Momo challenge: The real victims of the hoax are the parents who believe it

Momo is just another moral panic, and parents are falling for it once again. But, says David Barnett, the kids will probably be all right

Last week I received an email from my children’s school with the subject header: Momo – Please be Aware. The message warned of sinister videos targeting young people online which are “promoting children to do dangerous tasks without telling their parents (it threatens to hurt the viewer if they do not keep it a secret. Examples we have noticed in school include asking children to turn the gas on or to find and take tablets.”

Three hours later the school sent another email, saying that many parents had been in touch telling them that Momo was a hoax. The school pointed out that they were responding to guidance from the local authority, and that they have had pupils report Momo incidents to them verbally.

Well, of course Momo is a hoax. Because if it were real it would mean that some kind of supernatural being with exaggerated round eyes, a sinister smile and lank, dark hair was somehow infiltrating the internet and telling children to harm themselves.

Momo first came to prominence in July last year, when a YouTuber called Reignbot talked about some mysterious figure who was contacting teenagers via WhatsApp and other social media platforms. It was initially of the challenge variety; fulfil a task or series of tasks, failure to do so will result in harm or bad luck befalling you.

There have been many of these internet “challenges”. Some are just stupid; my kids one year talked endlessly of the baking soda and vinegar challenge – take a tablespoon of the first and then a mouthful of the second. Result? A small explosion in your mouth, and probably the risk of stomach ache if you were to swallow it. Idiotic, certainly, but probably not deadly.

But somehow Momo crossed over from being something that kids just laugh at into a global phenomenon. It’s a hoax, of course, but it’s more than that; it’s a full-blown moral panic.

Moral panics are not a recent thing, and they certainly pre-date the internet by a long, long way. Twenty years ago Kenneth Thompson wrote a book entitled Moral Panics; and he wrote: “It is widely acknowledged that this is the age of the moral panic. Newspaper headlines continually warn of some new danger resulting from moral laxity, and television programmes echo the theme with sensational documentaries. In one sense, moral panics are nothing new. For a century and more there have been panics over crime, and the activities of ‘youth’ in particular have often been presented as potentially immoral and a threat to the established way of life.”

Thompson cites cultural, music-based movements such as jazz and rock’n’roll, which were “said to be leading youth into promiscuity and antisocial behaviour” and, on a wider, societal level, how the 1950s saw “a panic about the effects on young people’s morals of spending time in coffee bars”.

As if popular music wasn’t impenetrable enough for parents, they had to go and look for hidden messages as well, which they were sure would lead kids down a road to damnation. Backmasking is a technique for recording sounds or vocals backwards, and often hidden among the mix. Perhaps the most famous urban legend of this kind is that the Beatles Revolution 9 contains the hidden message “Paul is dead”, leading to a rumour that McCartney was actually no longer with us.

There followed a spate of backmasking moral panics in the 1970s and 1980s... ELO – yes, they of “Mr Blue Sky” – were accused of incorporating a lengthy prayer to Satan on their album track Eldorado, while Led Zeppelin’s iconic “Stairway to Heaven” allegedly has a similar message. Even Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” apparently contains the hidden assertion that “it’s fun to smoke marijiuana”.

But the current round of moral panics, of which Momo is just the latest, play not directly on fears of breakdown of society due to youthful activities which the older generation just doesn’t understand, but are more finely targeted. And it is not the kids who are scared by Momo; it’s their parents.

Children have always believed in bogeymen, or at the very least gone along with stories that terrify and disturb, but then blow themselves out and are forgotten. Let me tell you about the Mad Monks. Back in the early 1980s, when I was maybe 12 or 13, a rumour began to circulate that in the cemetery near where I lived, on any given night, hooded figures would gather to perform what we only imagined were devil-worshipping rituals. This was absolutely true, by the way, because everybody said so and everybody believed it. It was just that no one had ever actually seen it.

Not through lack of trying, of course. Most nights for a couple of weeks that summer we would gather after dark and quietly tramp through the gravestones, in the hope of catching sight of the Mad Monks. All we saw were other groups of kids doing the same thing. Nobody ever thought to ask the pertinent question of why a group of devil worshippers would rock up to a municipal cemetery in the middle of a working class community on the outskirts of Wigan town centre in order to worship their dark lord Satan. Within a couple of weeks, the Mad Monks were forgotten and we found better things to do with our time.

The Mad Monks never became a moral panic because only the kids ever talked about them. And once we stopped talking about them, they were forgotten. Had anyone bothered to tell their parents what they were doing every evening, then it might have been a different matter.

Although Momo has been doing the internet rounds for the best part of a year now, it was only in February that it became a proper moral panic in the UK, and that seems to have been precipitated by the Police Service of Northern Ireland issuing an advisory on their Facebook page asking parents to be aware of the meme.

Then a mother from Westhoughton posted on a local Facebook group that her son had been in tears at school after watching a video featuring Momo and believing he was going to be killed. The story was picked up by the local newspaper, and the national tabloids weren’t far behind. Suddenly Momo was everywhere, was cropping up in the middle of Peppa Pig videos on YouTube, and even apparently insinuating itself into the hugely popular online game Fortnite.

That’s how a moral panic is born. Anxiety from parents fuelled by, usually, the tabloid press, which makes more people talk about it and perpetuates the myth. The fact that the mum from Westhoughton later said that her son had not actually seen the Momo videos himself after all, but had just been told about it in the playground, became lost in the welter of stories from the mainstream media inciting even more panic in parents.

In a way, it’s hugely understandable. Moral panics happen when young people get involved in something parents just don’t understand. And there is, of course, a dark side to Momo that plays on every parent’s fears that their child will harm themselves, fears that have been made more concrete by the very real problem of “advice” given online on how to commit suicide, which is something the social media platform Instagram moved to ban last month.

And, with the best will in the world, many people who are parents of teenagers will just not understand the internet as well as their kids. And Momo especially is just about recognisable enough to parents to cause anxiety, because the figure is redolent of a horrifying figure from the Japanese-originated horror movie franchise The Ring.

Released in 2002, The Ring was the first instalment of a series based on a 1998 Japanese cult horror, Ringu, in turn adapted from a novel by Koji Suzuki released in 1991. The story posits a “cursed” video tape, and anyone who views it will die within seven days, at the hands of a pale, lank-haired woman who crawls out of the TV set.

The similarities between the ghostly woman, Samara, and Momo are marked, and it’s unsurprising that the Momo image is actually lifted from a piece of sculpture called Mother Bird, created by a Japanese special effects company called Link Factory and on display at a Tokyo museum – none of whom are in any way involved with the Momo meme.

Maybe Momo was designed to play on those fears of parents, harking back to a horror film from their pre-child days, and coupled with the anxiety that for all their Facebook and Instagram use, they don’t really understand the internet quite as well as their kids do.

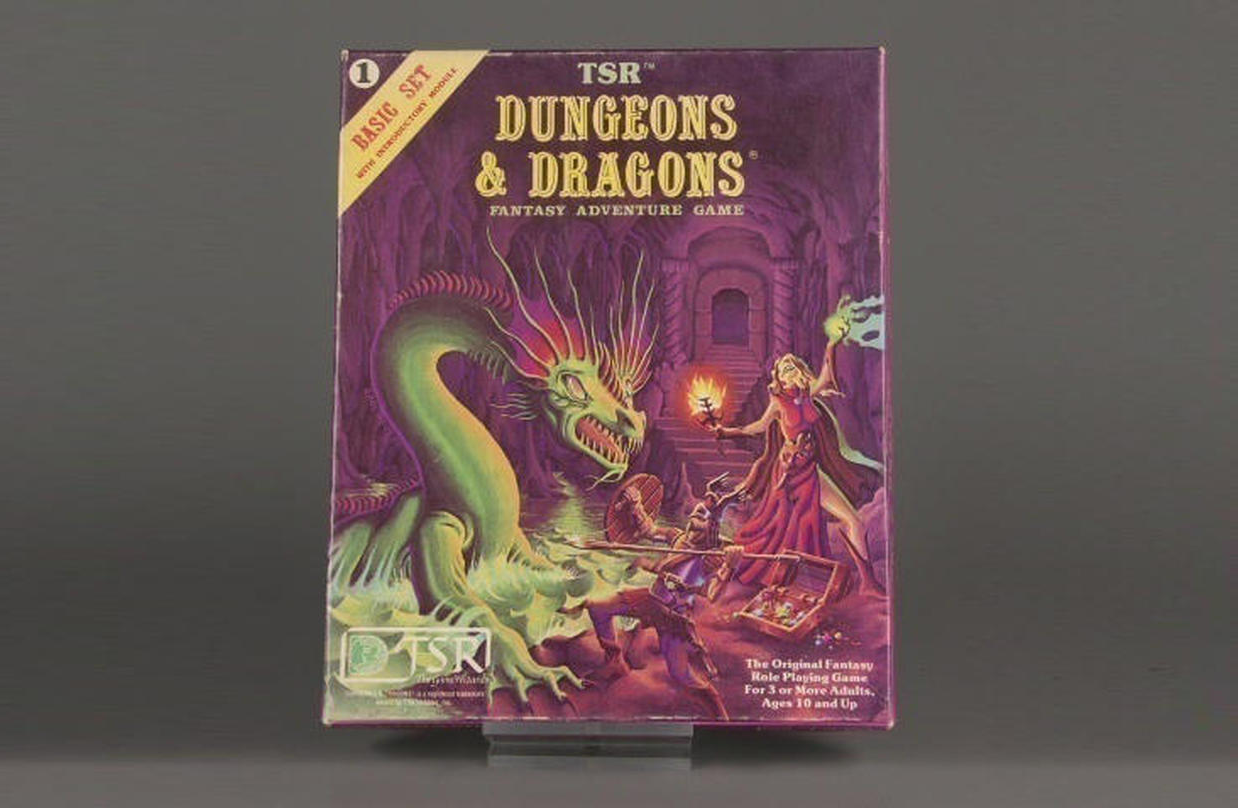

Back in the 1980s, around the time I was hunting for Mad Monks in our local cemetery, I was also enjoying roleplaying games such as Dungeons & Dragons. D&D allowed players to take on a character in a fantasy setting, becoming a warrior, or elf, or thief, or dwarf. Guided by a Dungeon Master, they would navigate castles and labyrinths and fell orcs and goblins on the roll of a set of dice.

Unbeknown to me, it was apparently also turning me into a Satanist.

Around that time there were two suicides in the States, young men who apparently had, between them, a raft of mental health problems and social issues. They also had in common that they played Dungeons & Dragons. One of the high school student’s mothers blamed her son’s death wholly on the game, and formed a pressure group called Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons (BADD), and the group was firmly of the belief that playing the game introduced young people to, among other things, demonology, witchcraft, voodoo, murder, rape, homosexuality, Satanic-type rituals, cannibalism, barbarism and blasphemy.

When the media picked up the story, a typical moral panic ensued, with parents banning their kids from playing D&D, often on one of the rather hazy and tenuous beliefs that were prevalent such as if your character died in the game, then you would probably commit suicide in real life.

Sometimes, moral panics can effect considerable change. In 1954, an American psychiatrist called Fredric Wertham published a book called Seduction of the Innocent which was an all-out attack on the comic books at the time. Wertham objected to the crime and horror comics especially, and even cast aspersions on the (as far as young readers were concerned, entirely platonic) relationship between Batman and Robin. He thought that such things were a direct cause of juvenile delinquency. Comic books were burned in the street, and a regulating body, the Comics Code Authority, was set up to ensure nothing unsavoury was published in comic books. Some publishers went out of business.

And things we now take for granted as received wisdom were instigated by moral panics and were just not true. Take the mods and rockers running battles of the 1960s, especially in seaside towns such as Margate. They have passed into legend, and it’s indisputable that there were such clashes. But not to the extent and scale that we believe they were. Indeed, it’s the way the media reacted to such events and indeed the whole concept of mods and rockers that fuelled the story. Indeed, in his book about the clashes, Folk Devils and Moral Panics, South African sociologist Stanley Cohen is credited with coining the term “moral panic” in the sense we use it today.

In 2014 two 12-year-old girls lured a friend, Payton, into the woods near their Wisconsin homes. They stabbed her 19 times, apparently in a bid to impress Slenderman. Payton recovered and the two girls were committed to mental health institutions.

What was originally a low-level occurrence grew and achieved a bigger status simply because of the media attention, argued Cohen. The moral panic created the thing it was most scared of. The myth was self-perpetuating. And that’s how moral panics develop and become, ultimately, self-fulfilling prophecies, especially in the internet age.

Take Slenderman. Momo’s precursor, for sure. Slenderman, a pale, faceless, elongated figure, was created on the internet community creepypasta a decade ago, as a bogeyman to appear in stories and artwork, and leaked on to the internet as a meme, a supernatural creature who would stalk and ultimately kill his victims, especially children.

The myth grew and altered, the more hands it passed through, until it was no longer just a piece of fiction created for entertainment, but an urban legend. And then it spilled over into real life in a quite horrible way.

In 2014 two 12-year-old girls, Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser, lured a friend, Payton Leutner, into the woods near their Wisconsin homes. They stabbed her 19 times, apparently in a bid to impress Slenderman. Payton recovered and a year ago the two girls were committed to mental health institutions.

Momo is perhaps the next evolutionary stage from Slenderman. Not a meme that has organically achieved its own status, but a more cynical and contrived attempt to circumvent the gestation period of a meme and go straight to the end result of moral panic.

It’s certainly worked, but has been without – so far – incident in the same way that Slenderman had. It’s already slipping down the news agenda, as quickly as it arrived.

Out of curiosity, I searched YouTube for Momo, and the infamous Peppa Pig video. It came up straight away, a few seconds of the beloved cartoon suddenly replaced by a photograph of the Momo character and a distorted voice telling me to go and get a knife and cut myself, and if I didn’t bad things would happen to my parents. It was crude and simple and had been thrown together in a few minutes by someone needing only a smartphone and the inclination to do it. Still, it was disturbing enough.

Despite myself not wanting to be drawn into the whole moral panic, when the letter arrived from school last week I felt duty bound to speak to my kids and ask if they’d ever “seen” Momo and if it had bothered them, and if so they could talk about it.

They looked at me in that way only teenagers can master which told me in no uncertain terms that I was an idiot.

Within a couple of weeks, Momo will be forgotten. There will be a new moral panic to replace it, that much is certain. But perhaps next time we might be more aware of the fact that the people who propagate such things are doing so in a way that seems calculated to press all the right buttons for a kneejerk reaction, parents will always err on the side of caution if there’s the slightest suggestion their children are in danger, and the tabloid press will gleefully stoke the fires for a few days at least.

The kids, meanwhile, seem largely to be the only ones accepting Momo and its ilk for what they are: minor diversions to be soon forgotten.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments