Apollo veterans are helping Nasa with its new moon mission: ‘We are taking it to the next level’

While engineers build on the foundations of the 1969 trip to tackle the next lunar adventure – Trump must overcome scepticism from congress and decide what the new mission means, writes Chris Stevenson

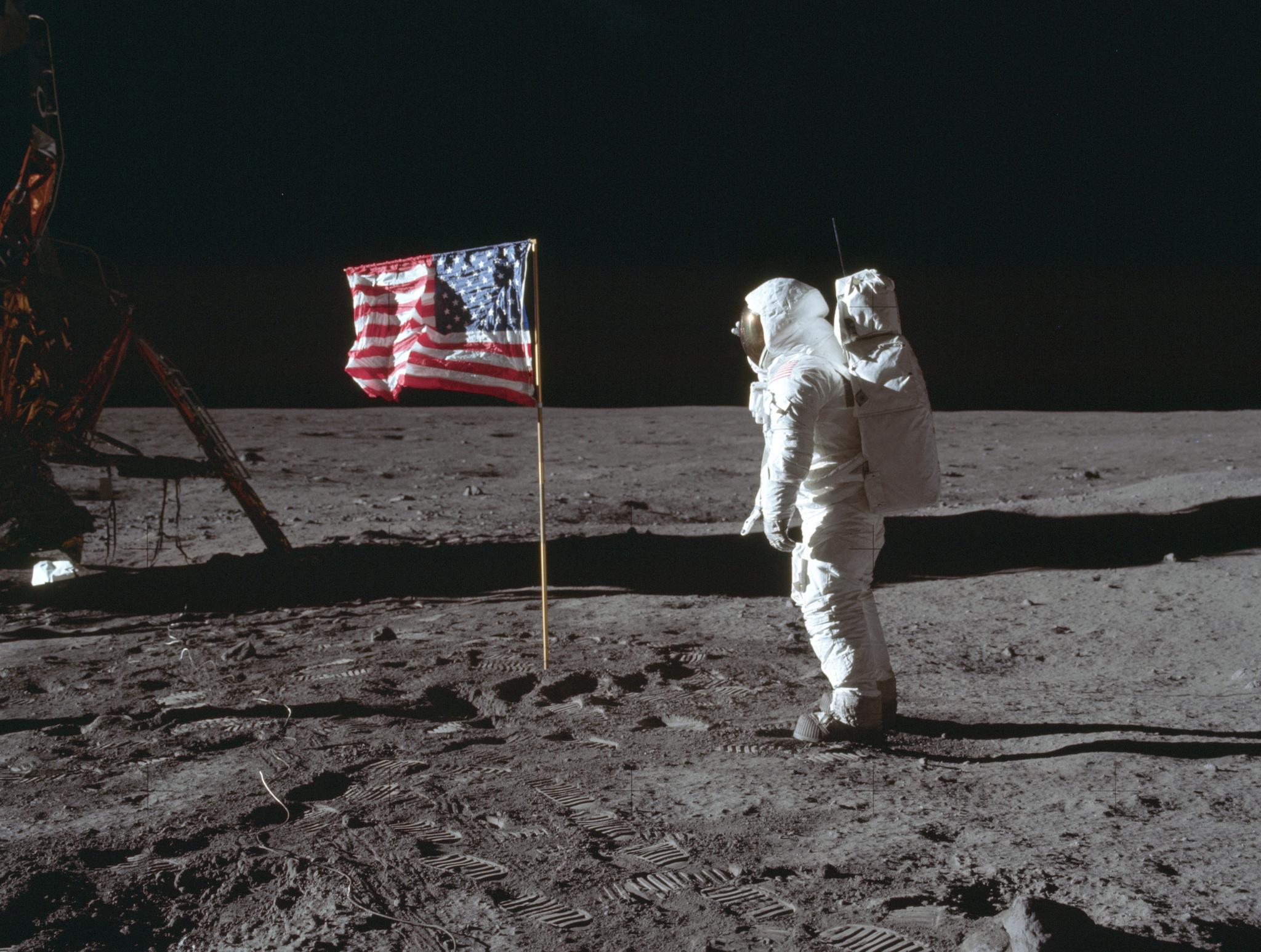

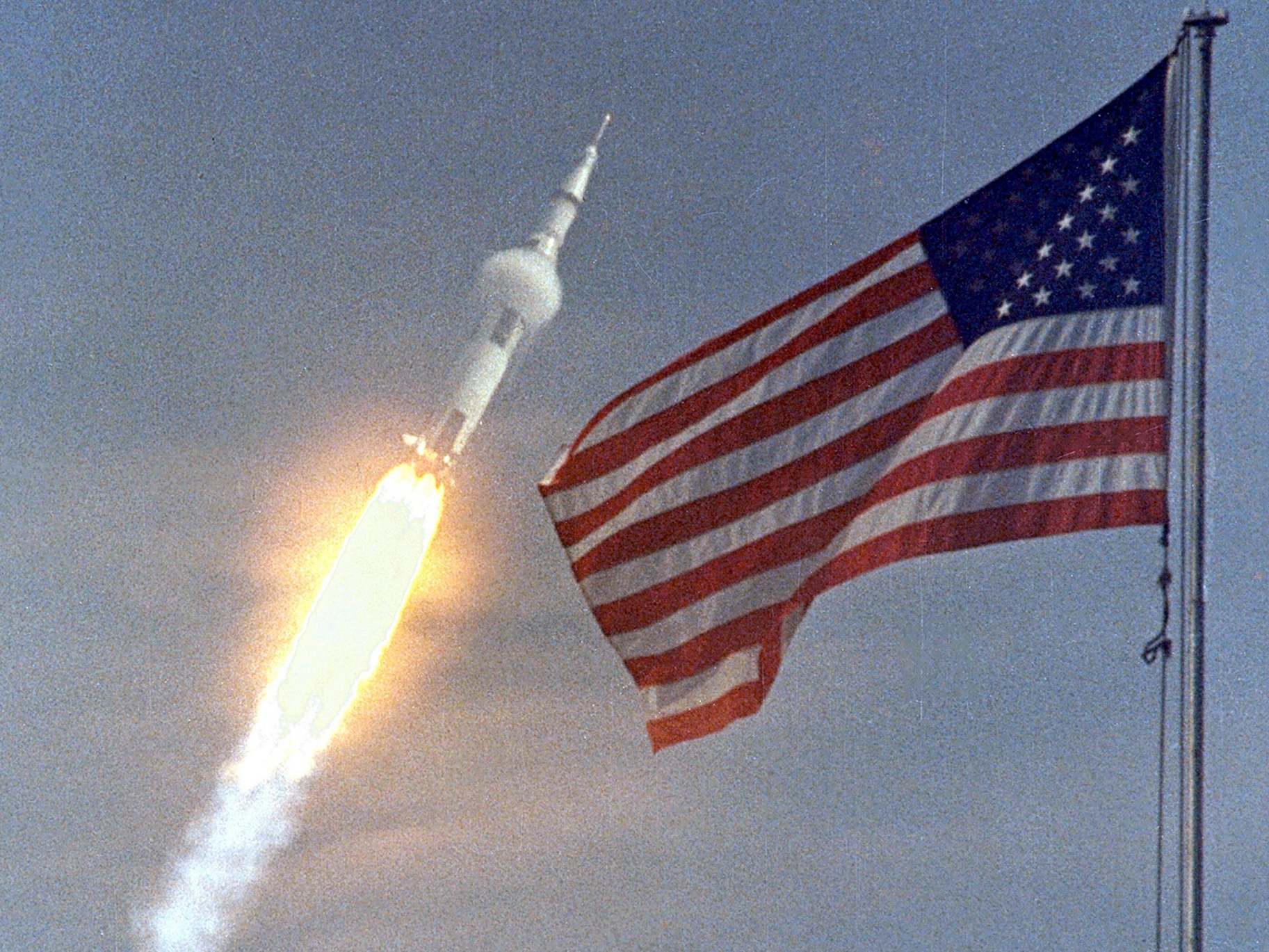

Almost 50 years to the day since Neil Armstrong took his “giant leap for mankind” by stepping on to the moon – Regina Spellman is still in awe of their achievements but her eyes are fixed on what comes next. The Nasa project manager is one of those in charge of refitting Launch Pad 39B, where Apollo 11, containing Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, blasted into space in 1969. Now, the space agency is looking to put the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface in 2024.

“Being able to write that next chapter, knowing what has come before through Apollo and the shuttle programme, and knowing we are writing that next story is amazing. It is humbling to think about what they were able to do... especially considering they didn’t have the computing power we do,” she says. “That we are even in the same conversation... is incredible.”

Spellman should know what the Apollo missions took, she works with veterans of that programme and while Nasa has had to build on that expertise over the past five decades the principles of that era-defining trip underpin everything she does. The current mission, called Artemis, the sister of Apollo, is daunting in itself. Having been set the task of returning to the moon in 2028, Donald Trump’s administration has accelerated that timeline. Vice-president Mike Pence said back in March that the later deadline was “just not good enough” and that “urgency must be our watch word”.

While that may have something to do with that date being the end of a notional second term for Trump, the non-partisan Nasa is taking it in its stride. “It gets me really excited. I’m excited that we now have this really clear goal of boots on the moon by 2024... It is very helpful to have a crisp vision and goal so that we are all working towards the same challenge and the same objective.”

Spellman is glad to not have to start with the “blank sheet of paper” that the Apollo missions did, and that another project manager Ken Poimboeuf has been there and done it. A veteran of the 1960s effort, Poimboeuf said earlier this month: “This place is history in the making and it’s not over yet.”

For Spellman that history is important. “[Ken] has a lot of knowledge but also a lot of the memories of the experiences,” she says. “Sometimes it feels like ‘are we ever going to get there?’ but he has faced those challenges. People who don’t want to let go of the past and people who are excited by the future and he has walked that line between them.”

“It is not going to happen overnight... but it is comforting to know we are going through some of the same growing pains,” she adds.

But the future is what drives the thousands of staff and contractors working on the Artemis mission. “This anniversary [of the moon landing] is definitely a time to stop and think about it – but it matters every day that we are leveraging what they learned through Apollo and the shuttle missions and are taking it to the next level.”

Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy space centre in Florida has seen its fair share of history beyond Apollo, having also been used in the space shuttle programme from 1981 to 2011 – but its latest guise is unprecedented. It will now accommodate Nasa’s heavy-duty Space Launch System (SLS), which will power the crew-carrying Orion capsule into the heavens. As an example of the sheer magnitude of the changes, more than 1.3 million feet of copper wiring used in the Apollo era has had to be switched to fibre optics. “It is a pivotal time for us – we are now testing the mobile launchpad and the launcher together so we are building up the system... we are getting really close to that first mission.” An unmanned test flight of Orion is due next year, with a crewed test to follow in 2022.

Beyond Florida and the Nasa centres across the US, the elements around the mission are fraught. Some members of congress, who have to sign off the budget for Artemis, are wary of the costs and the few details provided so far. “We have a White House directive to land humans on the Moon in five years, but no plan, and no budget details on how to do so,” Kendra Horn, chair of the House subcommittee on space and aeronautics, said back in May just before a 2020 budget was announced. That budget called for an extra $1.6bn to fund Artemis for that fiscal year, on top of the $21bn the president already requested for Nasa.

Costs for the following years are yet to be established but will rise, with estimates that Artemis could cost $20bn to $30bn or more in total. “You are sort of asking congress to put a down payment on a car, but you don’t know what you are buying and you don’t know how much it will cost,” says Dr Mary Lynne Dittmar, who has decades of experience in the space field and is part of the Users’ Advisory Group of the National Space Council – the body reestablished by Trump under the direction of Pence to help guide policy.

Nasa administrator Jim Bridenstine told a Senate panel on Wednesday that a budget impasse and subsequent spending freeze later this year would be "devastating" for the chances of the Artemis mission.

However, with the mission looking to set down roots for “national capability for decades” rather than just two or three trips to the moon, Dittmar believes it is a “different ball game” to the “war footing” of the 1960s space race. Later space missions in the 1970s and 1980s were “trying to apply a model that was specific to that one point in time... now it is a much different landscape”. More infrastructure and more countries are involved – which means the conversations over how missions will take place and what is needed will take longer.

Dittmar does not doubt the political will to put humans back on the moon, but the pressure of the deadline means that things have to happen relatively quickly. Recent staff changes at the top of Nasa, initiated by those within the agency, may indicate that the urgency created by the White House is having an effect.

In his speech in March, Pence raised the prospect of the use of commercial rockets to keep the mission on schedule. “If commercial rockets are the only way to get American astronauts to the moon in the next five years, then commercial rockets it will be,” he said. There are certainly advocates who believe this is the right strategy and it could reduce costs.

Charles Miller, who was part of the Trump administration’s transition team for Nasa in 2017 and was senior adviser for commercial space at Nasa from 2009 to 2012, believes that such partnerships between Nasa and outside companies are “fundamental”. “Artemis is an opportunity to have a complete break with the failed space policies of the last couple of decades... to open up the solar system in a way that is completely affordable and could be transformational,” he says.

“If we go back to the moon in the way Trump wants and the way Obama did before him, by leveraging commercial partnerships, it can also be much faster and be of much more benefit to the world,” he adds. Miller, who is a serial space entrepreneur, says that if billionaires such as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are putting up capital and so “have skin in the game” it is a win-win, even if there have been some failures in the past.

"I think the overall strategy the Nasa administration wants to execute will succeed, the only question is when... The old model of the ‘big costs and aerospace needs’ is on the verge of collapse,” he says.

Dittmar, who is also chief executive for the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration, a trade group of more than 65 companies, sees things differently. She believes the space market needs to be at a tipping point where investors and company shareholders see the potential for returns and we might not be there yet. “I think public-private partnerships have a place, yes. Do I think it is a panacea? No,” she says, although it is more likely the market may be in shape by the time Nasa is looking at heading to Mars once the Artemis mission is complete.

For Dittmar, who was involved with work on the International Space Station (ISS), the implications of the Artemis mission are beyond business or even the limited scope that the Trump White House is projecting. She is looking for American leadership in space and being able to “keep the door open for others”. More than 100 countries have been involved in the various facets of the ISS mission both on the ground and in space and such cooperation will be crucial to make the most of the moon mission and beyond.

Dittmar remembers the 1969 landing and says that it represents “one of the shining moments in humanity on par with figuring out the Magna Carta”. But the full impact may not be felt for generations and it is the same with the new mission. “I do believe that other nations are going to be watching and thinking ‘what does this mean for us?’” she says. “Inspiration is not just public inspiration its inspiration in engineering, in technology development.”

“We are also going to learn about ourselves as human beings – being challenged by new environments,” Dittmar adds.

Conspiracy theories about the moon landing have dogged Nasa for decades, but Spellman believes the new mission is a chance to move beyond that. “We will probably have doubters when we go back [to the moon],” she says. “But to me it is so exciting to be part of it, it is tens of thousands of people that are going to be behind that capsule when it launches, the people that have got them there. It is exciting to be a part of it and if people don’t believe, it is unfortunate for them as it is pretty inspiring.”

Inspiration for the next generation is a key motive for Spellman, who has a young son. “We want this reality of working in maths and science to hit kids all over the world,” she says. “Now there is so much access to what we are doing – can you imagine the live feed coming from the moon and kids watching that? It will put it at the fingertips of children across the world and make it real to them that they could do something like this.”

In fact, Spellman hopes the Artemis mission will provide a cultural touchstone for everyone. “I hope the mission brings us all together, for at least a moment,” she says. "When you think about everyone sitting around watching their televisions or listening on the radio when Neil Armstrong was taking the steps on the moon, it would be great to have that moment again.”

“To inspire all the kids [and everyone] around the world to think the sky is not the limit, it is just the beginning.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments