Still on the road: How hitchhiking has changed in 40 years

Amid the tangle of deadlines in modern life, hitchhiking has fallen out of fashion. Simon Calder remembers his best lifts, longest waits, favourite vehicles and the strangers’ stories that will stay with him forever

Frontiers can be particularly effective time wasters,” advises Europe: A Manual for Hitchhikers. “Traffic dwindles constantly over the last few kilometres.” I look up at the pretty Croatian hill town of Buje, just 5km from the Slovenian border, down at my watch, and along the road that runs north to the frontier. The Mercedes that has just sped past my waiting thumb is well on its way to another country.

This being 2018 rather than 1980, when the hitching manual first appeared, I then deploy my thumb to unlock my smartphone and check the boarding pass. “Venice Departs 16.10,” it warns. The plane to Gatwick is six hours and two countries away.

Amid the tangle of deadlines in modern life, hitchhiking has fallen out of fashion. But some of us are still on the road. Earlier on this sunny October morning, I could have caught the only northbound bus of the day from the town and already be halfway to Marco Polo Airport. But I chose to linger to explore Buje’s Venetian remnants, baroque church and convivial cafes. My bet: that a kind motorist would provide a lift.

Balancing the reward of a couple of hours in a Croatian hill town was the risk that I might miss the flight. The world owes no one a ride. But decades of soliciting lifts beside country roads, busy highways and autobahn service stations suggest that at least one of the motorists on Croatia’s D21 road this morning will oblige.

Hitchhiking is built on fundamentals that may seem fragile these suspicious, fractious days: that people are generous and trusting towards strangers. Evidently not the sole occupant of the shiny Mercedes that accelerated over the hill towards Slovenia, but there is probably a kind soul just around the corner.

Who he was and why he stopped, I shall never know. He is in his 50s and drives a scruffy old BMW with an overflowing ashtray (hitchers can’t afford to be fussy about the lifts they accept).

We share only a few words of German in common, and soon expend them. Which means I am free to sit and marvel at the magnificent scenery of the former Yugoslavia that he is steering through: forested foothills marching off eastwards into a haze of mountains, and vineyards unravelling towards the shimmering Adriatic in the west.

There are worse ways to travel than to be chauffeur-driven by a member of the self-selecting cohort of altruists who offer a valuable asset, in the shape of an empty car seat, to the wanderer. And expect no financial reward.

Rules of thumb

Longest wait (UK): seven hours, Kendal, Cumbria.

Longest wait (abroad): 10 hours, east of Trie, Hautes-Pyrénées, with no traffic at all for the first 9 hours.

Shortest wait: 0 seconds, east of Barèges, Hautes-Pyrénées (I was emerging from a mountain track in a rainstorm and waved a thumb across the road at a passing car, which stopped).

Shortest lift: 400 yards, around the Bay of Pierowall, Westray, Orkney.

Longest lift: 500 miles, Lincoln Nebraska to Boulder Colorado.

Scariest lift: the following day, from Glenwood Springs Colorado to a small town about 30 miles further on, with a drunk who said he was heading for Sacramento, California, but who was completely out of control.

Most famous lift-giver: comedy’s Dave Allen, in Somerset (a Range Rover).

Only female truck driver successfully hitched: in Israel. The police promptly stopped her to tick her off.

When I started hitchhiking, it was on economic grounds: at a time when a paper round was so poorly paid and the cost of transport so high, the only way to escape Crawley New Town was by thumb. Flying to or from Venice was about as likely as soaring to the moon.

Today, hitching still helps me from A, via various unpredictable locations, to B. But uniquely it provides random encounters, with the intrigue and insights they entail.

Three weeks ago, I finished lunch beside the Mediterranean in a distant corner of the Peloponnese, picked up my backpack and thumbed a ride to the nearest town that offered a bus to Athens. A couple who were shipping out at the end of the tourist season picked me up; once they found I was British, we traded tales of the uselessness of our respective governments and the absurdities and embarrassments of Brexit.

The central joy of hitching is that it puts you in instant and close contact with people whose paths would never ordinarily cross with yours. And those chance encounters should enrich both the hitcher and the driver. Thanks to the internet, you can buy a train or plane ticket and make the journey with little or no human interaction.

Granted, many people retreat into their cars expressly to avoid engaging with Jean-Paul Sartre’s arch-enemy, les autres. But plenty of folk do not share the philosopher’s view that “Hell is other people”.

Benevolent drivers may not realise it, but they are also facilitating the most efficient and least-damaging form of motorised transport on the planet. When I buy a ticket for a train, boat or plane, I add to the overall demand profile that the operator will use when planning future capacity. But hitchhiking has no such effect; the only environmental effect is the marginal amount of fuel used to carry one extra person in a vehicle (plus a minuscule amount involved in stopping to pick up and drop off the hitcher).

The social and economic benefits of increasing mobility by exploiting spare capacity have been recognised by some governments. During the Cold War, communist Poland had a Social Autostop Committee. The closest the world has had to a Ministry of Hitchhiking even had a mission statement: “Autostop facilitates seeing relics of the past, beauty of nature and modern achievements.”

From a dowdy office in Warsaw, officials issued books of coupons in various denominations – 25km, 50km and 80km – which the hitchhiker tore out and handed to the driver according to the distance travelled. The motorists collected the coupons during the year and posted them back to Warsaw in the hope of winning prizes.

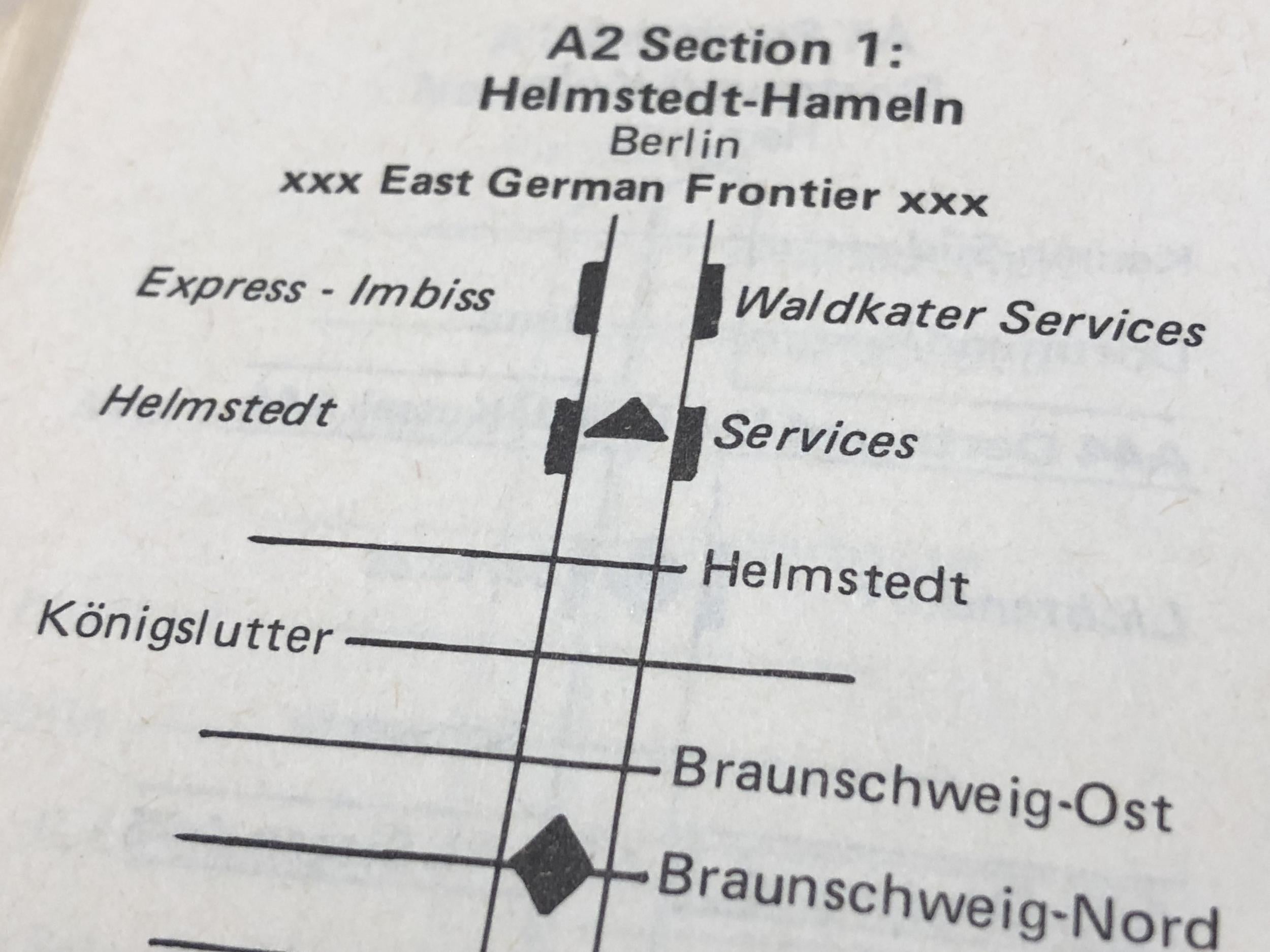

On the other side of the Berlin Wall, the easiest place in Europe from which to hitch was the Dreilinden frontier post of West Berlin. It fed the autobahn corridors to the rest of West Germany, and was also the one place in the Federal Republic where the authorities turned a blind eye to standing on the motorway.

By picking up a hitchhiker with a scrawled sign reading “München” or “Hannover”, the driver was striking a blow for liberty and making Charlies of the East German checkpoint guards.

At some border crossings in eastern Europe, hitchhiking remains mandatory because pedestrians are not allowed. When crossing from Hungary to Ukraine and from Russia to Poland, officers have ordered me to thumb a ride just ahead of the frontier post. The locals are in on the rules, and lifts are easy.

Still-communist Cuba has picked up the Polish concept of collective car-sharing but taken away both the prizes and the voluntary nature of lift-giving. Each town and city has been assigned a recognised hitching point at an important road junction – typically where the urban bypass ends and the highway to Havana begins.

The sight of 50 or more people clustered at an intersection can be disheartening, but it is surprising how many people can be squeezed into one vehicle and therefore how quickly the queue moves

The procedure is organised by officials wearing mustard-coloured trousers, nicknamed los amarillos after the Spanish word for yellow. They flag down state-owned vehicles and instruct the driver to take an appropriate number of passengers.

Some hitching points even have a waiting shelter, plus a set of re-purposed aircraft steps with which to help passengers onto the back of lorries.

“The sight of 50 or more people clustered at an intersection can be disheartening,” reports the Travellers’ Survival Kit: Cuba, “but it is surprising how many people can be squeezed into one vehicle and therefore how quickly the queue moves”.

The concepts of “moving quickly” and “hitchhiking” have little overlap. I shudder at the amount of my life that I have squandered beside dismal roundabouts from Doncaster to Dortmund.

There is also an observable correlation between the propensity of a motorist to pick up hitchhikers and the age of their vehicle. Conversely, the newer and more reliable a car, the less likely the driver is to stop.

Accordingly, the average lift is disproportionately likely to break down. One Saturday, I was thumbing from London to Bristol to give a talk on hitchhiking, but had to phone from the hard shoulder outside Swindon to confess I would be late due to the failure of the alternator in the elderly beige Ford Sierra in which I was travelling.

Embarrassment is the least of the hitchhiker’s worries. Many female hitchhikers report sexual harassment from drivers who have picked them up, and there have been some horrific cases of rape or murder by motorists who prey on hitchers. Statistically, accidental death is a much more likely fate for the hitchhiker – a reflection of the awful body count on the roads worldwide. An average of 2,425 people a day die in road accidents, and some of the victims are hitchhikers. I have been fortunate, with only one night in hospital. So far…

Rules of thumb

Fastest vehicle: Alfa Romeo, Brighton to Crawley, peaking at 125mph.

Most impressive vehicle: Mercedes CLK 209 driven by a test driver from rival firm Porsche through the Black Forest in Germany.

Least impressive vehicle: a tie between a Turkish refuse truck (standing on the rail on the back) and a JCB in Greece (I was in the bucket).

Most challenging lift: a Mercedes estate which was completely full but whose driver invited me to stand on the rear bumper and hang on to the trim. It worked.

Favourite hitching spot (for quick lifts): Chiswick flyover, M4 west.

Favourite hitching spot (for scenery): the road around Lake Ohrid, southwest Macedonia/eastern Albania.

Least favourite hitching spot (UK): any of the tricky junctions on the Edinburgh bypass, especially the A7.

Least favourite hitching spot (abroad): Vienna, on the A4 junction at Simmering, heading east (and yes, all the other possibilities nearby are rubbish too; I checked).

From the driver’s perspective, too, there are risks. The man in the BMW was betting that I was neither an axe murderer nor, as a border crossing was involved, a drug smuggler. The frontier between Croatia and Slovenia might be intra-EU, but it is a proper Brexiteer’s border, with lots of uniformed officials and forensic inspection of passports. The checkpoint official was confident we posed no threat and waved us away, past the salt flats which constitute Slovenia’s southwestern flank and are rich in bird life of many species.

As a species, lift-givers have some predominant characteristics. Single males provide more than half the lifts I get. One reason: they represent overwhelmingly the leading demographic for lorry and van drivers.

Relative to their numbers on the roads, non-white drivers prove more generous than their white counterparts. Couples, usually heterosexual, are next, with families low down the list due to practicalities. Mum, dad and two kids leave little room for guests in the form of hitchhikers. Single females rarely stop (at least for me).

Countless hours by the roadside have given me plenty of time to contemplate why people stop, and why they don’t. The negatives are easier to assess than the positives: perception of danger is probably the strongest, but there is also the discomforting thought that the hitcher will turn out to be smelly, boring or mentally disturbed – after all, who in their right mind hitches today?

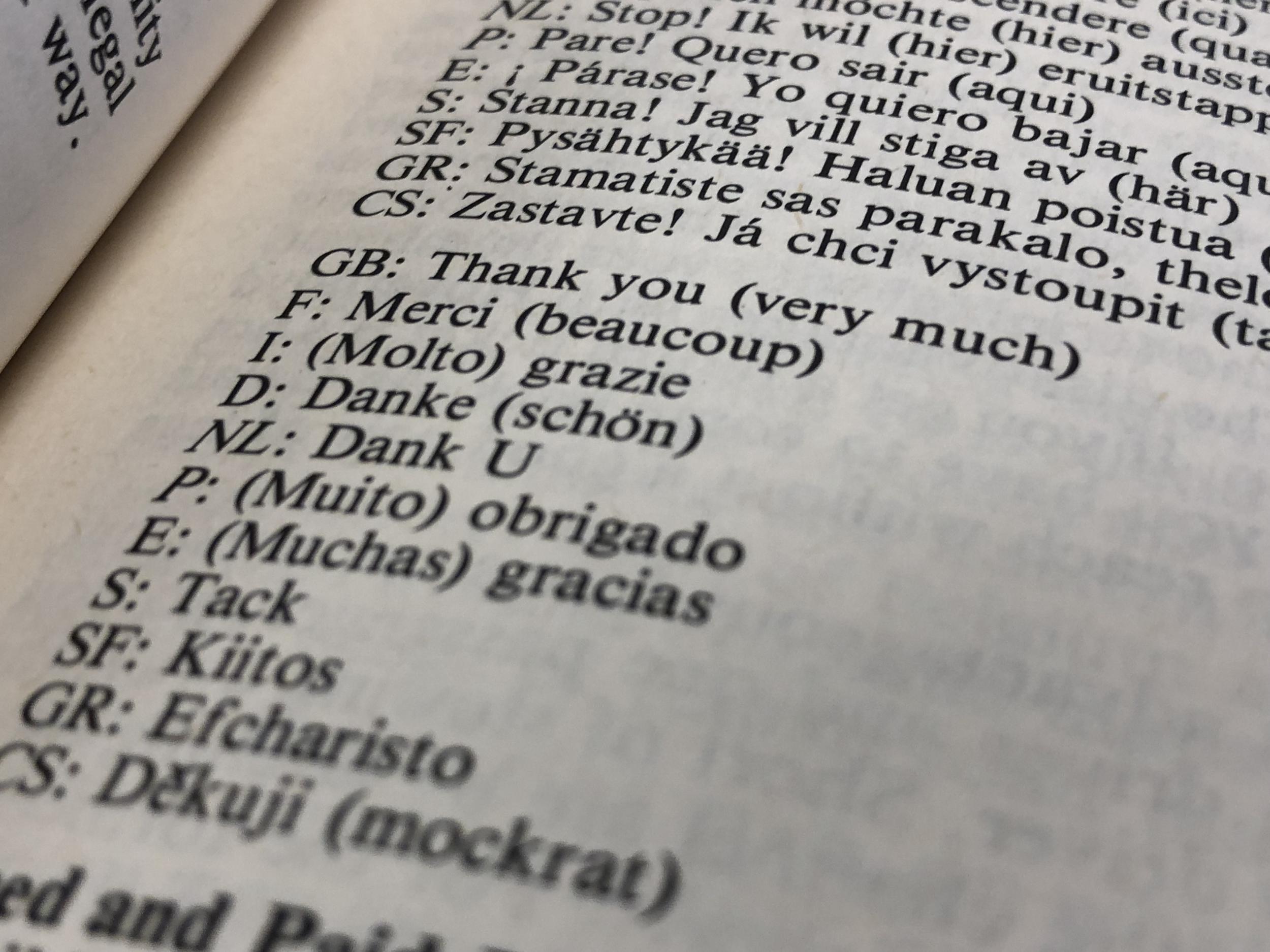

Yet helping strangers is a basic human motivation, and that explains why some people still stop. By giving a lift, the donor gets a lift – the psychological reward of providing help to a grateful recipient. (Europe: A Manual for Hitchhikers provides translations of “Thank you very much” in French, Italian, German and seven other languages.)

On occasion, the hitchhiker can provide deeper emotional support, as a non-judgmental stranger who will listen to the longings of people who yearn to be heard.

I know there is a middle-aged man in Bristol who carries deep sadness about his broken relationship with his brother, and a woman in Oregon who was so desperate to talk about the hand that life has dealt her that she skipped a dentist’s appointment 20 miles up the road and continued for 200 miles as she untangled her complications and disappointments. I hope I helped to provide them with some comfort, as they did for me.

If hitching is so great, then, why do you see so few people thumbing these days? Mainly because of the remarkable low-cost transport revolution that began towards the end of the 20th century.

First airlines, then railways, realised that there was a vast, unserved market of people who would travel if the price was right. While InterRail (a concept regarded with disdain by hitching purists) had showed the virtue of filling empty seats on European trains with backpackers as early as 1972, it took the no-frills airlines to persuade transport providers of the benefits of demand-based pricing.

When I started working, a return ticket from London to Manchester by train used to cost a week’s wages. It still can, if you choose a £338 Anytime return. But plan a week in advance and travel off-peak, and the fare falls to £54 (or one-third less with a railcard). Still too much? Megabus is waiting at £14 return. That is scarcely more than than a Tube fare out to Brent Cross and back, still the traditional start for a journey up the M1.

Europe: A Manual for Hitchhikers made it to a second edition in 1985, but no further. On Amazon right now there’s a copy available for 79p, which rather sums up the low value placed on thumbing by contemporary travellers.

Perhaps the driver who was speeding me through Slovenia towards Trieste in Italy was was part of the late 20th century hitchhiking generation, and is still reciprocating the kindness of strangers in an era when, to quote the manual on Yugoslavia: “A lift in anything under an hour is fairly close to a miracle.”

The supply of drivers who were inveterate hitchhikers and are giving back is dwindling. The move in the western world away from car ownership and towards asset-sharing will benefit the environment but not the hitcher. And I imagine that a lift-giving algorithm is not top of the list for developers of autonomous cars.

Before hitching reaches extinction, reach for that road map and take your chances with humanity. Stop seeking certainty, and start cherishing uncertainty. As transport is becoming increasingly transactional, hitchhiking makes travel emotional again.

Simon Calder is travel correspondent at The Independent and author of ‘Europe: A Manual for Hitchhikers’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments