Jeremy Corbyn: How Britain’s struggle for black civil rights helped shape the messiah of millennials

Tony Blair says Labour is in a worse state now than it was under Michael Foot in the Eighties. Robin Bunce wonders whether Corbyn’s decades-long relationship with the fight for black empowerment suggests it is simply ahead of the curve

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jeremy Corbyn is an enigma. Even the fact that people are still writing about him is perplexing. On entering Labour’s leadership contest in 2016, he was written off as a rank outsider. When he won, it was widely agreed he would only last a fortnight. After a month, pundits predicted a splinter group of disgruntled centrists setting up a new party.

Come general election last year, the smart money was on a Labour wipe-out: even worse than the one in 1983 under Michael Foot. After all, how could an avowed left-winger survive the combined attack of a popular Conservative Prime Minister and the Tory Press? Yet survive he did.

One reason such predictions were so out of whack is that Corbyn’s politics are misunderstood. From comparisons with Foot, the narrative shifted. His second leadership victory was quickly attributed to the influence of Trotskyite entryists, extremists similar to the Militant group that caused Neil Kinnock, who was keen to steer the party away from Foot’s mistakes, so much grief.

Corbyn was dubbed a populist. Philip Hammond misses no opportunity to remind voters of “old Labour” and the turmoil of the 1970s. But likening Corbyn to Foot, or Militant, or “old Labour” is profoundly wrongheaded. Not only is an amalgam of Foot, Militant and James Callaghan inconceivable as they represent radically different and ultimately antithetical positions, Corbyn comes from a wholly different wing of the labour movement.

To understand Corbyn, look no further than the backdrop against which he arrived.

Margaret Thatcher bringing the Conservatives into power in 1979 is widely regarded as a decisive break from the post-war, cross-party consensus that tolerated strong unions and a generous welfare state.

This, however, is not the whole story. For the late left-wing thinker Stuart Hall, the late Sixties and early Seventies were the true watersheds. It was then that the Black Power movement, the Gay Liberation Front, the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland, second wave feminist groups, and the anti-Vietnam war movement pushed their way into mainstream debate.

Harold Wilson’s technocratic approach to socialism had failed to reverse Britain’s economic decline. As the economy nosedived in the early Seventies, the right responded by arguing that Britain’s economic malaise was rooted in a social crisis – one created by immigrants, Irish nationalists, militant trade unionists, radical students and extreme feminists who were hellbent on wrecking the nation.

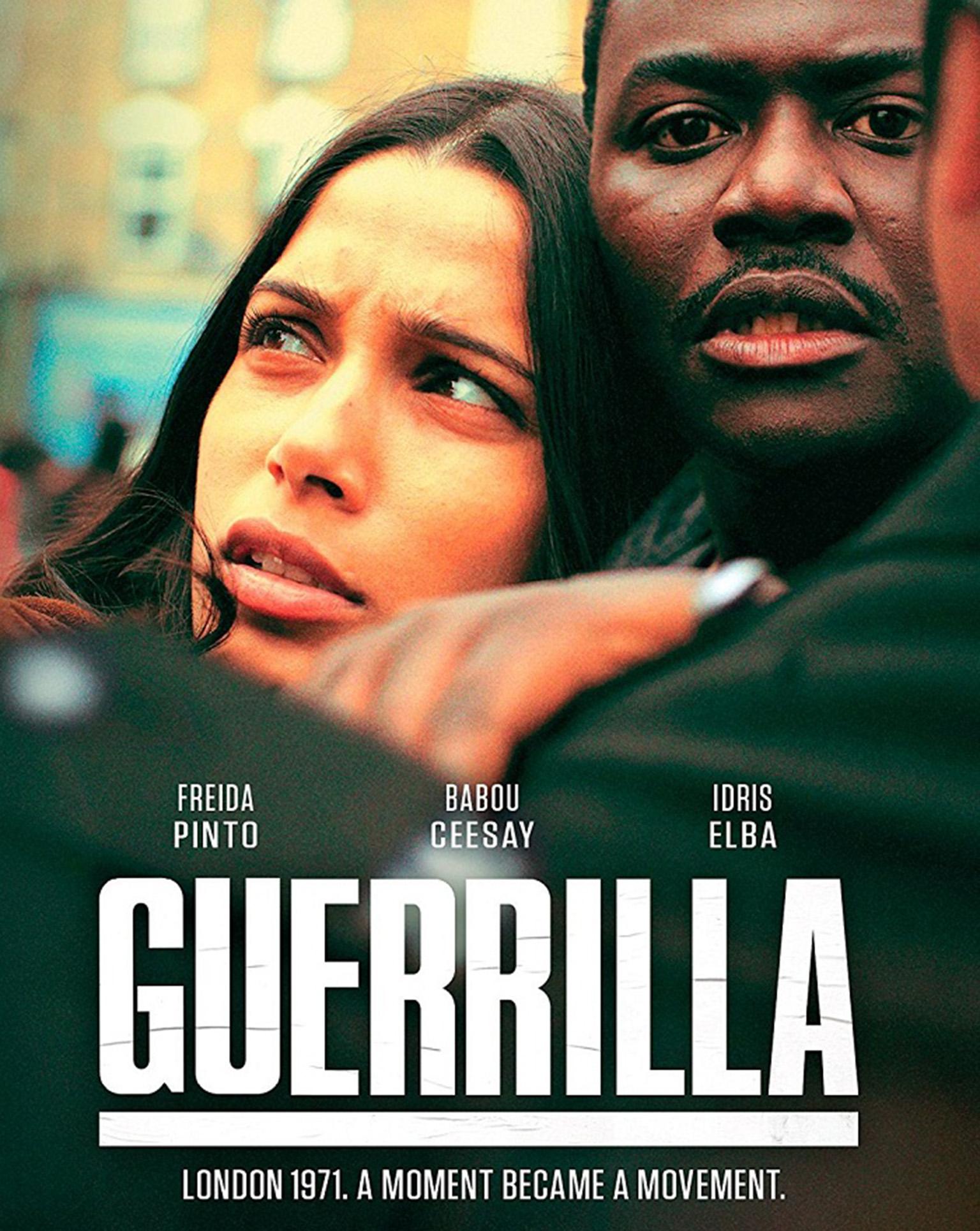

For example, Britain’s black civil rights struggle – the backdrop for a Sky Atlantic miniseries Guerrilla last year – was demonised. Scotland Yard had a dedicated black power desk.

As black power campaigner Leila Hassan led marchers to the US embassy in protest against the imprisonment of the American Black Panther Angela Davis, as Darcus Howe and Althea Jones-Lecointe led protest marches through west London against police brutality, some newspapers went as far as to suggest London would soon be Balkanized, divided into armed camps along ethnic lines.

(Howe and Jones-Lecointe were part of the “Mangrove Nine”, named after the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill which regularly was subjected to police raids and became a focal point for the black community – after a 55-day trial at the Old Bailey in 1970 they were acquitted of the charge of inciting a riot.)

Enoch Powell had expressed the most radical vision of social disharmony in his “rivers of blood” speech in 1968. He also argued that having defeated Nazism, Britain was under attack from within. For Powell immigrants from “new Commonwealth” countries were undesirable – unlike those from Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. He advocated the repatriation of black and Asian migrants. And he was not alone.

The 1971 Immigration Act, passed by the Conservatives under Ted Heath, ended the automatic right of citizens from Commonwealth countries to remain in Britain. The discourse of Conservative politicians who argued that Britain was under siege, in danger of being “swamped” by immigrants and sabotaged by left-wingers, was one Thatcher endorsed.

Jeremy Corbyn’s politics were similarly informed amid the debate about Britain’s “crisis”. While populists on the right sought to present minority groups and organised labour as a threat to the nation, radicals on the left took a different tack. The Labour left argued that Britain’s problems were rooted in an economic crisis of capitalism. What is more, Labour politicians around Tony Benn began to argue that expanding political participation was the key to egalitarian economic reform. Simply put, the more working people were involved in politics, the more economic policy would serve their interests.

By the early 1980s groups such as the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy, and grassroots publications including London Labour Briefing had concluded that Labour needed to be more representative of the country it sought to govern. Only when black people, women, gay men and lesbian women played a key role in creating policy, only when minorities were represented in Parliament, and throughout government, and the party was democratised would Labour be able to build an economy that truly worked for all. In practice this meant that Benn and his supporters threw their weight behind the “black sections”, which aimed to empower ethnic minorities within the Labour party; openly gay candidates, the demand for all-women shortlists, and measures such as the mandatory reselection of MPs.

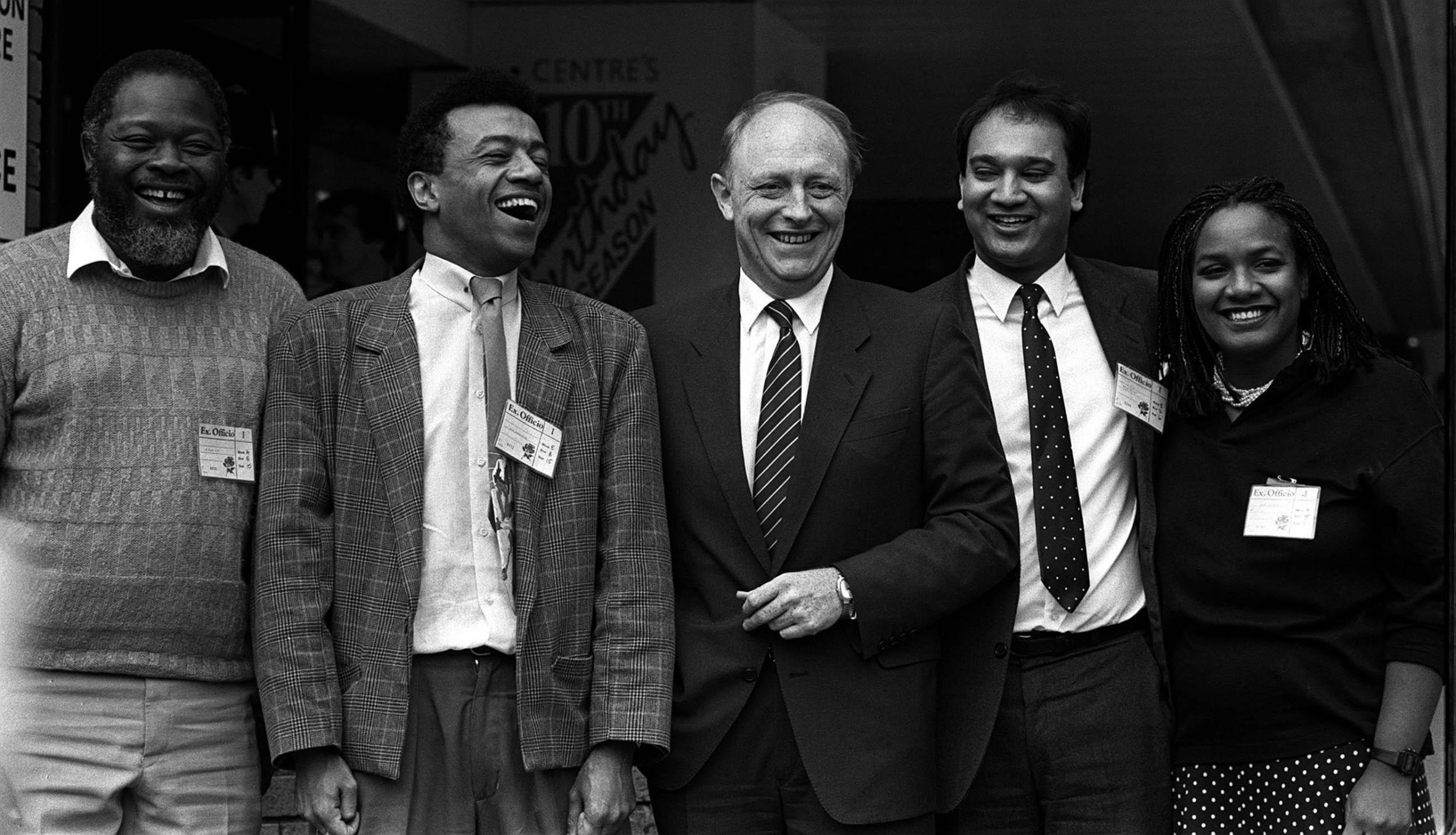

Labour’s debate around black sections highlighted differences between radicals such as Corbyn and his mentor Benn on the one hand, and Neil Kinnock and supporters of Militant on the other. The campaign for black sections emerged in 1983, as black activists sought ways to influence the direction of the party.

Campaigners argued that Labour’s black members should have the right to organise a Section with a formal voice at all levels of the Party. Women and students already had Sections with representatives on the National Executive Committee; black activists wanted the same. Leading figures in the campaign for Black Sections, such as Diane Abbott, argued that Labour’s traditional emphasis on “universal” benefits and services had tended to advantage white traditional families, rather than working women, lone parents, black people, or those working in service industries.

Linda Bellos, vice chair of the Black Sections Campaign, argued that black sections were essential to guarantee that the party was responsive to the concerns of black voters. The campaign also organised to ensure that Labour selected black parliamentary candidates, and increased the representation of black people in local government.

Informal black sections formed quickly in Vauxhall, Hackney and Lambeth in London, Birmingham, Liverpool, and other UK cities. Black sections were open to all people who had been historically oppressed by colonialism. In some areas, Black sections were predominantly African-Caribbean, in others largely Bengali; Cypriots were also welcomed as comrades. This understanding of black as a “political colour” reflected the orientation of earlier British movements such as the Black Panthers and the Black Unity and Freedom Party.

Black sections tended to see themselves as part of a rainbow coalition, supporting striking miners in Britain and South Africa; and as allies of feminists and lesbian and gay activists. Indeed, black sections were informed by black feminism. Leading members of the movement, such as Abbott and Martha Osamor, had been involved with the influential Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent from its formation in the late Seventies.

Initially the Labour Party leadership appeared sympathetic. However, the right-wing press quickly vilified the campaign. For papers like the Daily Mail any willingness to listen to black activists, lesbian and gay activists, activists with disabilities, or feminists showed that Labour no longer spoke for “ordinary people”. What is more, after the 1983 defeat under Foot, Kinnock was keen to shed Labour’s left-wing image. So he attempted to block black sections, characterising the initiative as a form of apartheid.

Speaking for black sections at the 1984 Labour conference, Elaine Foster countered Kinnock’s argument. Rather than being a form of apartheid, she claimed, the campaign for black sections championed the right of black members to “participate in the Labour Party on our terms, on equal terms”. Having failed to quash the campaign, the leadership intervened to deselect Sharon Atkin and Martha Osamor, who looked likely to become Labour MPs.

While the leadership blocked black sections at a national level, the initiative flourished locally. Black sections became part of the new “urban left” which won control of many of Labour’s inner-city councils. Local government under Linda Bellos, Bernie Grant, and Hilda Kean, and most famously the GLC under Ken Livingstone exemplified the new “municipal socialism”.

Aware of the failings of previous Labour governments, the new generation of radicals advocated a more decentralised, democratic and inclusive form of socialism which would turn local government into a bulwark against Thatcherism.

Lambeth council in south London, for example, adopted Equal Opportunity employment policies, and monitored local services to stamp out discrimination. The Greater London Council led the way nationally in democratising housing policy, ensuring that local people were able to work with architects to design their own homes.

Its leader Ken Livingstone tried to tie popular initiatives to progressive goals. The “Fares Fair” policy significantly reduced the cost of public transport, and in so doing reduced traffic pollution. Similarly, the GLC funded childcare schemes, often by providing funding to women’s groups, including many black women’s groups. This made childcare cheaper, providing support for working women and lone parents. The GLC canteen, which provided subsidised food for local government workers, was opened to the public, and Livingstone spent the budget allocated by government to prepare the capital for nuclear attack on a campaign promoting nuclear disarmament.

The GLC also funded voluntary groups representing minorities. Such empowerment was central to the vision of a more democratic society, in which government responds to the interests of a diverse population.

The new radicalism was an embarrassment to the Labour leadership. The right-wing press attacked “loony left” councils, and championed Conservative plans to constrain local government. The Conservatives promised to abolish the GLC as it was “wasting” public funds supporting “alternative lifestyles”, which were at best misguided and at worst an immoral assault on the “traditional family”. They also introduced Section 28, which David Cameron apologised for in 2010. It prohibited the promotion of homosexuality by local government, and banned schools from teaching the “acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”.

In 1987 the loss of Greenwich in by-election – a safe Labour seat since 1945 – convinced Kinnock that the party’s association with gay liberation and black rights was an electoral liability. The SDP-Liberal Alliance, forerunners of the Liberal Democrats, won the by-election by campaigning as a moderate alternative to Labour’s “loony left” extremism. The Alliance tried a similar strategy at the 1987 general election, attacking Diane Abbott, to take one example, on the basis that she did not represent “ordinary” voters.

Corbyn was very much part of this radical milieu. He worked closely with Abbott and Bernie Grant. Together with Benn, Livingstone and Abbott, he wrote for Socialist Campaign Group News, a paper that continued to make the case that Labour should be more democratic and representative of the country.

So it’s fair to say Corbyn has been misunderstood. Associating him with “old Labour” misses the point that he comes from a wing of the party which recognised the problems with the centralising approach of the Callaghan and Wilson years; and the “universalism” of the Atlee government.

Associating him with Militant ignores the fact that Militant was wholly opposed to the new politics of representation which was championed by Corbyn and his allies from the 1980s. Finally, rather than being a populist, Corbyn’s politics is a democratic challenge to populism. Populists argue that the rights of “ordinary people” have been usurped by minorities in league with the elite.

Populists characterise minority groups as dangerous and their demands as inherently illegitimate. Corbyn, by contrast, wants a politics in which minority groups play a key role. For Corbyn, democracy cannot be reduced to a national vote once every five years, nor can the “will of the people” be reduced to crude majoritarianism.

Britain is diverse, therefore democracy is also about groups organising themselves, articulating their own agendas, and making their voices heard. So rather than demonising minorities, and claiming that their demands are illegitimate Corbyn wants a fuller democracy, a wider electorate including groups like students, which have historically been disenfranchised.

Kinnock viewed the loss of Greenwich as proof that this strategy could never work. Last year Labour’s victory in Canterbury – a perennial safe Conservative seat – points in a different direction. Corbyn should indeed be understood as a radical democrat who believes that only a truly representative government can work for the many not the few.

Robin Bunce is a research associate at Homerton College, University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments