Karl Marx 200th anniversary: The world is finally ready for Marxism as capitalism reaches the tipping point

The philosopher predicted that centralisation would lead to revolution and give birth to a post-capitalist society – globalisation has led us to that point

Two hundred years ago on 5 May 1818, Karl Marx was born in the German town of Trier on the banks of the river Moselle. Serendipitously, at the start of this bicentennial year, I found myself invited to a wedding in what used to be called Karl-Marx-Stadt, since renamed Chemnitz, in the former East Germany. Communism may have formally collapsed with the downfall of the Soviet Union, yet it has not been extinguished.

The world’s most populous state and rising superpower, China, is officially communist, albeit nominally. And socialist ideas remain prevalent throughout the world. The resurgence of socialism could be seen in the Chavismo new left wave of Latin American politics (admittedly now in the process of being rolled back). In the US, self-proclaimed socialist senator Bernie Sanders could well have been as unlikely an occupant of the Oval office as Donald Trump – if the Democratic National Committee had not conspired against him.

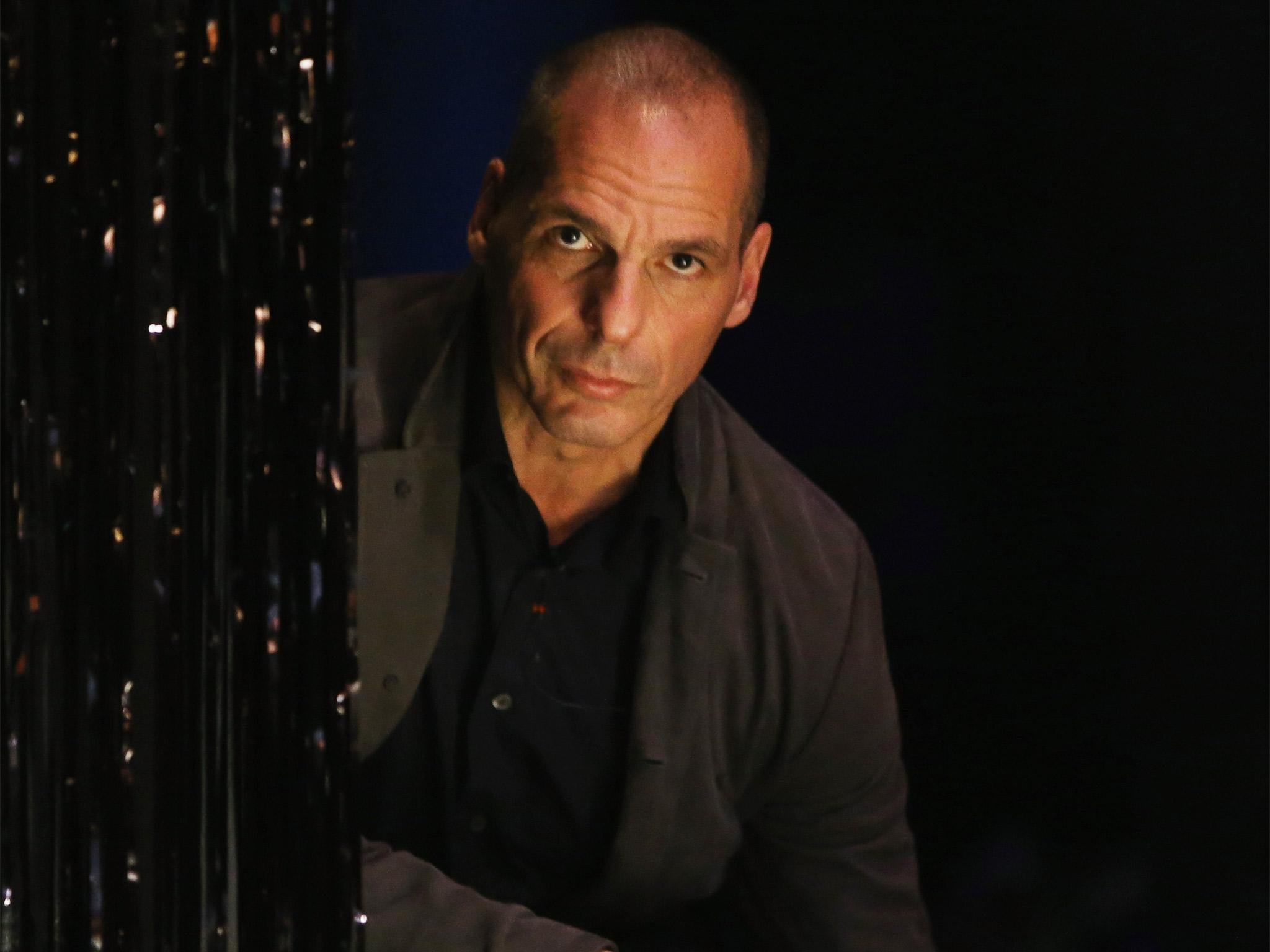

In the UK, unapologetic socialist Jeremy Corbyn swept to the leadership of Her Majesty’s opposition, appointed Trotskyist John McDonnell as shadow chancellor (McDonnell recently told the Financial Times that their aims for Britain are socialist), pronounced socialism as no longer a dirty word to a delirious conference, before garnering 40 per cent of the vote in the general election. In France, Jean Luc Mélenchon performed respectably in the first round of the French elections, commanding nearly 20 per cent of the vote. In Greece, the left-wing Syriza government remains in power – even though its manifesto has been crushed by international finance capital. Its former finance minister and firebrand Yanis Varoufakis describes himself as a lapsed Marxist. His recent essay penned in The Guardian cites Marx’s analysis as both the key to understanding our present predicament and the way out of it.

Millennial capitalism

In 2015, socialism was the most searched word on Merriam Webster’s online dictionary. Socialism does not carry historical baggage for a younger generation left behind by the iniquities of capitalism. A Harvard study found that a majority of millennials reject capitalism and a third are in favour of socialism. This is what might be called the revenge of Marx; the rehabilitation of one of the world’s historical philosophers. Marx inverted Hegelian doctrine into dialectical materialism, affirming that it was material relations that were responsible for consciousness and social relations – not the other way round. In 2011, back when it was still unfashionable to confess to being Marxist, Oxford University literary theorist Professor Terry Eagleton boldly decreed that the bearded prophet had been right after all. Eagleton is no longer alone.

A slew of books herald the end of capitalism, in the words of economic sociologist Wolfgang Streeck, and announce that we are entering the epoch of Postcapitalism, according to the gospel of journalist and author Paul Mason. The most dangerous philosopher in the West, Slavoj Zizek, according to The New Republic magazine , is communist; one of his recent tomes, Living in the End Times, conjures up the apocalyptic sense of the death throes of capitalism.

Of course, it wasn’t meant to be like this. Marx’s ideas had apparently been discredited with the collapse of communism and consigned to Trotsky’s dustbin of history. Hadn’t history proven that communism was not a historical inevitability? Then came the 2008 financial crash and the demise of political economist Francis Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’. A decade of austerity was the death knell for the ideological vacuum. The fall-out has seen a polarisation between authoritarian nationalism and progressivism; between dystopia and NOT dystopia, if you like.

Neoliberalism always presented itself as depoliticised, in that the free market is akin to an all-enveloping atmosphere and as irresistible as a force of nature. Its allocation of resources and outcomes supposedly only required mere supervision through technocratic managerialism. In reality, it could not have been more ideological, operating through the corporate capture of the state and hollowing out of the institutions of civic society. Global capitalism appeared to be indomitable and impregnable, in so far as it was the hegemonic system. Yet at the same time, the delayed reaction of a series of political earthquakes, in the form of the Arab Spring and a wave of authoritarian populism, has exposed its vulnerabilities. Even if these events have not challenged the fundamental basis of the system, its neoliberal globalisation variant is under attack.

Mao Zedong’s description of capitalism as a paper tiger seems as pertinent as ever. Marxism bequeathed a rich legacy of thinkers, ranging from Lenin and Trotsky to the Frankfurt school, as well as the likes of Antonio Gramsci, Fredric Jameson and Alain Badiou. It was once unthinkable to break with Marxist orthodoxy on the left. Until, as American Marxist Marshall Berman relates in his modern classic All that is Solid Melts into Air (taking its cue from the famous phrase in the Communist Manifesto), a group of disaffected French post-structuralists and postmodernists, namely Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes, did just that. Disillusioned by the defeat of May 1968, when an uprising against De Gaulle resulted in his party emerging even stronger than before, they broke ranks.

In the intervening decades, the battles of identity politics have been significant but they have also been hampered by the lack of a structural, systemic understanding of how capitalism operates. Where resistance has mirrored the fragmented, atomised, hyper-individualism of neoliberalism then it has often been doomed to failure. All of which is very much bound up with the Cold War victory of the US empire. The CIA saw its chance, according to a recently declassified research paper. The agency read French postmodern theory, concluding that its questioning of the objective basis of reality could be used to undermine the Marxist doctrine of historical and teleological inevitability. Millions of dollars were pumped into front organisations such as magazines, publishing houses and favoured academics, in order to push postmodern ideas and to create a centre left, thus demarcating the outer boundary of respectable ideas – anything beyond which could be denounced as dangerous and radical lunacy. After all, the strategy of divide and rule has generally been the preferred one of the ruling class.

The ruling class

Marx was familiar with the methods of the ruling class. He was often on the run from European authorities, eventually finding refuge in the relative tolerance of London where he divided up his time between his smoke-filled home (Soho then later Kentish town), the British Library and watering holes. His rebellious life – immersed in the struggles of the 19th century, from the 1848 revolutions to the Paris commune – lent itself, naturally, to the counterculture of the late 20th century. And now to the glamour of the big screen. A new Marx biopic – The Young Karl Marx from I Am Not Your Negro director Raoul Peck – has been released. Marx’s starting point, outlined in his 1844 letter For A Ruthless Criticism of Everything Existing to fellow philosopher Arnold Ruge, is a philosophical tabula rasa comparable to a Cartesian wiping of the slate clean. This position of ‘Kritik’, adopted by the young Hegelians, gradually evolved into praxis for Marx. Hence, in Theses on Feuerbach (1888), Marx states “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it”.

The Communist Manifesto itself was not merely a political and economic tract. It is a call to arms, as well as a work of canonical sublimity and literary fecundity; by turns poetic, inspired and visionary. Author and journalist Francis Wheen’s biography describes the Damascene moment at which Marx anoints the word ‘proletariat’. It descends on to the page like a thunderclap across the landscape, presaging the revolutions to come of the 20th century. In the wide-ranging debate Die Judenfrage, or The Jewish Question, Marx posits that the liberal definition of freedom is limited. The motto of ‘Liberté, Egalité, Fratérnité’ of the French revolution is just that – a good slogan. To take one example, equality does not relate to power or wealth but merely denotes equality before the law.

Marx formulates that consciousness is generated by the mode of production, in a classic inversion of the Hegelian system. He defined alienation as the quintessential state of mind and being under capitalism, corresponding to the economic relations of commodification, exploitation and oppression. It is a state of mind that is little understood by the billions who experience it daily. Thus, bourgeois society is predicated on economic individualism, private ownership and self-interest. The relations between individuals, including intimate relations, are thus egoistical. Pure self-interest becomes the prime driver of not just economic processes but all relations. Under capitalism, every entity, no matter how sacred, can be transformed, exploited and sold for profit. This is what Marx meant by the intrinsic process of commodification. And it is this limitless commodification which extends into every sphere, including sex, the body and relationships.

Online pornography, social media and dating apps are merely the latest extrapolations of this relentless commodification. Furthermore, social roles and relations are engendered by historical modes of production. Thus, the agrarian, feudal world corresponds to the social strata of monarchy; aristocracy and the church dominating and exploiting the peasantry. Similarly, the industrial, urbanised world corresponds to the social structure of the bourgeoisie exploiting the proletariat. In a memorably thunderous passage in The Communist Manifesto, Marx extrapolates this connection between social and economic relations to define free trade: “It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom – Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.”

Marx outlined the history of mankind as the history of class struggle in which the classes are opposed in a dialectical paradigm. Thus, we move from antiquity with the duality of slave owner and slaves to the feudal age of lord and serf to the capitalist age of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. It is these same unsustainable contradictions that Marx later proposes will bury capitalism, when the burgeoning proletariat become the ‘gravediggers’ of the bourgeoisie. This ‘final’ stage will usher in communism, completely transforming and reconfiguring the previous relations into a classless society. Marx outlines that communism, in abolishing private property, also abolishes alienation and wage bondage, leading to worker emancipation and, by extension, universal emancipation. Nevertheless, Marx subscribes to the enlightenment belief in the rationality and logic of mankind to create a narrative of progress. The bourgeois capitalist system is perceived as a necessary step in this progression, enabling the transition from a feudal, agrarian society into an urban, industrialised one. Thus, the bourgeoisie is portrayed as having played a revolutionary role in transforming the world. In its propensity for upheaval and turmoil, capitalism never ceases to alter the world.

The dialectical materialist analysis of the history of class struggle played out in the contradictions of Marx’s own life. Whether in his marriage to the aristocratic Jenny Von Westphalen, or his friendship with industrialist Friedrich Engels, which enabled the genius of Marx and offset the penury of his journalism and political activities. Some of the most switched-on uber capitalists and masters of the universe concede that Marx’s basic analysis of capitalism has never been improved upon. Trump billionaire backer and donor Peter Thiel states that the breakdown of the status quo points either towards libertarianism or Marxism. Billionaire investor Warren Buffett infamously once said: “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.”

Concentration of wealth

The Marxist critique of capitalism hinges on its innate tendency towards concentration and centralisation of wealth. In Capital Volume 1, Marx fleshes out the M-C-M circuit (in which M is money and C is commodities). This circuit guarantees the expansion of capital, providing the economic basis of capitalism as a mechanism for limitless capital accumulation. The resulting crises of overproduction and capital accumulation are resolved through the enforced destruction of productive forces, the conquest of new markets and more thorough exploitation paving the way for more extensive and destructive crises. Fracking might be viewed as the ultimate metaphor for this process, whilst Uber is emblematic of the same hyper-exploitation.

French economist Thomas Piketty’s work, updating the original title to Capital in the Twenty-First Century, using a large amount of historical data, has further corroborated Marx’s theories on the concentration of wealth. Unsurprisingly, several decades of neoliberalism have been the greatest testament to how a deregulated capitalism, red in tooth and claw, siphons wealth to the top 1 per cent or even 0.1 per cent. Recent figures show that the wealthiest eight billionaires in the world (whom you could fit into a people carrier) have as much wealth as the bottom half of the global population, or some 3. 5 billion people. Astonishingly, the equivalent figure was the 62 wealthiest billionaires in 2016. Back in 2010 it was more than 300. This is how rapidly wealth is being sucked up to the top – this may be termed the vacuum-up effect as opposed to the myth of trickle-down economics.

Whilst Victorian capitalism was dominated by small-to-medium-sized companies, the middle decades of the 20th century witnessed a shift to statist capitalism. In effect, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China represented variations on this theme. Since then the age of globalisation has been ushered in with multinational corporations straddling the globe – many of them larger than the states they operate in. The movement of vast pools of capital on a global scale is historically unmatched. Mega mergers seem to be rarely out of the headlines. In other words, the centralisation Marx predicted 150 years ago is panning out.

There is a one-way trend towards the control of capital by an ever smaller number of players. Neoliberal doctrine emphasises the virtues of competition. Yet the reality of deregulated free markets, most evidently in financial services, has been monopoly, cartels, collusion and rigging. This is evidenced by the big four dominance in every sector from banking, accountancy, magic circle law firms, to high street supermarkets, energy companies and privatised utilities. The contradictions of the system have now attained a new level of absurdity.

Capitalists presently invest in existing money, be it financial instruments, housing or debt, in order to make profit. In fact, this financialisation of the economy has superseded the traditional profit-making processes of manufacturing. Unlike manufacturing, this financialisation does not create value. Instead it creates asset bubbles of financial and housing speculation, which eventually burst, as happened on a seismic scale in the 2008 crash. Since the 1970s there have been a series of escalating market crises – yet even this volatility is profitable for hedge funds.

So if late capitalism is economically, socially and ecologically unsustainable, not to mention bankrupt, then whither to from here? One of the obtuse criticisms of Marx has been the lack of a blueprint, despite the fact that a participatory, truly democratic society would need to emerge organically rather than following a roadmap. Marx posited revolution as “the driving force of history”. The overthrow of the existing state and the dissolution of property would lead to liberation extending to the dissolution of the bourgeois conceptions of family, marriage and all nation states. This liberation from national barriers would then bring everyone into connection with the production of the whole world for the pleasure of their consumption.

Under communism, Marx daintily describes how one would be able to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening and criticise after dinner (naturally). Communism would appear to truly represent the end of the history, or at least the end of history, as class struggle : “Communism is the riddle of history solved and it knows itself to be this solution.” Marx formulates that human emancipation can only be achieved by going beyond the bourgeois framework; material emancipation translates into spiritual and sensuous emancipation. Only the resolution of the material modes of production, beyond the paradigm of economic individualism, private property and self-interest, can liberate consciousness and revolutionise social relations – such that there is the capacity, the capability and propensity for free behaviour and genuine ties between individuals based on love, warmth and affection, rather than purely calculating and cold self-interest.

Alternative future

The exultant victory lap of all-singing, all-dancing capitalism has been remarkably brief; the unipolar moment of American triumphalism short-lived. Only recently, US defence secretary Jim Mattis announced that the era of great power politics has returned. Undoubtedly, a set of progressive ideas is coalescing amongst the new left – a green economy, public and democratic control of the economy, full automation. This 21st century manifesto is embodied in such books as Inventing the Future. The critical question remains of the vehicle necessary to bring about this transition.

There is no doubt that 21st-century global capitalism is far more sophisticated and resilient than that of pre-revolutionary Tsarist Russia. The transition of capitalism to an alternative political and economic system will likely play out over a protracted period, even if it is catalysed by revolution. Much in the same way that feudalism evolved into capitalism through the dual industrial (economic) and French revolutions (political), in which the bourgeoisie superseded the aristocratic order preceded by the 17th-century English civil war.

Or to leave the last word to Marx: “No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society.”

Youssef El-Gingihy is the author of ‘How to Dismantle the NHS in 10 Easy Steps’, published by Zero books

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments