The ghost trains of northern England that refuse to die

These are the ghost trains – the services that Dr Beeching’s axe missed and that have somehow since escaped closure, and that connect faded seaside resorts, daytrippers, quiet market towns, the odd football fan. Godfrey Holmes rides the rails to a gentler England

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some folk arrive at a railway station crestfallen to find their train’s been delayed or even cancelled. Millions of others turn up, joyfully, to find no trespassers wandering through a tunnel, no leaves on the line, no points failure, no shortage of drivers, and no strike, and so are able enjoy a speedy – and mercifully uneventful – journey. Few people, very few, discover they are about to board a “ghost train”.

Ghost trains at wayside halts unaccustomed to custom. Maybe a new franchisee has had change of heart. Perhaps an ambitious tour operator has hired a special.

Or a sympathetic local council has stumped up some cash. Most commonly, ghost trains run because nobody has ever got round to “doing a Beeching”, thus emulating Dr Richard, the axe-man, who was a bean-counter so successful in his secondment that he closed a third of the nation’s railway network in the 1960s.

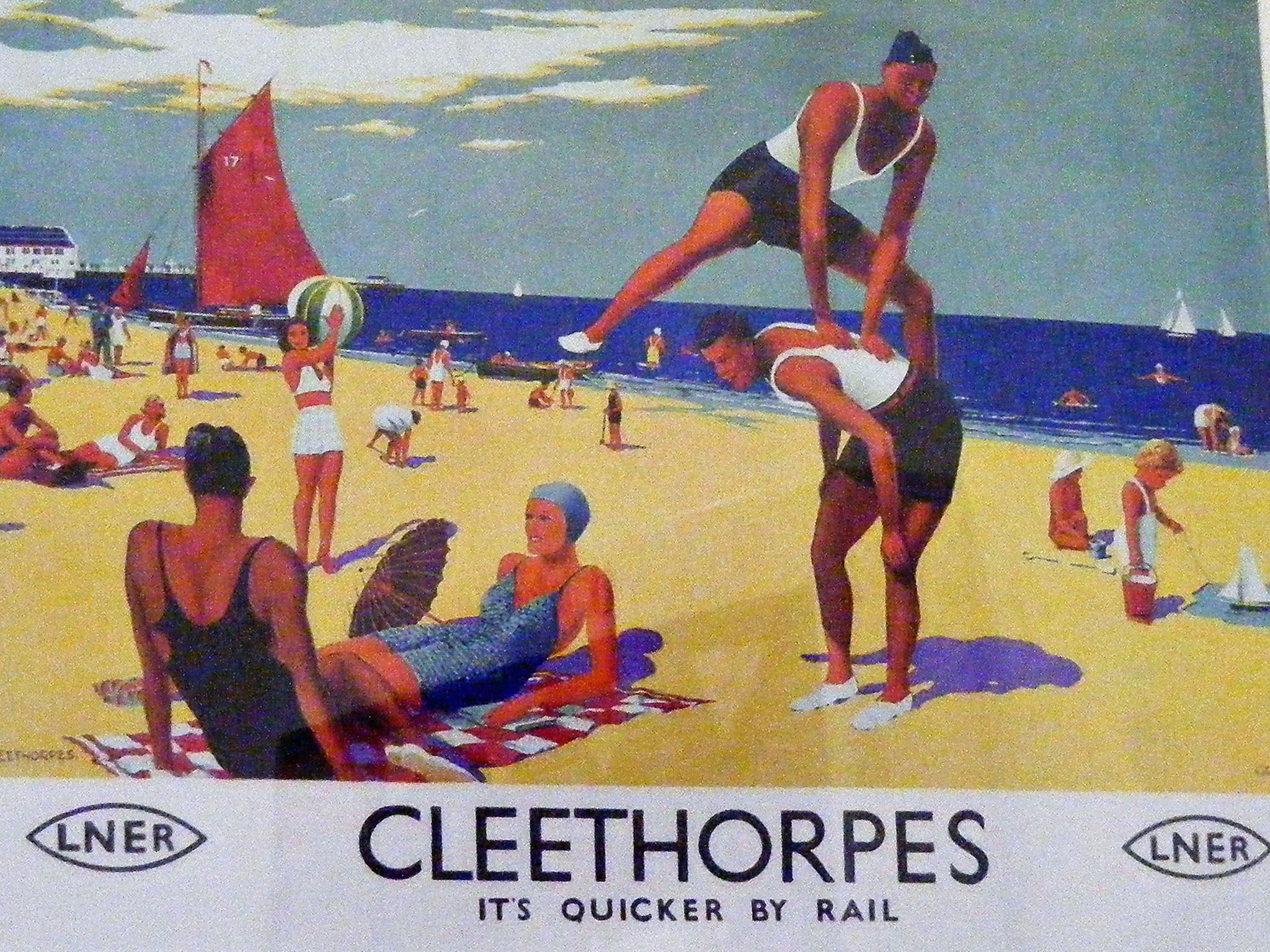

So it was that on one cool autumnal Saturday morning I arrive on the promenade of Cleethorpes, a slightly faded and distinctly unfashionable North East Lincolnshire seaside resort, to catch the 11:14 ghost train to Gainsborough (population 22,117), just over 40 miles away. A gaggle of girls in stylish dresses make the correct platform at exactly 11:11, but only to travel three-and-a-bit miles to Grimsby, there to change for Newark Northgate station. Then comes a pedal-cyclist in dayglow lime. His destination was Barnetby-le-Wold – a sleepy village of 1,500 souls belying its status as a major junction.

“This isn’t a ghost train!” protests one of 10 other men on board. “It’s a proper Sheffield through. I use it every week because I can get off at Woodhouse without going into the city.” Just afterwards, a smartly dressed northern guard did, however, announce through his tannoy that everyone had chosen “the interesting route... via Brigg”.

Brig, Switzerland: Population 13,158, an ancient and historic town on the plain of the River Rhône and first mentioned as Briga in 1215. Railways arrived in 1874; six rail routes including three major passes. Departures: 143 daily.

Brigg, Lincolnshire: Population 5,626, an ancient and historic town on the River Ancholme and first mentioned as Glawemfordbrigge in 1205. Railways arrived in 1848; one rail route. Departures: six if it’s a Saturday – three going north, three south.

When I tried to imagine what a ghost train might look like, I pictured a modified flat-bottomed goods’ wagon – or else a single carriage with an engine both ends: just how I had come from Barton-upon-Humber to New Clee (a journey of 13 miles) at the crack of dawn that same morning.

But I was wrong. This ghost train was a 142 “pacer” – that class of train so despised by railway anoraks and Leeds commuters alike. And that’s because they are relics of the 1980s: an experiment placing 1960s Leyland bus frames on railway wheels. This type of train should have been consigned to the scrapyard years ago; too draughty, too rickety, frequently too cramped. Yet for some obscure reason, the Northern franchise cherished pacers even updated them when other rail operators wouldn’t touch them.

For measuring purposes, I have to be sure which passengers might get off at the village of Barnetby – 18 miles from Cleethorpes. Because they, like the young ladies of Cleethorpes, could be making an entirely different journey such as to Lincoln via Market Rasen (population: 3,904), to Doncaster (population: 304,200) or overseas from Humberside airport. Two people do get off, replaced immediately by four on.

Four Gainsborough-bound passengers make a particular impression on me. The first is a very smart gentleman with an attaché case. Railways have been his life, and as a forthcoming 80th birthday present to himself, he has vowed to travel on every single passenger train in Great Britain. This chosen Saturday – and it is Saturdays only – it is time for ghost train number five. His previous four journeys being Exeter to Okehampton (summer Sundays), Denton to Stalybridge (Friday mornings), Goole to Ferrybridge (weekday early mornings), and Pilning to Patchway, onwards to Taunton (five afternoons a week). I am amazed at this elderly passenger’s amazing ambition – and his resourcefulness.

Second is a late-boarder. A gregarious middle-aged lady with ginger permed hair. She and her husband are going to Brigg Market before heading to one of the town’s hostelries for a drink: using today’s very sparse service simply because it exists.

The third person is a rather elderly woman with a small suitcase on wheels. She, quite understandably, looks anxious – because she is travelling to Gainsborough in response to a family emergency. In that case, Grimsby’s station mistress has done right by directing her to a chance ghost train due any minute, which will save her an hour as the so-called normal train would go via Lincoln.

The fourth passenger I shall never forget actually joined us at Brigg. Paul Johnson of the eponymous Brigg Line Group, founded over a decade ago to vigorously promote railway travel to or via North Lincolnshire.

Rural market towns assume a greater importance than suburbs with far more residents. These towns are focal points for outlying farms and settlements. So for Brigg to be “on the map” it needs good transport. Indeed, until 24 years ago, it did have Monday to Friday trains in addition to a Saturday service boosted by passenger loyalty.

Losing that stopping service on weekdays risked Brigg becoming a backwater. A majority of townspeople think there is no station to use – a perception reinforced by the unwarranted demolition of the actual station buildings, in two stages. Patronage needs winning back.

Until July 2015 and the closure of Britain’s last two collieries – both in South Yorkshire – the village of Kirton’s line did at least host dozens of coal trains in addition to diverted Immingham freight. Could it be that Brigg will soon see just four bio-mass trains passing through each day?

Also, while ever there is neglect, dereliction increases – whether that be fly-tipping, weeds or the crumbling tarmac and falling shelters of Gainsborough Central – a wilderness once described as the worst halt in Britain. At least the presence of Stagecoach buses, Tesco and Gainsborough’s renowned Model Railway Club and Museum are now joining the clamour for more trains on more days to reap the benefits of more passing trade.

Bizarrely, Network Rail did suddenly offer to “upgrade” both Brigg station and Gainsborough Central with the 2014/5 installation of state-of-the-art footbridges: best in the land, each bridge rescuing five or six people a week from the perils of crossing little-used tracks on the level. Cause to rejoice? Hardly. It defies belief that, when the North of England desperately needs ambitious and focused public transport investment, a publicly funded, yet unaccountable, body should squander £400,000, not once but twice: nearly a million pounds misspent on white elephants.

So what of the future? In their discussions with Arriva Northern – the new but reticent franchisee for Brigg – the Government’s Office of Rail Regulation floats the idea of not only timetabling a six-a-day, six-days-a-week, Grimsby to Worksop and Nottingham via Brigg service, but also requiring brand new trains on a Grimsby to London via Lincoln service to stop at Brigg and Gainsborough Central.

In 2016, about 220 people used a train with “Kirton-in- Lindsey” printed on their ticket. Yet on the random day I travel, 35 people boarded the 09:15 train there, heading for a day in Cleethorpes. Also in 2016, no fewer than 1,023 passengers bought: “to Brigg”/“from Brigg” tickets: a number already exceeded in the period 7 January to 7 October 2017.

Even TransPennine Express (operators of Grimsby station, Hull Paragon station, Cleethorpes to Manchester airport and Hull to Leeds) gives valuable space and publicity to the Brigg Line Group. And some Lincoln City football fans now travel the unusual way to their home matches, not only because they miss the last train, but the route is more aesthetically pleasing and it becomes a duty of loyalty for some. Also the brand new, and rather glossy, Gainsborough Travel Guide includes both Brigg and Kirton alongside Gainsborough – a place familiar to readers of George Eliot (who renamed it St Ogg in The Mill on the Floss), all owners of a Marshall’s boiler (where the company was based), all the kings of Mercia (Gainsborough was capital of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom) and all shipping once loading or unloading their cargoes at this the river Trent’s greatest port.

Who knows what potential will be unleashed when those ancient semaphore signals rise and fall a full 24 hours? As I cross to Gainsborough Central’s opposite platform, heading back to Kingston-upon-Hull via Brigg, Barton, and a single-decker bus over the majestic Humber Bridge, I pause for a moment to remember that awful day, in 1984, when the world-famous Settle to Carlisle Line was condemned to death: the ghost of follies past.

Hope springs eternal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments