounded servicemen. After the war had ended she came up with the concept of the golden ballots to ensure that such men could continue to receive the aftercare and support they so desperately needed.

The sad reality is that successive post-war governments proved themselves far from willing to take adequate responsibility for the disabled of the recent war. While pensions had improved during the conflict, and a more centralised form of care had been established by the creation of a Ministry of Pensions, few historians would argue that the state did anything other than attempt to minimise its financial support. In many ways it was able to get away with this courtesy of the sympathy of the public for the large numbers of disabled men who were providing a highly evocative and visceral presence on the streets of so many communities. In fact, by the time of the Armistice on 11 November 1918, there were already 6,000 charities registered to support injured ex-servicemen.

Nevertheless, as Britain rapidly found itself slipping into a post-war depression, and money became desperately tight for many households, it proved an ever-greater challenge for the charity sector to find ways to get the public to put its hand in its pocket. The old adage that charity begins at home had never been more prescient for families living on the breadline as unemployment levels hit record highs.

In addition to the difficult economic situation, the sheer number of charities operating in Britain – which had doubled to around 36,000 as a direct result of the war – meant that fundraisers were being forced to become far more professional and innovative in order to stand out from the crowd and attract donations. Many of the charitable practices that we now accept as commonplace, from the concept of professional marketing campaigns to the introduction of bespoke charity shops, can be traced back to this period.

The golden ballots were, however, a genuine masterstroke. The public could take part in these ballots knowing that their money was going to support a noble cause, while also offering them the chance to become personally enriched. It’s an approach that modern descendants of the ballots, including our own National Lottery, have continued to attempt to emulate; with the majority of the public’s weekly stake going to support good causes, as well as arts and heritage projects, while a handful of lucky members of the public can win life-changing amounts.

Such was the fame of Hilda Leyel’s ballots, footage of the chic looking socialite can still be found in the British Pathe film archive showing her arriving on the doorstep of unsuspecting members of the public to announce their windfalls. These films were aired in cinemas across Britain, describing Hilda as a “fairy godmother”, and highlighting the potential backlash the crown faced in prosecuting her.

Indeed, the popularity of Hilda Leyel with the public may well have been key to her decision to plead ‘’not guilty’’ to the charges levied against her and instead opt for trial by jury. It was a gamble that ultimately paid off, and her subsequent victory in the High Court in 1922 ensured that ballots held solely to raise funds for charitable causes were, from this point forward, legal. The “golden lady” had changed the face of charitable fundraising in Britain for ever, making her legacy among the most socially important of the First World War.

Despite this, the coverage in the newspapers of the flagship trial and victory was mooted. It appears that the British media, perhaps reflecting the growing public mood at the time, was keen to draw a line under ‘’the war’’ and focus on the brave new world instead.

Likewise, when the heroine of the golden ballots died in April 1957 there was even less fanfare. In fact, she had by that time become much better known as the founder of the Society of Herbalists, the proprietor of a chain of related stores called the Culpeper Shops, and as the author of numerous popular tomes on herbalism, including the highly influential The Perfect Picnic and The Gentle Art of Cookery. Never one to shy away from a battle, she would go on to find herself at the forefront of the fight to ban synthetic fertilisers.

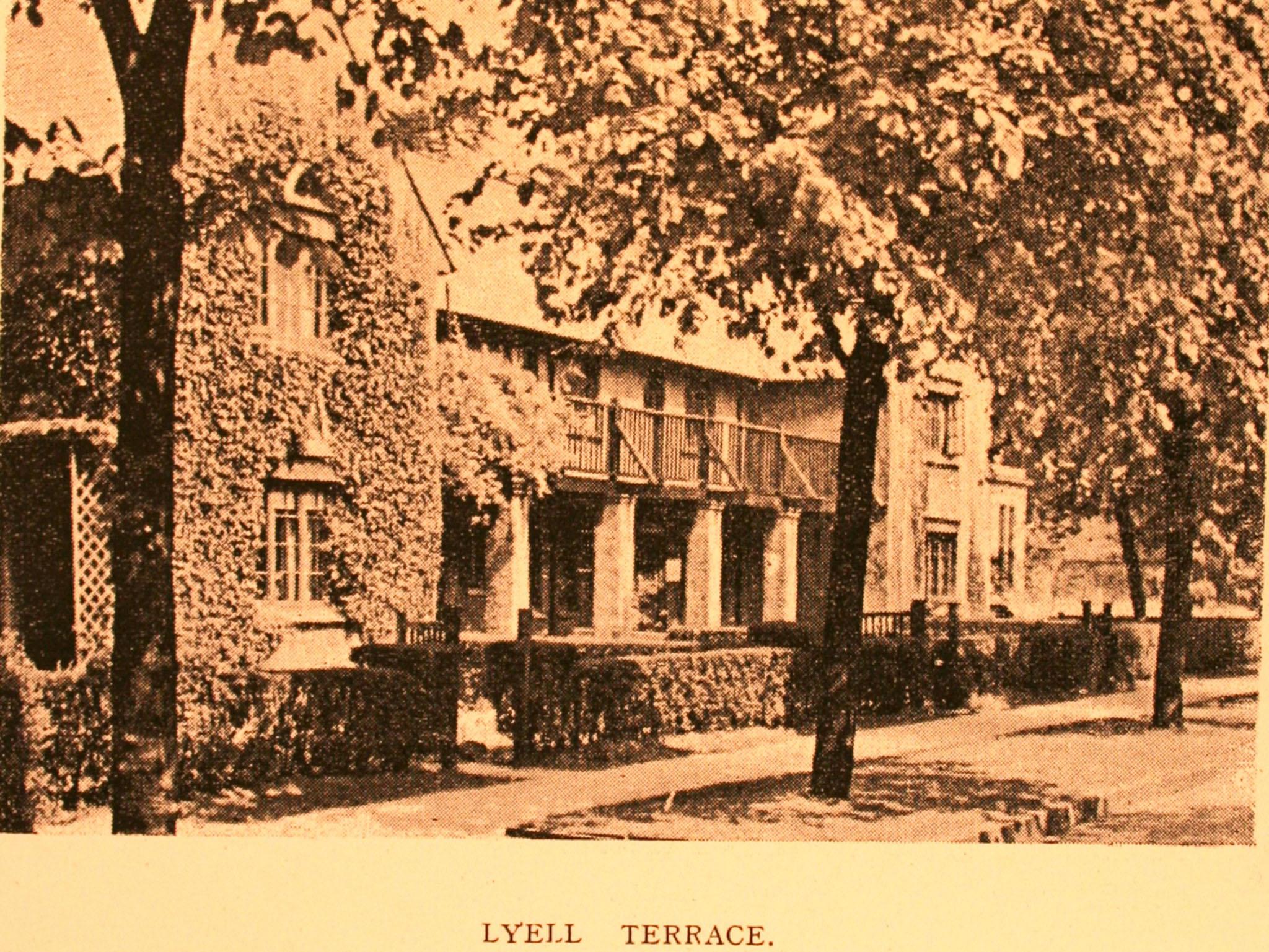

To find any formal recognition of the First World War fundraising schemes of Hilda Leyel you have to visit Lancaster, the former county town of Lancashire and the home of a rather unique settlement for disabled ex-servicemen called the Westfield War Memorial Village. This community marks its centenary in July of this year, and among the 113 homes nestled behind its grand entrance gates are a collection of four conjoined properties bearing the name of “Leyel Terrace”.

The naming of the properties was how the trustees of the Westfield charity thanked Hilda for hosting a second golden ballot on their behalf in the early 1920s. Without the huge amount of money raised – which at £20,000 was in the region of a million pounds at the time – the settlement could not have grown. The money would pay for dozens of new houses, essential utilities such as sewers and pavements and a nest egg to accrue interest that would help support the community in the fallow years to follow.

Such was the scale of the financial input, the lead philanthropist behind the Westfield project, Herbert Lushington Storey, would state in a formal public address in 1926: “If I may be so bold as to say so ... I am afraid if it hadn’t been for the assistance of my friend Mrs Leyel we should not have got very far with the scheme.”

Mandy Stretch, the present secretary of the charity that continues to run the community, is in no doubt about the vital contribution of Hilda Leyel. She says: “As a result of the huge amount of money Hilda raised, hundreds of ex-service personnel and their families around Britain were to benefit at the end of the First World War. It shouldn’t be forgotten that many continue to benefit today. We have residents living here who have fought in nearly every conflict since the First World War – from the D-Day landings in the 1940s through to recent wars in Afghanistan – who are living in properties that were paid for by Hilda Leyel’s second Golden Ballot.”

The Westfield charity will this month unveil a new memorial in recognition of the vital role that philanthropy and charity have played throughout history in the care of Britain’s disabled of war. Needless to say, at the unveiling of the memorial, special mention will be given to Hilda Leyel, the mother of two, actress, suffragist and fundraiser who risked her reputation and liberty to leave a vital and lasting mark on the whole process.

Dr Martin Purdy is the historian in residence at the Westfield War Memorial Village Lancaster and the co-author of such popular First World War books as ‘Doing Our Bit’ and ‘The Gallipoli Oak’. Though old enough to know better, he fronts the internationally acclaimed folk trio Harp and a Monkey.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments