How does an artist know when something’s finished?

The director who starts work on a play isn’t the same as the one who’s finished it, writes Margaret Heffernan. What would be the point of the work if it didn’t touch you?

When Olga Tokarchuk had finished her epic novel The Books of Jacob, she smoked a packet of cigarettes she had bought in anticipation of the occasion. It was a strikingly downbeat celebration for eight years of hard labour – “a reward”, she said, “for the phantom theatre director, now that the curtain had fallen.”

Finishing a work is a strange moment for artists. Gerhard Richter knows a painting is done when he has no more ideas of what to add or to destroy. But the moment often catches him by surprise; sometimes, he says, he will work away at a picture over and over again, worrying that it will never be a good painting, when suddenly: it’s done. And he’s pleased.

For Anselm Kiefer, the opposite is true. It’s a hard moment. He isn’t very interested in the end stage, the moment when future possibilities are few. Surrounded by containers of his work going back 50 years, Kiefer doesn’t think about art as a neatly managed project. It’s fluid, he says, a river, never finished, always in process. He sometimes puts his pictures out in the sun or the rain – and the pictures continue to evolve as he leaves them there. The reluctance artists often feel to conclude their work recognises that uncertainty, the puzzle that drew them in, might now be reduced – the work is what it is – but doubts remain.

For Mahler, that uncertainty went on for years as he cut, rewrote and rearranged his First Symphony. Its poor initial reception might have been one provocation – a sense that the audience didn’t understand what he’d written. But in the changes he made, crowd-pleasing isn’t the driving force. There’s an energy in the work that Mahler tries and tries again to set free.

No piece is ever finished; it’s just waiting to be accepted, rejected, interpreted, or rediscovered. Tokarchuk writes what she calls “constellation novels”: composed of fragments of incomplete stories the connection between which is neither didactic nor obvious, but elusive, for the reader to connect – or not. In this way, the book isn’t finished until readers arrange the constellations in their own minds. The very strangeness of their configuration is what makes the books so memorable and so personal; it’s hard to imagine that any two readers could have the same experience of reading them. They carry on, in memory, non-linear, provoking questions, defiantly refusing to end.

Tokarchuk isn’t the first writer to deny the connective tissue that explains – TS Eliot did much the same thing in The Waste Land. But her novel Flights is a radical experiment in how much narrative a novel can do without, a beautiful and elegant rejection of our instinct that if a story is coherent, then it must be true. Surveying people in flight – from life, on planes, running away from home or travelling towards the unknown – its multiple, non-linear perspectives resist our compulsion to reduce human complexity to simple, comfortable banalities together with logical linear endings. Wisdom is embodied in lost and dejected characters; madness comes from the mouths of authority figures. All wrench us out of narrative tropes that come between us and a raw, unmediated experience. Flights bristles with uncertainty and dares us to live with it, relish its freedom and the truth of its contradictions. And so the book lives on, in our heads. “Fiction is as close as you can come neurologically to someone else’s reality,” Margaret Attwood says – because it’s participatory.

In just the same way, Lubaina Himid considers visitors to her exhibitions not as voyeurs but as participants; she aims to encourage agency in us, of the kind that creating the works in the first place required of her. Like Toni Morrison, she hopes to enlist active “co-conspirators” in a new way of seeing the world.

Of all the art made, what will last? You’ve only to glimpse the much-touted authors advertised in the back of old books, or to attend an art auction full of once-cherished paintings, to see how quickly and randomly success evaporates. But the opposite is also true: that the times rise to meet work that was previously disregarded. For nearly 200 years, King Lear was more or less forgotten, deemed too dark and miserable to stage – until the post-war period when suddenly it seemed the ultimate articulation of what we had discovered about ourselves. For 300 years, Caravaggio was dismissed as vulgar, lewd and impious. One of his greatest paintings – the Supper at Emmaus – ended up in the National Gallery only because it failed to sell at auction. Yet today, tourists make pilgrimages to Naples, hoping for the chance to see just three of his pictures. His hookers, hustlers and card sharps are now celebrated for the reality and drama they impart to scenes that feel as accessible as outtakes from movies. And, after all his alterations, Mahler’s First Symphony is frequently cited now as among his finest.

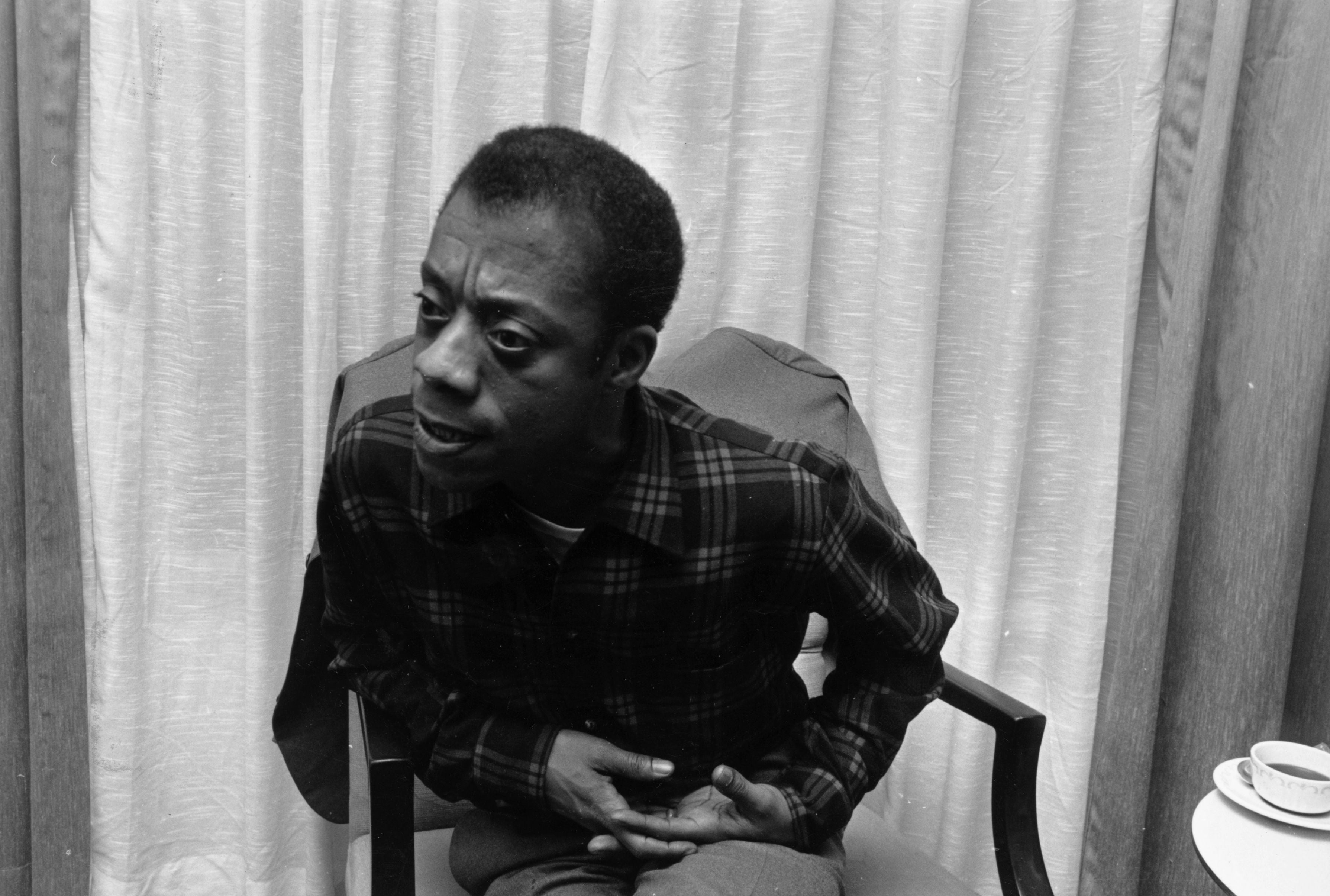

Artists themselves know this. In the 1980s, when much of the world seemed to feel that the drama of the civil rights movement was over, James Baldwin recognised he’d been left behind. But even his journalism had never been just about a moment in time. He had always dug deeper, seeking to reveal the cancer at the heart of the American dream. And so the work lay latent, ready for the moment when America and the world had to confront again the fantasies and illusions that perpetuate racial hatred and violence.

Baldwin’s quiet confidence amidst the hurly-burly of fashion and fads doesn’t make artists infallible judges of how their work will be received. Co-conspirators, after all, have minds of their own; uncertainty about how their work will be received keeps failure always in mind. When Sebastian Barry finished his novel, Days Without End, he sent it to the publisher with the thought that it would certainly fail, the public would not buy it and therefore he would need to write another book fast. In fact, it made him the first author to win the Costa book award twice. Artists live with failure: in their minds and in the public arena. It’s hard to tell which is the tougher test.

But they don’t give up. The playwright Peter Barnes once told me that when two huge plays – The Bewitched and Laughter! – were met with outraged rejection, he decided to start over, to put his game back together, like a golfer. He began with monologues, then dialogues, then trios: a deliberate act of renaissance. Seven years later, his play Red Noses took London theatre by storm: still recognisably his work, with its surreal humour and rigorous insight, but richer and more complex. All he’d hoped for was better, not best and never perfect. Who would want perfect? Perfect would be dead. “A perfect poem is impossible,” Robert Graves wrote. “Once it had been written, the world would end.”

Instead, and often to the outrage or bafflement of their fans, artists change. Gerhard Richter has turned to sculpture, Lubaina Himid has started working with sound. Louise Bourgeois moved from painting and prints to huge metal sculptures. Such changes are driven by curiosity, the urge to keep exploring. Schoenberg’s admirers were appalled when he abandoned the plangent lyricism of Verklarte Nacht for the 12-tone scale and many of James Joyce’s staunchest devotees baulked at Finnegan’s Wake. Olga Tokarchuk left the sprawling ambiguities of The Books of Jacob for the relative structure of a crime story. Furious Miles Davis fans have never forgiven his electric years, while it has taken decades for Bob Dylan enthusiasts to appreciate that change is the point: that the developing of self is Dylan’s subject. “If the work has brought you from one place to another,” Baldwin said, “you’ve arrived at another point. This then is one’s consolation, and you know that you must now proceed elsewhere.” Abjuring certainty, the artist sets off, again, to explore new territory.

The director who starts work on a play isn’t the same as the one who’s finished it. What would be the point of the work if it didn’t touch you? Art isn’t an escape from the world but a deep dive into it. “Ninety per cent of me has changed,” Tracey Emin says. “I want to see new things.”

This flies in the face of the way that we are routinely urged to think about ourselves: to develop a brand, “Brand You” turning unique talents into winning but static formulae. The industrialisation of self – aided and abetted by apps that can monitor and measure us – is the ultimate articulation of a desire that, instead of human beings with all the fluidity required to adapt and respond to uncertainty, we should aim to nail ourselves to the flag of our choice and promote it unwaveringly. It’s frightening to think just how absurd and degrading this is; Marx called it reification, the turning of humans into commodities, as though we were all so many detergents jostling for space on a supermarket shelf. But it is also the antithesis of the value, meaning and joy that we find in front of a great painting, immersed in a book of fantasy and imagination, untethered in a sound cloud of emotion.

Art that lasts isn’t selling us anything. The historian James Shapiro commented that you can scour Shakespeare as long as you like, you will find no ideology. What draws us back, again and again, is a rich dialogue between artists and ourselves more intimate and complex than daily life typically affords.

No brand manager would ever have conceived of reopening the Sadlers Wells opera at the end of the Second World War with a piece of such dark complexity and ambiguity as Peter Grimes. And yet, “by the time you are done with the opera” the critic Edmund Wilson wrote, following its premiere, “or by the time it is done with you – you have decided that Peter Grimes is the whole of bombing, machine-gunning, mining, torpedoing, ambushing humanity which talks about a guaranteed standard of living, yet does nothing but wreck its own works, degrade or pervert its own moral life and reduce itself to starvation."

That art digs so deep doesn’t mean it’s without political content. Capturing the zeitgeist, it can change our perception of where we are: what Ezra Pound called “news that stays news”. It provides bridges, connections through which we can experience the arguments, fears and torments of our age through intimacy with other minds. Art lasts not because it nails down human experience but when it refuses to do so. Which is why authoritarian regimes fear artists, and why their citizens look to artists to be their truthtellers. Not for the simple, linear, predetermined narrative, following familiar paths. Not by abjuring uncertainty. But for the open road.

This is an extract from BBC Radio 3’s ‘The Essay’ – you can listen to Margaret Heffernan on art and uncertainty on 9 January 2023

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments