Inside the efforts to save Mexican wolves

Karin Brulliard got a rare up-close view of the mission to reintroduce critically endangered Mexican wolf pups to the wild this spring

In a private plane soaring 26,000ft over pine-swathed mountains, three tawny Mexican wolf pups sleep. Their weight is less than 3lbs each, their 10-day-old eyes still screwed shut. Their worth, as some of the newest members of a critically endangered species, is immeasurable.

The pups are protected by a soft pet-carrier and kept toasty – 25C, an attached thermometer indicated – by hand-warmers wrapped in a towel. They are flanked by a veterinarian and a zookeeper, chaperones for this leg of a precisely choreographed operation.

The pups were whisked from their birthplace, El Paso Zoo, two hours earlier. Their destination is the den of a wild wolf pack in the New Mexico mountains, where it is hoped the pups will be adopted into the pack, their genes bolstering an inbred population and helping to restore an apex predator and perhaps eventually providing a link in a chain of wolf populations stretching from Canada to Mexico.

Since the Pleistocene, wolves had populated what is now the US southwest and northern Mexico. But European settlers killed them off mere decades after arriving in the region, and now people are trying to make amends, with feats of logistics and technology. This is species recovery in the human-shaped Anthropocene, when an extreme extinction crisis is reflected in extreme recovery efforts – trucking salmon to cooler waters, wearing bird costumes to raise whooping cranes, and airlifting wolf pups to boost a wild population that has grown from zero to about 200 since a federal reintroduction programme began in 1998.

The Washington Post got a rare up-close view of the mission to reintroduce Mexican wolf pups to the wild this spring – one that involved dozens of humans in four states, transportation by golf cart, pickup, Cessna aircraft and backpack – and a lot of hope.

Risks to the pups abounded in the rolling peaks below, and doubts about whether all the effort was worth it flourished far beyond.

Conservationists have sued the government over its management of Mexican wolves, which they and researchers say ignores science and sets the animals up for failure. Ranchers argue that wolves ruin rural livelihoods. And humans remain an enormous threat – poaching, cars and encounters with cattle have caused the deaths of nearly as many Mexican wolves as the number that still roam the wild today.

The recovery programme is contentious enough in that the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which spent $2.8m (£2.39m) managing it in 2021, stopped introducing adult wolves, which ranchers and some officials say are more likely to be habituated to humans and to be aggressive. So, for now, the agency has placed much of its hope on the tiny, furred shoulders of “cross-foster” pups like the trio on the plane.

“Rarely is conservation so hands-on,” says Vikki Milne, the zoo veterinarian, over the blast of the plane’s air conditioning.

Milne means it. Soon, she is pulling on rubber gloves and reaching into the carrier. Newborn wolves do not urinate and defecate on their own; their mother licks them to stimulate the processes. For the next several hours, these wolves are between mothers – their birth mother in El Paso and their wild foster mother in New Mexico – so Milne will have to do it herself.

“We’re going to see if anybody has to potty,” Milne says, rubbing a cotton ball soaked in warm water between one pup’s hind legs. Its feet, studded with petite claws, stick straight out. It yawns, revealing a pink tongue. Its eyes stay closed.

Mexican wolves are North America’s rarest subspecies of grey wolf. They are smaller and browner than their Northern Rockies relatives, although scientists say it is likely they intermingled when wolves roamed the continent, before European settlement.

Deer may have been Mexican wolves’ main food source back then. But settlers’ livestock provided a new option, one that nearly doomed the canines. Across the southwest, they were hunted and trapped in campaigns often aided by the government. Their population dwindled.

The last wild wolves, five straggling survivors, were captured in Mexico and taken into captivity in the late 1970s. Later, two other captive wolves would be determined to have distinct genetic lineages. Every Mexican wolf alive today is a descendant of those seven wolves.

About 380 Mexican wolves live in zoos and other facilities in the United States and Mexico. They are inbred and, in scientific parlance, “genetically depressed”. The 200 or so in the “experimental population area” where the federal programme’s rules allow the wolves to roam, straddling Arizona and New Mexico, are even more so – on average, as closely related as siblings. In 2018, a federal court ordered Fish and Wildlife to better manage the wolves’ dire genetic state, which threatens their health, reproduction and long-term viability.

The agency’s main approach today is flying zoo pups – with their more varied genetics – to the high desert within two weeks of their birth, driving them into the mountains, hiking them to a wild den, placing them in a litter born within 10 days of the zoo babies, and hoping the wild mother “fosters” them. Dens are identified by GPS and radio telemetry data, which is available because about half of wild Mexican wolves wear radio collars.

The agency recently set a “genetic objective” of at least 22 cross-fostered pups surviving in the wild to breeding age, or two years old. So far, the agency says, at least 13 have done so.

The stars aligned for the pups from El Paso three days before their flight. Data indicated that two packs known as Iron Creek and Dark Canyon – whose alpha females had previously cross-fostered – had new litters. So, just before 7am on travel day, zoo employees gathered outside the Mexican wolf exhibit. Over the drone of rush hour, Tasha Bretz, the supervisor of the zoo’s Chihuahuan Desert exhibits, gave orders like a military commander, outlining steps to herd adult wolves out of the den area and swoop in to retrieve the five pups, which staffers had so far glimpsed only via the den’s camera.

It was the zoo’s second time participating. “Last year was a stellar career event for me, pups going to the wild,” says John Kiseda, the zoo’s buoyant animal curator.

“If we have anybody who looks like they’re not healthy enough to go to the wild, then we’ll have to set them aside,” Milne told the group.

One zookeeper lowers herself into the den, a hideout the litter’s mom, Tazhana, had dug into a dirt hill. Another ferries the pups out to Milne.

Working quickly, she and another vet sort them into crates – one for males, one for females. Bretz texts the field team: three boys, two girls.

Staffers put one male and one female back in the den, where, shortly, their mother would return to a smaller brood, a change that zookeepers say wolves seem to tolerate well.

Inside the zoo’s veterinary centre, the team place the wild-bound pups on an exam table. They check for fleas. They record temperatures, heart rates and weights. Milne places the pups on their backs to see if their “righting reflex” made them flip over. All was well.

“What else is on my list?” she says. “Body condition? Good. Nose is dry. Not swollen. Palate is good. Anus is good.”

Soon, the pups are riding in a pickup on Interstate 10 to the airport, where the Cessna Citation – piloted by a volunteer with Lighthawk, a flight organisation that supports conservation projects – waits.

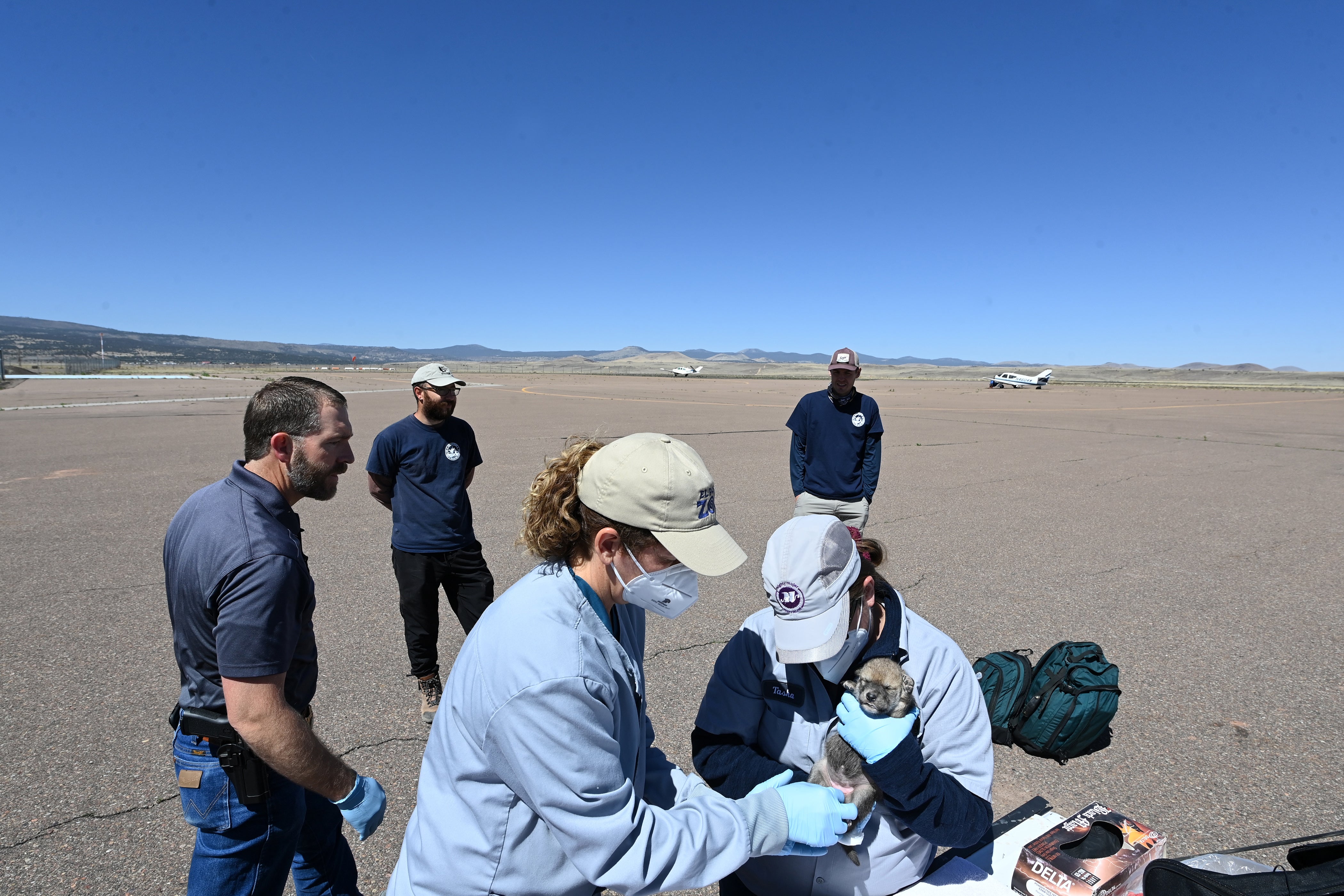

The plane lands about 300 miles away in Springerville, an Arizona town at the edge of Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests. An Arizona Game and Fish Department team was waiting, ready to help with the pups’ next step: a meal of puppy formula.

Reintroduction wasn’t always this way. The first 11 Mexican wolves released, in 1998, were three family groups. It was a rocky start: Six had been slain by the end of the year, according to an account by the recovery team leader. But over time, they bred – and spread.

Opposition in the states nearly ground releases to a halt between 2007 and 2015. During that time, scientists advising Fish and Wildlife recommended aiming for three separate US populations totalling 750 Mexican wolves, some of which would roam into Utah and Colorado, where Northern grey wolves have begun to reestablish themselves.

Governors of those states, as well as Arizona and New Mexico, hotly objected – publicly and in conversations with Dan Ashe, then-director of US Fish and Wildlife. In what Ashe called a compromise, the agency greatly expanded the recovery zone – but drew its northern boundary at Interstate 40, south of the Grand Canyon. Today, officials retrieve most wolves that stray beyond.

In an interview, Ashe says he thinks the wolves should be able to travel north: “Our recovery objective for wolves should be to restore a metapopulation.”

Suspending the release of adults was another compromise, Ashe says. But Ashe, who now heads the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, sees promise in cross-fostering – as a real-world use for zoo breeding programmes and as a model for other rare species, such as cheetahs.

At the Springerville airport, another Cessna lands. It has come from New York, flown by a volunteer who says he has previously ferried leopards, lynx and monkeys. His passengers are one nine-day-old female wolf pup, a veterinarian, and a keeper from the Wolf Conservation Centre in South Salem.

The New York pup will join the three from El Paso. Two will go to Iron Creek, two to Dark Canyon. These will be the final four cross-fostered pups this spring, bringing the total to 11.

The centre, its executive director, Maggie Howell, says later, was delighted the pup would have “the wild life that all wolves are meant to have.” But she would prefer to send bonded pairs and families - proven breeders who could contribute to the gene pool faster. The idea that 22 cross-fostered pups will make an impact “I think is misleading,” she says. Other conservationists and scientists agree.

Of 72 pups cross-fostered between 2016 and 2021, 16 have been confirmed to survive to their first birthday, Fish and Wildlife says, although the agency estimates that closer to 50 per cent may have made it. Of the 13 known to have reached breeding age, at least four have produced litters, and three more are breeding this year, officials say. The agency says those numbers, combined with steady overall population growth, mean cross-fostering is working.

“We’re showing biologically it works, and socially, it’s more tolerable to the people who live here,” says Paul Greer, Arizona’s Interagency Field Team leader for Mexican wolves, a star-shaped badge and a firearm on his belt.

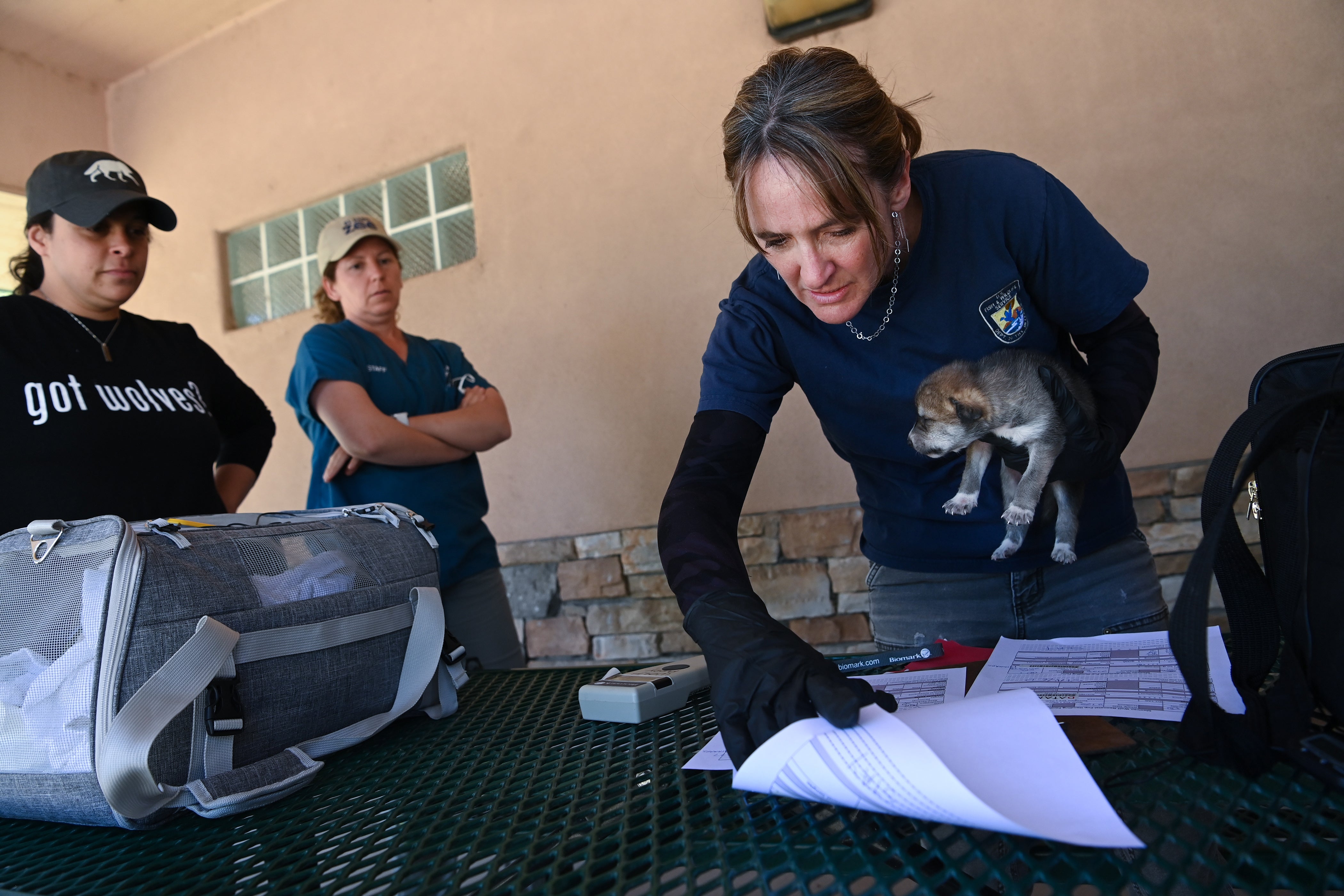

The next stop for the pups and their entourage: a desolate ranger station near Reserve, New Mexico, where they meet a Fish and Wildlife team from Albuquerque. At a shaded picnic table, agency veterinarian Susan Dicks examines the wolves, affectionately comparing them to baked potatoes.

“All right, I think this is the pair that will go to the Iron Creek den,” Dicks says, holding the smaller El Paso male and the New York female.

The teams set out again in a convoy of government pickups. On the winding road to Iron Creek, John Oakleaf’s dusty radio crackles with reports from crews already at the sites. Oakleaf, a Fish and Wildlife biologist, is the ringmaster of the cross-foster operations as well as point person for area ranchers, who are told when new pups are placed on land their cattle graze.

“I think the one thing we agree upon is that we don’t want wolves to kill cattle,” Oakleaf says as the truck bounces along. “Because that leads to removed wolves. Environmentalists don’t want wolves removed... and ranchers don’t want their cows dead.”

“So we all agree,” Oakleaf says. “In theory.”

Many ranchers aren’t fans of Mexican wolves. In a recent statement, the New Mexico Cattle Growers’ Association said the recovery programme was “being wielded as a tool to remove people from the landscape.” In May, Republican Representative Yvette Herrell, New Mexico, called for the destruction of a pack – whose alpha male was a cross-foster – that she said was “terrorising” ranching families.

The Iron Creek and Dark Canyon packs were chosen for cross-fostering in part because they are not known for killing cattle. Wolves’ diet is about 80 per cent elk, Oakleaf says, and about 10 per cent cattle.

Over the years, the agency says it has “lethally removed” 20 Mexican wolves for killing or bothering livestock. A new agency rule limits lethal removals, in part to prevent deaths of genetically important animals.

In response to a 2021 court order, the agency also pledged to better combat poaching.

Those steps are insufficient, says Michael Robinson of the Centre for Biological Diversity.

“Almost none of the 100-plus known illegal killings have actually been taken to court,” Robinson says. The agency, he says, “has delegated the destruction of endangered wolves to wolf haters.”

Despite the polemics, Oakleaf says he enjoys his job. He worked for a time with goshawks, he says, and “people didn’t really care.” That’s hardly the same with wolves. “I’m interested in trying to find that balance.”

Around 2pm, Oakleaf turns in to the staging area for the Iron Creek pup deposit, a clearing surrounded by pines. Two other trucks, one carrying the two pups, follow. He picks up his radio to tell the crew up the mountain that it’s time to find the den.

“Copy that,” a woman responds. “We’ll go ahead and start our search.”

GPS and radio telemetry data have given the scouting team a good idea of the Iron Creek den’s general location, and Allison Greenleaf, another Fish and Wildlife biologist, has a hunch it might be one the alpha female, known as AF1278, has used before: beneath the root ball of a downed tree.

She is right. As Greenleaf and a colleague get close to the site, the pack retreats, howling from atop distant logs.

Down at the staging area, the pups – which, like human infants, need to eat every three to four hours – are again being tube-fed puppy formula. One pup poops and Dicks reaches down to pick up the dropping: it, like all the urine and faeces the wolves produced this morning, will be rubbed on the wild pups. That will make all the pups smell the same, increasing the chances the mother will accept the newcomers.

“Don’t poop on my head!” Dicks says, laughing. “I’ve gone home with endangered species poop in my hair more than once.”

Soon, two team members are placing the pups, now known as mp2722 and fp2736, into a grey backpack. They take a short drive, then hike 20 minutes up a hill to Greenleaf and her partner.

“Now they have to live at least two years,” Dicks says, leaning against a pickup. “We believe they do great with the fostering, but then they are basically subject to whatever a wild puppy is subject to, living in the wild: other predators, disease, drought, famine.”

Shortly before 4pm, a radio broadcasts news from the Iron Creek den. “They found the den!” Dicks shouts. “There’s six pups in the den!”

Up the mountain, Greenleaf slides on her stomach into a sliver of space under the root ball, then passes the wild pups out to her partner through what she calls a “skylight” in the exposed roots. They place the eight squirmy pups on a red blanket beneath waving pines, checking all of them for their sex and condition, rubbing them with excrement and urine.

Within 30 minutes, the wild pups are back in the den, now with two foster siblings. Greenleaf slides back out, brushes off some of the dust that covers her, and fist-bumps her partner.

And that is it: less than 11 hours after their multistate and multivehicle odyssey began, the pups’ wild existence has started – one far different from their ancestors’. They might some day be fitted with radio collars. They will live outside zoo walls, but inside boundaries drawn and argued over by humans.

And they will be watched. This afternoon, the team will place a camera near the den, for monitoring the pups when they emerge to face the uncertain world outside.

Matt McClain contributed to this report.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments