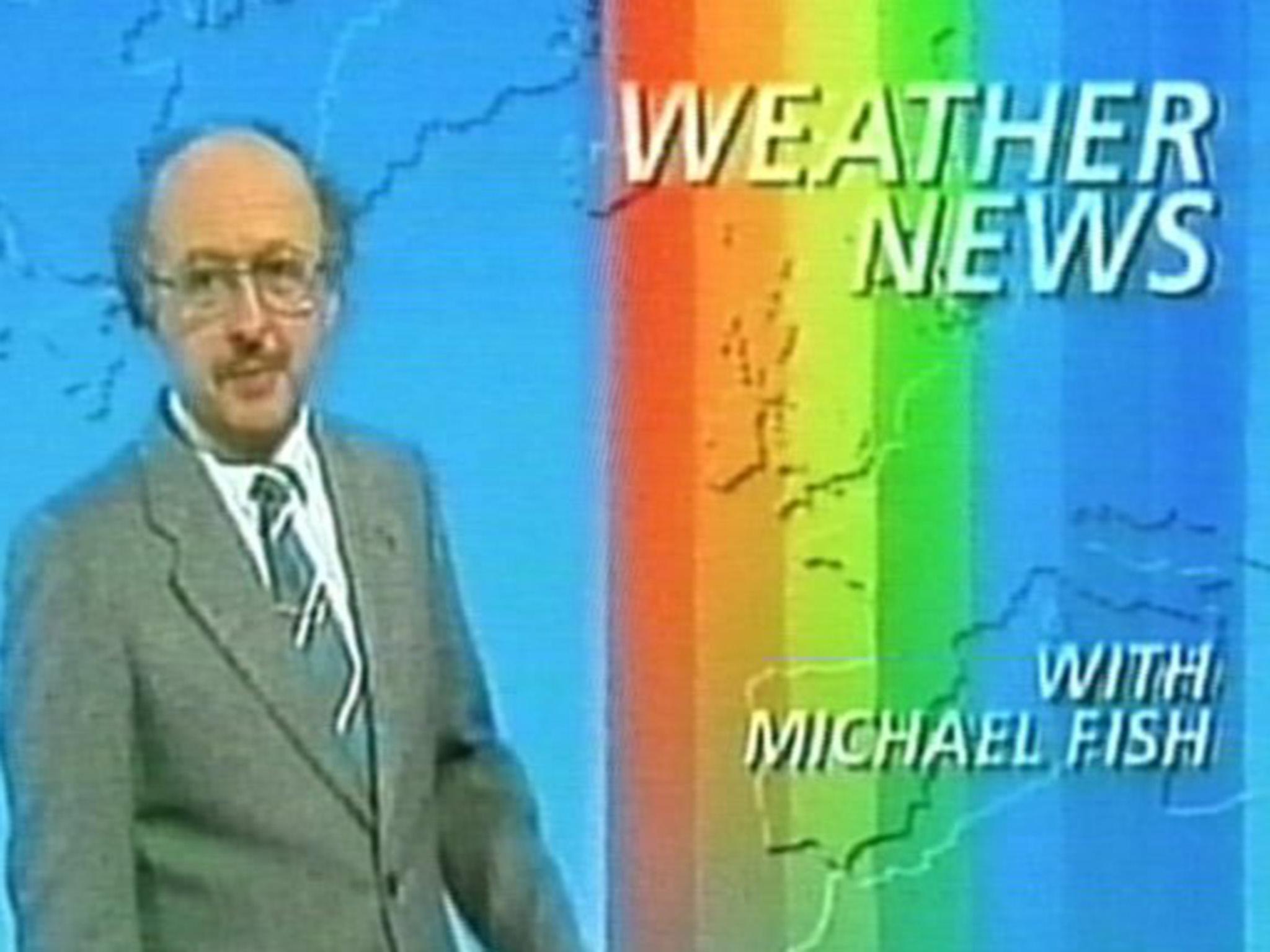

The Great Storm of 1987: Could Britain be taken by surprise again, Michael Fish?

It killed 22 people as it ravaged the UK, 30 years ago. It also created broadcasting gold, with the BBC forecasting that the Great Storm of 1987 was not in fact on its way. Could we still be caught unawares? David Barnett tries to read the runes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Spare a thought for Michael Fish this weekend. Thirty years ago the familiar face of the BBC’s weather broadcasts took up his usual position in front of the meteorological map of the UK and imparted a jovial bit of advice.

“Earlier on today, apparently”, Fish informed the nation on 15 October, 1987, “a woman rang the BBC and said she heard there was a hurricane on the way – well, if you're watching, don't worry, there isn’t!”

As far as it goes, Fish wasn’t wrong. A hurricane is the name for a cyclone that originates in the tropics. The storm that lashed Britain later that evening, while certainly flexing its muscles with hurricane-strength winds, was an extratropical cyclone. But that’s splitting hairs, perhaps, and those who were subjected to the storm – which claimed 22 lives – would not have been arguing the definition.

Fish’s forecast is logged in history. But he would argue that how we remember it is a bit wrong. The broadcaster, who started work at the Met Office in 1962 and retired in 2004, has always maintained that he was talking about a potential hurricane that was thought to be about to hit Florida. In the same broadcast, he has said, he warned Brits to “batten down the hatches, there’s some very windy weather on the way.”

But never let the facts get in the way of a television legend – Fish is resigned to the fact that that’s how he’ll always be remembered. His website features footage of his “infamous broadcast” and accepts that the incident will probably be “engraved on my tombstone”.

And an epitaph to a bygone age of weather forecasting it will remain, because three decades on from the Great Storm, the Met Office has rather stuck its neck out to say it is unlikely to be caught out on the hop in the same way again.

In any case, what exactly was the Great Storm? It began life as a “kink” in a cold front off the Bay of Biscay, marking the boundary between warm air from Africa and colder air originating in the Arctic region.

Where cold air and warm air meet like that there’s a drop in pressure as the warm air rises above the cold, creating clouds and rain. But the pressure dropped quicker and further than usual, for reasons not really fully understood, and it created a deep depression with driving winds that forced it towards the UK.

There might have been more warning of the storm but the media was focused on the industrial action crippling France. And while there had been warnings of gale-force winds in the Bay of Biscay, with little maritime traffic in the area there were fewer first-hand reports on what was brewing.

By the time the storm was noticed by the Met Office it was predicted to follow the path of the English Channel, but its exceptionally low pressure made it unpredictable, and it suddenly veered north over Cornwall and Devon and towards the Midlands and southern England.

There were winds of up to 100mph, widespread disruption and damage to the tune of around £1bn. In the South-east, where the greatest damage occurred, gusts of 80mph were recorded for three to four consecutive hours. The highest gust recorded over the UK was 115mph at Shoreham on the Sussex coast at 3.10am.

According to Fish, “the Met Office was criticised for not forecasting the storm but did no worse than any other National Met Service. The storm was in fact well forecast earlier in the week but later computer forecasts tended to back off and changed the emphasis from wind to rain as it had been so wet up till then and many places were close to flooding.

“As it happened, the soggy ground contributed greatly to the disaster. The trees were still in leaf and could not hold on with their roots in the soggy soil, coupled with the fact that they were attacked from a side that they were not naturally braced for.”

A disaster and a tragedy, for sure. But what the Great Storm did was also blow in a sea change in the way we not only forecast weather and track storms, but also how warnings are given out.

The Met instituted improvements including the “observational coverage of the atmosphere over the ocean to the south and west of the UK... from ships, aircraft, buoys and satellites” and brushing up its computer systems.

Back in 1987, very little data was obtained from satellites, but now the majority of the 215 billion individual weather observations made every single day are provided by the satellite network, which contributes to around 65 per cent of the weather prediction model.

As direct results of the Great Storm, the Met Office was determined not to be caught out by lack of information, especially from the Bay of Biscay, so it located a number of deep-ocean weather buoys all around the waters of the British Isles to provide hourly weather information.

“Supercomputing capability has also hugely advanced since 1987,” says the Met Office. “A typical smartphone of today has a least five times more computer power than our supercomputer of 1987 that could perform four million calculations per second. Today our latest supercomputer is able to perform 14,000 trillion calculations per second helping us to unlock new science and provide more detailed forecasts and warnings.”

This vastly increased computing capacity allows for forecasting models that hone coverage down to the mile – today’s four-day forecast is as accurate as the one-day forecast in 1987.

And there’s also the way we get our information. We don’t have to wait for the weather round-up after the news; we’re constantly connected. Met Office meteorologist and presenter Alex Deakin says: “In 1987 people received their forecasts either via newspapers or at fixed times on TV and radio. Now over 90 per cent of adults consult forecasts via social media, websites or mobile apps. A forecast is now available whenever you want and information about up and coming storms can be accessed in seconds.”

Which means we’re more prepared, as are the authorities. Says the Met: “The three-tier National Severe Weather Warning Service was in introduced following the investigation into the storm and now informs Government, civil contingency stakeholders, emergency responders and the public of the risks of severe weather.”

And in case you were wondering why the Great Storm of 1987 didn’t have a name, as storms do today, that’s a new development, being first introduced in 2015. “This pilot scheme has been well received by the public, raising awareness of severe weather and helping highlight the potential dangers and impacts of storms crossing the UK and Ireland. Names also make it easier to follow a storm’s progress via TV, radio, the internet or social media,” says the Met Office.

But was the Great Storm worthy of its apocalyptic name? Well, it is considered to have been the worst storm since the previous holder of the title in 1703, which felled 4,000 oak trees in the New Forest and brought down 2,000 chimney stacks in London.

It’s considered a once in 200 years event, though Northern Scotland, being closer to the main Atlantic storm tracks, can expect to see winds as strong as those which battered the south-east in 1987 roughly every 30 to 40 years – so any time now.

“We can’t say we won’t see another storm like the one in 1987 but we are able to better forecast and warn of severe weather, helping to minimise the impacts by working with our partners and emergency responders, and the general public to prepare and take action all helping to protect life and property in the future,” maintains the Met Office.

Thirty years on, Michael Fish seems to have reconciled himself with the negative publicity he received over the forecast that never really was, but he’ll doubtless be the name on everyone’s lips this weekend.

Still, take heart, Michael; only a couple of years to go and we can celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Met Office telling us we were in for a “barbecue summer” followed by one of the most miserable summers on record.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments