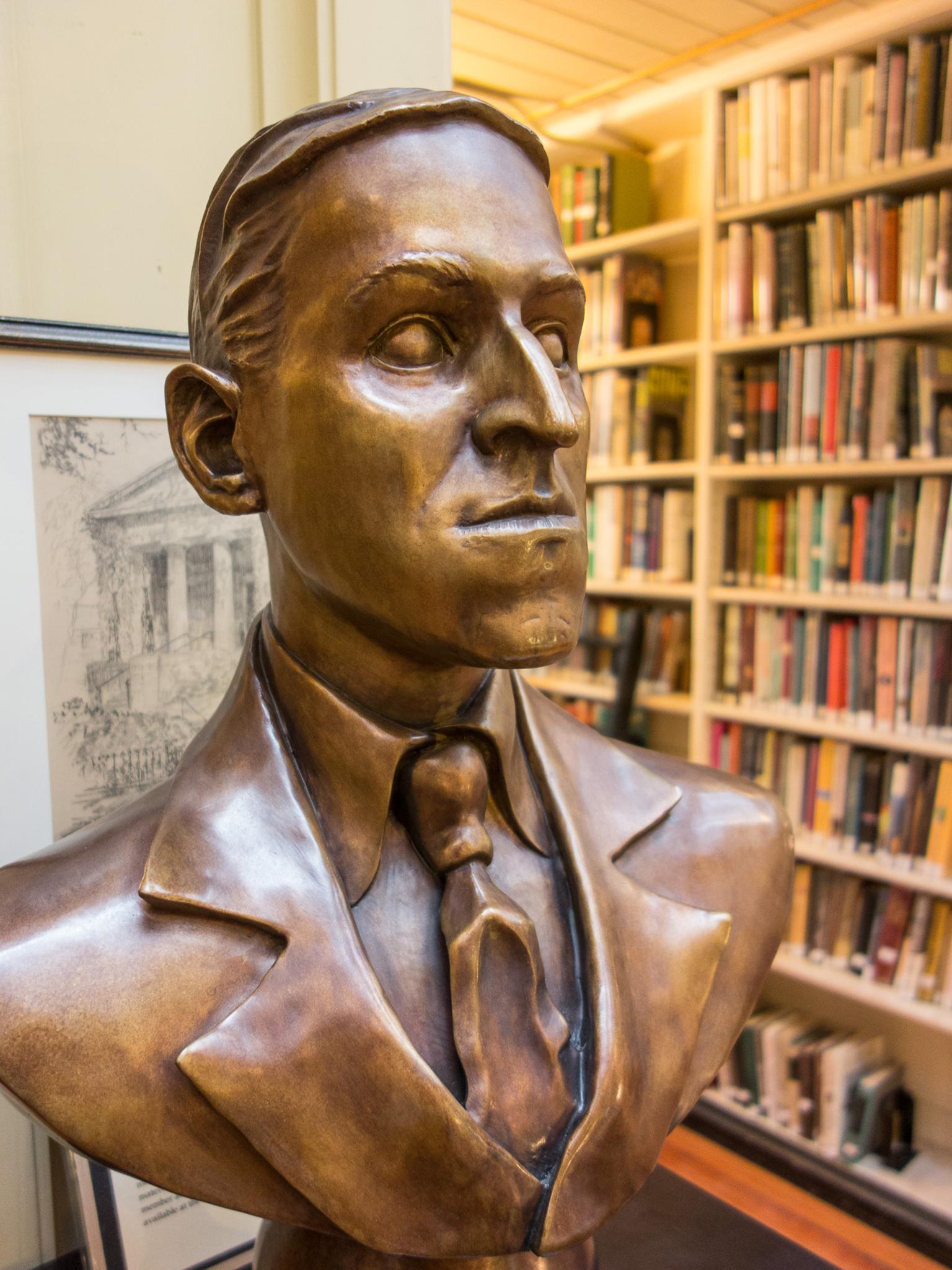

HP Lovecraft remembered: Plumbing the darkness surrounding the horror visionary, reactionary and racist

HP Lovecraft wrote his first story a hundred years ago, leaving a legacy of horror writing that has seeped into popular culture and profoundly influenced cinema and literature to this day. He was also an out-and-out racist. David Barnett peers into the darkness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

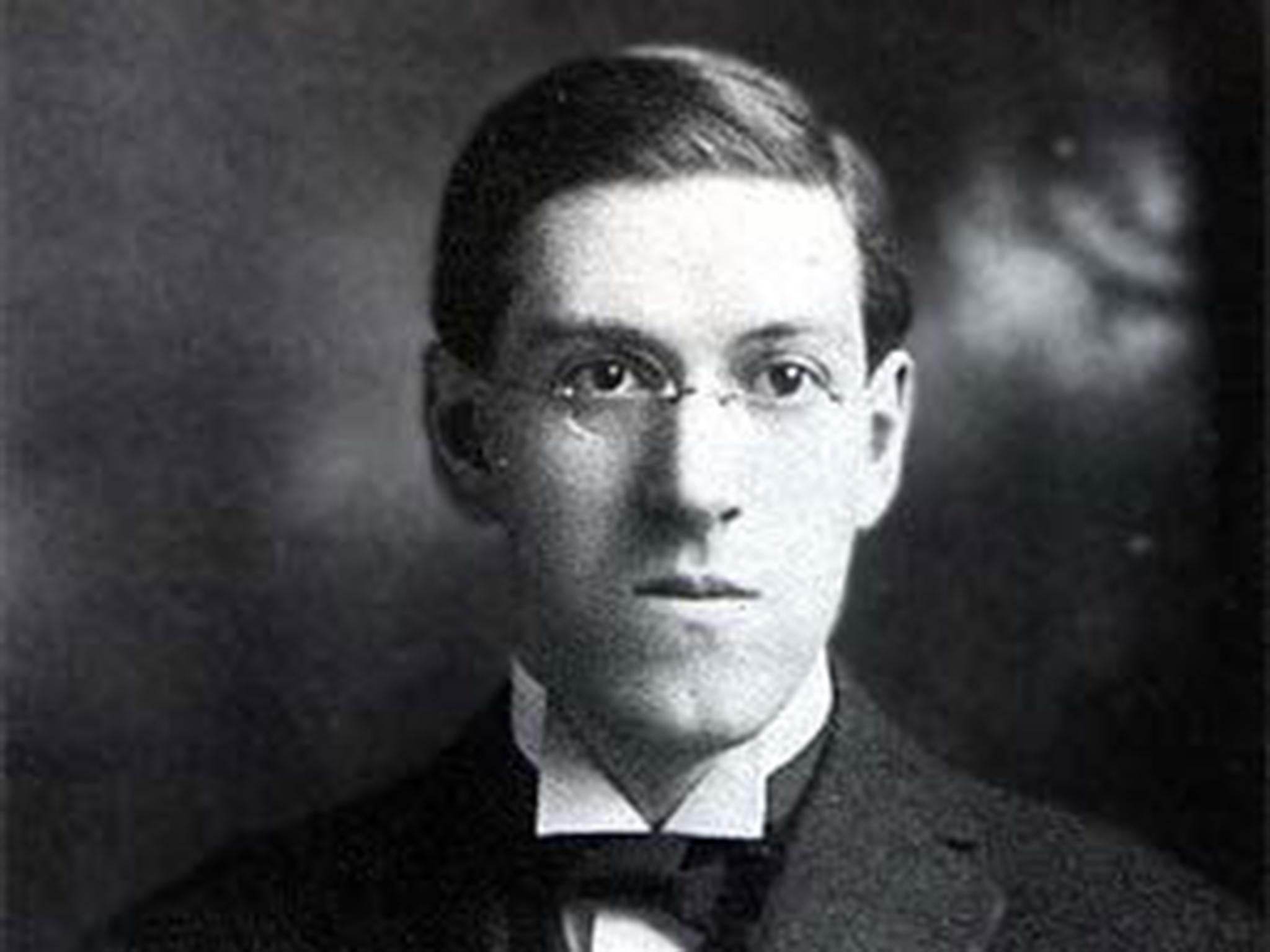

Your support makes all the difference.A century ago, a gaunt, sickly young man of 26 years sat down to write what would become the first piece of an oeuvre which would far outlive him. The short story was called The Tomb, and as opening gambits for literary immortality go, it perhaps doesn’t have the hallmarks of an instant classic. Consider the first lines:

“In relating the circumstances which have led to my confinement within this refuge for the demented, I am aware that my present position will create a natural doubt of the authenticity of my narrative. It is an unfortunate fact that the bulk of humanity is too limited in its mental vision to weigh with patience and intelligence those isolated phenomena, seen and felt only by a psychologically sensitive few, which lie outside its common experience.”

Still here? Good, because draw closed the curtains, stoke the fire, and gather around, for I have a dark tale to tell, one that indeed details the pursuit of immortality, of sorts, but which brings with it a great price… and something of a conundrum for the modern world.

That young man was Howard Phillips Lovecraft, who more often is recognised by his literary moniker, HP Lovecraft. Lovecraft was born in August 1890 and lived with his father, Winfield Scott Lovecraft, and mother, Sarah Susan Phillips, at Angell Street in Providence, which looks out on an archipelago of islands and promontories on the New England coast.

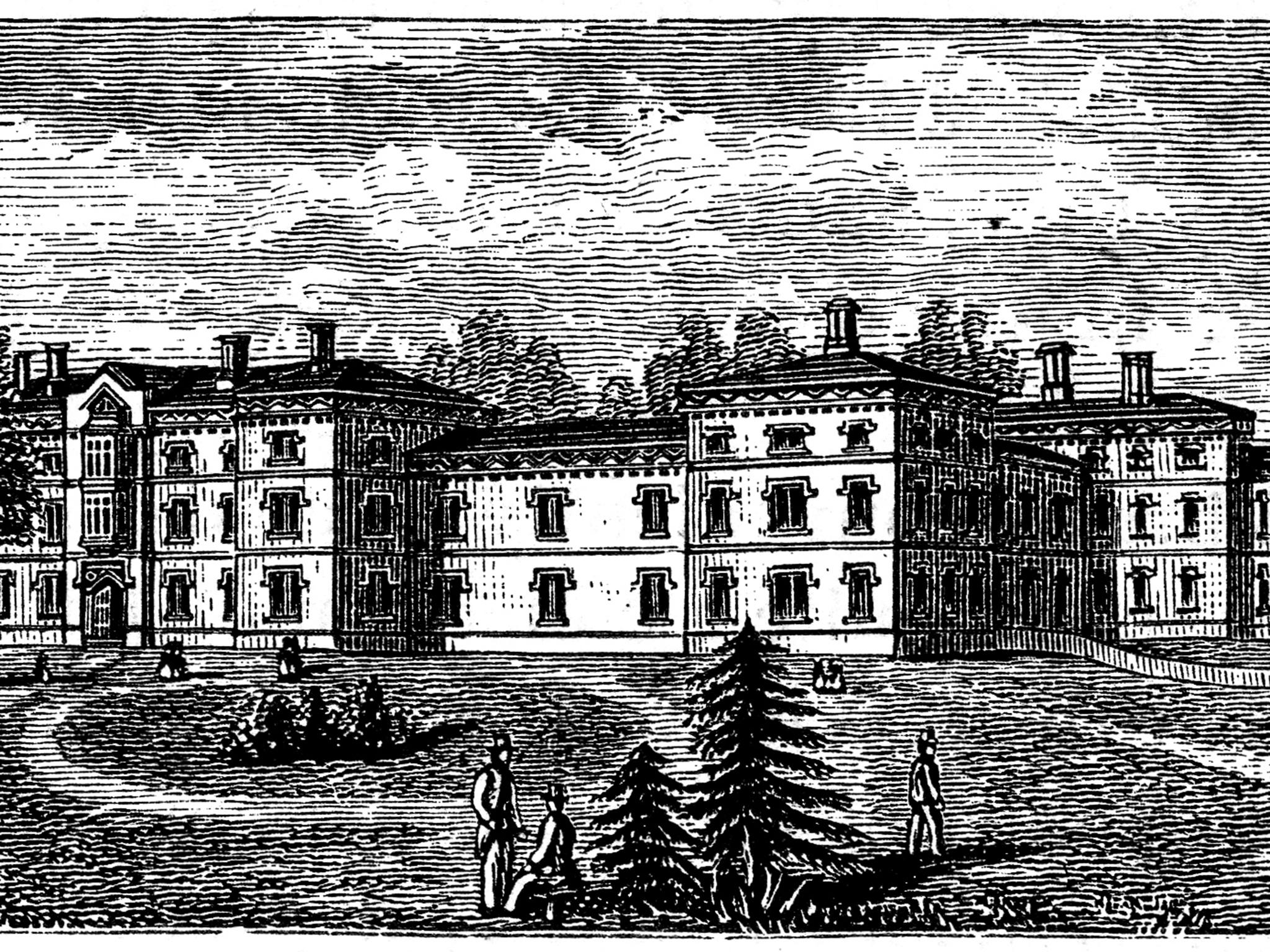

Lovecraft's father, a travelling salesman, was committed to an asylum, the Butler Hospital, with ”nervous exhaustion” when the boy was just three, and remained there until he died in 1898, leaving the youngster in the care of his mother. A nervous, sickly child, he suffered from sleep paralysis and was withdrawn from school at the age of eight, concentrating his efforts on the study of science and especially astronomy.

It was perhaps this interest in the great unknowns of the universe coupled with the fact that mental health issues were all around him – in 1919, Lovecraft’s mother, suffering hysteria and depression, was committed to the same hospital where her husband had died – that fed into Lovecraft’s literary career. While raw and verbose, The Tomb in its very first lines addressed both of those obsessions and paved the way for HP Lovecraft to become renowned as the west’s premiere exponent of weird fiction.

But it was perhaps the second story that Lovecraft wrote, in July 1917, that laid the foundations for his lasting fame. Both The Tomb, written in June, and that second story, Dagon, were written at the behest of W Paul Cook, the editor of an amateur press journal called The Vagrant, which published the first of Lovecraft’s work. Dagon introduced themes that would become synonymous with Lovecraft’s work, those of ancient, unknowable deities lurking beneath the sea, waiting to rise up and destroy the civilisation that humanity is so arrogantly confident will last for an eternity.

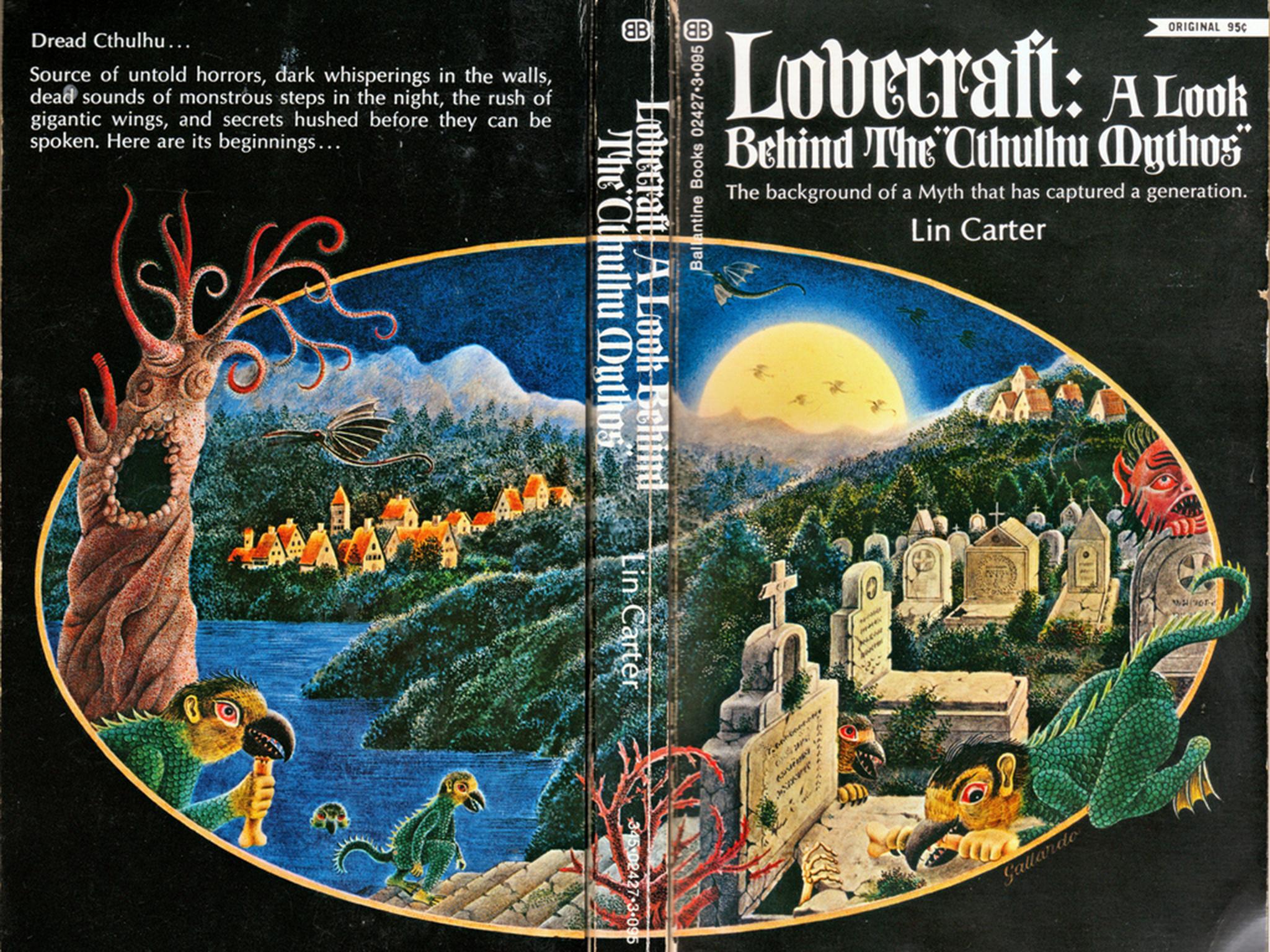

As Lovecraft attacked his writing with a ferocity that belied his sickly frame, he conjured up a whole pantheon of gods – actually cosmic alien entities of vast size and power – who wished to regain control of the Earth they once ruled before the rise of man. And the greatest of these was Cthulhu.

This water-bound entity didn’t appear until 1928’s The Call of Cthulhu, which is regarded as a classic of literature of any genre now, and Lovecraft described him thus: “…a monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers”.

His stories were a strange combination of threats so large and so apocalyptic that mankind might as well simply throw in the towel; and up-close, personal horror. The entities of the Cthulhu Mythos (as these stories became known) cannot simply rise up and destroy us; they have to inveigle their way into our lives, exert their subtle influence on cultists and the insane, gain ground in their relentless campaign inch by sinister inch.

Lovecraft died in 1937, and his stories might have died with him – he never earned a great deal from his writing while alive – but his exposure in the pulp magazines seemed to give him something of an enduring appeal. He certainly wasn’t the first to tackle such themes; Edgar Allan Poe (to whom Lovecraft surely owes a debt for his archaic writing style), Arthur Machen, Robert W Chambers (whose The King In Yellow would, decades later, influence the first series of the TV show True Detective) and Lovecraft’s contemporaries Robert E Howard (creator of Conan the Barbarian) and Clark Ashton Smith all trod similar paths.

But when the likes of Stephen King declares Lovecraft the “greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale” in the 20th century and even Joyce Carol Oates says his influence on writers of all genres who followed is “an incalculable” one, it seems that beneath his often lumpen prose, Lovecraft’s ideas were ones that were digging their claws into humanity’s souls, much like the monsters he created.

Indeed, a century on from when he sat down to write his very first story, there’s an entire industry built up around Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. Cuddly toys? By the bucketload. Cthulhu Monopoly? of course. Statues, T-shirts, role-playing games. Cthulhu even ran for president against Trump and Clinton, and is standing again in 2020 (https://cthulhuforamerica.com/).

Lovecraft’s short stories and novels are constantly in print, and his characters and themes are always being taken on by other writers.

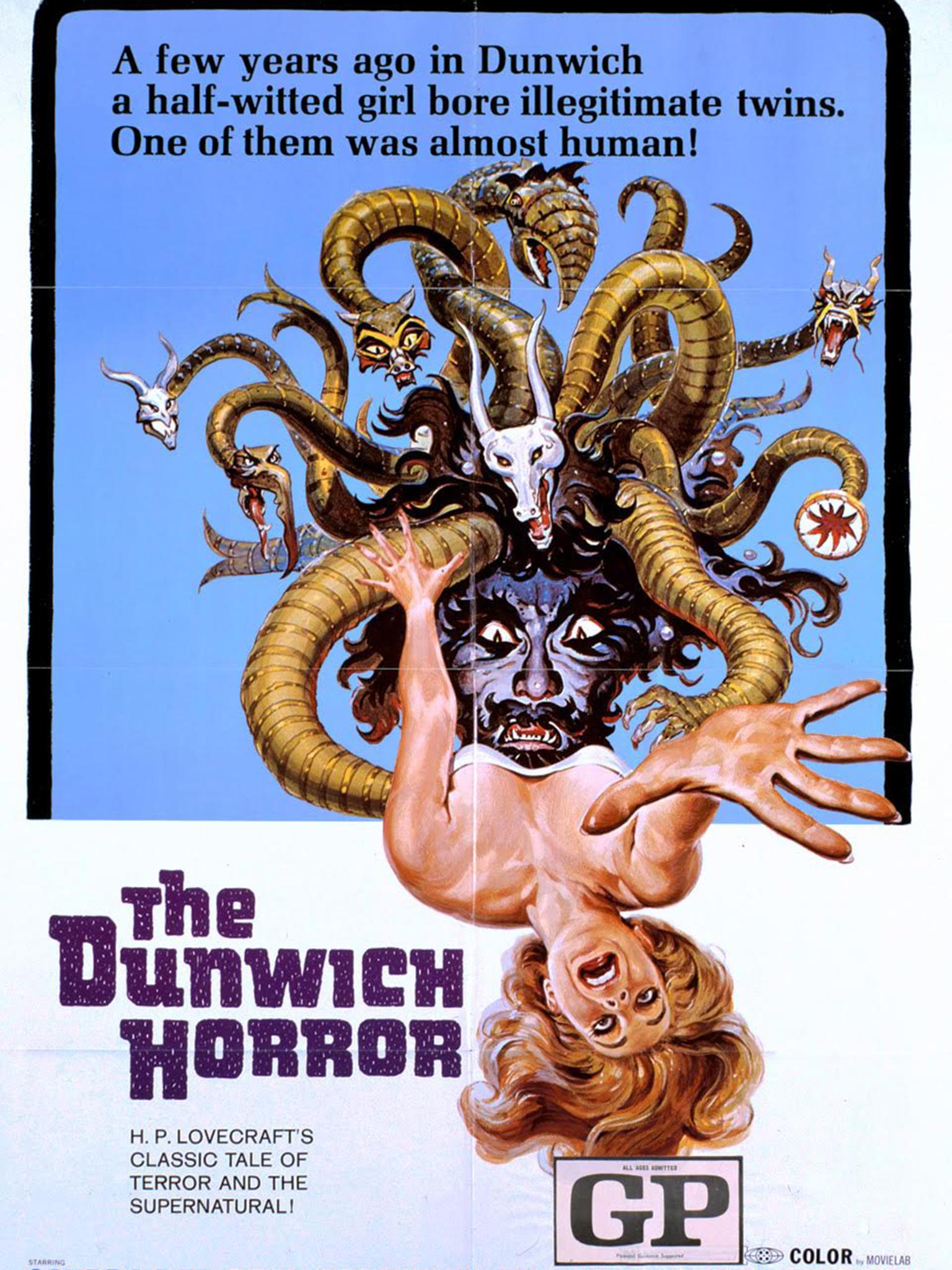

The author James Lovegrove has written a series of novels pitting Sherlock Holmes against Lovecraft’s elder gods; the paperback of the first volume, Shadwell Shadows, is out in September, closely followed in November by the hardback publication of book two, The Miskatonic Monstrosities. Lovecraft’s tales have been adapted into graphic novel form, most notably by Ian Culbard and the wife-and-husband team Leah Moore and John Reppion for the critically acclaimed British publisher Self Made Hero, and there have been various attempts to bring Lovecraft’s horrors to the big screen, perhaps most recognisably in the 1985 schlocky comedy horror Re-Animator.

However, here comes the conundrum, the dichotomy of Lovecraft’s appeal. Because while his influence on the modern horror genre is undeniable, neither is the fact that he was an out-and-out racist.

Lovecraft’s biographer, the novelist Michel Houellebecq, said that “Lovecraft's character is fascinating in part because his values were so entirely opposite to ours. He was fundamentally racist, openly reactionary, he glorified puritanical inhibitions.”

Two years ago, the organisers of the World Fantasy Award dropped their traditional prize of a bust of Lovecraft for the winner, after a campaign by authors. One of them was writer Nnedi Okorafor, who was awarded the prize in 2011 for her novel Who Fears Death. Trigger warning for racist language ahead; her delight was tempered with the discovery, thanks to a friend, of a poem Lovecraft had written in 1912 titled On The Creation of Niggers, which includes the lines, “A beast they wrought, in semi-human figure/ Filled it with vice, and called the thing a Nigger.”

Which is pretty foul stuff wherever you stand. The question that fans of the horror genre wrestle with today is how Lovecraft can be celebrated when his views were so execrable? You’ll often hear the “man of his time” argument, yet even for the early 20th century these were still extreme views, especially for someone who was raised and lived in New England and New York.

The other often-used argument is that we should be able to separate the man from the work. It is OK to appreciate Lovecraft’s stories and the impact he has had on this particular branch of literature while at the same time pushing his own views to one side?

It’s a conundrum that’s perhaps as unsolvable as any conflict in Lovecraft’s own fiction. Only one thing is certain; HP Lovecraft, and the body of work he embarked upon exactly a century ago when he wrote The Tomb, seemingly endure, though the spectre of the writer’s racism will always lurk in the background like one of the loathsome creatures of his imagination.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments