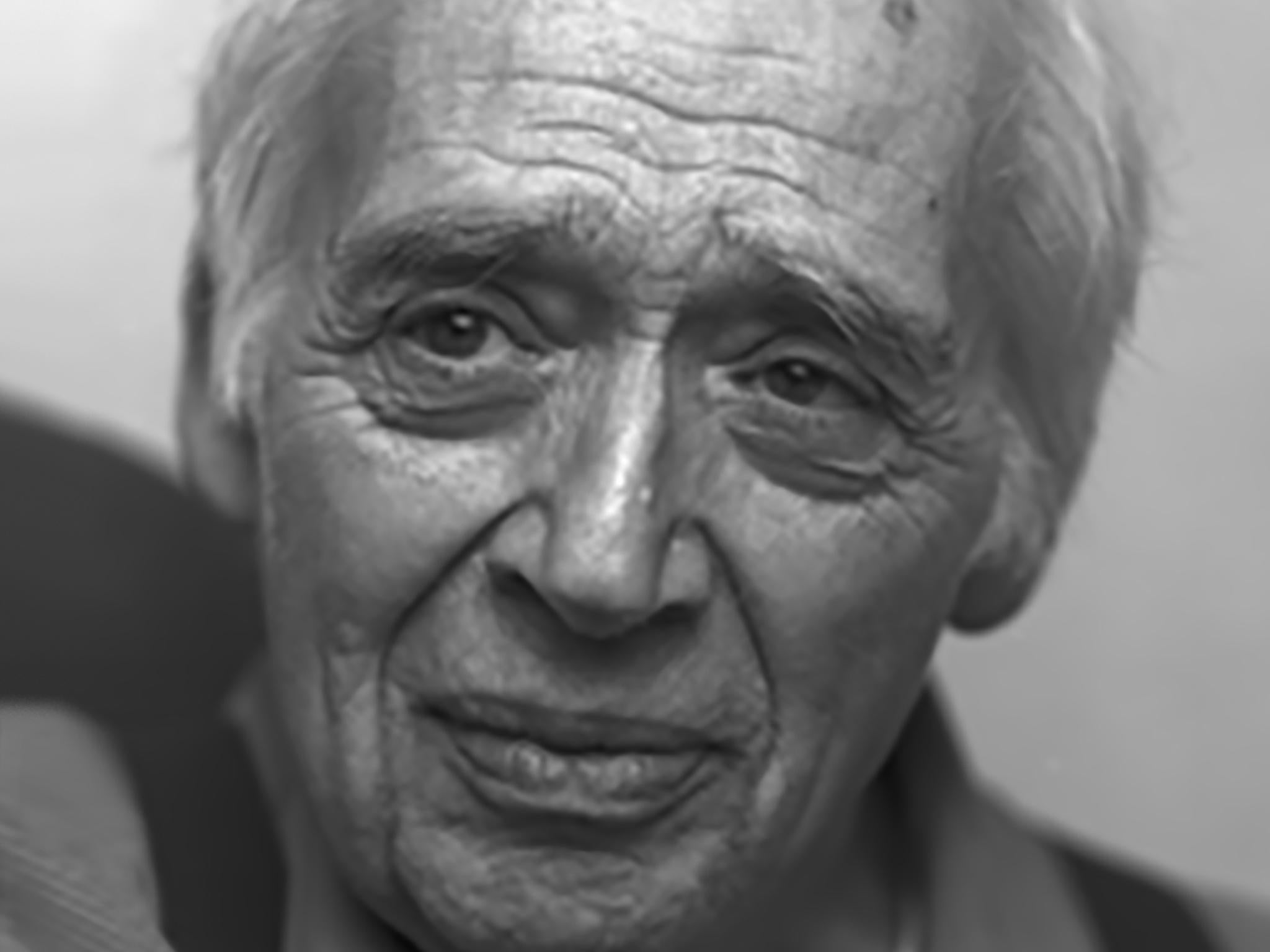

Harold Bloom: The literary critic who fell in love with Cleopatra

America’s venerable critic has just celebrated his 89th birthday and he’s still teaching, albeit by Skype. Andy Martin talks to him about his life and writing and discovers Bloom’s body might be failing but his mind is sharper than ever – and still treasuring the moment he fell in love with actress Janet Suzman

For a moment or two, I got to be Harold Bloom. “Andy, you understand about computers, don’t you?” says he. “Sit down in front of that computer and send an email for me.” Which is how I came to sign myself “Harold”. It was a message to a publisher asking him to send a copy of Bloom’s latest book, Possessed by Memory, a memoir mediated through literature, “to the magnificent British actress, Dame Janet Suzman”.

I’m visiting Harold Bloom, America’s venerable and semi-omniscient literary critic, at his beautiful old wooden house on a leafy street in New Haven, where – having just celebrated his 89th birthday – he is still teaching. Via Skype. He’s a bit too frail to be allowed on the Yale campus (they say the insurance won’t cover him).

“What was your high point then, looking back over your life?”

“Ah, Dame Janet,” he sighs.

After 40-odd years, he is still in love with Janet Suzman. His wife, Jeanne, is sitting right there by the way. She doesn’t mind. I should stress one thing (in fairness to all concerned): Bloom and Suzman have never met. Unless you count across a very crowded auditorium. She was playing Cleopatra at the National Theatre some time in the late 1970s. Harold Bloom was in the audience (as, by a strange coincidence, was I). For Harold, it was the coup de foudre. He was too shaken by the whole experience to ever articulate his passion, until a year or two back when I finally put the two of them in touch, over email.

“I know I will never meet her,” says he, forlornly. She will remain forever exactly as she was on stage, dressed as an Egyptian queen, her words precisely scripted by William Shakespeare. It is the purest love you can imagine, a literary love affair, based on highly metaphorical language. Cleopatra was in love with Anthony, but for at least that one evening Bloom was Anthony, even though he generally thinks of himself as more of a Falstaff, a hedonistic lover of life and adventurer.

Harold is not in great shape. He can’t go very far, physically speaking, except for regular trips to the hospital and a rehab clinic. He is wheelchair-bound. His wife says it’s all down to a weak heart and arthritis. He has a nurse attending him while I’m there. He calls out for ice to be put on his back. His hand is trembling as he signs a copy of his book. The last time he wrote to me, he said, with an apocalyptic air, “my future is indeterminate”. Which applies to us all, but especially to Harold.

His word for himself is “decrepit”. His mind is as sharp as ever it was, but inside a body that is in terminal decline. He is suffering from the opposite of dementia: decorporia, or physical disintegration. Mens sana in a corpore that is anything but sano. “There is a tremor in my fingers,” he writes, “my legs tend to give out, my teeth diminish, incipient macular degeneration dims my eyes, deafness increases, birdsong is scarcely heard, every height augments my apprehension of falling.” When he thinks about death, he quotes Dr Johnson: “This secret horrour of the last is inseparable from a thinking being whose life is limited, and to whom death is dreadful.”

There is a strange bond between us. My father’s name is also Harold. Middle name “Horatio”, which Bloom in his Shakespearean way is particularly fond of. “I’m old enough to be your father,” he says. I’m a bit of a prodigal symbolic son though. I struggle to remember the books my own father was particularly keen on. “He was more into motorbikes than books, to be honest,” I say.

I can do the things that Harold can no longer do: hiking up the mountains of Montana or surfing. “Don’t you ever get tired?” he says. In fact he hates going to the beach anyway: “I turn into a lobster when exposed to the sun.” He is content to keep on reading and keep on remembering.

There is an implicit and explicit shoutout in his work to Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, merging memory and art with an evanescent impression of immortality. His earliest memory is of playing on the floor of his mother’s kitchen while she prepared the Sabbath meal. As she goes by he reaches out and touches her toes; she reaches down and rumples his hair and says, “My sweet Harry”.

Now, approaching the end of his story, he likes to quote the Book of Ecclesiastes, chapter 12: “Also when they shall be afraid of that which is high, and fears shall be in the way, and the almond tree shall flourish, and the grasshopper shall be a burden, and desire shall fail: because man goeth to his long home, and the mourners go about the street.” A line in Ecclesiastes which I’ve never heard him quote is this one: “Much study is a weariness of the flesh.” He adheres to the later Jewish tradition (perhaps imported via neoplatonism) of study being the path to salvation.

He was born in 1930 in the Bronx, the son of immigrants, and grew up speaking Yiddish. “My father could speak Russian but refused to; my mother spoke Polish, but refused to, for political reasons.” He only learned English around the age of six when his older sisters brought it home from school. So he came at it from the outside, rather like Joseph Conrad or Vladimir Nabokov, and was (and remains) bewitched by the language.

His first reading was of the poets William Blake and Hart Crane, and he came to Shakespeare very early on, around the age of eight or nine he thinks. “When I was very young, I read poems incessantly because I was lonely and somehow must have believed they could become people for me.” Legend has it that he could read a thousand pages an hour (he says it was only 400 at best).

When I was very young, I read poems incessantly because I was lonely and somehow must have believed they could become people for me

He retains his youthful magical thinking about literature. Bloom has now written 40-something books about books – poetry, novels, plays, sacred texts. And his “memoir” is largely a homage to some of his favourite writers. As Oscar Wilde once said: “Criticism is the only civilised form of autobiography.” Bloom harks back to the Bible often enough, but he is (as he describes Marcel Proust) more of “an atheistic mystic”. He quotes Ralph Waldo Emerson with approval: “As men’s prayers are a disease of their will, so are their creeds a disease of the intellect.

Literature is the closest thing Harold has to a religion. Writers such as Shakespeare and Milton and Wordsworth are like a substitute for the elusive Yahweh of the book of Genesis. Which explains why he retains an essentially sacred view of writing and is concerned to defend the “western canon” (from Homer through to James Joyce) against unbelievers and sceptics (which probably includes me).

His attitude could be summed up in the opening lines of John’s Gospel: “In the beginning was the Word (logos), and the Word was with God (theon), and the Word was God.” But he was brought up on the Torah, the Jewish Bible, and was later seduced by the medieval tradition of Kabbalah, which says that the world was called into being via 10 utterances (or “Sefirot”) and that therefore the whole of life is language. Organised religion, monotheism-style, derived from a reverence for the written text.

Bloom derives consolation from the books that surround him on shelves and in piles on the table and on the floor. In Possessed by Memory, he writes that “Frequently at dawn, when I am very chilly and sit on the side of my bed, knowing it is not safe for me to go downstairs by myself in order to have some morning tea, I find deep peace in (Wallace) Stevens at his strongest.” If he was a Pharaoh, he would presumably ask to be buried with his books at his side.

He met his wife Jeanne in New Haven in 1955. They were both students at Yale. She was doing a degree in history, he had just returned from a year on a Fulbright scholarship at Pembroke College, Cambridge (England). They married in 1958. Now, more than 60 years later, she says: “You can’t stop him. Nothing would stop him from continuing to teach and write – it’s what he does.”

He tends to remember people according to the books or poems they make him think of. So for example, there was a student called Fergy he met at Cornell. She was from Kentucky. “She had freckles and red hair, and I always told her that she looked like a female Huck Finn. Tall, slim, incredibly graceful, she had a way of running around me as we walked, since she was swift and I was slow.” Everything is mediated through literature. “Almost every night I dream about departed friends, sometimes mixing them up with fictive characters.”

At this stage of the game – the dreaded “twilight” zone – Bloom has lost most of his old friends. His books are a way of calling them back again. The notion of a resurrection is still important to him – but one that precedes death. It is not surprising, when his own body is failing, if he finds consolation in images of transcendence, in which the soul is at last disembodied:

Hence in a season of calm weather

Though inland far we be

Our souls have sight of that immortal sea

Which brought us hither,

Can in a moment travel thither,

And see the children sport upon the shore,

And hear the mighty waters rolling evermore.

(Wordsworth, Intimations of Immortality).

He quotes from Proust’s account of the death of (his imaginary writer) Bergotte: “They buried him, but all through that night of mourning, in the lighted shop-windows, his books, arranged three by three, kept vigil like angels with outspread wings and seemed, for him who was no more, the symbol of his resurrection”.

There are perhaps three key concepts that recur again and again in Bloom: freedom, God, and immortality. All three of them appear as delusions, but ones that can be elusively attained or at least entertained in works of literature. Bloom would probably concur with Borges that literature is defined by “the sense of the imminence of a revelation that does not occur”.

None of which stops Bloom from forever searching, not just for his own earliest memories but what might be something like the earliest memories of humanity, for what he calls, “a primal sound, cast out of our cosmos and wandering in exile through the interstellar spaces”. One of the stories he is most drawn to in the Old Testament – the Book of Genesis – is that of Jacob, who finds himself wrestling with a passing god all through the night. Bloom sees that – a close encounter with the divine – as an allegory of his own life.

“In the half-light of my incessant nocturnal wakefulness, I begin to conceive of it as the struggle of every solitary deep reader to find in the highest literature what will suffice.”

Frequently at dawn, when I am very chilly and sit on the side of my bed, knowing it is not safe for me to go downstairs by myself in order to have some morning tea, I find deep peace in (Wallace) Stevens at his strongest

The “most important thing in the book” he says is his theory of “self-other seeing”, notably in Shakespeare, where characters like Hamlet and Macbeth are capable of seeing themselves from the outside, as if they were someone else – an idea to some extent inspired or inflected by the experience he has had when (more than once) falling and breaking some fragile part of his body: “I recall the repetition of an acute phantasmagoria that this was not happening to me but to some other person.”

One of his favourite words is agon, nothing to do with “agony” as such, but definitely concerned with struggle, as if in an arena (like Ben Hurr). He is certainly always struggling with something or someone, whether god or man, or just entropy in general.

My own theory is that, in the current context, his definition of a serious book would be anything that can’t be readily made into a movie or a video game (Joyce’s Finnegans Wake springs to mind.) Books are old school and contrive to hold new school technology at bay. “The final book here, The Book of Numbers, by the still-youthful Joshua Cohen, is a courageous assault on our Age of the Screen, the great grey ocean of the internet.”

I quote that from Bright Book of Life: Fifty-Two Novels to Reread ‘Ere I Vanish. While I was hanging out chez Bloom, as well as emailing Dame Janet, I also had to email myself the manuscripts of two other books that Harold has already written but not yet published.

One is Bright Book, the other is Take Arms Against a Sea of Troubles, a study of poetry, or “the power of the reader’s mind over a universe of death”. As his wife says, there is no stopping him. Each book is a way of deferring death, a bulwark against the erosion of time, a “symbol of his resurrection”.

In all writers and all times, in philosophers and poets, Bloom finds consolation – companionship – in the face of the void. But if you had to name one, it would have to be Shakespeare, and precariously poised as he is between being and non-being, it would have to be in the figure of Hamlet: “We defy augury. There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; it if be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows aught, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.”

Andy Martin is the author of With Child: Lee Child and the Readers of Jack Reacher (Polity) and teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments