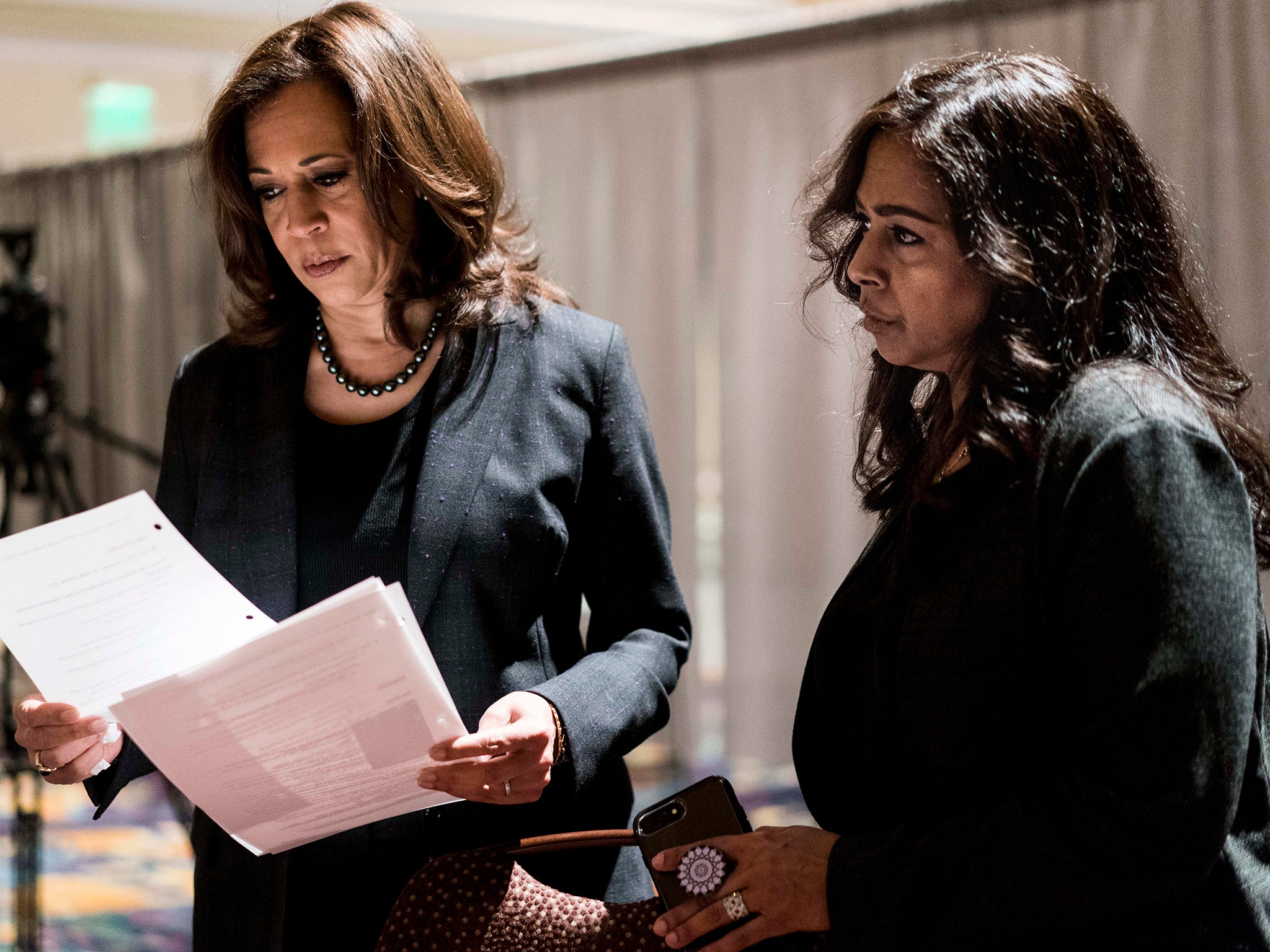

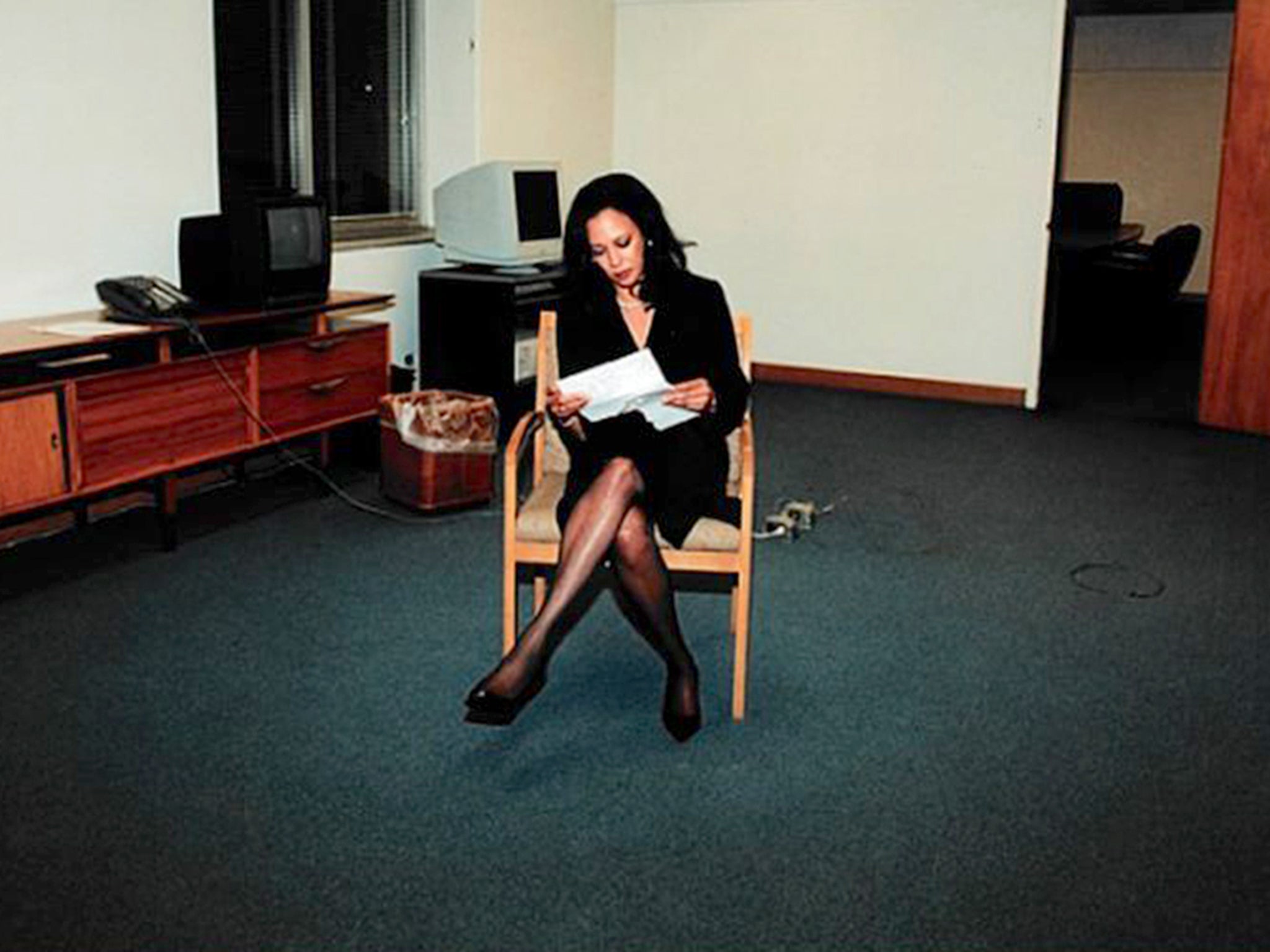

Kamala Harris: Presidential hopeful and big sister – but who is the woman behind the politics?

United States senator Kamala Harris is known for fearlessly advocating what she believes in. But who is the real Kamala? Her little sister Maya can tell you, writes Ben Terris

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the Fourth of July, Independence Day, and Kamala Harris was explaining to her sister, Maya, that campaigns are like prisons.

She was recounting how in the days before the Democratic debate in Miami, life had actually slowed down to a manageable pace.

Kamala, Maya and the team had spent three days prepping for that contest in a beach-facing hotel suite, where they closed the curtains to blot out the fun.

But for all the hours of studying policy and practising the zingers that would supercharge her candidacy, the trip allowed for a break in an otherwise all-encompassing schedule.

“I actually got sleep,” Kamala says, sitting in a Hilton conference room in Des Moines, smiling as she recalls walks on the beach with her husband and that one morning SoulCycle class she was able to take.

“It’s a treat that a prisoner gets when they ask for, ‘A morsel of food please’,” Kamala says, shoving her hands forward as if clutching a metal plate, her voice now trembling like an old British man locked in a Dickensian jail cell. “And water! I just want wahtahhh... Your standards really go out the f***ing window.”

Kamala bursts into laughter.

****

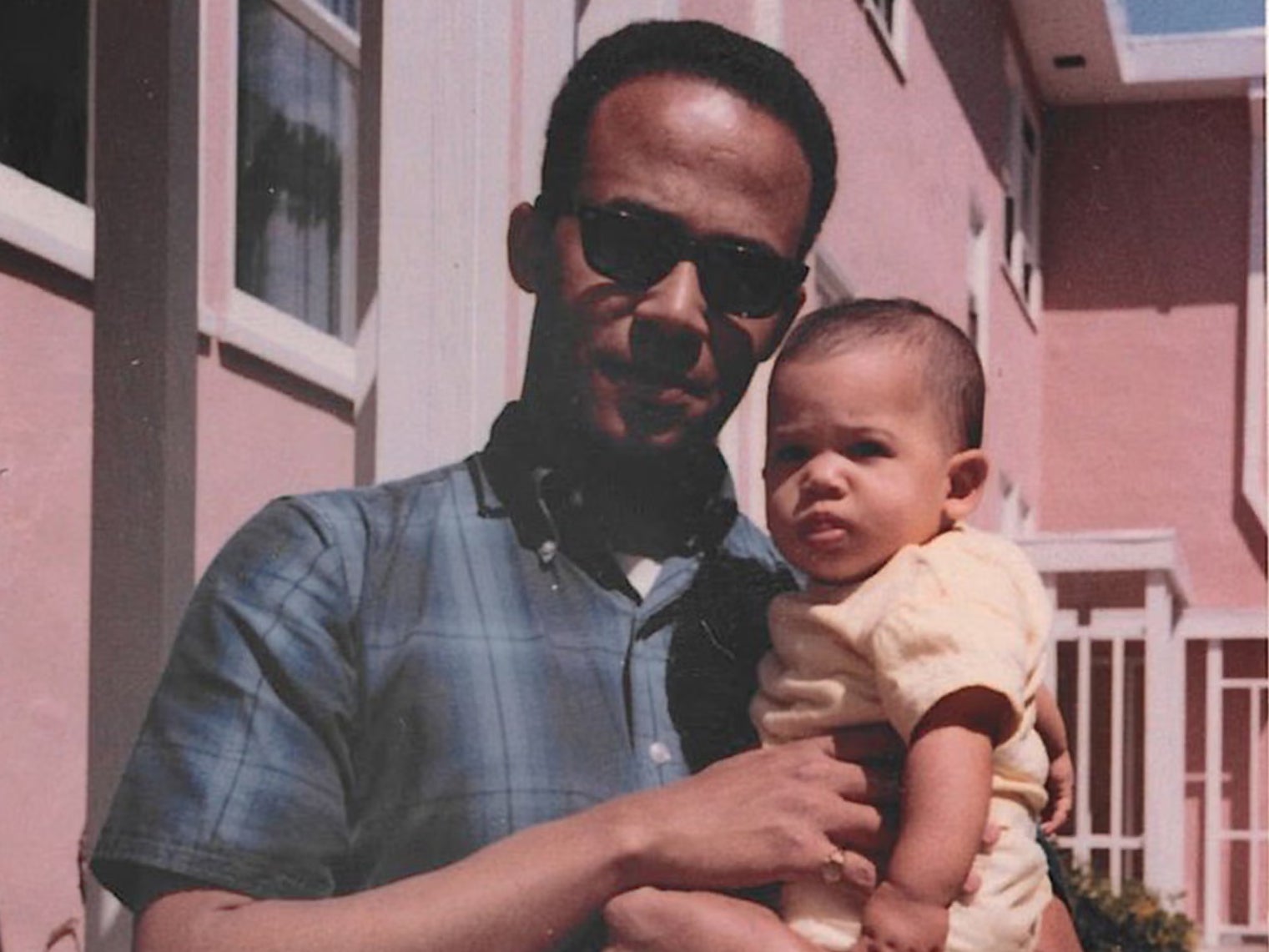

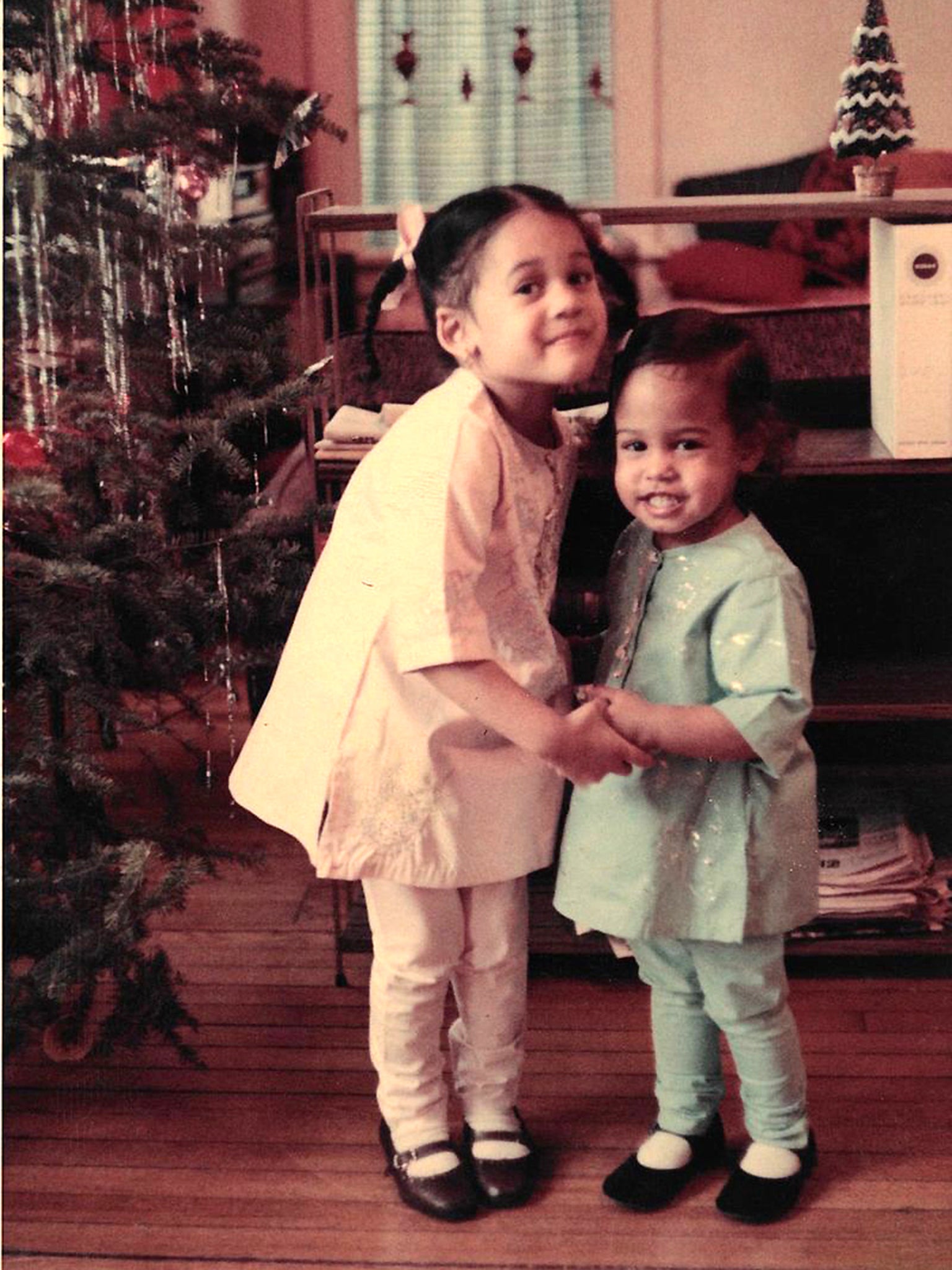

The Harris sisters don’t look all that much alike. Kamala resembles their father, taller and angular; where Maya has the softer features of their late mother who clocked in at 5ft 1in. But the sisters share a contagious, bodyshaking laugh so similar that strangers often guess they’re related.

Maya has always got Kamala’s best interests at heart, whether it’s ignoring the former prosecutor’s joke comparing a campaign to incarceration, making sure she’s fully up to speed on policy, or getting enough rest – and not just because she’s the little sister, but because she’s Kamala’s campaign chairperson.

It’s a job Maya’s uniquely qualified for: she was a senior adviser for Hillary Clinton in 2016, knows her sister better than anyone else, and is something of a yin to Kamala’s yang.

Where Kamala, California’s former attorney general, came up through politics as a law enforcement official – a job that has become controversial among liberal Democrats – Maya has been at the forefront of criminal justice restructuring: as a leader at the American Civil Liberties Union, as a vice president at the Ford Foundation, helping edit her friend Michelle Alexander’s seminal book about mass incarceration, The New Jim Crow.

Maya is, in other words, exactly the type of person who might criticise Kamala’s campaign from the sidelines.

“If people knew who Kamala was, and what she believes and where her heart is,” Maya says, “I think it would be hard not to reach the conclusion that this is the person who would be the most passionate advocate for the things we’ve been fighting for for a long time.”

Over the course of Kamala’s political career, she has been many things: tough on crime, progressive, pragmatic, hard to fit into an ideological box. Sometimes during this campaign it can seem as if she’s trying to please all the people all the time, and sometimes it’s like she just can’t please anyone.

Questions of who she is, what sits at her core, and why exactly she wants to be president have become central to her campaign and chances of winning. Maya doesn’t have these concerns about Kamala. Her trick then, in her own words, is this: “How do you bridge the gap between what you know about someone, and what people think about someone?”

****

On a recent swing through South Carolina, Kamala spoke to an audience of overheated, mostly black voters who had packed into a gymnasium in Columbia to feel her out.

How do you bridge the gap between what you know about someone, and what people think about someone?

“I was raised that you don’t talk about yourself,” Kamala says. “But I’ve also realised that in order to form relationships it’s important to let people know about my people.”

It’s the kind of thing a faux-humble person might say when running for president: even the book she wrote to launch her campaign revealed little about her inner terrain.

Her inability to get personal had been so much of a problem in the early months of her campaign that at one point, with her poll numbers treading water, she felt the need to apologise.

“I’ve been trying to get her to tell more stories,” Maya says, and Kamala did just that.

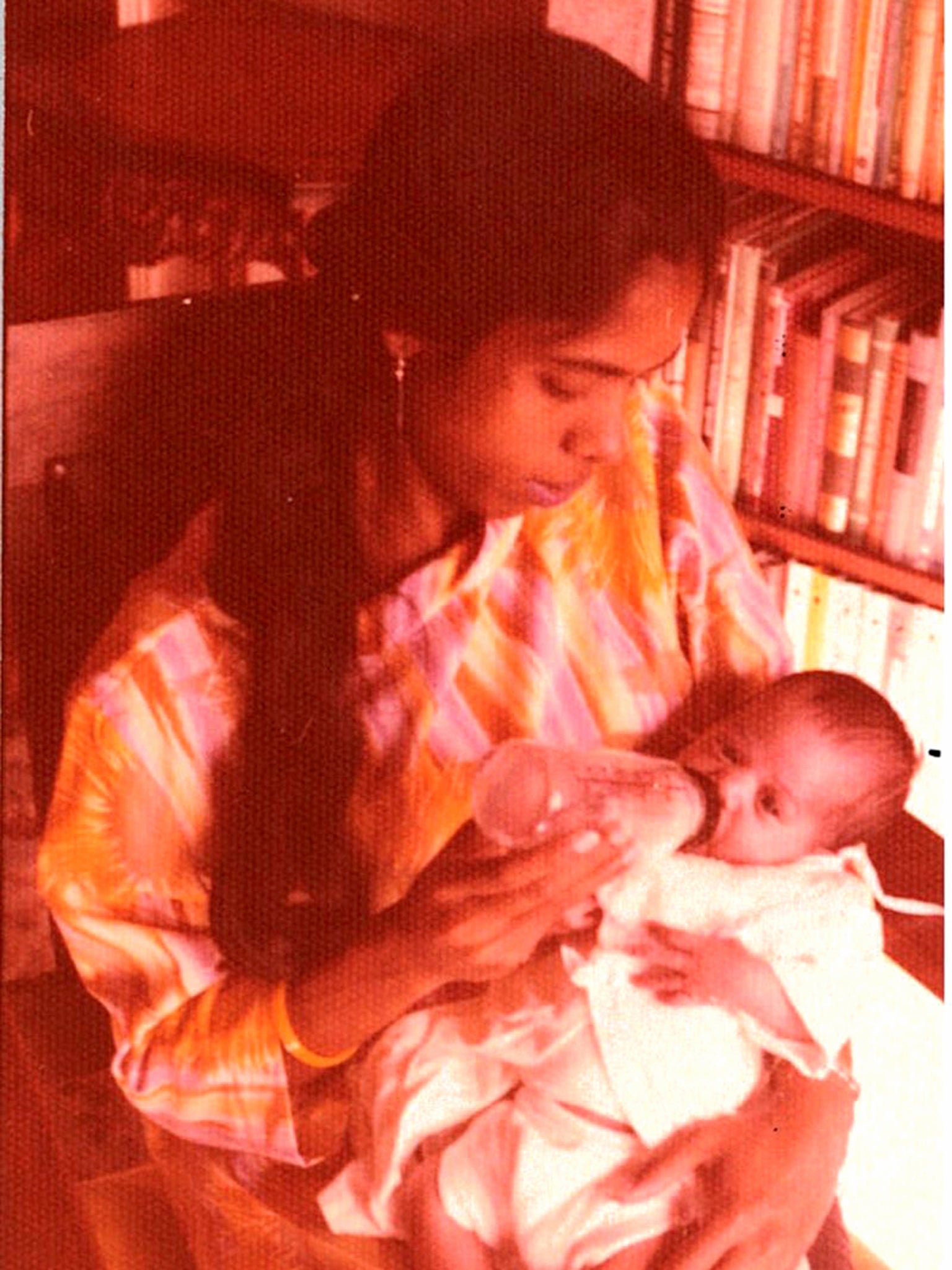

Their father, Donald, was a Stanford economics professor from Jamaica, and their mother, Shyamala, was a scientist from India, but before that they were a couple of civil rights activists attending the University of California at Berkeley.

“We joke that we grew up surrounded by a bunch of adults who spent all their time marching and shouting about a thing called justice,” Kamala said at the Columbia gathering, getting laughs from the crowd with a story about going missing from her stroller at a protest.

Shyamala and Donald split when the sisters were young, after which it was mostly just “Shyamala and the girls”, and sometimes, when Shyamala had to travel for work, it was just the girls. (Shyamala died in 2009, and Donald has what friends of the family call a “strained” relationship with his daughters.)

When feasible, Kamala and Maya would tag along to their mother’s conferences, getting the run of the place in hotels around the world. Other times, Shyamala would travel without them, leaving the girls under the care of neighbours they considered family.

But no matter who was looking after them, Kamala was looking after her sister, and that often meant using her fists in the schoolyard.

I was raised that you don’t talk about yourself. But I’ve also realised that in order to form the relationships, it’s important to let people know about my people

“Kamala was very feisty, and always fighting,” her friend since childhood, Peter Monroe, explains. “She was always either going to be putting people in prison or going to prison.”

Kamala remembers the skirmishes: “It was the Seventies! People fought on the schoolyard. This was before timeouts.” But she also remembers the fun: playing Miss Mary Mack on the yellow bus that took her 30 minutes to get out to Thousand Oaks Elementary, leaving her diverse, middle-class neighbourhood to help integrate a school that a decade earlier was only 2.5 per cent black.

It’s obvious now that Maya was right to push Kamala to share more of her personal history. Less than a month after speaking in South Carolina, Kamala’s campaign surged in the polls, all because she took to the debate stage in Miami, and had gone after former vice president Joe Biden by telling her story. Months earlier, Kamala and Maya had been “surprised” to learn about Biden’s past opposition to busing initiatives to integrate schools in the 1970s. To them, it felt personal. Onstage, Kamala told the story of one child who benefited. “That little girl was me,” she said.

****

Some stories, however, are too complicated for a stump speech.

When the girls were 12 and 9, Shyamala accepted a job at McGill University, moved the family out to Montreal, and enrolled Kamala and Maya in a neighbourhood school where everyone spoke French except for them. They remember the Mayflower truck coming to bring all their belongings across the continent, they remember arriving at their apartment and hiding from the cold in the closet, and they remember how their relationship further solidified in a place where no one else spoke their language.

“We leaned on each other,” Kamala says. “We forged a bond that is unbreakable. When I think about it, all of the joyous moments in our lives, all of the challenging moments, all of the moments of transition, we have always been together.”

Almost always, anyway.

Kamala graduated from high school and went to Howard University in Washington DC. She immersed herself in the campus political scene, running for student government, protesting apartheid outside of the South African embassy with fellow students. Big things were happening in the world, and Kamala wanted to be a part of it.

With Kamala at Howard, Maya moved back to the Bay Area. Her mother technically moved back too but still had work in Montreal, which meant at times Maya lived alone among their community of honorary aunts, uncles and cousins. “If the alarm went off at the house, she’d call me,” says Monroe, who lived nearby. “Her mother instructed me to keep the boys from chasing after Maya.”

Maya’s transition was easy enough. She was pretty (the best looking, according to her graduating yearbook), getting stellar grades and popular. And so no one seemed to notice anything was up as she made her way through senior year wearing bigger and chunkier sweatshirts (it was, after all, the 1980s).

“Nobody knew she was pregnant until she was about eight or nine months,” recalls Judy Robinson, a close friend whose mother used to take care of the Harris sisters when Shyamala was away. Maya graduated from high school at 17 years old with honours, in her second trimester, and kept a secret that even her closest friends didn’t know about.

“I remember Shyamala saying she cried for about four days,” Robinson says. “She cried for the fact that she was not there, that Maya went through this on her own without her.”

Maya does not talk about this part of her life. Not the pregnancy. Not who the father was (other than to say he was never really in the picture). Not who she kept the secret from or for how long.

She will talk about what came next: the birth of her daughter, Meena; her mother helping babysit while she finished college on time; the handsome law school friend and future husband, Tony West, who would help look after Meena at Stanford; the fact that her daughter and sister always had a “special relationship”.

“For me,” she says when asked about what it was like to be pregnant at 17, “it’s always about pushing forward, never really looking back.”

We forged a bond that is unbreakable. When I think about it, all of the joyous moments in our lives, all of the challenging moments, all of the moments of transition, we have always been together

In that way, she’s a lot like Kamala.

****

“Given all my lefty friends, it still amazes me that this ACLU lawyer ended up with a sister – and a husband – who both became prosecutors,” Maya said, speaking at her sister’s inauguration as San Francisco’s district attorney in 2004.

Maya had worked on that campaign, and been at her sister’s side on election night. In her speech, Maya joked about the possibility of awkward Thanksgiving dinners with “the ACLU lawyer on one end of the table and the district attorney at the other”.

There was some truth to the joke. “Kamala would make her argument very persuasively and forcefully and turn to me and say, ‘Brother-in-law, you were a prosecutor, you agree with what I say’,” West says. “And no less forcefully, Maya would say, ‘Honey, you know I’m right, right?’.”

In Maya’s line of work, prosecutors were often seen as the opposition. They were gatekeepers of an unjust system that locked up people of colour in disproportionate numbers, lawyers who often cared more about their conviction rate than actual justice.

But just as Maya had encouraged the ACLU to adopt more political strategies when she’d arrived in 2003 – bringing in pollsters and arguing that making progress on issues such as gay rights, voting enfranchisement for felons and juvenile justice restructuring required a campaign mentality – she argued that it was better to have people with her values inside the system.

In many ways during her time as district attorney and later as attorney general, Kamala proved Maya’s point. She declined to seek the death penalty against a gang member who had killed a police officer, she worked on re-entry programmes for ex-offenders and she fought to loosen a draconian “three-strikes” law.

But before Kamala had even announced her candidacy, she was hip-checked from the left, in the form of a damning op-ed in The New York Times by Lara Bazelon, a law professor at the University of San Francisco, with the headline: “Kamala Harris was not a ‘progressive prosecutor’.”

For all the ways Kamala worked to shake up the system, she did plenty to uphold the status quo. Bazelon said in an interview that Kamala was “misrepresenting her record” by “latching on to a trendy label” when she had actually supported high cash bail costs that made it difficult for poor people to stay out of jail before trial; opposed a death row inmate’s request for advanced DNA testing to prove his innocence (she later told the New York Times she regretted that decision); laughed at a political opponent’s support for the legalisation of marijuana; promised voters during her attorney general campaign that she would enforce capital punishment; and followed through, appealing a judge’s ruling that deemed the death penalty unconstitutional.

The challenge, Kamala says, is that people don’t always know the “spirit with which” many of her actions were taken. “People don’t know me,” Kamala adds.

But even some of the people who do view her actions within a political context see it as a way to move up within a system. “I think she had this perspective of: what’s my next step up the ladder?” says Aubrey Labrie, a longtime family friend. “I think that’s what’s ultimately driving her.”

Kamala would make her argument very persuasively and forcefully and turn to me and say, ‘Brother-in-law, you were a prosecutor, you agree with what I say’

For the sisters to have an inside and outside game, Kamala needed a seat at the table. And even though Kamala wasn’t exactly a hardliner, she was running for office in a different context back then.

In an ad she ran during her attorney general run, one that has mostly disappeared from the internet, Kamala brags that she “started prosecuting parents who let their children skip school”.

Now, the calculus is different. Democrats are coming around to positions on criminal justice restructuring that Maya has held for decades. Today, Maya can help the campaign by giving voice to the policies she knows so well, and act as a conduit to the activist base of the party that might otherwise be hard for Kamala to reach. But what about then? What did Maya think about, say, Kamala’s truancy initiatives at the time?

“If I had to speak for Maya,” Kamala says, answering the question. “It was well known, among people who knew me, that I never had any intention of criminalising parents.”

Maya nods along. “In talking with you about issues, I never questioned your motives,” Maya says, turning to Kamala to speak broadly about her tenure. “I know what your values are. We may have to agree to disagree about the way to go about it.”

****

Finding people to trust in politics – a field full of mercenaries with their own interests at heart – can be a tough thing to do. It’s no wonder so many people turn to family members: John Kennedy had Bobby, Joe Biden’s sister once ran his campaigns, and Ivanka Trump remains one of the president’s most visible advisers.

But Kamala’s campaign is even more of a family affair than others. Some of Kamala’s former staffers say this is because she can have trust issues, that unless you’re in the inner circle, connecting with the boss is next to impossible. Kamala has certainly been under a microscope more than your average politician: there just aren’t that many women or people of colour who become district attorney, let alone attorney general.

“In campaigns there will be those people who are part of your safe group,” Kamala says, wrapping up the interview. “The group of people you could call at midnight could laugh at the thing you’re not supposed to laugh about, cry, scream, curse and not be judged.”

And Maya does not judge her sister. In Maya’s mind, there have always been “prosecutors”, and then her “sister the prosecutor”: the first being a group she views sceptically, the latter being the one she trusts. She thinks it has made her a better advocate to know a little bit about the other side’s thinking, and believes she can help Kamala become a better politician by opening doors to the more progressive wings of the party. She can be, in the words of Zerlina Maxwell, who worked with Maya on the Clinton campaign, a “co-sign” on her sister’s candidacy.

“To have Maya in that small circle where I can have many conversations with very few words and with someone who completely understands my perspective because she’s lived it,” Kamala says, “it can be very validating.”

****

Before a town hall in Greenville, South Carolina, Kamala and her sister met with a small clutch of local officials, activists and supporters for some meeting and greeting in a backroom adorned with American flags. Many of the people had never met Kamala before, but had talked to Maya more than once on the phone.

“I say, ‘I would love actual feedback’, and they’re candid,” Maya says, after posing for a selfie. “It can be easier to tell me than to tell her. And I can tell Kamala. Like it or not, I’ve been doing that forever.”

Maya quit her job as an MSNBC analyst to volunteer for her sister. (“She’s invaluable,” Kamala says. “There’s no amount of money I can pay her, so I pay her no amount of money.”) Maya’s husband, West, now the general counsel for Uber, has helped Kamala prep for a possible contest with Trump. (In one mock debate, West played the role of the president, and even came up with a Trumpian nickname for his sister-in-law that he won’t repeat publicly.) And Kamala’s husband, Doug Emhoff, is a regular presence on the trail, serving as her biggest fan (“I see a president up there,“ he said, beaming after a speech in California), and enforcer from the sidelines (“F*** you, do better, don’t be so lame,” he grumbled about Biden, in the midst of his wife’s feud about busing with the former VP).

Kamala met Emhoff, a lawyer with two children from a previous marriage, on a blind date in 2013 and married him a year later at the Santa Barbara courthouse. Emhoff wore a flower garland around his neck to honour Kamala’s Indian heritage; at the end, they smashed a glass per Emhoff’s Jewish tradition. It was ritual of compromise in pursuit of unity; an exchange of promises that would be tested sometime in the weeks and months and years to come. All eyes were on Kamala, but Maya was there, too, making sure everything happened the way it was supposed to.

She officiated the ceremony. She even helped write the vows.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments