Inside the world of limb-lengthening surgery

Leg-lengthening surgery has become an increasingly popular option for the height conscious. Sean T Smith speaks to patients finding their feet after a painful and costly process

Each year, increasing numbers of people, particularly young men, are opting to have their legs surgically broken and then gradually extended so that they can gain a few precious inches of extra height.

Oliver* explains how the decision to travel to Istanbul for limb-lengthening surgery came about over time. “I always felt quite insecure about my height I’d had therapy sessions about it before but they never really helped,” he tells me. “Then I came across other people getting this surgery on Instagram and was reading about how it affected their confidence positively. I decided it was worth the pain and money to get rid of this insecurity once and for all.”

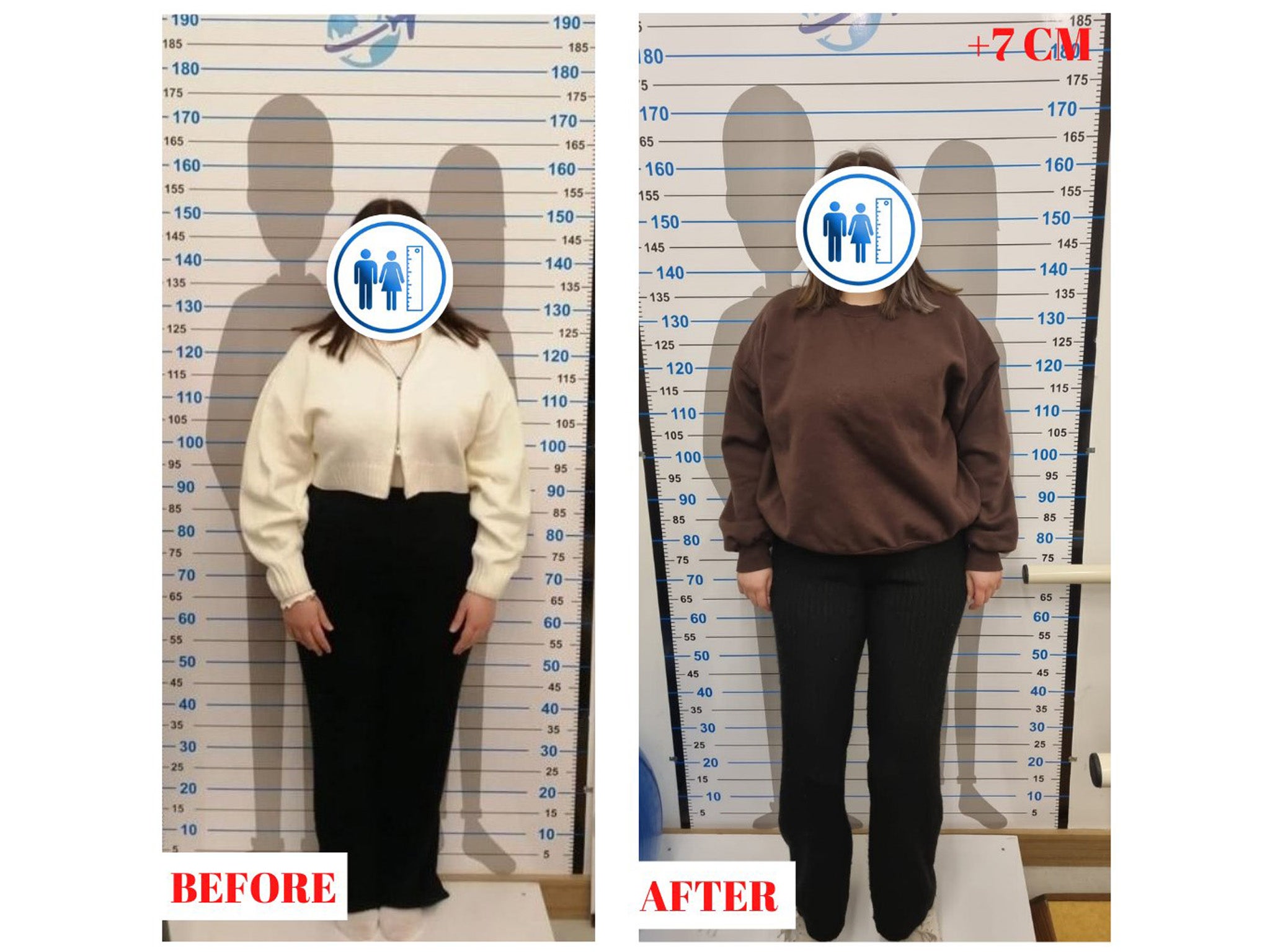

Combining income from casual work as a freelance writer and waiter, Oliver managed to save enough money for the surgery that would boost his height from 5ft 6in up to the psychologically important male average milestone of 5ft 9in.

Now back home in the UK, Oliver is only just finding his feet. “The recovery time isn’t quick,” he tells me. “It’s taken about five months to start walking normally again.”

Turkey has long been a popular destination for medical tourists and now ranks among the top 10 countries for popular treatments like dental implants, tummy tucks, breast augmentation, and rhinoplasty.

But limb lengthening is not just another cosmetic procedure. It is a moderate to high-risk surgery where post-operative care really matters. Unless patients are prepared to submit to intensive physiotherapy for the lengthening period of around 80 days they run the risk of potentially life-changing complications.

Wanna Be Taller is an Istanbul clinic that has helped 450 patients become taller in the last seven years. Its website promises “a beautiful experience from the moment you arrive in Istanbul until the time you achieve your desired height.”

As a patient welfare coordinator, Jana is responsible for liaising with patients and maintaining their wellbeing from their first initial enquiries until well after they’ve returned home to resume their normal lives.

She is effervescent and kind and it’s easy to see whys so many patients confide in her. Of diminutive stature herself, she says she understands what drives patients into taking what might seem such a drastic decision.

“I definitely sympathise. In this job you can’t have judgement,” Jana tells me. “Patients come from all over the world but mostly from America and China. They come here because we offer affordable prices compared to the United States where [limb lengthening surgery] is very expensive and doesn’t include the cost of post-operative care.”

After the surgery, patients are typically hospitalised for five days. Then the clinic’s patients are checked into a hotel in Istanbul for post-operative care where they receive visits from the clinics’ caregivers between 10am and 6pm.

“Most patients tend to stay here for three or four months before returning back to their country,” says Jana.

Any attempt to hasten or cut short that crucial physiotherapy period often ends badly. “In the past patients have stayed for just a month before returning home but most faced with complications like infections and muscle contractions,” she says.

The risks of limb lengthening surgery are not to be taken lightly. Medical complications can include deep vein thrombosis and fat embolism. In rare cases, the bone might fail to knit properly and bone graft surgery might be needed.

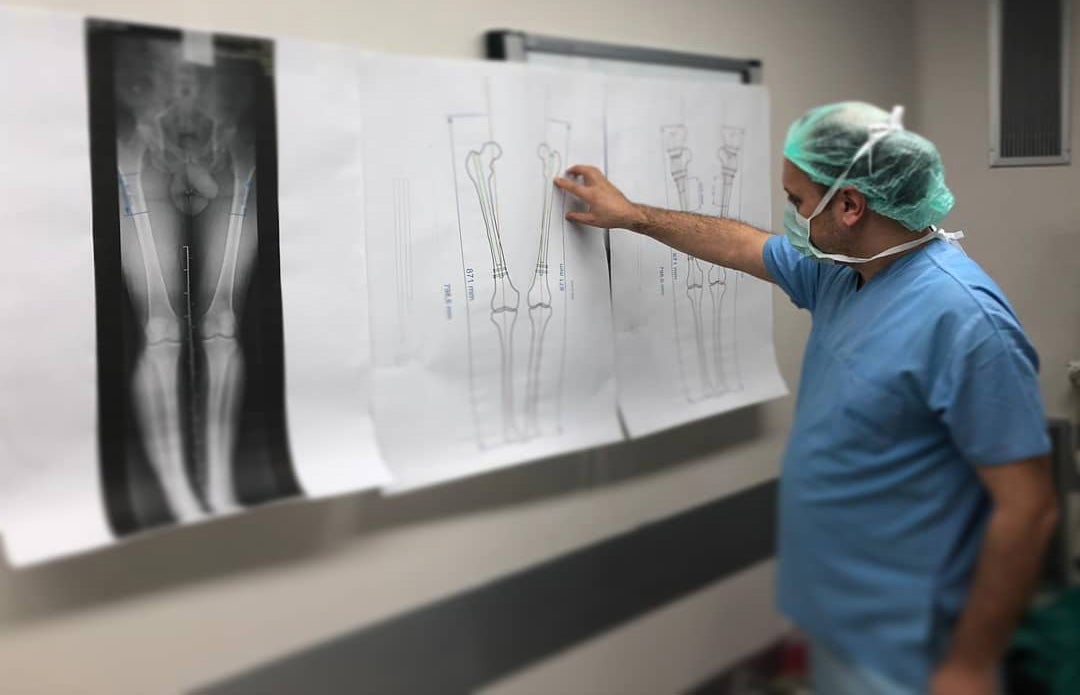

Jan explains that most patients are male adults typically between 25 and 45. They tend to be around 1.62m and are looking to extend their height by 8cm by having their femurs (thigh bones) fractured and then lengthened.

However, as much as 14cm of growth is possible for patients who are prepared to undergo a second round of painful surgery on their lower limbs (tibia) a year or so later.

But according to Jana, most patients have more modest goals. She explains that many patients simply want to surpass their girlfriend’s height. Having greater confidence at work is also one given as one of the reasons young men are prepared to undergo the painful procedure.

The body responds by producing new bone to bridge the gap and so over a period of approximately 80 days, the hairline fracture grows into a bridged fissure of new bone

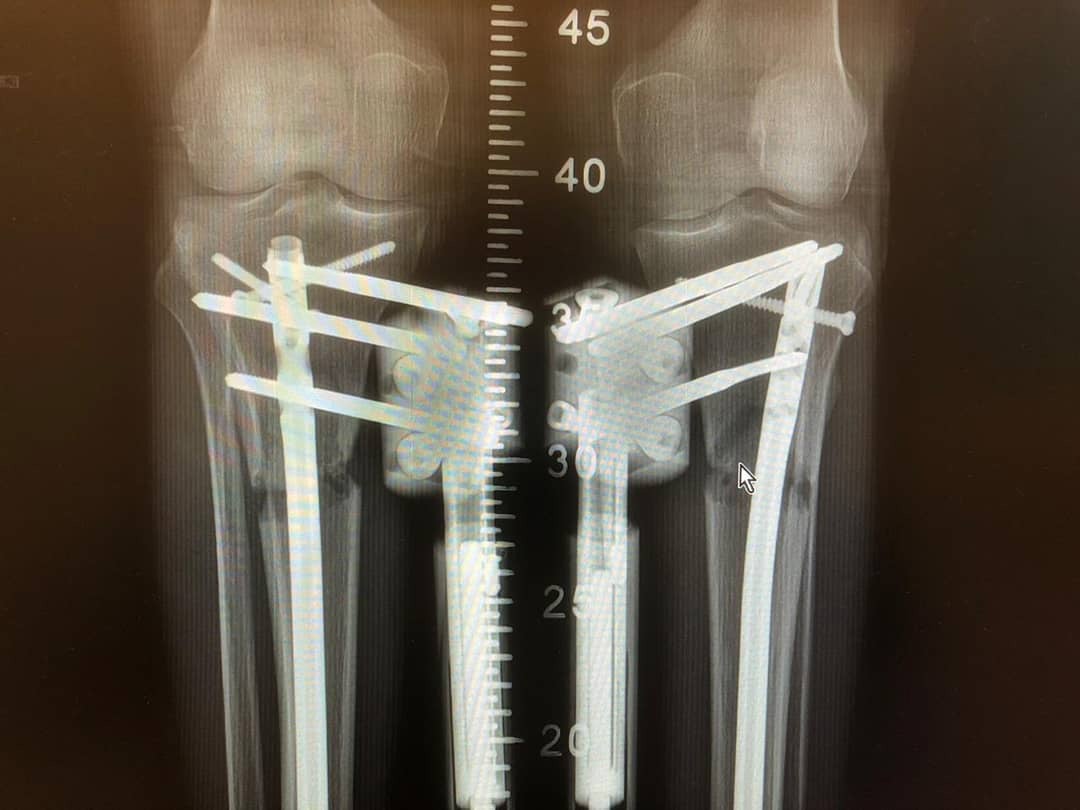

There are several techniques that can be used to lengthen limbs. Jana outlines the “Precice” method first. After drilling into the femur (thigh bone), the surgeon fractures it cleanly with a hammer and chisel.

This creates a channel in the thigh bone where an internal lengthening nail is implanted and secured with screws that are drilled in above and below the fracture. The screws are just below the hip and above the knee. After surgery, magnetic sensors are operated by remote control to extend the nail at a rate of around 1mm a day.

The body responds by producing new bone to bridge the gap and so over a period of approximately 80 days, the hairline fracture grows into a bridged fissure of new bone typically of 2 to 3 inches in length. But the precice method with post-operative care costs $40,000 and is prohibitively expensive for many.

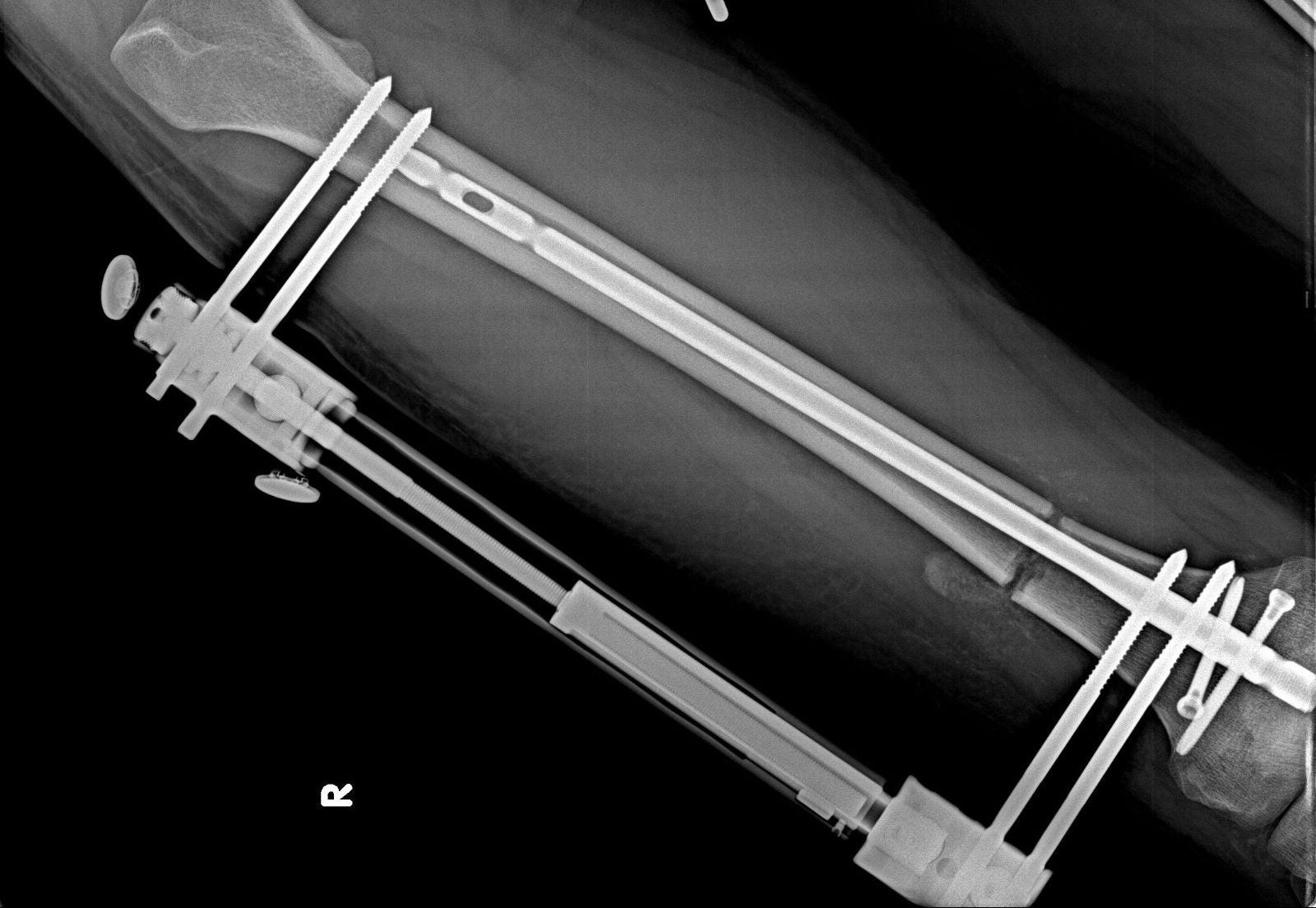

For younger patients in their twenties who typically tend to have more limited resources, Wanna Be Taller continues to offer the far cheaper “Lengthening Over Nail” method of limb lengthening – costing $23,850. The LON method is a modernised version of the original limb lengthening technique pioneered by Russian physician, Gavriil Ilizarov in the 1950s to help soldiers recover from battlefield injuries.

The LON method still uses an Ilizarov – a sort of external fixator or metal frame that is wrapped around the leg externally and attached to the bone through the skin with pins. A gradual elongation of the external frame promotes the body’s formation of new bridging bone.

“It’s painful unfortunately and involves a bulky object being attached to your leg for two or three months – the lengthening is performed with a metal alloy key, inserted into the hole and [manually] turned 90 degrees every six hours four times a day resulting in a growth rate of around 1mm per day,” explains Jana.

The LON method is not for the squeamish. When Jana demonstrates the manual turning mechanism to me I flinch involuntarily, imagining how excruciating the pain must be. As well as being more painful, the LON method is likely to result in scarring on the legs and poses a greater infection risk which has to be carefully managed.

“After surgery, the first few days are pretty rough, to be honest,” Jana tells me. “While some patients can take the pain quite easily, most require a mixture of strong painkillers and morphine in conjunction with antibiotics and blood thinners. The patients are usually hospitalised for five days. Once they’re discharged to the hotel, the medications are received orally.”

The follow-up care given at the hotel is vital. As well as the intensive daily physiotherapy and stretching exercises, Jana explains that the patient requires X-rays every fortnight to ensure that the bones are not being pulled apart at a faster rate than the new bone is forming.

Like many of the younger patients, Oliver opted for the more cost-effective LON method of limb lengthening. Although at times, it can be excruciating, for Oliver the pain wasn’t the worst part of his limb lengthening procedure.

“The most difficult aspect was probably the boredom of laying in bed most of the day during the lengthening as you can’t walk without [assistance] for the first 3 months,” he says.

Jana attempts to keep in touch with patients long after they’ve returned to their home countries to resume normal lives and is still in regular contact with Oliver but quite a few patients tend to lose touch quite quickly. Over time she notices that it takes longer for them to respond to her texts and she thinks that many prefer to leave the experience behind them and keep it private.

She explains that patients often conceal the true nature of their procedure from even the closest members of their social circle. She was recently asked to become complicit in an elaborate cover story where one patient asked her to help convince a visiting family member that he was in Istanbul for essential surgery to correct a limb deformity.

Others have returned home making light of their suddenly enhanced stature explaining it away as a result of stretching exercises or a height growth pill. One apparently even told his parents that his increased height was a side effect of eating Turkish food.

But given that it typically takes eight or nine months to make a full recovery, most patients confide in their family and their close social circle because they need their support. Jana explains that problems in forming and maintaining romantic relationships can be key motivators for young men. She recounts the heart-breaking experience of another young patient who she befriended recently. He was jilted just before his wedding because one of the bride’s friends had raised concerns about the stature of their future children.

But Jana thinks that the desire to be more confident in the workplace is an even more powerful factor in young men seeking a surgical solution.

Some speak of not being taken seriously or of having their ideas brushed aside in the workplace. Many have felt obliged to laugh along with jokes at their lack of height while feeling the pain of the humiliation very keenly. For some, the long-term cumulative effect is corrosive and can lead to anxiety depression and a constant sense of low self-esteem.

A research report published in the American Journal of Psychiatry found a highly suggestive inverse association between height and suicide rates.

There seems to be an implicit, unstated sense that when short people do achieve high-status positions they’re still deemed to lack the ‘natural authority’ to wield real power

In her compelling 2017 book Shortchanged: Height Discrimination and Strategies for Social Change, Tanya S Osensky argues that heightism is the last socially acceptable form of discrimination. According to Osensky, heightism hides in plain sight because it’s such an insidious unconscious bias that’s “so casually expressed we don’t even realise we are doing it.”

Osensky makes the comparison with racial and sexual discrimination: although social norms dictate that comments about an individual’s physical traits are unacceptable for some reason we generally do not make that connection when it comes to height.

She points out that although the kind of racist or sexist “banter” that was common in the workplace 40 years ago, would horrify us today it’s perfectly acceptable for us to be drawn into a discussion grumbling about a diminutive manager’s Napoleon syndrome, for example.

There seems to be an implicit, unstated sense that when short people do achieve high-status positions they’re still deemed to lack the “natural authority” to wield real power. We’re way passed criticising a political leader’s ethnic origin but satirical cartoons invariably draw attention to Rishi Sunak’s lack of stature, for example.

The term “heightism” was coined by Saul Feldman in 1971. The generations of sociologists who have followed have theorised that heightism has an evolutionary origin. In a world where we have evolved to associate height with strength and power, it’s easy to see how size might become unconsciously conflated with social standing and credibility in the workplace.

Workplace statistics would seem to bear this out. Studies from the UK, China and the US all show a correlation between greater height and greater pay while separate research has suggested just 3 per cent of CEOs were below 5ft 7in. Another study found that CEOs were on average 3in taller than the general population.

And if it’s tempting to reach for the “woke” word at the prospect of another work-based “ism” to worry about, perhaps we should pause to consider the possibility that we might be displaying the classic signs of what Osensky calls “tall privilege”.

The hallmark of true privilege is being blissfully unaware of all the advantages you’ve effortlessly accrued without even realising it while simultaneously having no understanding of the indignities your less fortunate peers routinely have to put up with.

Back home in the UK, five months on from his surgery, Oliver is approximately two-thirds of the way through the recovery process and his mobility is only just beginning to get back to normal. But, crucially, he has achieved his target height – the UK average of 5ft 9in.

“I’m a lot more confident and happy with my image now,” he says. “I’ve started weightlifting at the gym and people have commented very positively about my new height which feels great.”

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the insidiously pernicious force of heightism must be alive and well in our society for increasing numbers of people, and especially young men, to run the risk of excruciating pain and life-changing complications just to stand that little bit taller.

The scale of that risk is hard to quantify because the medical tourism industry is not internationally regulated so there is little data on post-procedure complications.

For his part, Oliver insists that height surgery is not to be taken lightly and should only be considered as a last resort

“My advice to people considering it would be to try to exhaust other options about your self-image first,” he says. “Perhaps there are other things you can address to enhance your confidence and self-esteem. But, if your height seems to be the main factor then be prepared to spend a decent amount of money and tolerate a fair amount of pain.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments