As foot-and-mouth spread, the government said: ‘Don’t worry, everything’s under control’

In March 2001, the epidemic was reaching breaking point. But, as Michael McCarthy, Stephen Castle and Nigel Morris reported, then agriculture minister Nick Brown thought everything was just dandy

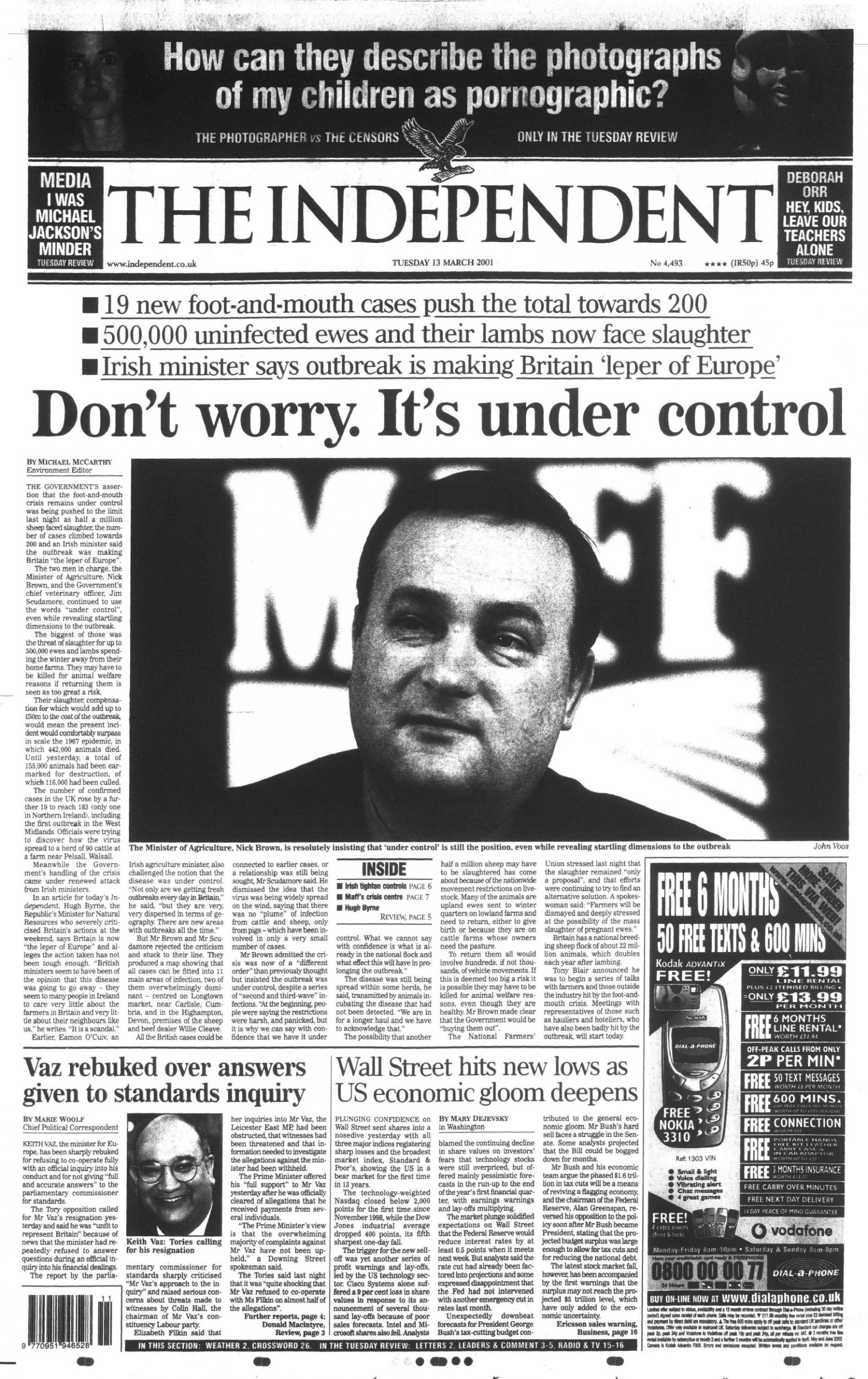

The government’s assertion that the foot-and-mouth crisis remains under control was being pushed to the limit last night as half a million sheep faced slaughter, the number of cases climbed towards 200, and an Irish minister said the outbreak was making Britain “the leper of Europe”. The two men in charge, the minister of agriculture, Nick Brown, and the government’s chief veterinary officer, Jim Scudamore, continued to use the words “under control”, even while revealing startling dimensions to the outbreak.

The biggest of those was the threat of slaughter for up to 500,000 ewes and lambs spending the winter away from their home farms. They may have to be killed for animal welfare reasons if returning them is seen as too great a risk.

Their slaughter, compensation for which would add up to £50m to the cost of the outbreak, would mean the present incident would comfortably surpass in scale the 1967 epidemic, in which 442,000 animals died. Until yesterday, a total of 155,000 animals had been earmarked for slaughter, of which 116,000 had been culled.

The number of confirmed cases in the UK rose by a further 19 to reach 183 (only one in Northern Ireland), including the first outbreak in the West Midlands. Officials were trying to discover how the virus spread to a herd of 90 cattle at a farm near Pelsall, Walsall.

Meanwhile the government’s handling of the crisis came under renewed attack from Irish ministers.

In an article for The Independent, Hugh Byrne, the republic’s minister for natural resources, who severely criticised Britain’s actions at the weekend, says Britain is now “the leper of Europe” and alleges that the action taken has not been tough enough. “British ministers seem to have been of the opinion that this disease was going to go away – they seem to many people in Ireland to care very little about the farmers in Britain and very little about their neighbours like us,” he writes. “It is a scandal.”

In the 1960s, cattle plague shook the UK. Read part five here

Earlier, Eamon O’Cuiv, an Irish agriculture minister, also challenged the notion that the disease was under control. “Not only are we getting fresh outbreaks every day in Britain,” he said, “but they are very, very dispersed in terms of geography. There are new areas with outbreaks all the time.”

But Mr Brown and Mr Scudamore rejected the criticism and stuck to their line. They produced a map showing that all cases can be fitted into 11 main areas of infection, two of them overwhelmingly dominant – centred on Longtown Market, near Carlisle, Cumbria, and in the Highampton, Devon, premises of the sheep and beef dealer Willie Cleave.

All the British cases could be connected to earlier cases, or a relationship was still being sought, Mr Scudamore said. He dismissed the idea that the virus was being widely spread on the wind, saying that there was no “plume” of infection from cattle and sheep, only from pigs – which have only been involved in a very small number of cases.

Mr Brown admitted the crisis was now of a “different order” than previously thought but insisted the outbreak was under control, despite a series of “second and third-wave infections”. “At the beginning people were saying the restrictions were very harsh, and panicked, but it is why we can say with confidence that we have it under control. What we cannot say with confidence is what is already in the national flock and what effect this will have in prolonging the outbreak.”

The disease was still being spread within some herds, he said, transmitted by animals incubating the disease that had not been detected. “We are in for a longer haul and we have to acknowledge that.”

The possibility that another half a million sheep may have to be slaughtered has come about because of the nationwide movement restrictions on livestock. Many of the animals are upland ewes sent to winter quarters on lowland farms and need to return, either to give birth or because they are on cattle farms whose owners need the pasture.

To return them all would involve hundreds, if not thousands of vehicle movements. If this is deemed too big a risk it is possible they may have to be killed for animal welfare reasons, even though they are healthy. Mr Brown made clear that the government would be “buying them out”.

The National Farmers’ Union stressed last night that the slaughter remained “only a proposal”, and that efforts were continuing to try to find an alternative solution.

A spokeswoman said: “Farmers will be dismayed and deeply stressed at the possibility of the mass slaughter of pregnant ewes.”

Britain has a national breeding sheep flock of about 22 million animals, which doubles each year after lambing.

Tony Blair announced he was to begin a series of talks with farmers and those outside the industry hit by the foot-and-mouth crisis. Meetings with representatives of those such as hauliers and hoteliers, who have also been badly hit by the outbreak, will start today.

This article first appeared in The Independent on 13 March 2001

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments