Harambe one year on: How the gorilla became an internet meme

A split-second decision, to shoot an animal and save a child’s life, became one of 2016’s most talked-about memes. David Barnett asks what it was about the incident that the internet became so obsessed about

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A year ago today a gorilla died… and an internet phenomenon was born.

You’ll have heard of Harambe, of course. He was a 17-year-old Western lowland gorilla, resident at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens since 2014, to where he had been transferred from a zoo in Texas where he was born in captivity.

Harambe might have meant nothing save to the thousands of people who passed through the zoo’s gates to see him but for the incident on 28 May 2016 when a three-year-old boy climbed into the gorilla enclosure and fell into the moat separating the primates’ territory from the human visitors.

Harambe grabbed the boy from the moat. A zoo worker, fearing for the child’s life, shot and killed the gorilla. A zoo attraction became a news story. And then, perhaps inexplicably, so much more.

Within hours of the incident there was a lot of discussion about animals in captivity, debate about the rights and wrongs of killing Harambe, and an outpouring of grief on social media about the death of an animal. All that’s understandable.

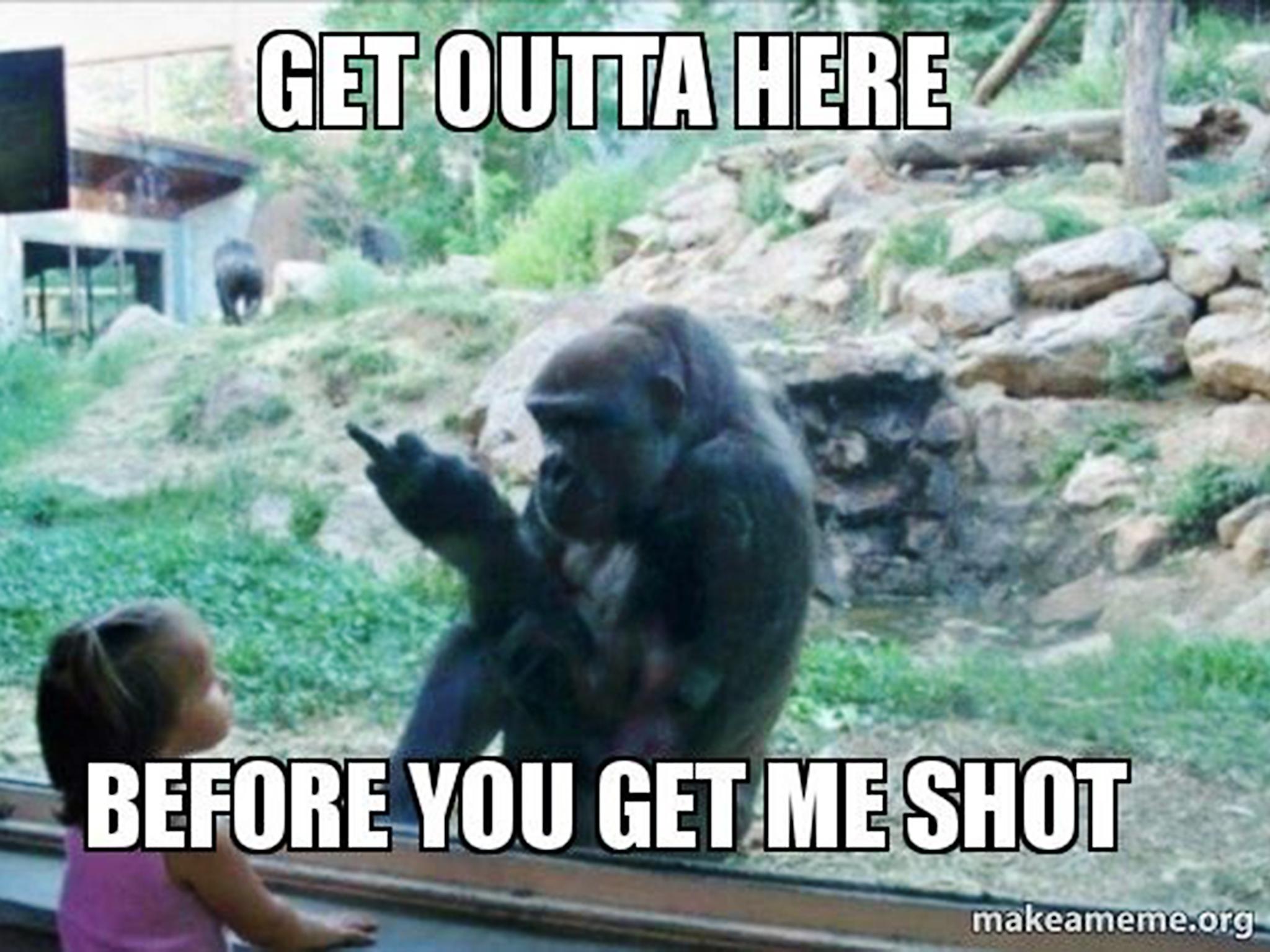

But the grief swiftly became something else. People began to employ the name and image of Harambe in quite unexpected ways. There were jokes. There were Photoshopped pictures of Harambe with celebrities. He appeared on election ballot papers. Harambe had become a message, an entity divorced from the reality of the gorilla, a thing that existed and evolved and grew on the internet. He had become a meme.

Why Harambe? Why not the two lions who were shot at a zoo in Santiago, Chile, when a man climbed into their enclosure less than a week before the Harambe incident? Just what is a meme, and what makes one go crazily viral like Harambe?

It might be surprising to know that there is actually science behind this, and has been for a long time – for more than 30 years, predating the ubiquity of the internet and social media by a long way. It’s known as memetics.

“Memetic theory, or memetics, is a scientific field invented in 1976 [the term was coined by Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene] and related to how information evolves and is replicated in human culture and society,” says Shontavia Johnson. “Each unit of information, called a meme, undergoes a process of ‘natural selection’ comparable to that of genetic evolution. When one person imitates another person, the meme is passed to the new person, who probably will continue to pass it on to another. And so on and so on.”

Johnson is Professor of Law and Kern Family Chair in Intellectual Property Law at Drake University Law School in Des Moines, Iowa, and has made a study of memetic theory and how it applies to the proliferation of social media in the modern age.

She says: “Today, the internet meme [what most people now just call a meme] is a piece of media that is copied and quickly spread online. One of the first uses of the internet meme idea arose in 1994, when Mike Godwin, an American attorney and internet law expert, used the word ‘meme’ to characterise the rapid spread of ideas online.”

We saw another example of the meme just this week in the wake of the horrific Manchester suicide bombing that claimed 22 lives at the Ariana Grande concert on Monday night. After the shock, the outrage, the heartbreak, came on Twitter the hashtag #BritishThreatLevels, in response to the UK Government raising the security status in the wake of the bombing to “critical”. Twitter users posted their own ideas of typically British ideas of “threat”… making eye contact with strangers on the Tube, that sort of thing. But the incidents that spark these memes, from the savage murder of children in Manchester to the shooting of a gorilla, are far from funny. So why do humorous memes rise from them?

“Because we live in a world that is always connected and always online, tragedies that dominate headlines also dominate social media trends and discussions,” says Johnson. “These kinds of events are important to us, perhaps because we’ve been to pop concerts or have an affinity for certain wildlife, and naturally as more people, who are used to communicating through hashtags and memes, talk about these tragedies, they will use communication methods most familiar to them. We want to be connected to other humans in times of crisis – memes and hashtags allow us to express a level of familiarity with many other people instantly.”

While #BritishThreatLevels can be seen as a slightly-skewed stiff-upper-lip “we will not be cowed” response to terrorism, the Harambe memes were somewhat more off-kilter, and took a somewhat disturbing path. White supremacists and alt-right keyboard warriors began to twist the Harambe memes into blatantly racist postings, essentially comparing apes to black people.

But was it disrespectful from the start – to a dead animal, to a child who perhaps almost died – or was it some kind of coping mechanism for people trying to make sense of it?

Johnson says, “I think it could be both. With Harambe’s killing, for example, the memes quickly went from tributes and mourning to something more sinister, with racist undertones. In other instances, I think it can certainly be used to quickly connect with others who are also feeling disturbed, vulnerable, or frightened. It really depends on the community. Different communities relate to each other in different ways – some by ostracising others, and some by supporting others.”

It isn’t just the people who create the memes – pictures of Harambe in the afterlife with 2016’s other notable dead celebrities, such as David Bowie, Harambe climbing the Empire State building, Kong-like, Mohammed Ali towering over a knocked-out Harambe – but the millions of people who share them around. If Harambe was a product or commodity, he’d have more market share than Coke or Mickey Mouse.

Matt Smith is a director of London-based company The Viral Factory, which creates videos for clients with something to sell and attempts to make get them shared around the internet. They make ads, basically, but the people they work for don’t want a traditional TV ad for a variety of reasons – budget, it’s a niche product or service, or their target audience is largely online rather than conventional TV consumers.

Perhaps Smith – or his clients, rather – would like to be able to bottle the elusive something that memes like Harambe have, but he knows it’s not so simple.

“When you’re putting together a viral marketing campaign there’s absolutely no point trying to factor in something like the Harambe situation because it’s just so random,” he says. “The internet has become really commoditised but memes feel like something from back in the early days of the internet… they’re by the people, and if companies try to co-opt them or replicate them then it can backfire badly.”

Smith cites an example in Italy where drivers stuck in a huge traffic jam were given free ice cream by a small local company. The event got massively shared around the internet, but because it was spontaneous and, crucially, non-corporate. Because it was a tiny artisanal ice cream maker it had meme legs; if it had been a giant international conglomerate rocking up with trucks of ice lollies and their branding everywhere, it would just have been a publicity stunt.

“Things like Harambe and #BritishThreatLevels work because they have a massive emotional resonance. It’s a visceral response to something dreadful, and often people deal with things like this through humour.”

But what makes a good meme? Say I post a video of my cat chasing a butterfly on Twitter today and it gets half a dozen likes. You might tweet a similar thing tomorrow, and it goes viral. Is it luck? timing? The fact you have more followers than me?

“Probably all of the above, though perhaps there’s something to be learned from memetic theory,” says Johnson. She points out that there are three “good tricks” which researchers point to in a meme’s success: being genuinely useful to a human host; being easily imitated by human brains; and answering questions that the human brain finds of interest.

For a perfect example, Johnson points to the Ice Bucket Challenge meme of the summer of 2014, which essentially involved people dumping buckets of ice water over their own heads and posting the videos online. But this wasn’t just internet daftness.

“It was not only easy to copy, but also publicly obligated people to do something useful – donate to the ALS Association (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) in the US or the Motor Neurone Disease Association in the UK. In addition, that money was used to help find a cure for ALS disease – answering questions that humans want answered.”

One year on, you might not even have thought about Harambe but for this article. Memes have limited lifespans, but just how long they thrive for is basically down to survival of the fittest.

“When Dawkins created the theory of memetics, he borrowed heavily from principles of Darwinian evolution,” says Johnson. “Dawkins and other scientists have suggested that memes compete, reproduce and evolve just as genes do.”

Despite the science behind it, we don’t know what the next big meme will be until it hits us. But you can rest assured, whatever it is, it’s on its way… and there’s a very good chance it might be born out of tragedy.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments