Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream' speech is the greatest oration of all time

King combined reason and a simple plea for justice with a passion made all the more powerful for being so tempered by the quality of mercy and faith in peaceful progress

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some speeches are beautifully written, but poorly delivered. Other times we see naturally gifted speakers struggle with indifferent material.

Only a few master the gift of the extempore performance; and while every performer will make more impact if they have a suitably dramatic setting and an appreciative participatory audience, it is just a lucky few who are able to seize a moment so firmly that they can make not only the political weather, but even history.

A few “great” speeches never actually happened, though we wish they did – most obviously we might think of Shakespeare’s Mark Anthony, cleverly manipulating “friends, Romans, countrymen” to avenge the death of Julius Caesar. It’s doubtful the real Mark Anthony possessed such subtle linguistic skills as the Tudor version. Few modern speeches have much Shakespearean poetry about them.

On the criteria that might determine greatness, however, Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” address had everything. Indeed, there can be little doubt that it has a strong claim to be the greatest in the English language of all time.

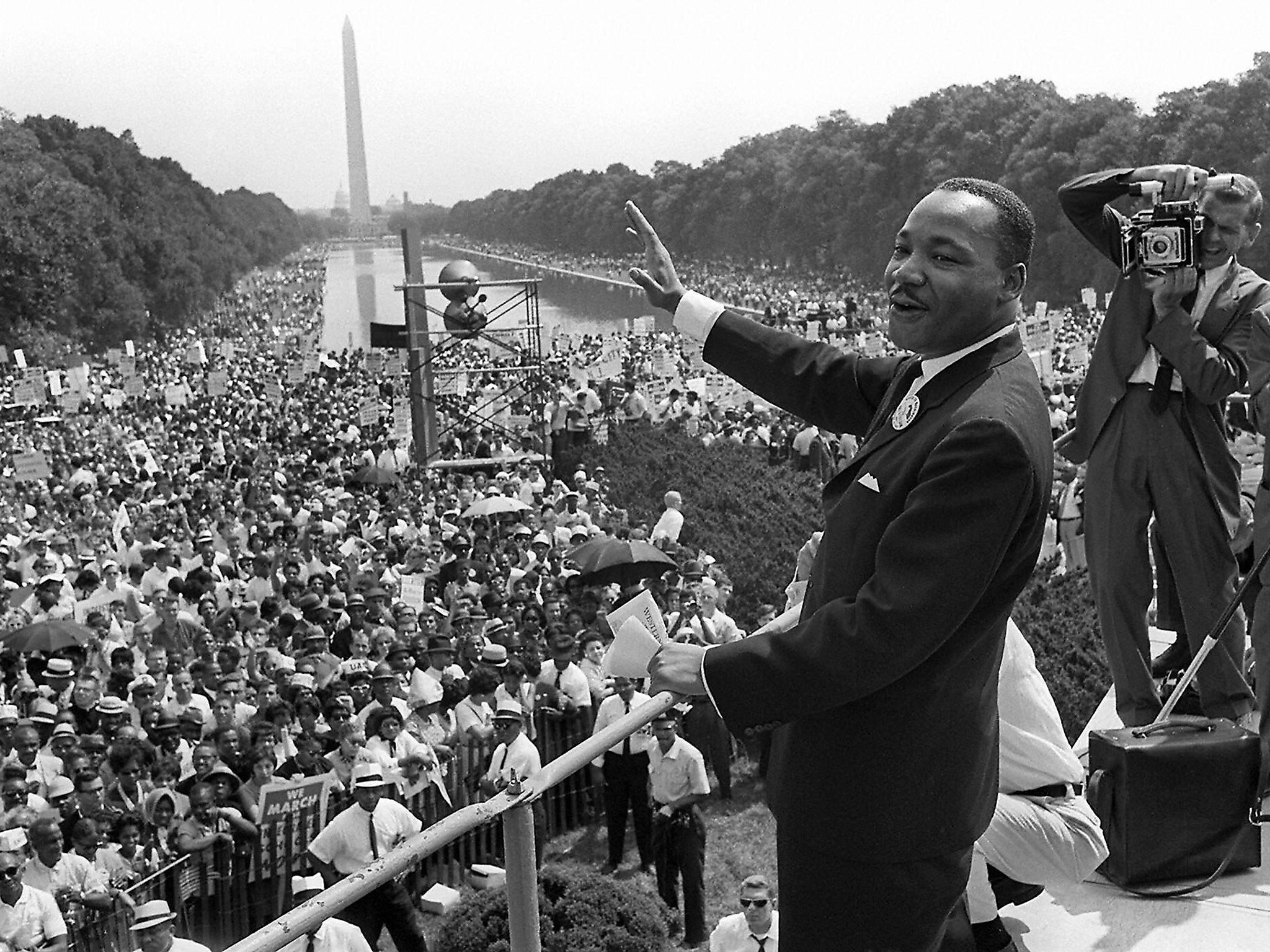

Take that setting, for example: speaking from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in the National Mall in Washington DC; the crowd of 200,000 or more; the speech as the culmination of a great march for justice.

Churchill had the House of Commons, Lenin the squares of St Petersburg, Kennedy his inauguration ceremony; but perhaps never before or since has such grandeur combined with dramatic expectation to such effect as that summer’s day in August 1963.

King knew too that he had an even bigger TV audience, and that his moment came at a time when the fight for civil rights was meeting a critical point of resistance.

As a kind of open air amphitheatre, the classical grace of the surroundings matched King’s habitual demeanour. Like Billy Graham, another with a background in preaching, King brought a dignity and power to his performances that was, one might argue, literally God given.

King also made the most of the human deity in marble sitting behind him: Abraham Lincoln. With great economy of language he reminded his audience that it was then five score years (a nice echo of Lincoln’s Gettysburg address inscribed at that memorial) since the slaves were set free, and promises of equality solemnly issued.

Since then, America had reneged on its assurances. From the 1880s onwards, Jim Crow laws at state level had restricted black voting rights and introduced segregation. The presidency of the otherwise saintly Woodrow Wilson produced federal level segregation in the armed services, post office and other parts of the federal machine.

Economic segregation was enforced by discrimination in the jobs and housing markets, including in the big northern metropolises.

The pernicious judicial doctrine of “separate but equal” was upheld time and again by the Supreme Court. Racism became a way of life: petty rules about sitting at the back of buses were commonplace; as were lynchings.

In this context, King used a plain metaphor – that the post-Civil War cheque issued by America to its black citizens had bounced, and now the time had come to honour the debt after so much evasion: “the fierce urgency of now”. The passages using the repetitive phrase “Now is the time” are among his most effective in the speech.

King combined reason and a simple plea for justice with a passion made all the more powerful for being so tempered by the quality of mercy and faith in peaceful progress – looked at now, we see not only the heir of Gandhi, but the precursor to Mandela too.

A bright boy growing up in segregated Atlanta, Georgia, King felt the injustices and indignities of the time as painfully as anyone. He was impatient for change, and fearful of what might befall America again if it did not arrive.

Still, without the support of the Baptist church and a place at a non-segregated university in Boston, even a man of King’s intellect and gifts might have remained a “boy”, kept in his place, so ingrained was racial prejudice in much of the US.

Through his preaching and assiduous study King became an accomplished and inventive orator. The picking up and slowing down of pace, the melodious delivery and the call and response with the audience – all very evident in “I Have a Dream” – were the natural product of the southern Baptist tradition (his father was also a pastor).

It is in fact a standard rhetorical technique to speak over applause and “bite into” audience “Amens” and “yeahs” to add to the climactic effect of key passages. This key element of delivery is not, of course, visible in the transcripts alone.

In the most rousing passages, King speaks over the audience’s delighted answers frequently; for instance:

“I have a dream that one day even the State of Mississippi, a desert sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression

Yeah Yeah

…will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice

Amen amen amen amen

I have a dream that my four little children

Amen amen yeah yeah

…will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their character.

Amen amen applause

I have a dream today

Applause

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama...

Applause

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory if the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

If such language wasn’t actually in the Bible, then it ought to be.

King borrowed freely from many sources to concoct a uniquely powerful cocktail of rhetoric. He echoed the Declaration of Independence as a “promissory note” for black Americans by which “all men would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. This was a smart move, not least in leveraging the potency of his case beyond the black community.

He was also perhaps inspired by Shakespeare’s Richard III – “This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent…” He cited directly the chorus from the patriotic anthem “My country ‘tis of thee” (the one that uses the tune to “God save the Queen”) and ended with the traditional Negro spiritual: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, free at last.”

Technically, there can be no doubt that the speech is a masterpiece, with countless three-part lists and two-part contrasts, and combinations of both devices, as in this example:

“When we let freedom ring... we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing... Free at Last!”

Although King himself was rightly contrasted with more militant civil rights figures and movements of the era, such as Malcolm X (who called King a “chump”), Nation of Islam and the Black Panthers, it is notable too that his advocacy of peace in the speech was subtly balanced with warnings of violence:

“There will be neither rest nor tranquillity in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.”

In assessing the speech, however, it is necessary to look beyond pre-planned rhetorical devices. Its real power stems from the sense that King was feeding off the atmosphere around him. It is said that when the Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson cried out, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin”, he was prompted to improvise that passage which reverberates down the decades.

He had used the construction before, in fact, but not with such epoch-making impact. Incredibly, it wasn’t in the typed draft he had before him that day.

King commented later: “All of a sudden this thing came to me that I’d used many times before, that thing about ‘I have a dream’ – and I just felt that I wanted to use it here.” What a decision to make, spurred on by Jackson’s words.

King’s was a speech by, for and with the people.

The Dream hit the world on 23 August 1963. Three weeks later, white terrorists bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, murdering four little girls in a crime that shocked even the segregationist South. Then, on 22 November, the President was slain.

At the time it must have seemed that King’s dream was being pushed aside by an American nightmare. But Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, refocused the momentum which had been gathering and pushed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act through Congress and into law by 1965, finally honouring Abraham Lincoln’s cheque of 1865.

Looking back at King’s most famous speech and his broader achievements, it is stunning to realise that he was only 34 when he “dreamed the dream”, a year older when he won the Nobel Peace Prize, and not quite 40 when he was assassinated after another historic speech in Memphis Tennessee (“I’ve seen the promised land”).

For a man so wise beyond his years, it seems strange to think that if he were alive today he would be 89, and would doubtless have even more service to his country behind him. That was stolen on the day he was shot.

And what, indeed, would King make of the United States today? Half a century on from the traumatic 1960s, some American states are eroding those hard-won voting and civil rights, and Donald Trump’s record on racial equality and respect speaks for itself.

Black Lives Matter is a modern day civil rights movement that should, if the advances of King’s day had been continued, be redundant.

It is good moment, then, to recall as well that it is not so long ago that Americans elected and re-elected their first black president.

Barack Obama had a way with words, too. At the dedication of the imposing Martin Luther King monument on the National Mall, with a sightline to the Lincoln memorial, he said something which is both sad and true:

“Our work is not yet done.”

***

Martin Luther King's “I Have A Dream” speech was delivered on 28 August 1963 in Washington, D.C. The words remain as powerful today as they were then.

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five-score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.

One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.

One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

So we have come here today to dramatise a shameful condition.

In a sense, we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a cheque. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.

This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of colour are concerned. Instead of honouring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad cheque, a cheque which has come back marked “insufficient funds”.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation.

So we have come to cash this cheque – a cheque that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquillising drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.

Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.

Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.

This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquillity in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds.

Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence.

Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvellous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realise that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. They have come to realise that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone. As we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?”

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied, as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one.

We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating “For Whites Only”. We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote, and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering.

Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification; one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with.

With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.

With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.

With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning, “My country, ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true.

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia! Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee! Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last! free at last! thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

* To register your interest in a forthcoming e-book from The Independent on the world's greatest speeches, please email customerservices@independent.co.uk, citing the subject line 'Speeches e-book'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments