From iron bars to Ironman: How a prison rowing machine turned a career criminal into a record-breaking triathlete

At 16, John McAvoy owned a sawn-off shotgun and spent his time doing grunt work... at 18 he was handed two life sentences. Now he’s the only Nike-sponsored Ironman triathlete. He tells Josie Cox his story

On a blustery lunchtime in early autumn John McAvoy greets me in the entrance hall of Fulham Reach Boat Club. Sandwiched between an upmarket estate agent and the headquarters of an international spirits company, it’s not somewhere you would expect to find the haunt of sweaty athletes and rugged coaches, but the Thames is there and that’s what matters.

With boyish charm, an impish smile and piercing blue eyes, McAvoy bounces in, energetically pumps my hand, and then – without engaging in inane small talk the way so many interviewees tend to do – he begins telling me about the work the club is doing to support the local community. His passion is unbridled.

Fulham Reach Boat Club’s mission, he tells me, is to help young people realise their sporting potential through rowing. It operates as a charity borne out of an agreement between property developer St George and the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Pupils from local schools who might only know rowing as a sport reserved by the Oxbridge elite and practised once a year on television, can come to the facilities to train, rubbing shoulders with flesh-and-blood Olympians. McAvoy draws my attention to certificates on the walls of the corridor, celebrating records broken by boys and girls who probably never would have touched an oar had it not been for the charity. He’s brimming with pride. You’d be forgiven for thinking we’re discussing his own children.

I’ve come down here today to talk to McAvoy about rowing, and also about his other disciplines. He’s a runner, a cyclist and an Ironman. In fact, he’s the only Nike-sponsored Ironman triathlete in the world. He’s broken world records and a slew of British ones. I want to talk to him about the monumental challenge of competing in endurance sport at an international level and how to retain balance when you’re treating your body like a tireless machine. I want to talk to him about campaigning, education and politics – some of his other interests – but most of all I’ve come to talk to him about his existence before all this: before the shiny boats, protein shakes, personal bests and photo ops. I want to hear about his life as a social outcast, faced with two life sentences. About being labelled as one of most the entrenched armed criminals in British modern history. I’m curious to hear how it feels to know that he could quite easily still be festering behind bars, and that – had it not been for one battered old rowing machine in 2009 – this remarkable case of ultimate redemption may never have materialised and McAvoy would not be sitting in this training room, sock-clad feet resting on an erg machine, patiently answering questions from a disbelieving journalist.

* * *

Even McAvoy admits that his life so far has been rich in cinematics and poor in credibility. Although he has the prison sentences and newspaper clippings to prove the former part, and the records and trophies to do the job for the latter, I find myself repeatedly laughing when he recalls certain film-worthy specifics. “Bloody hell,” I say incredulously as he tells me of being helicoptered to Belmarsh and incarcerated with terrorists and murderers, half expecting him to crack into a smile and tell me he’s only joking. But he doesn’t. “I know,” he replies instead, a nuance of amazement in his own voice. “It’s all a bit mad”.

It’s all experience and a learning curve. I don’t believe in failure as long as you keep going. You either win or you learn

Unless you have an obscure penchant for reading through court documents, McAvoy might well be the most remarkable athlete you’ve never heard of. I first came across him on a podcast. He was a guest and after he’d answered the host’s last question, I hit repeat and listened to the full two and a half hour conversation again. I feel like I know McAvoy’s story well. I incessantly googled him before meeting him (you would too if you were meeting a felon), read press coverage and skimmed a memoir he’s recently published. But I couldn’t resist asking him to tell me his story again, in his own words.

McAvoy was born in southeast London, in 1983, a month after his biological dad’s sudden death. He grew up with his mum and stepsister and describes his childhood as “fairly normal”, apart from the fact that he had no father, something for which he was teased at school. But he was doted upon by other family members: aunts and uncles, and his mother, with whom to this day he has loving relationship.

When McAvoy was eight years old, his mum’s first husband – the father of his stepsister – walked through the family’s front door and into his life, transforming it irreversibly. Billy Tobin had no son of his own so immediately became a father figure to McAvoy. McAvoy, in turn, looked up to Billy, admiring his larger-than-life persona and his confidence.

“Billy was rich. Billy had everything,” McAvoy tells me today. “He was always dressed immaculately and had money, cars and property. I idolised him. He was the person I wanted to be when I grew up.” At the time McAvoy was oblivious to the fact that Billy had just been released from prison.

By his own admission McAvoy wasn’t an academic child, but even as a schoolboy he fostered a profound interest in history. His mother would buy him magazines in which he would read about the individuals who shaped the world – Napoleon, Churchill and Hitler. He was fascinated by strategy (he tells me he would obsess over questions like why Hitler didn’t win the war) and by the fact that, although these men were mortals, they were able to live on for generations posthumously. With hindsight, McAvoy recognises that this was him discovering the concept of legacy. He too wanted to plant a footprint on the earth which would last when he was gone. He wanted influence. He wanted power to make a difference.

Billy, meanwhile, spared no expense taking the impressionable young McAvoy to London’s finest establishments where the two would mingle with Billy’s friends who were equally rich and charismatic. McAvoy didn’t understand who these men were but he was bewitched by them. They would slip him cash and other gifts. “It’s amazing how your whole life can be completely warped by the people who are around you and influence you,” McAvoy says. “I looked up to these men because I had no alternative. They were my role models and I wanted to be like them. I knew nothing different.”

I recognised many of my own qualities and characteristics in people like Lance Armstrong. Reading about his journey made me realise that I didn’t have to channel those personality traits into crime

Studying McAvoy’s family tree it’s easy to see what he means. Take Mickey McAvoy, McAvoy’s uncle for whom Billy’s friends constantly and passionately expressed their admiration. On the early morning of 26 November 1983, Mickey cemented his spot in the annals of British criminal history by orchestrating a heist of £26m worth of gold bullion, diamonds and cash from a warehouse in Heathrow as a member of the infamous Brink’s-Mat robbery gang. It was chalked up as the crime of the century and, although it has since been eclipsed in scale, it’s still cited as one of the most spectacular pilferages, partly because, while many of the gang members were convicted, most of the loot was never recovered.

McAvoy recalls that in 2004, The Telegraph published an article chronicling the evolution of organised crime in Britain. It singled out five of the most prominent individuals who had shaped the country’s scene in recent decades. Three of those five men, he tells me dolefully, played a part in his upbringing.

But, it was only when McAvoy was 12 that he really started to grasp the identity of his relatives and the nature of their business. While sorting through a chest of drawers after his grandfather’s death, he stumbled upon a stack of newspaper clippings detailing Billy’s robberies and arrests. His stepfather, he realised, had been the scourge of the Flying Squad, the division of the Metropolitan Police dealing with serious and organised crime. His uncle Mickey had been no different, and McAvoy, it seemed, was on course to take over the family business.

* * *

By the time McAvoy was a teenager he had lost all interest in school. Driven by arrogance, greed and an overwhelming determination to do his bit towards overthrowing authority, he started to plan for a life of crime. Billy, convinced that his protégé would be safer operating with his guidance rather than alone or with people his own age, took McAvoy under his wing. A lawful alternative, McAvoy explains, was never even considered.

At the age of 16 McAvoy owned a sawn-off shotgun and spent his time doing legwork, helping the criminals he considered role models to secure the intelligence they needed to perfect their heists. He would observe security vans making deliveries to cash depots around the country, studying schedules and memorising number plates, hiding in plain sight. Security staff, he tells me, tended to look out for stubbly, middle-aged men – caricatures of criminals, Kray lookalikes – and not a pimply, mildly overweight teenager on a motorbike.

No grunt work was too menial or risky for McAvoy. He was a pawn in the wide, complex syndicate. He transported arms from one side of the country to the other with the hope of eventually graduating to more gratifying, high-profile tasks. Today McAvoy reflects that he may well have been the victim of exploitation. After all, he was being treated as a puppet by a throng of megalomaniac men who had been committing crimes for decades, but at the time the prospect of becoming rich and powerful was a driving force too furious to fight.

At 18 McAvoy was slapped with his first prison sentence for possession of firearms. A plot to rob a bank was foiled by the police. McAvoy was chased and caught by an officer on foot. He served three years in prison, of which he spent a year in solitary confinement, initially because he refused to wear clothing identifying him as a flight risk, later because he wouldn’t take up his duties as a wing cleaner. He had endurance, patience and a steely determination not to be tempted into giving the wardens any more power over him than they already had. On Christmas Day, he recalls, he scoffed at a warden’s offer to call his mother. He didn’t want to give the guards anything which they could lord over him, he says. He was hell-bent on not becoming “institutionalised”.

During that first year McAvoy followed the news diligently (“The Times, the Daily Mail and Nick Ferrari,” he tells me), read tirelessly (Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom and other staples on a stereotypical inmate’s reading list) and started dabbling in fitness, doing thousands of sit-ups, step-ups and push-ups, or “cell circuits” as he describes them, mostly to while away the days and “live rather than just exist”. He toned up, got lean, developed a six-pack. He says that when he walked out of prison he was unrecognisable, but it didn’t take long for him to pick up exactly where he left off. He was welcomed back into London’s criminal underworld with open arms and resumed his quest to overthrow the system. He had a moral compass: the man on the street, women and children were always taboo and that was non-negotiable. But police, politicians, bankers and large corporations were all fair game.

* * *

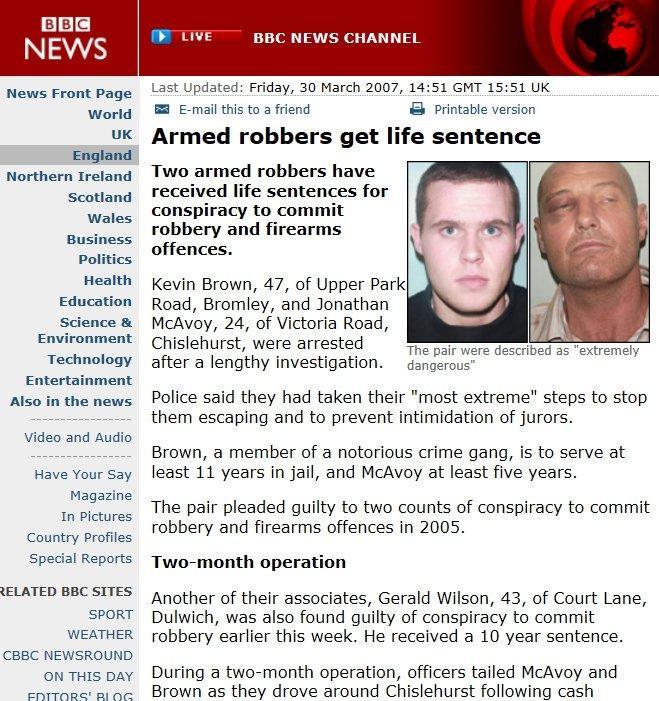

In 2005, a day after returning from a trip to Spain and less than two years after his first release, McAvoy was arrested on Sidcup High Street and, after a lengthy investigation, pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit robbery and one count of possession of firearms with intent to commit robbery. McAvoy says that on the day he was arrested, he had met with Billy Tobin’s friend, Kevin Brown, a member of the infamous Untouchables crime gang, who had convinced McAvoy to help him with a major heist. McAvoy tells me that he initially declined to cooperate, but Kevin managed to convince him. Not long after, police ambushed the pair and held them at the police station for three days before both they were sent to Belmarsh by helicopter.

McAvoy recalls now that when he was handed his two life sentences and declared a double category A prisoner – the most dangerous type – he was in denial. Arrogance, he says, kept him from believing that his future was behind bars. He says that he fostered so much hatred towards the legal system, the judge and authority, that he refused to believe they could topple him. No doubt like others who share McAvoy’s predicament, his priority was therefore to hatch an escape plan. It would be an understatement to say the odds were stacked against him.

Belmarsh’s walls are famously impenetrable. In the early 2000s, the prison was used to lock up people indefinitely and without charge under the provisions of the anti-terrorism act, earning it a reputation as Britain’s answer to Guantanamo. Although Jeffrey Archer is perhaps Belmarsh’s best known resident, Ian Huntley, the child killer, was sent there too. McAvoy was held in the same quarters and conditions as Islamic fundamentalist Abu Hamza al-Masri and individuals involved in a plot to blow up transatlantic flights with bombs disguised as soft drinks. McAvoy was neither a murderer nor a rapist, but due to his extensive connections within Britain’s criminal underworld, he was deemed an exceptionally high escape risk. He was considered a danger to the police and the public, and the chances of him ever changing, the wardens said, were negligible.

After two years in the highest security section of Belmarsh McAvoy was moved to another prison, where he was granted a greater degree of freedom. He continued to plot his escape, but in 2009 one of McAvoy’s closest friends was killed during an attempted heist in the Netherlands. McAvoy was deeply struck by the loss and became acutely aware of the fact that he did not want to follow in his friend’s footsteps. Life, he says, took on a new sense of fragility and that was a powerful catalyst for change. Almost overnight his attitude shifted. He became aware of the fact that there was an alternative to crime. He started seeking distance from his fellow inmates, isolating himself and focusing on the academic opportunities available to him behind bars. But it was tough. He likens the experience to being “an addict stuck in a crack den”. His inmates constantly discussed the crimes they would commit as soon as they got out. McAvoy, meanwhile, just wanted to change.

* * *

As a youngster McAvoy was never an athlete and, although he developed a schoolboy’s interest in football, he admits that he was always somewhat overweight and the last to be picked for the team. That makes it all the more surprising perhaps, that when he first got on the rowing machine and hesitantly found a slow steady rhythm, something triggered. It was just days after the news of his friend’s death had broken and going to the prison gym had been a feeble attempt at distraction. When he started rowing, he explains today, he almost instantly entered what he recognises with hindsight as a state of near meditation. He was transported beyond the prison walls to anywhere in the world. All that mattered was the pumping of his muscles, the push and pull of his breath and the energy building up within his body. On that first day he rowed 32 kilometres. He was hooked.

There’s ample evidence underscoring sport’s positive impact on mental health. In September this year, a comprehensive Swedish study concluded that exercise, specifically yoga, can significantly reduce inmates’ levels of psychological distress and thereby quell obsessive-compulsive behaviour and paranoid thinking, in turn reducing the risk of re-offence. But when McAvoy first sat on the rowing machine, he had no concept of just how much of a literal lifeline this seemingly innocuous piece of equipment would become. Though he was oblivious to the science, the endorphin rush of the physical exertion stabilised his moods. Later, after months of training, when he realised that he has a physiological predisposition to being able to row exceptionally long distances and tolerate a high level of discomfort over an extended period of time – not to mention boredom, he stresses – setting goals and striving to reach them gave him a greater purpose than mere survival.

During his first month of rowing, McAvoy covered a million metres. Four months later he’d rowed the equivalent of the distance across the Atlantic. He raised money for a children’s charity and his life beyond the prison’s gym changed too. He developed a passion for the study of physiology and the power of the human body, lapping up textbooks and memoirs of exceptional athletes. He says that the biography of Lance Armstrong had a particularly profound impact on him: “I recognised many of my own qualities and characteristics in people like Lance Armstrong. Reading about his journey made me realise that I didn’t have to channel those personality traits into crime. That’s when I realised I wanted to be an athlete.”

That discipline and determination paid off. Within 16 months of starting to row, McAvoy had broken three world records and eight British ones. He smashed the record for the fastest marathon on an indoor rowing machine by seven minutes. He also crushed the record for the longest continuous row (45 hours) and the furthest distance rowed over 24 hours (265 kilometres). He still holds many British records.

By the time the parole board considered his request for release in 2010, he was convinced that endurance sport was his future and that he would become a professional athlete. Initially, however that aspiration proved a stumbling block. A prison psychiatrist said that his ambition was not “rooted in reality” and denied his request, but he was transferred to an open prison giving him the opportunity to leave the facilities during the day, get a job and start the sluggish process of re-acclimatising to life outside.

Through a reintegration programme McAvoy managed to get a job as a personal trainer at a Fitness First gym in Derbyshire, not far from HM Prison Sudbury where he was serving his sentence.

McAvoy would leave the prison in the morning, head to the local library for half an hour where he would read blogs, books and websites about endurance athletes, nutrition, recovery and rehabilitation, before heading to the gym where he trained clients. It was during that time that he met Terry Williamson, a sports performance psychologist and yoga enthusiast who now works closely with McAvoy as part of his coaching team.

Though McAvoy was cautious in his approach to newfound freedom, his hunger for physical challenge was becoming ferocious. While still at Sudbury he was granted permission to run an ultramarathon from London to Brighton – around 60 miles. Unsurprising for someone with his willpower, and despite still knowing very little about the toil of long-distance running, he completed the course. Rather sheepishly he admits, however, that he had to descend the South Downs backwards. His quads, he recalls painfully, simply couldn’t handle it.

* * *

In 2012, after almost a decade behind bars, McAvoy was finally granted parole. It was a Friday. On Saturday he headed down to Putney Town rowing club in southwest London. The club has a rich history of training some of the UK’s most promising athletes but even so, McAvoy’s times were praiseworthy. Across 2,000 metres his personal best was 14 seconds faster than the qualifying time for the Great Britain national squad, he tells me. Over 5,000 metres his time was more than 30 seconds faster. But for McAvoy it quickly became clear that age and technique were not on his side and that if he wanted to forge a career as an athlete he would have to be strategic. He set his sights on the triathlon, glossing over the facts that he couldn’t ride a bike and had rarely run more than 10 kilometres – and that on a prison treadmill. At the age of 30 he bought his first bike off eBay and learned to ride. He taught himself to swim with the help of YouTube. Slightly embarrassed but also with a hint of pride he admits that, in his early days on the bike, he would descend hills slower than he would climb them during training camps, out of fear of crashing.

In early 2013 McAvoy made his Ironman debut in the UK. He swam 2.4 miles, biked 112 and ran 26.2 in 11 hours and 49 minutes, ranking 287th out of just over 1,300 finishers. By 2016 in Frankfurt, McAvoy had shaved almost two hours off his time and was on the brink of cracking the three-hour mark for the marathon. Last year, back at Ironman UK, he ranked 36th overall out of more than 1,700 finishers. A gradually growing media presence won him a Nike sponsorship contract – a clear career highlight. Now he travels the world competing, making speeches and hosting workshops as the only Nike-sponsored Ironman triathlete. It’s almost comical to think that he still has to ask his parole officer for permission to leave the country every time he embarks on an international excursion. It’s hard to believe he’s still serving two life sentences.

But although McAvoy has overcome immense adversity, his life since leaving prison has not been without challenges either. In 2014 he became a victim of his own discipline when he suffered severe burnout from over-training. He was admitted to hospital and diagnosed with post-viral exhaustion. The experience was humiliating and humbling, he says, but he slowly rebuilt his strength. He got a coach and he’s since adopted a much more mindful approach to training, despite still covering hundred of kilometres a week on bike and foot. Last year, he says, he took 12 days off training completely. These days, he adds, he might on some days “just go for a 10k run”.

Away from the tracks, roads and water, he’s particularly proud of the work he’s done in campaigning for prison reform. He’s a sought-after motivational speaker. He recently spoke at the House of Commons. He visits prisons and correctional facilities regularly. He tells me that because of his own past, offenders don’t consider him a figure of authority and often open up to him. He explains that this gives him access to them and means that he can, in some cases, offer guidance on how they too can reshape their lives. When I ask him what his most rewarding experience has been so far, he says that there are too many to count. All the kids he’s worked with, he says, “are amazing”.

Finally, I ask McAvoy a question I’ve been wanting to know the answer to for a long time. Does he regret the crimes he committed as a young man? At first it might seem like a strange question: the conscientious, engaged, athlete sitting before me clearly has the lucidity to recognise that what he did back then was wrong. But it’s also unlikely that McAvoy would have ended up with the life he’s currently leading if had he not been a felon. So if he could go back, would he? Characteristically succinct, he says, simply, that he has “no regrets”.

“It’s all experience and a learning curve,” he explains. “I don’t believe in failure as long as you keep going. You either win or you learn.”

McAvoy has left no one in doubt that he’s done plenty of the latter. As he gets up and prepares for his next training session, I’m sure that the next few years will be all about the former. It would take a brave person or a fool to challenge John McAvoy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments