Mass-Observation: How the social movement is still alive and kicking after more than 80 years

Tom Harrisson and co prepared the ground for a millennial resurgence in narrative and oral history. But can Mass-Observation be imitated? Godfrey Holmes goes people-watching

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When, in 1976, Britain’s brilliant, curious, eccentric, obsessive, unconventional, “Barefoot Anthropologist” was killed in a collision between his bus and a heavy timber lorry, Mass-Observation might well have died with him. But it didn’t.

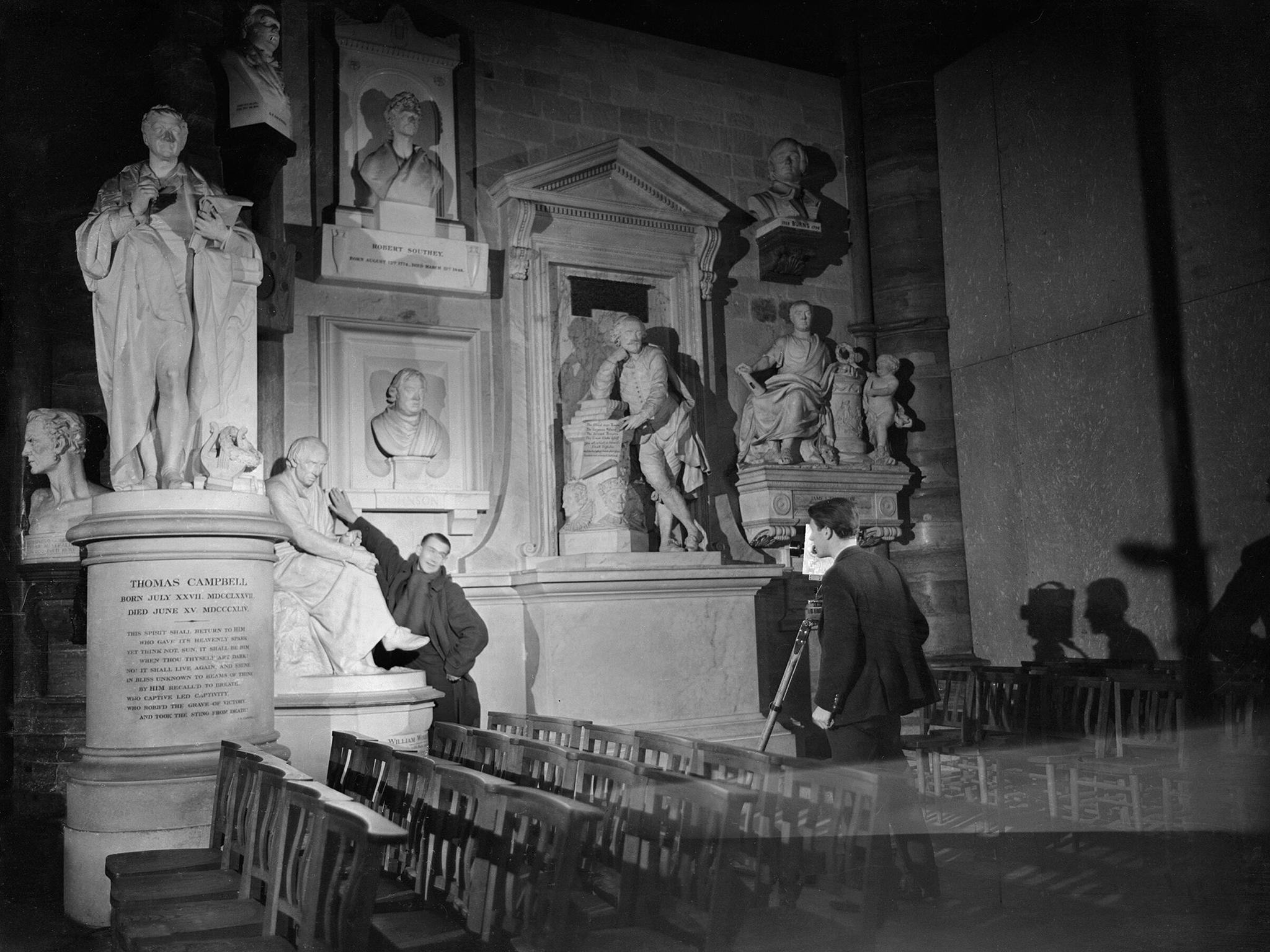

Newly back from Vanuatu, Tom Harrisson had founded the movement in January 1937 after the chance printing of his poem right next to sociologist Charles Madge and photographer Humphrey Jennings’ letter in the New Statesman appealing for more citizen observers.

By 12 February of the same year, 30 volunteers were on board to report back on their day. Only 3 months later, 12 May 1937, far more diarists were at hand to witness the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. And why was that occasion so significant? Mass-Observation’s moguls had suspicions as to how both the abdication and the succession were being interpreted by royalty, the press, and VIPs. Surely ordinary people would have a different take on proceedings.

Then the focus was on dance halls, quack medicines, Lyons’ Corner Houses, All In wrestling, bowling competitions, Bolton’s Girl Guides, funerals, the building of a new church, apprentices on strike, whatever. Within 18 months, Mass-Observation’s 1,730 descriptions of a day from sunrise to bedtime added up to 2.3 million words: not a few emanating from Strode Road, Fulham, 25-08-38.

Despite Bill Naughton of “Alfie” fame, Humphrey Spender – younger brother of Sir Stephen Harold Spender – and distinguished artist Julian Trevelyan coming on board, Mass-Observation, now humbly based in “Worktown”, Greater Manchester, could well have faced suffocation but for a coincidental rise in fascism, and the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939.

Duff Cooper, incoming minister of information, yearned for a tieup with the movement: off-the-shelf feedback on every topic from the Blitz to bacon rationing, from fire wardens to conditions in armament factories. Only so far was Tom Harrisson keen to proceed with this cooperation. After all, Mass-Observation’s midwives were sufficiently at war with each other without being labelled “Cooper’s Snoopers”.

Even in wartime, maybe because of the outside threat, there was no lack of students, clerks or housewives ready to fill in questionnaires and keep diaries in response to Harrisson’s most recent “directives”. A trinity of priorities: work-play attitude towered above the examination of certain more trivial aspects of ritual and custom, preoccupation or day-by-day survival mechanism. Volunteers consistently approached their task with energy, creativity and panache; accepting their anonymity; ever ready to make that leap from insider to outsider, outsider to insider.

Nor was it irrelevant that their taskmaster, Harrisson, had begun his diligence as Harrow School’s pre-eminent ornithologist; the only boy keeping a card index on every single teacher or scholar. Although all diaries for the crucial year 1941 have been lost, 3,000 boxes of notes, numerous radio broadcasts, and cuttings remain to form Sussex University’s priceless Mass-Observation Archive. Another magical coincidence: Sussex’s vice-chancellor from 1967 to 1976 was Asa Briggs, himself a renowned social historian.

So why has Harrisson’s “weather map of public feeling”; why has his “new science of ourselves” attracted such controversy, neglect, ignominy, ridicule? Baffling. Counsel for the prosecution is that by establishing their prime base in Bolton – in an untidy terraced house smelling of vinegar, fish and chips and unchanged bedding – Mass-Observation was slumming it. Oxbridge was condescending to a northwest region wilting in the Depression.

Furthermore, so-called investigators were no better than spies, pryers, nosey parkers, peeping toms, envelope steamers, keyhole artists, playboys… at worst, sex maniacs. Who else would bother about hand gestures, hat pins, suede shoes, door-to-door pedlars, mushy peas off the menu, toilet breaks, or chatup lines? Who else would chart exactly which part of a woman’s back a man held for the quickstep? Who else would pretend to sleep under Blackpool pier in order to count the number of Wakes Week affiliations, intimacies, embraces, copulations?

Further, the prosecution alleges a quixotic Harrisson – surrounded by “communists” and fifth columnists – first formed a conclusion, then recruited skivvies who would authenticate that supposition: hollow contometry dressed up as academic discipline. If photographing Bolton mattered in 1938, why had nobody addressed its welfare hitherto? If coal miners were suddenly to be interviewed at end-of-shift, why no inspector underground at start-of-shift? And if eavesdropping were – literally – to become the record, what makes Mass-Observation superior to the village gossip or titillated landlady – tumbler in hand – on the other side of cheap plywood door?

Now comes counsel for the defence. Jennings and Trevelyan went on to become outstanding in their fields of still photography, collage and filmed documentary. Meanwhile, Harrisson’s fellow poet Charles Madge – sometime journalist on the Daily Mirror – served 20 years as Birmingham University’s distinguished professor of sociology.

Furthermore, all those cardboard boxes of observations did translate into volumes such as May the Twelfth, Britain, War Factory, and The Pub and the People: the latter still probably still the finest study ever of public house life, charting the gulp, the slurp, the round, the etiquette of Friday night’s 7.5 minutes to drink a pint, Saturday night’s consumption of 3.45 pints per person.

Most to be valued: Tom Harrisson prepared the ground for a millennial resurgence in narrative and oral history, also some ambitious longitudinal studies: individual testimony no longer buried beneath crowd or statistically safer population – because the “Mass” of Mass-Observation originally referred to a mass of volunteers.

***

I wondered: could I imitate Mass-Observation? The movement itself was relaunched in 1981 to record great occasions like royal weddings – and still recruits diarists, respondents and citizen participants. Therefore, early in September 2018, I ventured into Bellport: my mission, on a bustling Saturday, to spend three-and-a-half hours in Bellport’s foremost shopping mall, three-and-a-half hours in the Bellport Arms: a good value 150-seat pub/restaurant.

Intriguingly, the St Lucia covered mall is also a thoroughfare – accommodating dozens of folk not consciously intending to buy anything. The posh, city centre end of this mall contains five fashion retailers, middle and back units more varied in their pitch: discount, catalogue, hobby, party. Key to any examination of customers: St Lucia’s “anchor” tenant is one of the “big four” grocers: on a Saturday magnet for anybody restocking fridge or larder.

Footfall is ever so important. My half-hour counting entrants yielded 22 lone teenagers, 10 groups of youngsters, 42 parent-teenager combinations, 56 young couples, 54 older couples, 36 parents accompanied by young child, 22 sets of 2 women, 14 sets of 2 men, shopping together, 146 lone women, 130 lone men. Later, patrons – predominantly male – in a sports shop specialising in expensive trainers outnumbered those in a quality footwear retailer not offering any reductions or inducements. But that shoe shop, as well as two clothes shops, retained customers longer.

Of interest, St Lucia’s cut-price card retailer did much better than its high end greetings competitor. Those entering a chain drugstore never looked to identify its branding. Quite clearly, shoppers knew their geography well enough to enter their chosen space as automatons; the exception being both toyshops. The interactive toyshop required much participation, so had more staff than customers – while its rival proved less forbidding.

Alongside my “big” surveys, undercover I conducted five smaller studies. Were shoppers eating as they walked from shop to shop? Not really. Two pensioners ate a biscuit on the move; two males ate sausage rolls; two young couples consumed a full lunch while ambling; three adults drank coffee; two teenagers, pop; one woman, milk; 12 people, bottles of water.

And were mall shoppers zombies, perpetually on their mobiles? Again, not really. Twenty-six males, 18 lone females, got phones out over a half-hour period. Crucially, only eight teenagers wore headphones; 28 shoppers in a pairing or group preferring screen to chat.

On leaving the grocer in search of their cars, a pattern developed: trolley unbagged, trolley bagged, trolley holding infant, half bagged, bagged, bagged, unbagged, own-bagged, bagged, own-bagged, half bagged, own-bagged, own-bagged, bagged, unbagged, bagged, unbagged, bagged, bagged, bagged, own-bagged etc. Depressing news for those welcoming a decline of single-use carrier bags: the majority of mall shoppers were still buying three or four brand new multiple-use carriers rather than bringing their own.

Paying for St Lucia’s car park proved fiendishly difficult – with almost every payer coopting upon another payer to help feed the machines aright. Eight meters were in a line: six occupied, then 2-1-2-4-1-2-2-2-2-2-3-4-5-3-4-3-4-0-1-2-3-3-4-5-6-7-6-7. In other words, Saturday morning kept the coins dropping.

Finally, while ensconced in St Lucia’s, I wanted to test my theory that very few shoppers wear bold, bright colours. Would drabness reign? During 15 minutes: 63 shoppers wore black, 61 darkish combinations, 16 fairly light colours, only six in white, 12 shoppers in navy blue, a creditable 35 bright or bold. Bright red was definitely out, bright green in; the 13 mustards far exceeding maroon or royal blue. In summary, mall shoppers dressed conservative.

***

Turning to the Bellport Arms, how on earth did I maintain complete cover? Clearly, for so long, surveillance within a smaller, hard-drinking establishment would have been rumbled. I survived by bagging a high stool just opposite the bar; by wearing a fleece with a cowl, by consuming only self-refill coffee; and by looking as if I was just waiting for a friend to arrive.

My two “big” pub studies were clamour for the bar, then bartender output. In between, I got a very good picture of a clientele heavily weighted towards ages 20-40; queue-jumping; males drinking vertically; most patrons spending only an hour per establishment; ordering liquid refreshment as opposed to burger and chips or steak pie; gin or sparkling wine for women under the age of 33. Dress: from wedding to casual. A single hen party wore 1930s’ striped blazers.

Over a full hour jostling at the bar: eight lone women were served; 20 lone men; 11 woman pairings; seven male pairings; 19 man/woman couples; three groups of three women; two groups of three men; one group of five women, two women with child, one man with child. Inevitably, some of these were returners.

On staffing, I started by charting stance. But that switched too frequently. Instead, for a whole sunlit hour I “followed” the diligent girl in specs. And diligent she was! Fifty-nine minutes passed before she paused to speak to a colleague. In the meantime, she dispensed 49 separate drinks and two meals. And not content with requests: on no less than 23 occasions, this bartender smiled and asked customers whether they needed serving! Eight times, those she asked were being seen to – so straight away she either cleaned surfaces or replenished stock. Never flagging, this young woman even removed a dozen used glasses to the kitchen. Nor forget her fitting in 20 complex cash/card payments!

On not slinking out of the Bellport Arms, I concluded: Tom Harrisson might be dead, but his baby, people-watching, is very much alive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments