Is this chimpanzee a non-human person?

Scientists tell us several species demonstrate high levels of intelligence, leading some to consider whether they deserve to have a few of the same rights as humans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This week, the long-running saga of who owns the “monkey selfie” finally reached a settlement.

David Slater had entered into a legal dispute over the rights to the image, with Wikipedia and then People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta) claiming it belonged to Naruto, the crested black macaque who had taken Slater’s camera and shot the picture himself.

The six-year long dispute finally ended with an agreement that Slater will pay 25 per cent of the royalties of the image to conservation charities working on saving the monkey’s natural habitat. Prior to the case put forward by Peta, the US Copyright Office had ruled in the favour of David Slater.

In a joint statement, Slater and Peta said: "We must recognise appropriate fundamental legal rights for them as our fellow global occupants and members of their own nations who want only to live their lives and be with their families."

The selfie dispute is one of a number of recent cases involving the legal rights of animals.

In June this year, an appeals court in Manhattan was tasked with making an unusual ruling – to determine whether two chimpanzees should be considered non-human persons in the eyes of the law.

The aim of the plea was to secure freedom for Tommy and Kiko, which the Nonhuman Rights Project alleged had been illegally locked up at two locations in the state of New York. Kiko, a former performing chimpanzee was allegedly being held in a private home in the state’s Niagara Falls district, while the group said Tommy was in a cement and steel cage in a trailer park.

Steven Wise, the founder and an attorney for the Nonhuman Rights Project argued that the apes deserved habeas corpus – which would relieve them of what he described as unlawful imprisonment.

The ruling hinged upon whether Tommy and Kiko could be best understood as “persons” or “things”. It is this fundamental conception of where animals are placed within both the US and most other legal systems that is the focus of the Nonhuman Rights Project’s efforts, as Wise explains to me.

“Since Roman times, the world has been divided into things that lack the capacity for any legal rights, and persons who have the capacity for an infinite number of human rights.

“Non-human animals have always been things, which means they have always lacked the capacity for legal rights. Sometimes humans have also been things – women, children and slaves for example. Now all humans are persons and all non-human animals are things.

“When you’re a thing, you don’t count in law, your value is not inherent or intrinsic, your value is the value that the persons give you. You are a slave to the person, who is a master. Even your most fundamental interests are not protected.”

Key to Wise’s argument is the extent to which these animals are understood to be autonomous beings. Determining an animal’s autonomy is often subjective – as it is with humans – but most scientists are agreed on a few basic principles that show what we understand to be autonomy in other animals. A capacity to learn, to be self-conscious, to problem solve, to be capable of being aware of the past and anticipating the future, exist as a social group, display primitive forms of language and the development of distinct “cultures” are all thought to be indicators of an animal’s autonomy.

Chimpanzees are believed to be our closest living relatives, capable of using sticks and tools, adopting basic sign language and living within advanced social structures. The court in Manhattan agreed that chimpanzees share emotional, behavioural and cognitive similarities with humans but still turned down the appeal, voting to uphold the lower court’s decision by 5-0.

In explaining their decision, Justice Troy Webber wrote: “So far as legal theory is concerned, a person is any being whom the law regards as capable of rights and duties. Needless to say, unlike human beings, chimpanzees cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities or be held accountable for their actions.”

“Petitioner argues that the ability to acknowledge a legal duty or legal responsibility should not be determinative of entitlement to habeas relief, since, for example, infants cannot comprehend that they owe duties or responsibilities and a comatose person lacks sentience, yet both have legal rights”.

The NonHuman Rights Project dismissed this particular objection, pointing to the precedent set by Salmond on Jurisprudence, which says that a person is a person if they have rights or responsibilities, rather than one or the other. Wise says the court had based its decision on an inaccurate section of an edition of Black’s Law Dictionary, which stated both rights and responsibility are required for personhood. The next edition of the dictionary is being corrected.

Webber also argued that the federal or state legislative process would be a better vehicle for determining whether animals should be given personhood, rather than the courts.

While the case for Tommy and Kiko may have been lost (they have gone to appeal), an Argentinian court decided in 2014 that an orangutan named Sandra is a non-human person with rights, and could no longer be held captive in the Buenos Aires zoo where she had lived for 20 years.

The judge threw out the case for habeas corpus, and instead focused on whether Sandra was a “person” or a “thing”, eventually determining that she was closer to personhood. A hybrid orangutan resulting in the crossing of Bornean and Sumatran individuals, Sandra still remains in captivity while the zoo, which is closing down, decides what to do with her.

Last year, another landmark ruling in Argentina determined that Cecilia, a captive chimpanzee, was entitled to habeas corpus and should be moved out of a cage in the controversial Mendoza zoo and released at the Great Ape Project’s sanctuary in Brazil. In explaining the ruling, Judge Mauricio quoted the philosopher Emmanuel Kant: “We may judge the heart of a man by his treatment of animals.”

In July this year, Luis Domingo Maldonado, a professor of law at the Universidad Manuela Beltrán secured a writ of habeas corpus and recognition of fundamental rights for Chucho, a captive spectacled bear in Colombia. For Wise, rulings such as these put animals on an entirely different legal footing than the protections afforded to most of them today.

“There are times in which we want to decide we want to treat certain non-human animals in certain ways, such as the family dog” he says. “But they are really being protected at our whim, if we decide not to protect them, they won’t be protected.”

“In the United States, President Trump used his pen [took executive orders] to take away a large number of protections given to animals through national parks and wildlife preserves. When he tried to do that with human beings the courts said: no way – they have rights.”

Chimpanzees, orangutan and bears are not the only animals in consideration for non-human rights. Dogs, pigs, gibbons, bonobos, elephants, whales and dolphins have all been considered candidates for personhood by various organisations around the world. Some of the more surprising candidates for legal recognition include the African grey parrot, the Eurasian magpie and species of octopus.

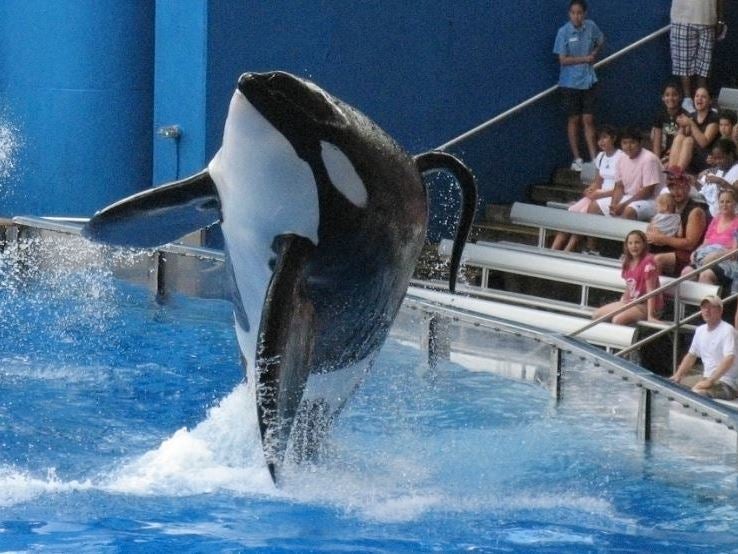

Cetaceans, the group of marine mammals that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises, have been known to exhibit a range of intelligent behaviours, both in captivity and in the wild. Descended from a common horse-like ancestor, these animals have developed complex social lives, hunting techniques and advanced responses to interactions in captivity which scientists say shows intelligence, emotions and a higher self-awareness than is found in most of the animal kingdom.

Bottlenose dolphins and orcas kept in captivity have been shown to pass the “mirror test” – the ability to recognise themselves in a mirror, which is believed to show a strong sense of self-awareness. Apart from dolphins and humans, only the great apes and one Asiatic elephant have been known to pass the test.

The ways in which whales and dolphins communicate and learn specific dialects and behaviours intrinsic to one particular population also shows a level of intelligence, with one Dalhousie University study concluding: “The complex and stable vocal and behavioural cultures of sympatric groups of killer whales (Orcinus orca) appear to have no parallel outside humans and represent an independent evolution of cultural faculties.”

Killer whales are the largest of the dolphin family and also have the second largest and arguably the most developed brains of all whales. By the standards of most mammals, they show an advanced capacity for problem-solving, memory and symbolic language.

The Wiltshire-based charity Whale and Dolphin Conservation has been arguing for countries to take up their Declaration of Cetacean Rights, which argues for the right to life, liberty and wellbeing for all whales. Contained in the declaration is the assertion that no cetacean is the property of a state, corporation, group or individual and not only have the right to protection of their natural environment but also the right not to be “subject to the disruption of their cultures”.

For Wise and his team, killer whales are obvious candidates for non-human rights. “We’re going on a multi-layered attack on the idea that SeaWorld is allowed to own and exploit orcas in San Diego,” he says.

Despite our best efforts at understanding mammalian intelligence, a group of scientists writing in the Animal Cognition journal last month suggested we may have got our facts wrong. Dr David Leavens of the University of Sussex, Professor Kim Bard at the University of Portsmouth and Professor Bill Hopkins of Georgia State University say that a pervasive human supremacism has undermined decades of science aimed at understanding animal’s cognitive abilities.

“The fault underlying decades of research and our understanding of apes' abilities is due to such a strongly held belief in our own superiority, that scientists have come to believe that human babies are more socially capable than ape adults. As humans, we see ourselves as top of the evolutionary tree.

“This had led to a systematic exaltation of the reasoning abilities of human infants, on the one hand, and biased research designs that discriminate against apes, on the other hand.”

Whale and Dolphin Conservation puts forward a similar argument in respect to cetaceans. “One thing to think about is that we need to be careful not to try to measure their intelligence against our own,” the organisation says. “Their intelligence is adapted for the niche in which they inhabit and as far as we know for species like bottlenose dolphins that includes being self-aware and having a good number of spindle neurons in their brain, which we understand are related to the ability to feel empathy towards others.”

For the Nonhuman Rights Project, the determination of which animal “deserves” rights is less important than how the legal framework of a given country ought to treat them. Wise says: “We don’t prepare a case with any preconceived notion of who might count and who should not count. We spend a lot of time trying to understand what the judges say they believe in – what sort of values and principles are in their decisions.

“We then frame our argument in terms of the principles they say they accept. In New York state, the courts really value autonomy, the ability to choose how to live one’s life.”

“If you are in hospital and you decide you want to decline medication or surgery that would save you life and the hospital would go to court arguing that you will die if you don’t go through with their procedure.

“The courts repeatedly refuse to override an individual’s autonomy in this instance, in the case of a competent adult. We then go in armed with affidavits from the greatest chimpanzee cognition researchers in the world and in great detail demonstrate that chimpanzees also are autonomous – that they too can choose how to live their lives.”

Today the Nonhuman Rights Project’s work expands well beyond the US. The group is also working with groups in Portugal, Argentina, the UK, Australia, India, Sweden, Finland Spain and Israel. Their work litigating for chimpanzees in the state of New York continues this month, and they will file their first case on behalf of elephants within the next few months.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments