The fall and rise of one of the most beautiful museums in the world

The history of Folkwang isn’t just a story about modern art – it’s a story about the ruination and redemption of modern Germany, writes William Cook

In Essen, a grey and gritty city in the centre of Europe’s biggest rustbelt, Germany’s most beautiful art gallery is celebrating its (slightly belated) centenary. Founded in 1922, Essen’s Folkwang Museum turned 100 last year, but those celebrations were curtailed by Covid-19. This year, it’s an international rendezvous again. Wandering around this serene, sunlit building, you rub shoulders with art lovers from all around the world.

In Berlin or Munich this would be no big deal, but here in Essen? This drab conurbation lies in the heart of the Ruhr, a post-industrial sprawl of derelict coal mines and redundant steel mills, which stretches for over 100km (62 miles) across northwest Germany like a huge unsightly rash. The slag heaps have been grassed over, and new forests now grow where steelworks once stood, but nobody in their right mind would call it pretty. So how did Essen end up with what Paul J Sachs (co-founder of New York’s Museum of Modern Art) called “the most beautiful museum in the world”?

For art buffs, the history of the Folkwang Museum is fascinating – but its significance stretches way beyond the narrow confines of the art world. The Folkwang’s fall and rise isn’t just a story about modern art, it’s a story about the ruination and redemption of modern Germany – from the tyranny of the Third Reich to today’s Bundesrepublik.

The Folkwang encapsulates this story, and so, to discover how it started, I travelled across the Ruhrpott (as locals call it), from bustling Essen to humdrum Hagen, to visit the ornate villa where Germany’s modern art movement began.

Like virtually every city in the Ruhr, Hagen was bombed flat by the RAF during the Second World War and rebuilt in a dreadful hurry – a sociologist’s paradise of bland, anonymous apartment blocks. Only a handful of older buildings survived – most notably the Osthaus Museum, the gallery I’ve come to see today. Built in 1902, it’s a masterpiece of Jugendstil (Germanic Art Nouveau). However, it’s not the building that’s so significant, but the farsighted man who built it.

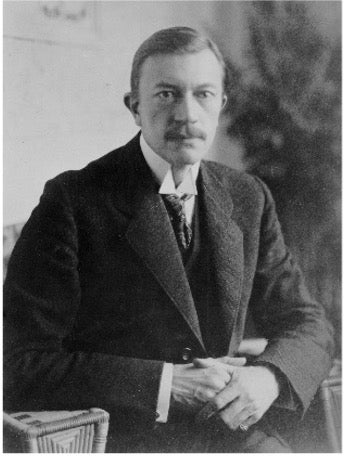

Karl Ernst Osthaus was the scion of a wealthy family who’d made a fortune from manufacturing in the Ruhr. However, instead of following his father into the family business, Osthaus devoted his life (and his vast wealth) to art. He established this museum here in Hagen to showcase his collection, and called it the Folkwang, after the mystical meadow of Norse mythology that was guarded by Freya, the Viking goddess of fertility and beauty.

Collecting art was a popular pastime for Germany’s industrial upper class. What set Osthaus apart was his passion for modern art. Rather than buying and displaying respectable paintings by established artists, he patronised a new generation of German painters, in particular a group of young upstarts from Dresden known as Die Brucke (The Bridge).

These precocious artists aimed to bridge the gap between Europe and the developing world – between European painters, such as Van Gogh, and art from Africa and Asia. Unlike the French Impressionists, who’d focused primarily on the play of light, their paintings were driven by raw emotion. The result was a powerful new genre, unlike anything that had come before.

Osthaus was the first connoisseur to recognise the group’s nascent talent. He bought their paintings, for good prices, but he was more than a collector: he encouraged and nurtured them; he mounted their first exhibitions; he defended them against conservative critics who attacked the “sensationalism” of their “barbaric” pictures and dismissed them as inept and crude.

“We have to face the works of these young artists without prejudice,” declared Osthaus. His gallery became a place of pilgrimage, not only for fans of modern art, but for the emerging artists whom he lionised: Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, among others. They are now renowned throughout the art world, but back then were entirely unknown.

Osthaus also supported the other key component of what became known as German Expressionism – a group of artists called Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), led by Franz Marc and August Macke. These Bavarian artists were less intense than the moody artists of Die Brucke, focusing on pastoral rather than urban subjects, but even though their style was gentler, it was just as radical. Their dreamlike landscapes were windows on a new world.

Osthaus also cultivated two up-and-coming Austrian artists: Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka – both of them now household names, but back then more or less unheard of. The Folkwang Museum was the first gallery to show these artists, and the only gallery in the world to show Schiele during his lifetime. “It was crucial for the development of Expressionist art,” says Professor Peter Gorschluter, director of the Folkwang. As he explains, the Folkwang was the first gallery that was entirely dedicated to modern art.

However, the Folkwang was more than just a gallery. It was a place where artists could live and work. Today the idea of artists in residence is widespread, but what Osthaus did back then was something new. “He really wanted to bring art and people together,” says Gorschluter. “He really believed in the power of art to make a better life and a better society.”

The First World War was a catastrophe for Osthaus, and for his beloved Folkwang: Marc and Macke enlisted, and died fighting on the Western Front; the money Osthaus had to spend on art was drastically reduced. When Osthaus died, in 1921, aged 46, his family were forced to sell his art collection. A consortium from Essen came up with the highest bid.

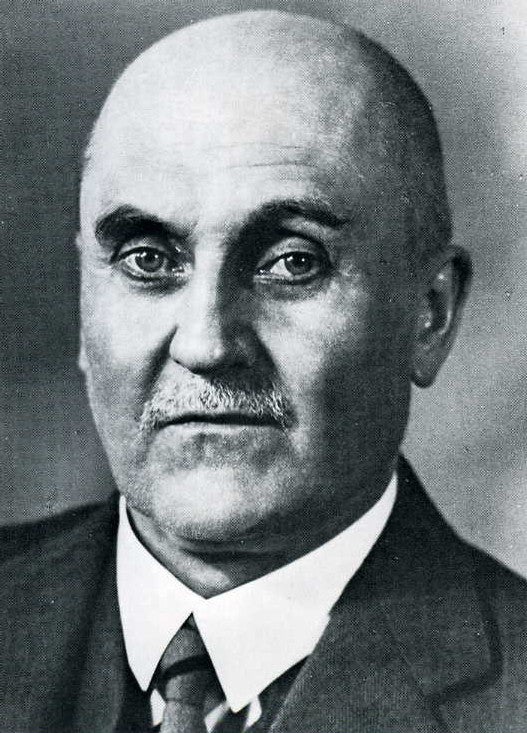

The new Folkwang Museum in Essen combined the Osthaus collection with several other Modernist collections, making it Germany’s most important museum of contemporary art. An elegant new building was erected to house this magnificent collection, and an innovative director, Ernst Gosebruch, was hired to oversee it.

Gosebruch carried on where Osthaus had left off, working closely with Expressionist artists and expanding the museum’s modern collection. A great communicator with a talent for making modern art accessible, he mixed and matched artworks from different continents and different eras – standard practice nowadays, but groundbreaking in the 1920s. When American curator Paul J Sachs came here in 1932 and called it the world’s most beautiful museum, he couldn’t have guessed its greatest treasures were about to be looted by the German government.

When Hitler came to power, in 1933, he declared war on modern art, and denounced all Modernist artists as “degenerate.” All over Germany, his acolytes were quick to follow suit. Progressive curators were replaced, with the painters Osthaus had promoted now facing persecution. The Folkwang’s liberal director, Gosebruch, was replaced by Klaus von Baudissin, a Nazi Party member and a strident opponent of modern art.

In 1937, the Nazi government set about removing all “degenerate” artworks from public galleries throughout Germany, actively supported by Nazi curators like Von Baudissin. Numerous galleries lost countless artworks, but as the gallery with the best Modernist collection, the Folkwang lost most of all – around 1,400 works in total. Some were destroyed; most were sold abroad. The Folkwang building remained intact, but it was nothing without these modern masterworks. The world’s most beautiful museum was no more.

By 1945, almost all of Essen lay in ruins, including the Folkwang Museum. The entire city had to be rebuilt from scratch. People were living in cellars, scavenging for food. Hunger and disease were rife. Germans called it Stunde Null – Hour Zero, a point of total annihilation. You would have thought that art would be the last thing on anyone’s mind.

And yet, amid the rubble, something strange and surprising happened – something that confirmed the rejuvenating, life-enhancing power of art. In a devastated city full of displaced people, lacking the most basic amenities, disgraced, defeated Germans set about restoring the gallery Osthaus had created. “There’s a longing for culture after the Nazi years, when a lot of culture was prohibited,” explains Gorschluter. Suppressed by the Nazis, German Expressionism was a symbol of liberation from the Third Reich.

The victorious Allies also had a vested interest in reviving German Expressionism. In communist East Germany, Socialist Realism (pictures of happy workers toiling contentedly in state-run farms and factories) was the only acceptable artistic genre. In West German cities like Essen, the Allies promoted its aesthetic opposite – experimental, expressionistic art. German Expressionism became a badge of freedom, the art of a people free to make their true feelings known.

The first manifestations of this unlikely renaissance were makeshift exhibitions in temporary spaces – shows devoted to Die Brucke and Der Blaue Reiter, artists the Folkwang had championed and the Nazis had banned. In 1958, the Folkwang Museum reopened, rebuilt on the same site in a bold new Modernist style. However, it wasn’t the building that had made the Folkwang beautiful, but the artworks within it. Now the most pressing task was to replace the collection that the Nazis had destroyed.

“I set myself three goals,” said Paul Vogt – the Folkwang’s influential director for 25 years, from the early Sixties to the late Eighties. “To retrieve what had been lost, as far as possible, or to replace it with works of similar quality, and to document developments that had not existed under Osthaus or Gosebruch.” After all, he argued, the Folkwang had always been a gallery of the present. Restoring its German Expressionist collection was a priority, but this pioneering museum should never just focus on the past.

Under Vogt and his successors, the Folkwang bought back some of the works it had lost before the war, but these reacquisitions were fairly limited – 26 artworks, less than 2 per cent of the missing work. The problem was, most of the artworks the Nazis had seized ended up in international museums that had no intention of reselling them. Generally, the Folkwang could only buy back works that had ended up in private collections and subsequently came up for auction.

Therefore, rather than trying to simply buy back specific works, the Folkwang pursued a policy of acquiring similar artworks by the same artists. This strategy proved spectacularly successful. Today the gallery boasts an even bigger Expressionist collection than the one it lost in 1937. Heckel, one of the founders of Die Brucke, left more than a thousand works to the Folkwang. Private collectors of German Expressionism made generous bequests.

The first time I visited the Folkwang, 20 years ago, its growing collection was still crowded into the compact building that had been here since 1958. When I returned in 2010, that old gallery had been transformed by a stunning new extension, a light and airy space designed by British architect Sir David Chipperfield. “It was enormously important – that really boosted the museum,” says Gorschluter. Finally, after a century of turmoil, the gallery Karl Ernst Osthaus created could be called beautiful again.

Yet true beauty consists of something more than amazing art or architecture. It means nothing without morality, and that’s why the most important artwork in this museum isn’t a German Expressionist painting by Heckel or Kirchner, but a far older picture – Mountain Landscape with Rainbow, painted by the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich.

This painting belonged to the Hirschland family, a German Jewish banking dynasty based in Essen. Georg Hirschland played a leading role in the foundation of the Folkwang. In 1938, his family were forced to flee – they weren’t allowed to take their art collection with them. In 1939, under the auspices of the Nazis, Mountain Landscape with Rainbow was “acquired” by the Folkwang. In 1950, it was returned to Hirschland’s family. Yet in an astonishing act of reconciliation, Georg’s widow Elsbeth subsequently gave it back to the Folkwang, where it hangs today. The Folkwang is a wonderful gallery full of wonderful artworks, but this extraordinary example of forgiveness is more beautiful than any building or any painting could aspire to be.

For information about art in Germany, visit www.germany.travel. For details about the Folkwang Museum, visit www.museum-folkwang.de

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments