Mehmet Aksoy: The life and death of British anti-Isis volunteer hailed as a Kurdish hero

Jihadis killed her son in Raqqa five weeks ago but the revolutionary spirit he embodied will live on in his mother. Casper Hughes talks to her about her son's life in Luton – and his other life reporting on the frontline

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Through the back door of a Luton convenience store, and down the steps into the patio-floored garden, Zeynep Aksoy leans against the brick exterior of her home and tells stories of her lost son. Arms crossed, eyes tired and intense, she speaks in Kurdish to an audience of Mehmet’s friends – some of them she is meeting for the first time and others she has known for years – all of them concentrated on her every word.

His mother for 32 years, Zeynep was the person who knew Mehmet best. She tells them about his innocent mishaps while looking after the family shop, his long lost girlfriends, the fun they had at his graduation and the bemusement she felt mingling among academics. She knew her son was special – like most mothers tend to feel. She was only to find out the extent to which others felt the same after he had gone.

The night before it happened, Zeynep Aksoy dreamt her son was shot in the heart. A day later, he was dead; shot and killed by Isis fighters in Raqqa, Syria, on 26 September. Mehmet Aksoy had been filming the YPG (People's Protection Units) liberation of Raqqa when a small group of jihadis (in what can only really be seen as a desperate suicide mission) drove into a YPG compound 12 miles behind the frontline, shooting him and three others dead, before all being killed in the ensuing gun battle.

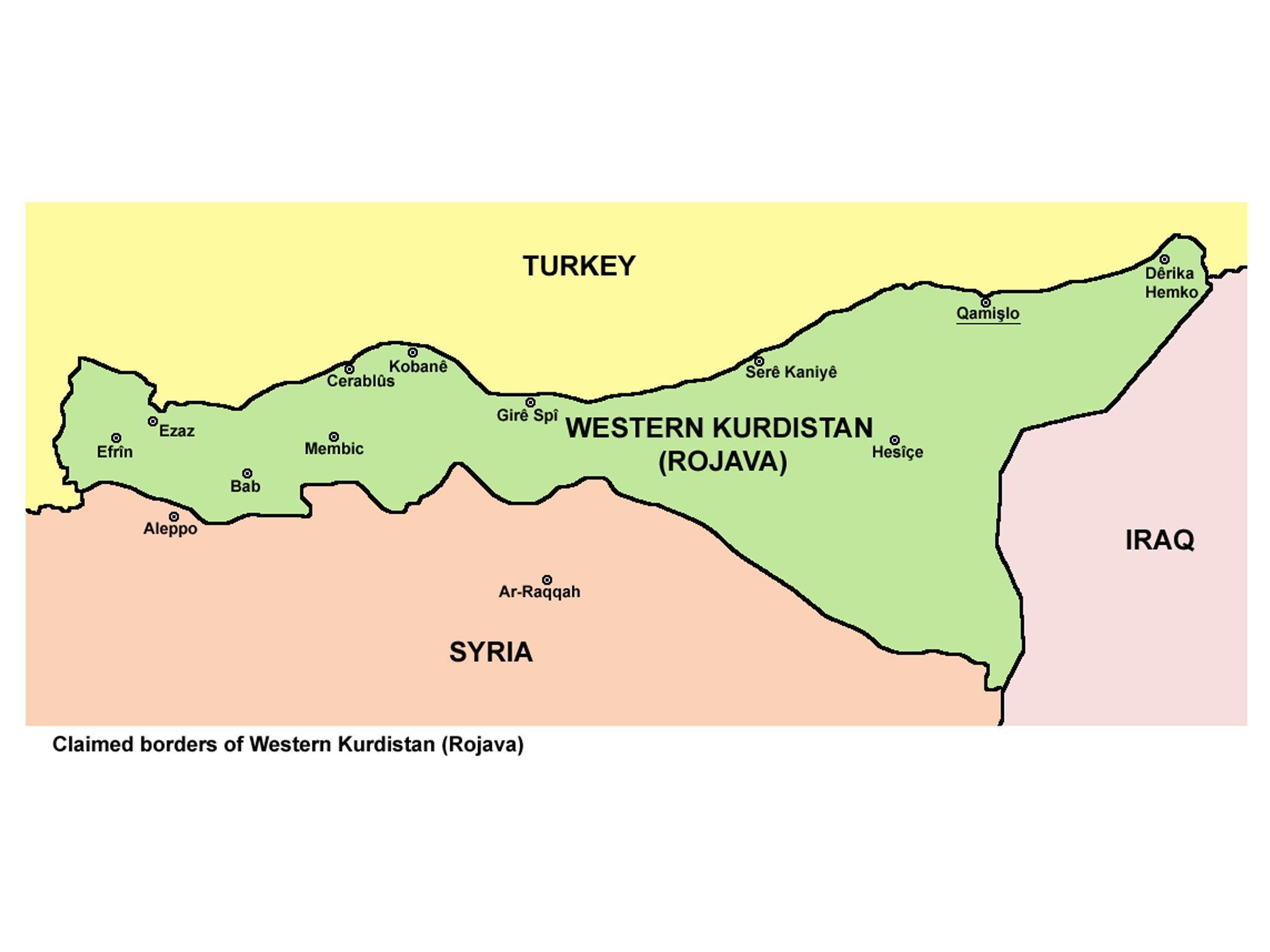

Thousands flocked to the Kurdish Community Centre in Haringey, north London, on the Sunday after Mehmet’s death. Thousands more Kurds, as well as the Arabs, Assyrians, Yazidis, Armenians and other international volunteers who make up the liberated region of Rojava in northern Syria mourned his martyrdom at a funeral held in the arid climes of Al-Malikiyah.

His mother, attending the packed-out nightly vigils at the community centre heard countless heartfelt eulogies to her son, and was repeatedly told by complete strangers how special he was. She later watched video footage of men and women weeping at his funeral in Rojava. Although she knew Mehmet better than anyone else, she had not realised how many people he had inspired and affected. There was a side to him she had not known.

Mehmet was three when Zeynep Aksoy and her husband, Kalender, moved to the UK from Malatya in southern Turkey. First in Hackney, then Enfield, and now Luton; they are one of the many displaced families of the Kurdish diaspora. His childhood was relatively happy, yet was typical of the immigrant experience in the UK. The family never had much money; and Britain never truly felt like home. A visit to the Kurdish community centre in his late teens, however, ignited Mehmet’s interest in the Kurdish independence movement, and put in motion his long journey to Rojava.

Giran Ozcan met Mehmet Aksoy at a Kurdish Youth Assembly planning meeting in 2004. “I remember telling my dad that night that I’d finally found the friend I was looking for,” says Giran. When they were first introduced, the two realised they had much in common. Young men born a year apart from one another, they had led remarkably similar lives. They talked to each other at length about the “traumas and experiences” they had undergone as Kurdish immigrants. Mehmet had found someone who could understand him. Thirteen years later, while Mehmet was in Syria, he would message his friend every day with his stories from Rojava.

“Mehmet was never fully content with life in the UK,” says Giran, reaching carefully for the right assembly of words to describe his friend’s restlessness. “He always knew he did not belong to – I don’t want to say the UK – but anywhere outside of Kurdistan, anywhere outside of the Middle East. He was never sure what would have made him happy, but he knew he wasn’t content with life here.”

This discontent was the topic of many of their conversations. They were able to understand it better when they talked to one another. Out of these discussions, however, what drew the two so close together, and would set in motion the events that led to Mehmet’s death, was a belief in a better world for their people. This is what motivated them, and made their bond irrevocable.

When he heard of his friend’s death, Giran flew straight back to London from Washington, where he works as the US representative of the HDP, the Kurdish left-wing party in Turkey. Sitting by a shrine to Mehmet in a marquee in the garden of Mehmet’s family’s home, Giran stares fiercely and gesticulates pronouncedly, as if trying to exude the monumental influence his friend had on him and the Kurdish community as a whole. Sometimes words fail him. But now, nearly two weeks since Mehmet has died, he is beginning to find the vocabulary to describe his friend.

“Mehmet wasn't just a guy who read Das Kapital, Volume II somewhere and thought you know what this is a good idea,” says Giran. “He was a born socialist. We would have fights over this, and I would criticise him for forgiving everyone. But this is the person he was: he gave everyone time; no matter how close to him they were, or how long he knew them for. He would always listen to people’s issues and try his best to offer a solution and give advice. He was a socialist in person and in the way he lived his life.

“And in 2004, when he first came to the community centre,” Giran continues, “he began to see that his values that were represented in socialism, were also represented by the Kurdish freedom movement.”

Mehmet’s introduction to the Kurdish freedom movement coincided neatly with the movement’s adoption of its exiled and imprisoned leader Abdullah Ocalan’s ideology of democratic confederalism. Aged 17, Mehmet read Blood In My Eye by the Black Panther George Jackson, a collection of prison letters excoriating the racism, imperialism and exploitation at the heart of America’s hegemony and championing black people’s role in overturning it, and began to question his own assimilation and the role of Kurds in British society. Another set of prison letters, Ocalan’s writings on democratic confederalism, were to become Mehmet’s blueprint for actively changing the world he found himself in.

Democratic confederalism was Mehmet's socialist principles put into action. Inspired by the work of and his correspondence with the renowned anarchist thinker Murray Bookchin, Ocalan had moved away from Marxist-Leninism and the Kurdish movement’s goal to create their own Kurdish nation-state in the Middle East and instead began to focus on an ideology centred on a confederated system of local autonomous groups practicing democratic participation.

On the receiving end of forced assimilation projects and massacres across all four nation states that Kurdistan encompasses (Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq), Ocalan viewed the problem of Kurdish independence to be one of the problems of nation-states themselves. The aim was to create a new kind of society where decision making would happen on a local level with women’s liberation and care for the environment at its core. Rojava in Northern Syria, liberated in the chaos of the Syrian civil war, and on the frontline against Isis, is a living, breathing example of this politics in action.

“The emphasis on radical democracy and on women’s freedom excited Mehmet very much,” says Giran. “As he read the readings of Ocalan, he just got more and more attached to everything that struggle stood far, actively taking part in organising his own community and teaching people about it, articulately in Turkish and English.” Mehmet became a self-appointed ambassador for the ideals of democratic confederalism and Kurdish freedom; a revered figure within the community known for his passion and lucidity on the subject. In 2013, after the YPG had begun to liberate Rojava, Mehmet started the website Kurdish Question as a way to spread the revolution’s reach and message to a digital audience. “He was able to interpret these ideas and implement them within the community,” says Giran. “That’s why thousands turned up to pay their respects.”

Another outlet for his restlessness, and a medium to express his thoughts, was film. Studying the subject at undergraduate level at Queen Mary’s, London, and then in a masters degree at Goldsmiths, Mehmet soon became involved in the London Kurdish Film Festival, entering his first short in 2005, before eventually programming the festival’s 8th and 9th years.

“For Mehmet, making films was a way to express himself,” says Ferhan Sterk, the co-director of the festival. Unsure of his own identity, and recently wrapped up in the politics of the Kurdish freedom movement, his films were a thorough investigation into the British Kurdish condition – “Mehmet was our connection between British society and the Kurdish community” – but also an attempt to reflect the reality of the perennial struggles of the Kurdish diaspora. But just as he wasn’t content simply diagnosing the ills of the Kurdish diaspora with Giran, Mehmet knew his skills could be put to use in the place that needed them most: Rojava. He wanted to present the revolution to the world.

For Ferhan however, Mehmet’s loss is monumental for both Kurdish cinema and the Kurdish community as a whole. “We lost the best director of Kurdish cinema’s time, who could change the future of Kurdish cinema,” says Sterk. “He had the talent, ability to connect with people and creative potential to do a lot of special things. He was our voice within British society. We don’t have that talent, we don’t have that skill. The only person who could do that was Mehmet, and we’ve lost him.”

Zeynep Aksoy knew her son was going to leave her. He was always disappearing. Never just content working in the shop, he was constantly back and forth from London, where he’d be working on one project or another. He even spent a time in Istanbul teaching English, and had moved to Germany for a while, where the levels of Kurdish activism were higher, and where more of the seeds for his eventual journey to Rojava had been planted.

While Kobane and YPG forces were under siege from Isis in 2014, Mehmet could be found pounding the streets of London, addressing rallies and demos with megaphone in hand, urging the international community to help the besieged city. If he wasn’t staying on a friend’s sofa, he would sit and wait for the barriers to go up at Blackfriars station so he could bunk the last train back home to the shop in Luton.

Mehmet never had any money, but he was never interested in things anyway. Sometimes Zeynep would plead with Mehmet to not leave, to stay with her at their home, to stop disappearing off to places without telling her where he was going. But he could not sit still, as he was dreaming of Rojava.

“I've said this to a lot of people,” says Giran Ozcan. “If he wasn’t content with his life for 32 years, every single second he was out there – and not just to romanticise what was going on in Rojava as he was critical too – Mehmet was the happiest he had ever been.” In their daily messages Mehmet would emphasise how the relationships “that had been destroyed by capitalism” were being revitalised in Rojava. Mehmet died weeks before the liberation of Raqqa, but in the three months he was there he was able to experience the solidarity and comradeship he had been looking for his whole life.

Aiming to show the Rojavan revolution to the world, Mehmet’s work was uploaded to the YPG press office Youtube account and shared across the globe. He posted regular videos of the YPG forces in action, the democratic processes of the region and fighter’s profiles which investigated the motives of the YPQ volunteers. “His gun was his camera. That’s what he held,” says Zeynep Kurban, a close friend of Mehmet’s since his early years at the Kurdish community centre. “One of the main reasons people are upset, even including his family, is because he was so effective at what he was doing, and was so very happy to be there.”

All of the skills he had crafted; the books he had read; the discontent that he had endured over the years had finally led him back to Kurdistan “in a spectacular way”.

“He went there knowing he could give as much as he could take,” says Giran. “And in the very short time he was there he gave a lot.”

Stood outside on her patio, Zeynep Aksoy talks about her regrets. She wishes she had got a phone. In the times he was away, she would miss Mehmet and scribble messages on a piece of paper for her daughter, Gonca, to text to him. But a phone would have meant she could have talked to him directly. She might have even seen the side to him that inspired so many people. She wishes she could have a few more years with her son. To experience life as he had experienced it, to be with him on his adventure.

At his memorial at the Kurdish community centre, cries of “Şehîd Namirin” (Martyrs never die!) ring out throughout the ceremony. Zeynep joins in, raising her arm aloft, making a peace signal with her hand, a gesture that represents the Kurdish struggle for freedom. As she chants, she can feel the revolutionary spirit he embodied. In the weeks following his death she has found out so much about her son, her best friend. She knows what he was fighting for now. She can see and feel what he gave his life for. Mehmet has gone. But she can now feel the side to him she never knew. She can feel his spirit. And it lives on in her.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments