Could integrated education ease years of sectarianism in Northern Ireland?

Forty years after the first integrated classroom opened its doors, the majority of schools still remain the same. Julie Diamond looks at why it’s so crucial that institutions lose their prejudices

Today marks the 40th anniversary of integrated education in Northern Ireland. Over the course of those 40 years, the integrated education movement has been a slow yet progressive development in Northern Ireland’s unique history.

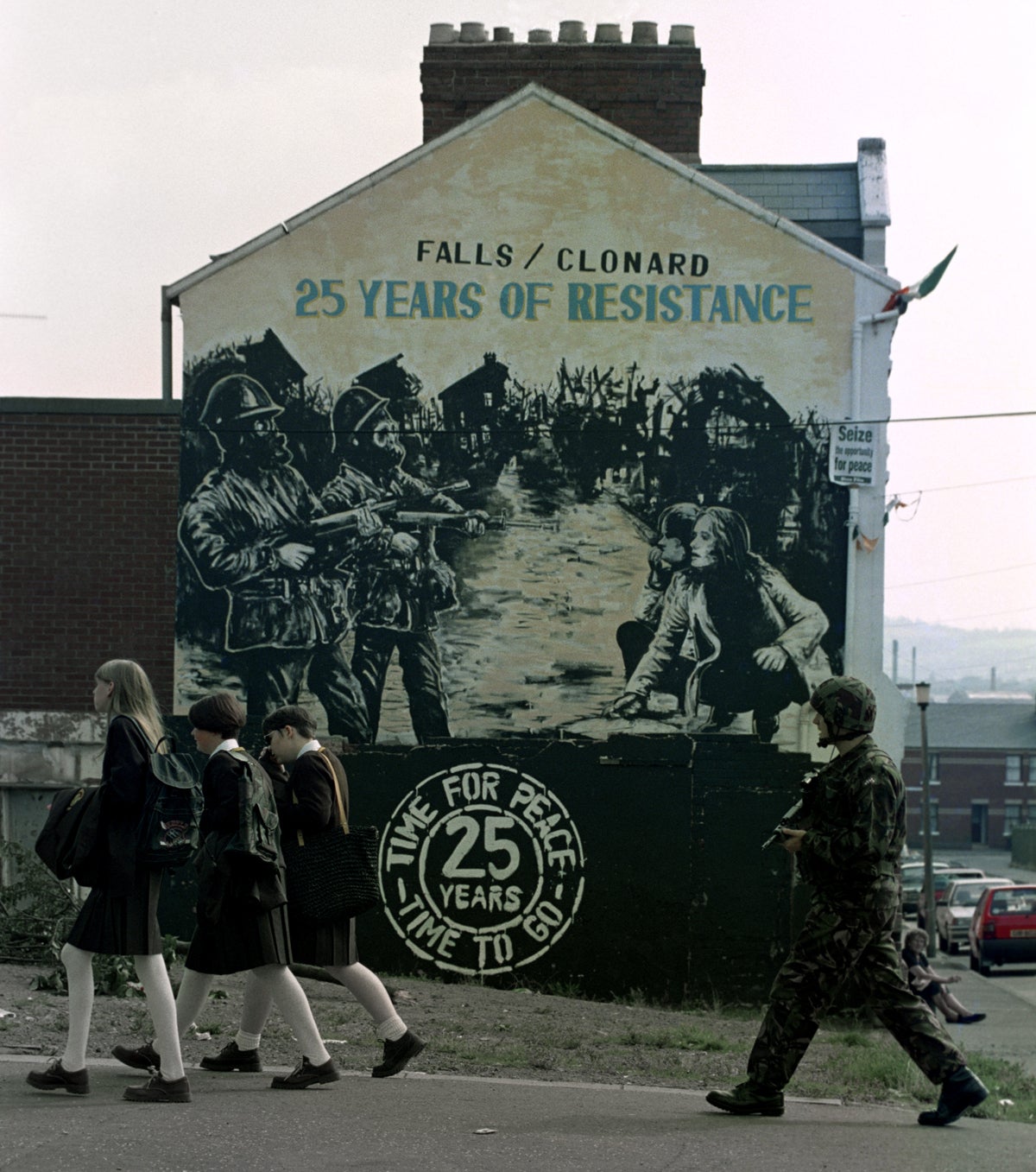

Against the backdrop of the Troubles, communities in Northern Ireland have been largely divided according to religion, with many Catholic and Protestant housing estates separated by peace walls.

Likewise, the education system has been deeply segregated with two conflicting systems, both funded by the state. Traditionally, Catholics attend church schools and Protestants attend controlled schools, with generation after generation growing up and not mixing with the other religion until university or the workplace.

Back in the 1970s, however, at the height of the Troubles, a small group of parents from both sides of the divide came together with the idea to educate children together regardless of religion, in an attempt to break the long history of segregation. Motivated by a shared purpose that learning side by side could foster understanding rather than hatred in a country dogged by sectarian violence, the group of parents became the campaigning group All Children Together.

The group faced opposition from churches and politicians as they challenged traditions that had been deeply embedded in Northern Ireland’s past for decades. Despite these obstacles and with significant financial restraints, against all the odds, the determined parents set up Lagan College in 1981 – the first ever integrated school in Northern Ireland.

One of the founding parents, Anne Odling-Smee, says that despite the obstacles they faced it was very exciting. “People thought we were crazy because we were challenging so many things but the people came, it built up.”

And so in the year defined by hunger strikes and violence on the streets of Belfast, the revolutionary new school was set up on the banks of the River Lagan in a borrowed scout hall with just 28 pupils.

Now, Lagan College has over 1,350 students and is heavily oversubscribed every year, with many former students attending Oxford and Cambridge universities. From this flagship model, there are now 68 integrated schools across Northern Ireland.

Richard Sherry was there on that historic day starting secondary school back in 1981. He says: “It was actually a very momentous day because whenever we started we were told you had to enter the school via the woodland path at the back because there was a protest taking place at the front gates. You had cameras at the front gate as well. Whenever we arrived I think it made everybody feel like celebrities at the time. It’s like whenever you got up there and you saw the protest, and the police patrolling the scout hall, you realised it was like no other school in Belfast.”

You can imagine it, it opens your mind, and you’ve no preconceived ideas. You’re making friends there for the rest of your life

“It was a brave decision by our parents starting a school – they didn’t even have a school building. Twenty-eight pupils and absolutely no money and no backing. There was no backing at all at the time from the education authority, it was just all funding basically.

“It was the best decision ever. Any success I’ve had I can say was largely down to the education I received. You can imagine it, it opens your mind, and you’ve no preconceived ideas. You’re making friends there for the rest of your life. It can only be a good thing. It’s Northern Ireland’s future.”

World champion boxer Carl Frampton, like most people in Northern Ireland, came from a segregated background. He attended a Protestant school, Glengormley High, which is set to become integrated next year. With an interreligious marriage and kids, the world-class boxer returned to his roots this year to back the campaign to transform his old controlled school into an integrated one, and to use his platform to promote integrated education – a topic that he’s passionate about.

“When I went there as a kid I don’t think there was a Catholic, there was no Catholic that I knew of in my year group, and the area is a pretty unionist, loyalist area. If someone had told me when I was a kid that this school is going to be integrated at some point I wouldn’t have believed them, but it’s brilliant.”

“I just feel it’s nonsensical to separate kids in schools and [them] not really come across ‘the other religion’ until they’re sixteen. I was lucky enough I got my integration through boxing, a sport that was an integrated sport and a sport that was open to all.”

Carl talks about growing up in a divided society in North Belfast, with his Protestant community of Tiger’s Bay separated by a peace wall from the neighbouring Catholic area, New Lodge.

“I look back to myself growing up in Tiger’s Bay in Belfast. My mum and dad were good people, but just being in that area where there is tension, division. Without boxing, I probably could have taken a different path and just had a hatred for Catholics and the people in New Lodge for no real reason. Just because other people do in your area and when you’re a kid you’re easily influenced aren’t you.

“I got my integration through boxing but there are kids that are just kind of easy led and easy influenced and it doesn’t necessarily mean they are bad kids when they have these beliefs towards Catholics or Catholics towards Protestants. It’s just the way it is growing up in these areas and when they end up going into the workplace, if they haven’t been in integrated situations before that’s when they’ll develop this understanding but sometimes that’s too late.”

Frampton joins the host of famous faces from the entertainment, arts and sports sectors to use their status to promote integrated education including actor Liam Neeson and Line of Duty star Adrian Dunbar.

Demand for integrated education is high. A recent poll carried out by the Integrated Education Fund shows that 71 per cent of people in Northern Ireland believe that integrated education should be the main model of education.

With increasing demand amongst parents in an ever-changing society and endorsements from celebrities giving up their time to advocate the cause, why is the number of students attending integrated schools still so low after 40 years of campaigning? At present, only 7.5 per cent of children attend integrated education in Northern Ireland.

The Good Friday Agreement of April 1998 stated a commitment: “To encourage and facilitate the development of integrated education.” Despite this pledge, no integrated school has been established by the department of education and there is still no government plan for the integrated education sector. Growth is still down to pioneering parents and determined campaigners working tirelessly on the ground to establish and maintain the schools.

One of the 68 integrated schools in Northern Ireland, Rowandale Integrated Primary School, was set up around 14 years ago by campaigning parents. Starting in humble beginnings like Lagan College, a small group of pupils started in one mobile hut. The school has grown in popularity and is now getting a new building due to its proven success.

I’m not saying integrated education is the magic bullet, but it is a significant part of a solution to the sectarianism in our society

Principal Francis Hughes said: “It’s interesting that even though they agree that you should have a school there’s no plan for integrated education. It was the people on the ground, it was the families, it was the people in the communities that actually made it happen.”

“In the early days there would have been parents coming down and brushing the yard and helping the teachers put things up. It was a huge community feel and a huge community support. Anybody that was sending their kids to the school it wasn’t about the bricks and mortar it was very much about being passionate about sending their children to the integrated school and that resonated really deeply with them.”

In the absence of government planning for integrated education, the Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education (NICIE) and the Integrated Education Fund (IEF) have been a significant support for the movement with campaigning, fundraising and financial funding – helping parents and schools raise vital funds and raise awareness.

Belfast comedian and actor Tim McGarry has helped fundraise for the IEF by performing in comedy nights because he believes in the benefits of integrated education to help break down the barriers in a divided society.

“A majority of people would like to see their schools integrated and the majority of people say that, and I think here’s just a lack of opportunity. The IEF, they fund the schools that are struggling.”

McGarry, a former solicitor who has made a career out of poking fun at the sectarianism in Northern Ireland, says although he had an excellent education in a Catholic school, he didn’t get to know Protestants until he went to university.

“We need to come together and we need to understand each other more. I think the younger people in particular are going what is this, what is this nonsense? I’m still in this situation 23 years after the Good Friday Agreement, Lagan College in 1981, and we still have a segregated society, when it was promised that it would be promoted by the assembly and it hasn’t.”

Although progress has been slow, with no main political party in Northern Ireland backing the campaign, and because it’s been driven by parents and by schools, the movement is still pushing forward with every year that passes generating more integrated schools.

This last year has seen one of the biggest increases in schools becoming integrated. A recent campaign spearheaded by Liam Neeson – Integrate My School – has given parents the power to vote to have their school, either Catholic or Protestant, transformed to integrated status.

In 2021, there have been four schools that have become integrated using this process, including the first-ever Catholic primary school, Seaview Primary School in Glenarm, Ballymena.

Speaking about the recent integration of Seaview Primary, Brian Lambkin – who was the very first teacher at Lagan College in 1981 – describes this breakthrough as “a very encouraging sign”, as he remembers the opposition the campaigning parents faced by the churches back in the Eighties.

Baroness May Blood, a former member of the House of Lords, grew up in a working-class home in the Shankill area of Belfast and is a passionate advocate for integrated education, giving many gripping speeches on the topic. She tells me a story of when she was on a trip to the White House which illustrates her incentive for championing the integrated movement.

“I was on a plane to America, sitting beside a young man who went to an integrated school. I asked him, ‘What was the best thing about integrated education for you?’, and he said it was simple: ‘Integrated education taught me to celebrate other cultures, not fear them.’”

She continues: “This is the way forward. If we can start with children at nursery level, those children will grow up knowing there’s no difference between me and the person beside me. It’s not just Protestant and Catholic, it’s a whole mix.”

With the majority of integrated schools in Northern Ireland oversubscribed every year, Baroness Blood says she wants parents and children to have the option to choose integrated education, which at the moment is not possible for everyone.

“To our knowledge we turned away about 1,500 children that we couldn’t place. Not all our schools are oversubscribed, but the majority would be oversubscribed. Lagan is inundated with people wanting to go, inundated.”

One of the original pioneering parents back in the day, Anne Odling-Smee, shares the sentiment. “I want a choice. Just a choice. You shouldn’t have to go down one or the other. We want people to be able to go to school together as a choice.”

In 2021, as Northern Ireland celebrates its centenary, the future for the integrated education sector remains uncertain. As the story unfolds, the courageous sacrifices made by those pioneering parents back in 1981 can only continue to help build a more harmonious society without fear of “the other side”.

As comedian McGarry sums up: “I’m not saying integrated education is the magic bullet, but it is a significant part of a solution to the sectarianism in our society.”

An Independent Review of Education is due to begin this month, as part of the New Decade New Approach deal outlined by the executive. The review offers supporters of integrated education hope for a change to the current segregated system.

Baroness Blood, who was one of those who fought hard for the review, hopes: “In the next four or five years, if we get this review through and pushing on, which we are, gradually integrated education will no longer become a conversation. It will become a choice. You can either send your child to a state school [Protestant], a Catholic school or an integrated school.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments