Ghost towers: What does the future hold for London’s unoccupied flats?

The capital has become filled with tall glass and steel ‘icons’ that are conspicuously unsold or ‘owned and left empty’. For decades protesters have demanded they be repurposed as social housing. Oliver Bennett unravels the highs and lows of a phenomenon with global foundations

Centre Point must be one of the most divisive landmarks in London. Erected in 1966, it instantly dominated the West End and while some celebrated it – architect Erno Goldfinger called it “London’s first pop art skyscraper” and amazingly, likened it in spirit to The Beatles and Mary Quant – the brainchild of reclusive developer Harry Hyams has had a mixed reception over its 52 years.

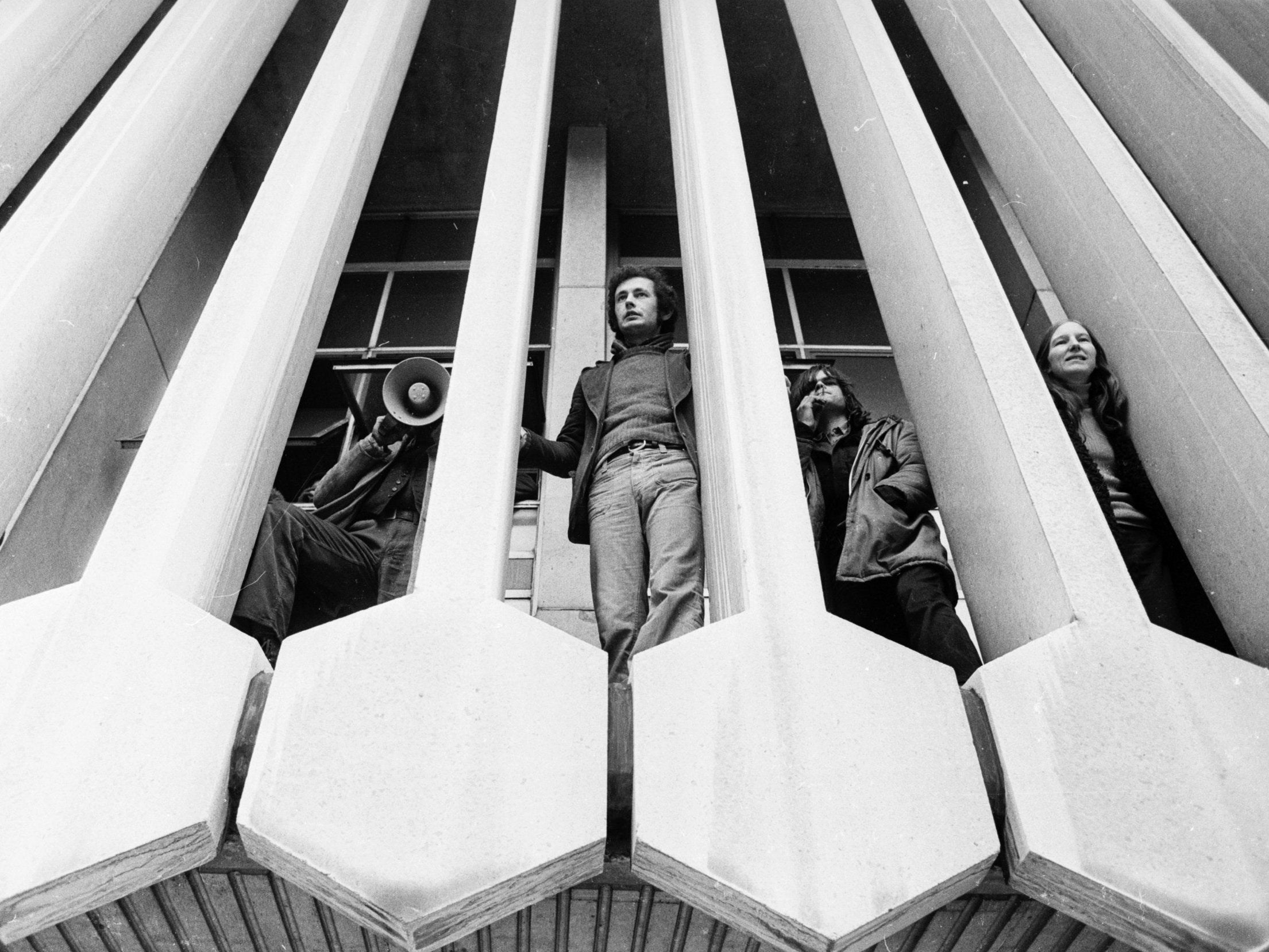

But perhaps Centre Point’s most curious fate has been to remain more or less empty. It never fully worked as offices. In 1972 Camden Council tried to requisition it. Harold Wilson wanted to nationalise it. It was occupied for a weekend by housing activists in 1974 – one was Labour politician Jack Dromey, Harriet Harman’s husband. A major homelessness charity was named after it. Then a Grade-II listing and a recherché desire for Brutalist icons (it came from the feted drawing board of Richard Seifert’s master architect, George Marsh) bought its zig-zag façade back into favourable view and it become luxury flats, synced to the new Crossrail development. What could go wrong?

Well, the Centre Point curse has struck again. In October its developer Almacantar decided that offers on its remaining luxury flats were “derisory” and “detached from reality”, and decided to take them off the market. So Centre Point has now cemented and updated its footnote in London folklore as one of the capital’s benighted “ghost towers”.

From Centre Point to the Shard, from Battersea Power Station to the sky-reaching baubles of Nine Elms – even in The Independent’s old neighbourhood in City Road – the past six years or so has seen London become filled with tall glass and steel icons that are conspicuously under-occupied: built in a time of optimism for an overseas market and now languishing unsold or OLE: owned and left empty.

The problem is that housing is an extraordinary failure of the market. It’s an oligopoly that controls the supply

The immediate prognosis is not good. It has been said that half the 1,900 luxury apartments built in London last year failed to sell, and it’s estimated that there are around 2,500 to 3,000 unsold but complete luxury new builds, with many still entering the market. Property analyst Molior London noted that sales of new homes in London fell by a fifth last year, and that the number of unsold apartments continues to grow. And the more expensive they are, the more likely they are to be unoccupied: 39 per cent for homes worth £1m to £5m, 64 per cent for those places over £5m. There are reports of people trying hard to sell and to complicate matters, there’s the impending known-unknown that is Brexit.

* * *

It seems an odd characteristic of the past 10 years that things have been so difficult for buyers in one direction and so easy in the other. These luxury apartments are commonly between £1,000-£1,500 per sq ft, against the average UK price of £211 per sq ft. But, their posh locations aside, one of their key drivers has been the post credit-crunch migration of capital.

“We’ve seen an era of low interest and cash into assets,” says Henry Pryor, a property-buying agent. “When money is unsafe, or doesn’t inflate, the rich put it into other things: cars, art, houses.”

The high-water mark was about six or seven years ago when then mayor Boris Johnson went on a spending spree and encouraged others to do likewise. London became what Pryor calls a “speculation paradise” – and that spike is now heading in the opposite direction.

So, if housing is a free market that can go up as well as down, why does Almacantar not take the hit with its Centre Point flats and sell them for less? “It doesn’t work like that,” says Michael Ball of the Waterloo Community Development Group and a seasoned housing activist. “The problem is that housing is an extraordinary failure of the market. It’s an oligopoly that controls the supply.”

The seeds of the current zombie-tower wobbles came with George Osborne’s stamp duty reforms in 2014, which took the froth off the market, leading to developer grumbles – wasn’t he one of us, they wailed? Then the long lead-time of developments began to show as a significant constraint, for as well as “skyscraper syndrome” (where a glut of tall building supposedly presages a downturn) there’s also the problem that many developments are financed by upfront sales.

“Many were designed to be sold off-plan to release capital for building,” says Roarie Scarisbrick of Property Vision. “Now people are waiting until properties are actually built, which squeezes developers badly.” Increased scrutiny on money laundering may also play a part which, as Pryor says, “is still too easy”.

Plus, some high-end properties were simply never meant to be lived in but just to be “gold bars in the sky” as Ball puts it. It’s hard to find out how many of London’s luxury flats are truly unoccupied. “You can look at census, but it’s tough to find out numbers,” says Ball. “I don’t think we know the extent of it. The records are really poor.” And as ever with property, the winners crow and the losers remain silent.

* * *

There are a few other factors to observe, including the move of real estate into a high-end branded fashion buy, as the Candy Brothers did with their developments. “That aspect took me by surprise,” says Pryor. “It turned out that people wanted to be able to specify that they had a Candy apartment as they sat in Monaco, as if boasting about owning a Bulgari watch or a Montblanc pen.”

There’s also an argument that some parts of London, such as Eaton Square in Belgravia, have long acted as pieds-à-terre for the rich and were probably ghost-like in the 18th and 19th centuries. “Remember, in Downton Abbey they occasionally come down to ‘Grantham House’ in London,” says Adam Challis, head of residential research at real estate company JLL.

“That old ‘country seat and the London house’ combination is now a global rather than national phenomenon, and a London apartment became part of a wider property portfolio.” He points out that while these spectral apartments may appear unoccupied, it could well be that their ultra-rich owners may only use them for six to eight weeks a year.

I sometimes wonder what would happen if all the owners turned up at once to these places. It would be a disaster

Nine Elms is a typical new London “owned and left empty” zone. A swathe of land between Battersea and Vauxhall, it was a low-value industrial hinterland dominated by the Cold Store – a piece of charismatic dereliction used in an episode of The Sweeney – and the only respite being London’s flower market. Now it’s a parade of gleaming hi-tech towers.

“When private developers get hold of the land it leaps in value tenfold,” says Michael Ball. So in a way, however many apartments have been sold here, it may have already fulfilled its profit promise. Sometimes, adds Scarisbrick, such places are not even designed for full occupancy. “I sometimes wonder what would happen if all the owners turned up at once to these places,” he says. “It would be a disaster.”

There are precedents to all this. In earlier eras luxury housing went up as well as down, and lost out to new tastes. Michael Ball says that St Georges Buildings in the Elephant and Castle area was built as a luxury development in the 1880s. “By the post-war era it had become squatted, then became social housing. Now it’s luxury housing again.”

Peter Murray of New London Architecture (NLA) cites the Bedford Estate and the Foundling Estate, both built in Bloomsbury in the late 19th century. Only the former became fashionable while the latter, built just a couple of years later, “became what we’d now call a ‘sink estate’”. So all kinds of transient factors depress the market and it’s reasonable to assume that some of the new developments will work, while others will look tawdry in the years to come.

* * *

The ghost tower phenomenon isn’t confined to London or the UK. There are similar qualms in South Africa, Canada, New York and Mumbai, where a string of luxury skyscrapers in the Worli and Prabhadevi districts have recently struggled to find buyers. Emptiness is a fact of life in the construction industry and just last month it was reported that a fifth of China’s new housing is empty: an extraordinary total of 50 million ghost homes. But another aspect of construction, says Challis, is that it attracts “huge economic growth. So empty homes are an endemic feature of the world’s most important cities.”

The extent of London’s ghost towers may even have been overestimated. “Evidence from the LSE for Sadiq Khan showed that unlived-in apartments were actually under 1 per cent of new build properties,” says Peter Murray of NLA, who adds that London properties are still selling well in Singapore and Hong Kong. Meanwhile, London has 510 tall buildings in the pipeline: up from 455 in 2016. Even with its current depredations, property in London is still considered a safer bet than many financial vehicles.

But there’s no doubt that ghost towers fail the political and social smell test: as visible reminders of disposable wealth in a city where most can’t get a foothold.

“They raise questions about the wider economic gain that they bring,” says Challis. “Obviously people are uncomfortable with such ideas, though.” So some local authorities are looking at ways of designing them out. Challis says that Vancouver effectively kiboshed its own ghost towers by bringing in a 15 per cent transaction tax, later raising it to 20 per cent.

More recently Westminster City Council decided not to approve applications for luxury flats over 1615 sq ft. “We want Westminster to be home to thriving, mixed communities, not empty super-prime properties,” said its head of planning Richard Beddoe. As for home “flipping” – buying and selling quickly for rapid gain – you’d be a sucker to try that in London at the moment.

So, given that ghost towers and unsold luxury flats currently exist, whither their luxurious wenge-floored acres, gyms, pools and media rooms? Will developers have fire sales just to get rid of them? (Molior London has said that 10-15 per cent reductions are typical and 20-30 per cent reductions achievable, and that it would take more than three years to sell the glut of ultra-luxury flats at the current rate).

Some would argue for them to be turned into council housing, as those protestors hoped for Centre Point in the Seventies. The most likely near-term option is that they’ll go on to the high-end rental market. Merilee Karr of high-end rental firm UnderTheDoormat.com says that “many developers don’t want to crystallise losses and cut prices, so we’re seeing developers rent out high-end properties to earn income while they wait for the market to return”.

Quite how long that will be is moot. As for Centre Point, it seems destined to remain a symbolic void – and perhaps emptiness is its business model.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments