Ghostwatch: The 1992 paranormal investigation that just had to be true, because it was on the BBC

A quarter of a century ago, the BBC made television history – and received record levels of complaints – with its ‘Ghostwatch’ programme on Halloween. The memory of it still gives David Barnett the shivers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Halloween night, 1992. It was a Saturday, and I was somewhere near Weston-super-Mare, I think, in a quiet, out-of-season bed and breakfast. I was 22; there was some event on the Sunday I had to be up early for; I can’t remember what now. But I do remember sitting in a small room that wasn’t my own, far from home, not sure what to do with myself. So I watched Ghostwatch.

Halloween wasn’t the big deal then that it is today. A smattering of small children half-heartedly trick or treating; maybe a fancy dress party somewhere, if you were lucky a nice, classic horror film on TV very late on. So Ghostwatch piqued the interest; it was a live television event of the sort we didn’t get very often back then.

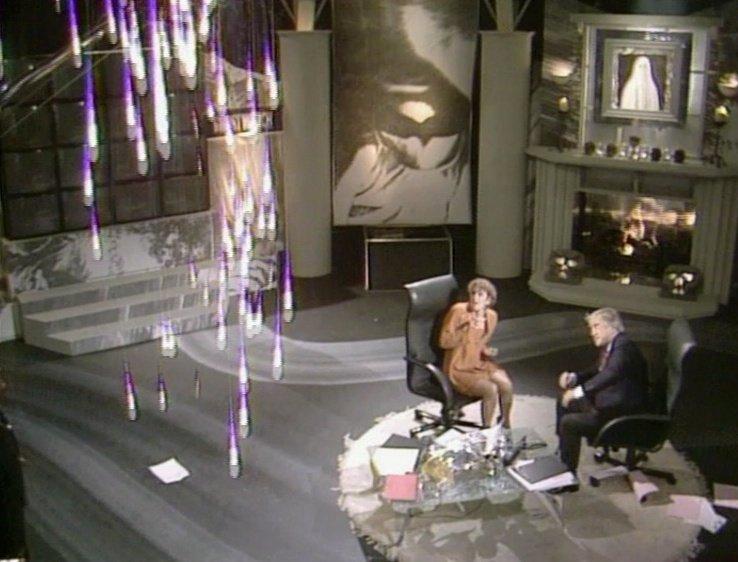

Or so it appeared. It was an intriguing premise. Veteran broadcaster Michael Parkinson would anchor a studio discussion about the supernatural while an outside broadcast from a purportedly haunted house on a council estate in Northolt, north-west London, would be fronted by Craig Charles and Sarah Greene, with Greene’s husband Mike Smith also performing presenter duties at the BBC.

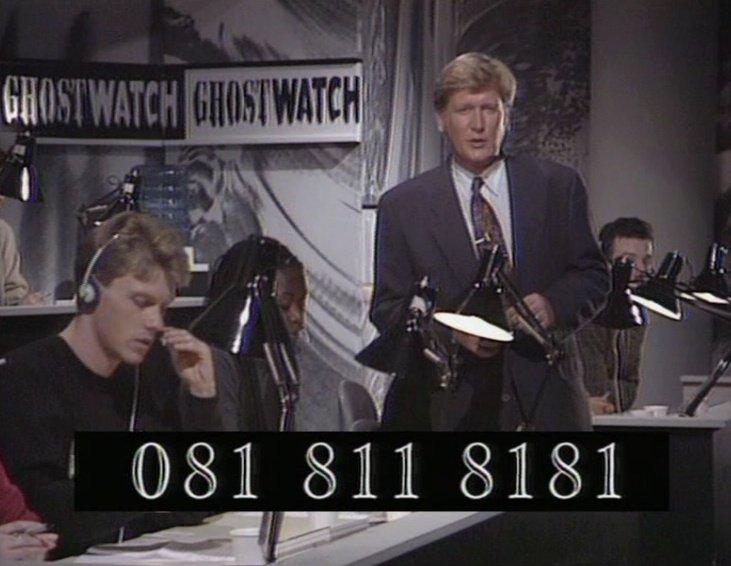

It was novel and entertaining. A procession of experts either talking up or debunking the paranormal joined Parky in the studio. Charles and Greene interviewed people on the street of this estate, kids messing about in the background. There were veiled words about unusual, unsettling happenings in one particular house lived in by a very ordinary family. As the show progressed, people would phone in with their own brushes with the supernatural, including the occasional drunk ringing up for larks.

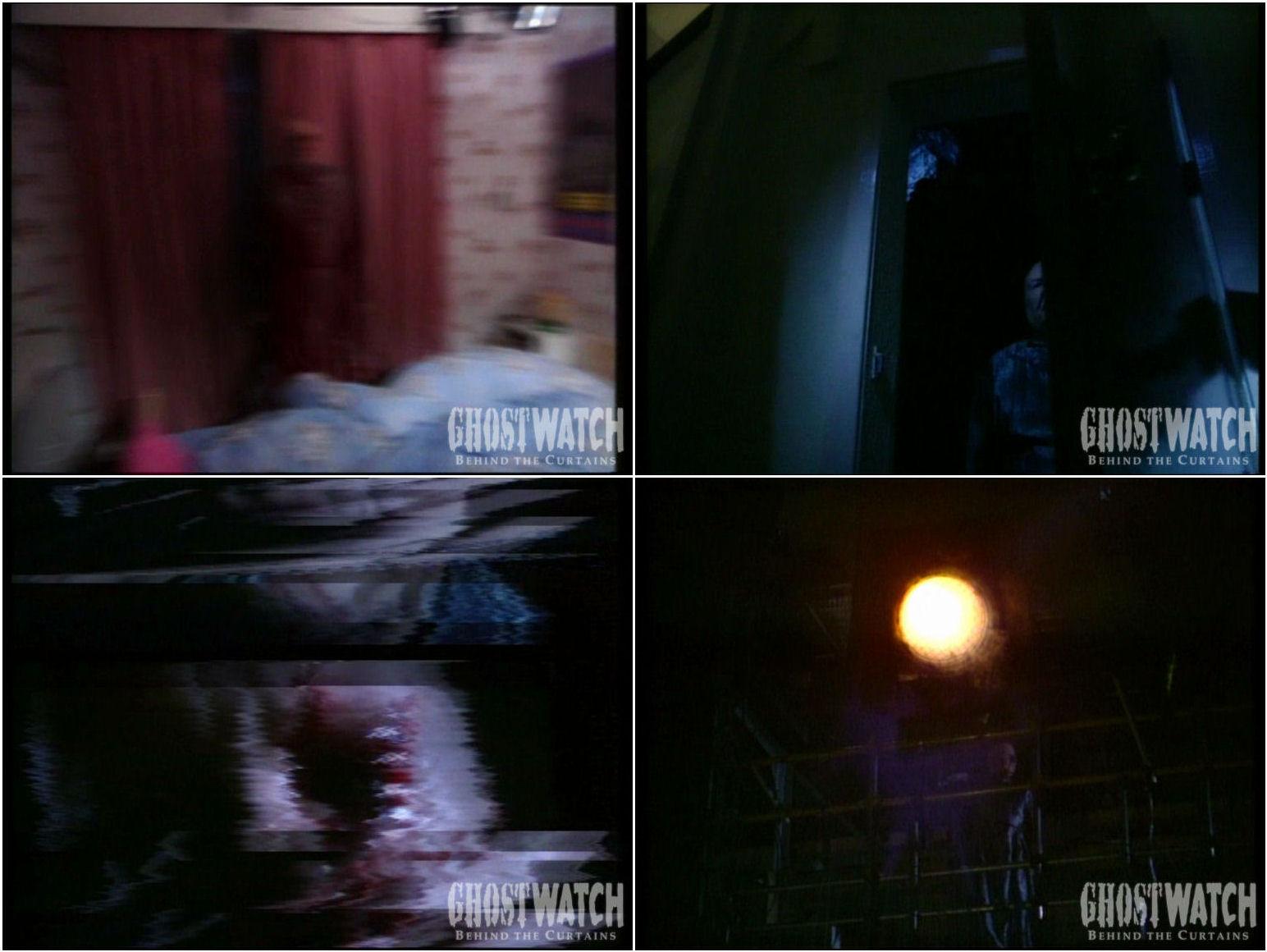

For the first half of the 90-minute show, I think I was utterly convinced. Then it took a more sinister turn, as the small girls in the family spoke of a malevolent entity they called Pipes (because their mother explained the mysterious banging noises away as merely the rattling of the central heating system) they believed haunted their house. Then it spiralled into full-on horror which accelerated towards a truly apocalyptic finale.

Throughout the second half I swung the other way and realised it was a scripted show. But I kept having moments of doubt, sitting there in that B&B room, with its unfamiliar creaks and shadowy corners, and at one point near the end – when a visibly distressed Mike Smith starts to panic about losing contact with his wife at the outside broadcast, where things have gone tremendously wrong – I began to have my doubts again.

“That’s wonderful!” says Stephen Volk with a rich laugh. It’s precisely the reaction he was hoping for. Volk was the screenwriter of Ghostwatch, which wasn’t true at all. It wasn’t even a live broadcast; the outdoor scenes had been filmed over the summer, the production team judiciously scattering pumpkins and Halloween decorations around. But it was never Volk’s intention to fool or prank people; it was a piece of scripted drama made to look like a live broadcast.

Volk had already earned his chops as a screenwriter before Ghostwatch, most famously with a screenwriting credit for Ken Russell’s 1986 film Gothic, based on the infamous night when Mary Shelley created Frankenstein. He had been in discussions with BBC producer Ruth Baumgarten about an idea he wanted to bring to the broadcaster.

“Initially, I envisaged Ghostwatch as a full series about a television crew and a psychic investigator in a haunted house,” says Volk. “The idea fell on deaf ears at the BBC but Ruth persisted and eventually came up with the idea of using it in the one-off drama slot.”

Volk set to reworking the concept, and hit upon the idea of presenting it as though it was a live broadcast. It was a format that, while familiar today, wasn’t hugely common even in the early 1990s; there were factual programmes such as Panorama, light entertainment shows (Ghostwatch was preceded in the schedules that night by The Generation Game and Noel’s House Party that Halloween night), and dramas. The live, telethon broadcast was usually reserved for charity events such as Children in Need.

“I suppose we’d recognise the format today as the sort of programme that’s on early evening, like The One Show,” says Volk. “Throughout the writing drafts I’d thrown in names of real-life presenters, mainly for my own amusement, but when we got the final cast, with Michael Parkinson, and Sarah Greene, I was really, really pleased.”

It was those familiar faces that gave the show its verisimilitude. Surely, we thought, deep down, if no less an august personage than Parky is fronting this, how can it be anything but genuine?

The reaction to Ghostwatch perhaps seems odd to young people today, paints us that watched it as credulous and gullible. But it was a simpler, spoiler-free world. There had been little pre-publicity, no scenes from the show trailered. The absence of the internet meant there was no pre-show discussion, there were no big newspaper features beforehand on what a hoot it was to make. With no social media, there were no tweetathons from fellow viewers decrying the whole thing as just a drama to take comfort in. We were in our living rooms, or hotel rooms, and we were on our own with this thing.

“It was a very different type of writing that I was used to,” says Volk. “I had to create a structure that wasn’t usual, had to have the first 45 minutes with not a lot happening, and a lot of exposition from people being interviewed, because that’s how these sort of shows work in real life.”

That said, he says Ghostwatch was “an established type of horror story”. “It’s basically the idea of ‘the wish that goes wrong’,” he says. “People watch a show like that and they really want to see a ghost, even though they know they aren’t going to. And then, suddenly, they do.”

It’s also an examination of human nature, especially our hubris about our contemporary, tech-driven society, says Volk: “It’s about how clever we think we are, but how we set ourselves up for a fall.”

In a prime example of life imitating art, Ghostwatch also begat an entire genre, most often exemplified by the long-running TV show Most Haunted, in which camera crews, presenters and psychic researchers do indeed investigate supposedly haunted houses.

Unlike Ghostwatch, though, nothing every really happens in those shows. And when Ghostwatch really let loose, it did so in a big way. The gradual realisation in the studio that something had gone wrong in the outside broadcast was cemented by the show’s big pay-off; we, as viewers, had unwittingly become part of a massive televisual seance that had taken the horror off our TV screens and invited it directly into our homes. The final shot of Parky, in a darkening studio, reading haltingly from a prompter that was now inexplicably showing the words of a children’s nursery rhyme, faded into black, and left those who were unsure of what they had just seen staring at their silent TVs.

Volk had attended a party on the night of the broadcast to watch it with friends, cast and crew. After the show had aired, producer Baumgarten turned up. “We’ve jammed the switchboard at the BBC,” she said.

Volk remembers, “I laughed, then I looked at her. She was actually white-faced. ‘No,’ she said. ‘The switchboard is actually jammed. With complaints’.”

Ghostwatch had the dubious accolade of being the BBC’s most complained-about show – estimates range from 20,000 to 50,000 complaints. It was also one of the most-watched programmes, with more than 11 million people tuning in. The tabloids had a field day in the following week, and then things took a darker turn. A young man with learning difficulties, Martin Denham, took his own life five days after the programme and his parents blamed Ghostwatch. A couple of years later, a report in the British Medical Journal claimed two cases of actual post-traumatic stress disorder in children who had watched the show.

There were, of course, measures in place for anyone who felt perturbed by Ghostwatch during its broadcast. The BBC phones were actually being staffed by members of the Society for Psychical Research, including Maurice Grosse, the man who investigated the notorious Enfield Poltergeist haunting in the 1970s. They were instructed, straight away, to tell people that what they were viewing was a drama, was not real, and to offer whatever advice they could to those who were ringing with their own paranormal experiences.

The sense of unease was compounded after the show had ended, when the continuity announcer, as if not quite believing what he had just seen himself, quietly announced that Match of the Day was to follow, and said nothing about what had gone before.

“I think the BBC should have come clean at the end,” says Volk. “There could have been a message saying that it was all a drama. There could even have been a 15-minute show talking about how it was made, or some of the issues raised in it.”

One thing Volk is clear about is that Ghostwatch was never intended as a hoax, or a prank. He says, “We never used the word hoax, and it was quite a shock to see the word used in the press in the aftermath. It was never intended as a prank, but as a piece of drama. The producer didn’t want to put out advance screenings or previews because that would have brought the artifice tumbling down. The fact was, it was drama but it was plausible drama, and people believed it.”

The majority of the complaints, such as those aired on the BBC’s feedback show Points of View, centred on the fact that people didn’t expect the BBC to broadcast something like that, something that was ambiguous and downright scary. The BBC didn’t fool you, not like Orson Welles did with his 1940 radio broadcast of War of the Worlds which sent America into a panic. Well, there was the 1957 Panorama April Fool about spaghetti trees, but that didn’t give anyone nightmares.

“In a way,” says Volk, “that was sort of one of the things we were trying to raise, one of the questions we wanted to get the audience to think about. What do you trust? Do you believe something because you’re seeing it on TV, because experts are talking about it?”

The BBC has never broadcast Ghostwatch again, and indeed disowned it for a good decade after it was put out. Eventually the British Film Institute released it on DVD, and occasionally organise screenings of the show. Sometimes Volk will go along, and watch the reactions of those in the audience, who know from the off that it’s a drama but who still make all the right noises in all the right places.

Ghostwatch is just one point on Volk’s screenwriting career – indeed, he’s teamed up with Ghostwatch director Lesley Manning again for his next movie, Extrasensory, which looks at the idea of Russian ESP experiments – but in writing it he’s certainly booked his place in television history.

“I am very proud of it,” he says. “A writer like me wants to create something memorable, and with Ghostwatch I did, even if it does have the ghost of Orson Welles hovering in the background…”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments