The athletes from nowhere: Dispatches from the Faroe Islands, a proud sporting nation the Olympics won't acknowledge

The Faroe Islands has a rich sporting history and are members of the Paralympics, Fifa and several other international federations. But when it comes to the Olympics, they are left out in the cold

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was supposed to be one of the happiest days of his life.

On Friday 5 August 2016, Pál Joensen and 119 other Danish athletes followed Caroline Wozniacki out of the bowels of the Maracanã Stadium and into the full glare of the world’s spotlight, as several thousand camera lenses flashed in unison like fireflies. The group moved slowly, squeezed between much smaller delegations from Cuba and Djibouti, pausing frequently to wave into the glare of the luminous crowd.

Like the other men Joensen wore a smart navy Jack & Jones suit despite the temperature, the only concession to the evening’s stifling heat a red and white striped tee in lieu of a button down shirt. Walking near the front of the group, he made a concerted effort to patiently drink in the splendour despite the blur of movement both before and behind him. Because, although this was his second Olympic Games, it was his first opening ceremony. In London, he had no time for such luxury, with the 400m freestyle heats inconveniently scheduled for the very first day of competition, ensuring he was tucked up in bed for an early night.

But in Rio he had been gifted more time to prepare, more time to enjoy. He had waited years for this moment as had all those athletes who surrounded him: a lifetime’s yearning condensed into a slow, celebratory shuffle from one side of a stadium to another, a moment he had worked so hard to achieve and yet with the promise of an even greater achievement on the horizon. This was it. The distillation of his dream.

And yet there was a problem. A few problems, in fact. For starters, the logo embroidered onto his breast pocket was not the logo of his Olympic federation. And the fluttering wisp of red fabric leading the congregation was not his flag. And the beaming athletes he walked among may have been his team-mates, but they were not his compatriots. Because — and despite all evidence to the contrary — Pál Joensen is not Danish.

He was not born in Denmark. He had not grown up in Denmark. And he will never consider himself to be from Denmark. Joensen is instead from the Faroe Islands, an autonomous country located some 700 miles away, with its own language, culture and flag. And a country with its own Olympic federation, albeit one persistently ignored by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the non-governmental authority responsible for running the Games.

Which rather begs the question: why? Why is a country that is a founding member of the International Paralympic Committee, one that sits closer to Scotland than Denmark and takes pride in its own recognised football, volleyball and handball teams, not recognised by the IOC despite the existence of an Olympic Committee since 1982? And why are athletes such as Joensen not allowed to represent their country of birth at the Olympics, despite competing with a Faroese flag on their chest at a multitude of other international tournaments?

There is no easy answer, despite the IOC’s protestations otherwise. Which leaves Faroese sport in limbo and athletes from the country facing a stark choice: compete for a foreign flag or sacrifice your Olympic dream. Unsurprisingly the Faroese are desperate for this to change, this year launching a campaign to push the IOC into finally affording them Olympic recognition.

“Thomas Bach speaks about the Olympic spirit being ‘for all and everyone’, but why does all and everyone not include the Faroe Islands?” asks Jon Hestoy, the Vice President of the Faroese Olympic Committee, on a visit to London at the start of summer. “We really feel that the Olympic spirit would be a reason to let us in and it’s not just a case of fighting for recognition to get on the gravy train. I just wish people could visit the Faroe Islands for themselves and see what it is this small country has to offer.”

So, with less than two years to go until Tokyo 2020 and 35 years since the establishment of an exceptionally frustrated Faroese Olympic Committee, I caught the short flight from Edinburgh to the small village of Sørvágur to find out exactly what he meant.

TÓRSHAVN

It is a frigid Friday night in Tórshavn, the smallest capital city in Europe with a population around ten times smaller than the Isle of Wight. Not that you would know that on this particular evening, where the narrow roads that sharply wind from the port to the small administrative district team with people celebrating mentanarnáttin — or ‘Culture Night’ — in Scandinavia’s discombobulating midnight sun. A large group of teenagers sing traditional folk songs in the city centre. An even larger group mulls around to watch. And shopkeepers lean next to wide open doors, with customers languidly flitting from one to the next, pint glass or something warmer in hand.

Over dinner on the harbour, Hestoy, my first port of call, holds court. The restaurant is an impressively gnarled old 18th-century warehouse: rough stone walls dimly lit, wooden tables made from the mast of an old sailing ship masted just outside, a menu containing all manner of extravagantly prepared fish. By the time the main course is brought out — melt in the mouth cod with brown butter and pumpkin seeds — Hestoy is already in full flow.

In between mouthfuls of food, his palpable sense of frustration grows, as he explains to me how his small country came to be left out in the cold. “Everybody that we meet within the IOC knows of the Faroese problem,” he says. “And there is always an answer: you have to be independent. It is the mantra of the IOC. So our aim is to get people to ask: why? Why is it that the Faroe Islands are not recognised? Why are they part of the Paralympic movement? Why do we have this rule? And why can it not be changed?

“We have been in close contact with the IOC for many years but the door to membership has been repeatedly slammed in our face. And taking on the Olympic movement is a big ask. We all knew this was going to be an uphill struggle, but it is increasingly feeling as though we are stood on the north side of Mount Everest gazing up.”

Hestoy sighs. In his youth he was an outstanding swimmer himself, representing the Faroe Islands with distinction at numerous international events before retiring and moving into a series of administrative positions. First the president of the national swimming federation. Then a new role with the Olympic Committee. He even travelled to Rio in 2016 to help set up the 10k Marathon Swim Course. But navigating the murky waters of the Olympic movement is without a doubt his biggest challenge yet.

On the surface, at least, the IOC’s argument is simple. The Faroe Islands have been a self-governing region of Denmark since 1948, ruling on all issues except for foreign policy and defence. It is not, therefore, an independent sovereign state, and isn’t considered as such by the United Nations. Factor in an Olympic charter change in 1996 — which ruled that NOC recognition can “only be granted after recognition as an independent state by the international community” — and it begins to look like an open-and-shut case. The Faroe Islands is not an independent state. Therefore the Faroe Islands is not entitled to an Olympic team.

But as the dessert begins to be passed around, Hestoy contends this is an all too simplistic argument that fails to take into consideration a wealth of mitigating factors. Several countries — from Aruba to Bermuda, Guam to Puerto Rico — are in similar political situations to the Faroese and yet were recognised by the IOC prior to 1996, meaning they are free to compete. And then there’s the fact that Kosovo and Chinese Taipei both compete at the Games, despite limited international recognition. Meanwhile all sport on the island is entirely self-funded, with eight different international federations circumventing the IOC by recognising the Faroe Islands.

And then there’s Denmark. You would be forgiven for thinking the country has little interest in seeing the Faroese obtain their sporting freedom given the potential political ramifications, as well as the added boon of being able to cherry-pick their best athletes every four years. But that couldn’t be further from the truth. The Danish Olympic Committee has repeatedly offered its support to their Faroese counterparts, while the Danish Prime Minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, has also spoken out on their behalf. “I would consider it quite natural and would welcome that also the Faroe Islands obtain recognition in the IOC on an equal footing with other members, which have similar status as the Faroe Islands,” he said on a recent visit to the islands.

The next day, Hestoy leads me through the muddled streets of Tinganes — ‘The Thing’ — the historical core of Tórshavn since the Viking era and one of three oldest parliamentary meeting places in the world, along with Tynwald Hill in the Isle of Man and Þingvellir in nearby Iceland. And yet, as with most things in the Faroe Islands, its unassuming significance is easy to miss. We walk towards a small spit of rocky land jutting out abruptly between two harbours, where several blood red, turf-roofed buildings cluster together. The furthest away from us is Føroya Landssýri, the seat of the Faroese Home Rule government, where Poul Michelsen, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, is waiting for us.

Michelsen, who turned 74 earlier this month, is slender, white-haired and oddly regal, in the way that those who have spent a lifetime in public service so often are. He was elected mayor of Tórshavn in 1981. In 1984 he was first elected as a member of the Løgting, the Faroese parliament. And in 2011 he even helped to form a new political party, the pro-Faroese independence Framsókn. But it is not to talk politics that Hestoy has led me to Michelsen. Quite the opposite.

“This is not a political issue,” he says simply, sipping his coffee. (Like the rest of Tórshavn, Michelsen was out late cerebrating mentanarnáttin with his family.) “Whether you are unionist or republican does not matter when it comes to this issue, because everybody is united. And when we are in Parliament there is never a debate on whether we should push for recognition or not. The only debate is how much money we commit to the project.”

Later, the Minister of Education, Research and Culture, Rigmor Dam, corroborates Michelsen’s claims that this is an issue of national importance that goes beyond politics. Dam, a social democrat who represents the centre-left Javnaðarflokkurin party, is a Unionist and yet reiterates that Denmark and the Faroe Islands are two entirely different nations.

“This is not a political struggle between us and Denmark,” she says. “In regards to culture and sport we are an independent country from Denmark, we have our own language, our own culture, history and sports. We don't feel Danish at all in this way and they don't feel Faroese at all. So as a Unionist politician I can say that we are supporting this bid fully.”

And yet despite this unprecedented level of co-operation across the political spectrum, as well as the full support of Denmark, the IOC still appear to be wary of the political backlash of handing Olympic recognition to the Faroe Islands. I ask Hestoy how frustrating this is given the united front of all Faroese lawmakers. “It is very frustrating for us, who have all worked hard on this campaign,” he nods. “But it is the athletes who most suffer. That is a question you need to ask them.”

KLAKSVÍK

There are 37 different words for fog in the Faroe Islands. Slavtoka is a rainy mist. Mjørkabrúgv is a fog bank that sits on the horizon. Hjallamjørki is a thick belt of fog, above and below which it is tantalisingly clear. And fjallamjørki is a mountain fog, which descends from the heavens in a matter of seconds, covering the Faroe Islands’ small settlements like a burst of breath on a window pane.

During my trip to Klaksvík I encountered at least two dozen of these different types of fog, or mjørki. The weather in the Faroe Islands changes endlessly, as dramatic microclimates form around the huge mountain peaks and steep sea-cliffs which rise suddenly from the teal Atlantic, and it is not uncommon to enter one of the country’s many tunnels struggling to see for fog, only to emerge a few minutes later into brilliant, blinding sunlight.

Fortunately, however, when I arrive at Við Djúpumýrar, the football stadium of local team KÍ Klaksvík, the fog has vanished completely as if somebody had turned on a gigantic fan, only slightly out of sight. On an artificial pitch the first team are being put through a vigorous training session, while in a gymnasium next to the pitch two cleaners are tidying up after a handball match. However, it is to the small swimming pool around the corner that I am led to, to meet the next great hope of Faroese sport.

Like the modest gravity of Tinganes, Signhild Joensen rather defies expectation. Still just 17 years old, she doesn’t look like much of a future international star, with a round youthful-looking face and quiet demeanour — a million miles away from the arrogant young sports stars we are accustomed to in the UK. But her talent is impossible to ignore. She competed in the 200m backstroke event at the 2017 World Aquatics Championships and has already achieved a qualifying time for Tokyo 2020. And all before she is old enough to vote.

There is a catch, of course. To compete in Japan, she would need to secure one of the top two times in Denmark to win a place on their Olympic team. “It is definitely a bit awkward,” she says, as we walk around the sports centre. “Because we compete with them with our times but obviously they feel as though they should have first preference because it is their country, and we are foreigners who might take their spot.”

Not that the awkwardness would be the worst thing about substituting the Faroese flag that currently decorates her blue training jacket for the red and white Scandinavian cross of Denmark. “My biggest dream is to compete at the Olympics, but it is also my dream to compete under my own flag. Competing for Denmark is not the same and makes us feel as though we do not have the same rights as everybody else.”

Rather than attempt to solve the issue once and for all, the IOC has until now swept it firmly under the rug, leading to Faroese athletes being repeatedly stripped of their nationality as if they have done something wrong. “We competed at the 2015 European Games in Baku,” Joensen remembers. “And we were not allowed to use the Faroe flag. Instead we had to compete as LEN (Ligue Européenne de Natation) and were given tee-shirts with no flag, just plain blue with our name. And when we were introduced our name was read out with no nationality. It felt like a punishment because we wanted to show where we came from but we did not have the chance. We were from nowhere.”

But not every athlete from the Faeroes is an athlete from nowhere, forced into a plain tee-shirt with no room for a flag, all cultural and national legacy stripped away like bark from a tree. There is a popular joke in the Faroe Islands: that the only way to proudly represent your country is to have a disability of some description. And after speaking with Joensen I meet with Tóra við Keldu, a resident of Klaksvík and former swimmer who won four medals across the 1988 and 1992 Paralympic Games. Crucially, she won them for the Faroe Islands.

The country was a founding member of the International Paralympic Committee back in September 1989 and has sent athletes to every Paralympic Games since 1984, winning 13 medals in the process. Such success has, however, done little to bolster their campaign in the eyes of the IOC: along with Macau, an autonomous region on the south coast of China, the Faroe Islands are one of only two territories to compete at the Paralympics but not at the Olympics.

For Keldu, there is no question that competing for the Faroe Islands augmented her Paralympic experience, helping her to extract every last drop of her talent in an attempt to win a medal. “Of course it influences you,” she nods. “The sport will always come first. But when you see and hear the people around the pool, and then when you stop after winning a race and hear the national anthem being played, it’s such an important feeling. It is important for us as a nation that, if we are called the Faroe Islands nation with our language, culture, scenery and flag, we also compete in sport.”

Katrin Dagbjartsdóttir goes even further. A fellow Paralympic swimmer, Dagbjartsdóttir competed alongside Keldu at the 1988 Games in Seoul, winning a bronze in the 100m backstroke and silver in the 100m freestyle. Between them, the the two women are responsible for just under half of the all the medals the country has won at the Paralympic Games, and Dagbjartsdóttir brings both of hers to show me when we later meet for a chat.

As Dagbjartsdóttir talks, she absent-mindedly fiddles with the scuffed dark blue box that contains both of her Paralympic medals, as well as numerous others from World Cups, European Cups and Nordic Championships. Fiercely passionate, she speaks plainly of how representing the Faroese flag inspired her to success in swimming meets across the world.

“Seeing the Faroese flag when you compete at competitions is crucial for a Faroese athlete,” she insists. “We are not Danish at all. Training year in and year out is hard — and then to compete for the Danish flag? We should be competing against Danish athletes for our own country and under our own flag. That is how it is at the Paralympics but not at the Olympics, which is a huge mistake.”

Dagbjartsdóttir is now a coach at the Tórshavn swim club — “as a swimmer I am almost a dinosaur but my results are still here, so I make a good coach” — helping the next generation of Faroese athletes to reach their potential. But every time she watches one of her swimmers set a new record time, or push that little bit harder in training, there is a worry. “Because of this rule I fear we will lose all of our best athletes to Denmark,” she explains. “And that is terrible for sport in our country.”

But coaches like Dagbjartsdóttir do not only worry about losing their talented young athletes to Denmark. As their students grow older — and the demands on their time multiply and escalate — they also have to worry about the persistent influence of the most popular sport in the country, one which is largely immune from the difficulties caused by the lack of IOC recognition: football.

RUNAVÍK

Jens Martin Knudsen is stood in the centre circle of NSÍ Runavík’s home ground, wearing an Adidas Faroe Islands technical jacket from a few seasons back, with his face scrunched up to the heavens, remembering the past.

“The one thing that everybody in the team was focused on was making sure that we didn’t lose by ten goals or more,” he says, thinking back to 12 September 1990, when he woke up feeling both giddy with excitement and sick with nerves. It would ultimately prove to be the defining day of his life. “When we all heard the national anthem I suddenly realised that there was a lot of pressure. Honestly, we felt like lambs going to the slaughter. But most of all I was just desperate not to lose 10-0 and feel like the biggest fucking fool in the world, picking the ball out of my net with a bobble hat on my head.”

Ah yes, the bobble hat. It’s Knudsen’s calling card, not to mention the title of his autobiography. The story goes like this: Knudsen, a three-time Faroese gymnast champion in his youth, suffered a concussion aged 14 and was only allowed to return to the football field by his mother if he did so wearing a ‘protective’ woollen hat. Quite what a knitted bobble hat would have done to protect him from hulking great target-men lumbering after an errant back pass is anybody’s guess, but Knudsen didn’t dare go against the wishes of his mother, staying true to his word until — one day — he wound up wearing the beanie in the Faroe Island’s first ever competitive football match, against Austria.

But the bobble hat didn’t mark him out as a fool. Instead, it became the stuff of legend. Public opinion had been well and truly divided when the Faroe Islands first approached Fifa seeking international recognition — “people were split half and half, some were proud and some where excited, but others thought we were crazy and would get stuffed every single match”, he admits — but against all the odds, the Faroe Islands would go on to beat Austria 1-0, with Torkil Nielsen scoring the winning goal and Knudsen pulling off a string of impressive saves. “After that there were no more doubters,” he smiles. “After that everybody was 100 per cent behind us.”

Winning that match changed the entire sporting psychology of the country. Knudsen cannot help but glow at the memory. “You can imagine the euphoria on the island. This was before mobile phones and so on, and we were forced to play the game in Sweden because we had no grass pitches. I called home on an old corded telephone to tell my family what happened and there was a big parade when we arrived the day after, all the way from the airport to the capital. There was a big celebration in Tórshavn and then we went out and met all of the local communities. It lasted a full day.”

Atli Gregersen, the current captain of the Faroe Islands national team, remembers watching the game as an excited eight-year-old around his grandparents’ house, the entire family hunched around a flickering screen. And then, disaster. “We couldn’t see the first ten minutes of the game because the electricity across the whole of the Faroese went, and there was obviously no internet. We were all like ‘fuck, when the picture comes back on is it going to be 10-0 already?’ And I remember the picture came back on and the score was still 0-0, and we all danced around the house like we had won.”

Expectations have changed a lot since those black-and-white days. Gregersen — who enjoyed a brief spell at Scottish side Ross County and now plays for title-winning local team Víkingur Gøta — has captained the Faroe Islands through their most successful ever era. As recently as 2007, the national side was ranked 195th in the world, one place below war-torn Somalia and only three places above Bhutan, now officially the worst team in the world. Currently the Faroese are up to 90th, finishing above both Latvia and Andorra in their recent World Cup qualifying group. “And we would have won a point against Portugal,” Gregersen is quick to add, “only some bloke called Cristiano Ronaldo decided to turn it on.”

Gregersen, who is dressed identically to Knudsen albeit in this season’s Macron branded kit, is a footballer through and through: confident, charismatic and with a wisecrack primed for every possibly eventuality. He also speaks with a curiously Scottish twang, his answers peppered with ayes, aboots and wees. And he is justifiably proud of how far the national team has come in such a short period of time.

“It’s different now, everything has changed,” he tells me in between sips of coffee, having joined us in the middle of the pitch. It’s now early evening and yet, through breaks in the fog, the sun still shines as bright as ever. “We no longer get looked down upon by teams and we get the recognition we deserve, although it doesn’t do us any favours. So the ambition is to qualify for Euro 2020. And we think we can do well in the new Uefa Nations League project, too.”

But the success of the Faroe Islands football team may have come at a price. Both Gregersen and Knudsen are well aware of it. “When you’re 14, if you’re at good at several sports and you end up having to pick the one you want to stick with, you will always pick the one with the most opportunities,” Gregersen says. “And for a very, very long time in the Faroe Islands, that meant that you stuck with football.”

This is a key part of the Faroese argument with the IOC. The potential to compete internationally has seen football in the Faroe Islands flourish, not only on the international stage but at grassroots level. A total of 22 synthetic pitches serve both semi-professional and youth clubs, while Fifa has invested in over 100 concrete pitches dotted around the country. Consider that the total population stands at just 51,000 and the depth of the Faroese love for football becomes clear.

But for other sports in the country — starved of international recognition and therefore starved of investment — life is not as easy. Talented youngsters therefore face a choice: to stick to their sport of choice but resign themselves to only competing domestically, or, alternatively, switch their focus to football. The only other option? To switch their nationality from Faroese to Danish.

Gregersen is convinced this has to change. “If we get the recognition that we need and deserve, it would give a major lift to all of the other sports in this country. It would be a little difficult for football, sure, but we’re ready for that. It’s not fair that people who are better at table tennis or handball end up choosing football, only to fall short and then miss out on their opportunity to become internationals. It’s really not fair, but it’s inevitable.”

This is not the fight of the Faroese football team. But the Faroe Islands is a small country, where everybody knows everyone and local ties run deep. “We are football men so we don’t feel the frustration quite as much,” Gregersen says. “But for other sports the dream just dies as soon as a kid hits 14. They are not allowed to compete and if only on a human level, that is very sad. It honestly hurt me a lot to see Pál Joensen swimming for Denmark.”

Beside him, Knudsen nods his bobble-less head gravely. “We want to create something here,” he adds. “How can we do that when our very best athletes, like Pál, are forced to represent a totally different country?”

RETURN TO TÓRSHAVN

It would be impossible to write anything about this country’s long fight for Olympic recognition without sitting down with Pál Joensen. Now 27 and with a young family settled in — of all places — Denmark, he is not confident of his chances of competing in Tokyo in two years time. But he remains every inch the national hero.

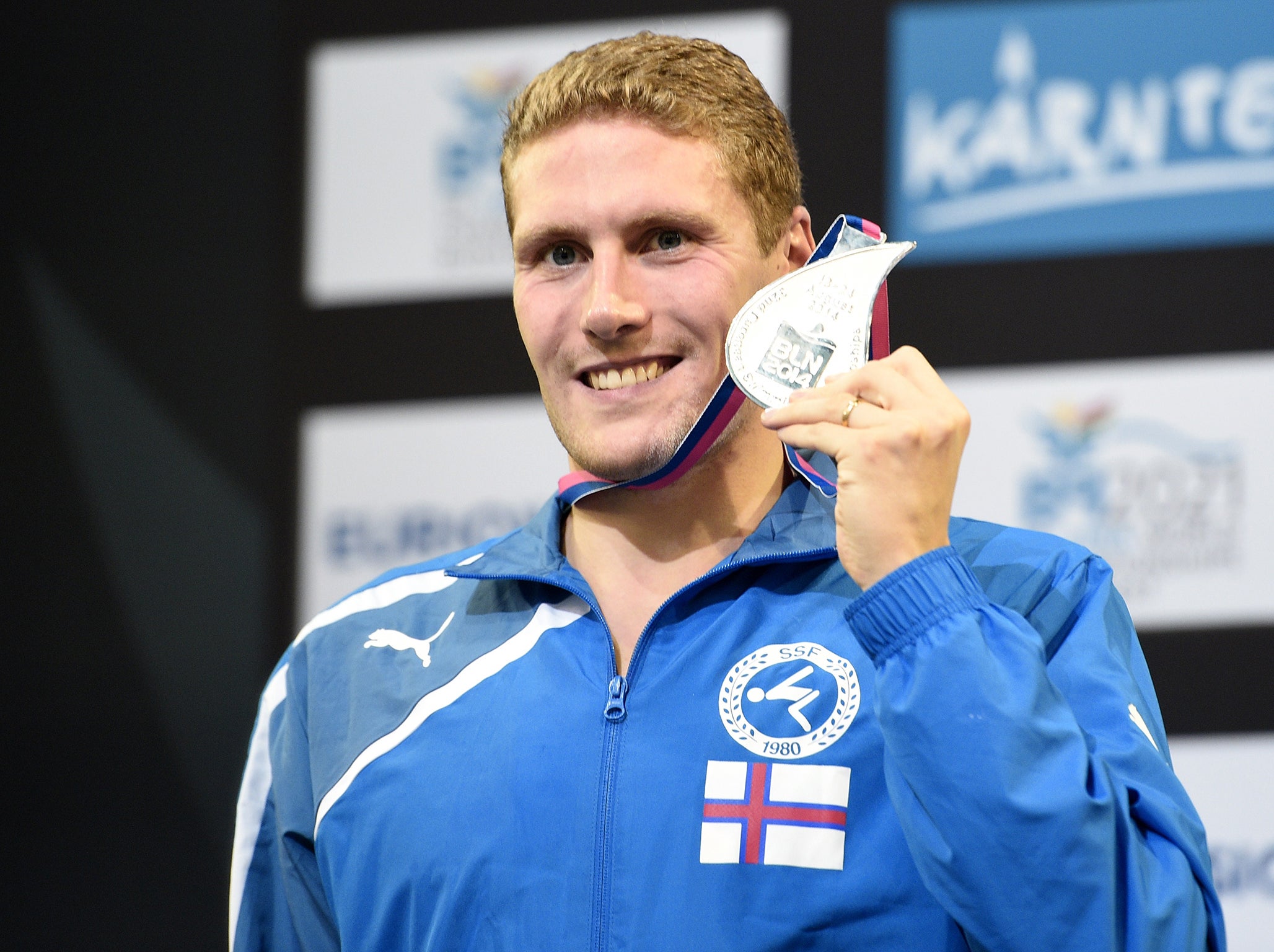

“He is our greatest ever athlete and the most humble person you could wish to meet,” Hestoy told me the night before I met Joensen. “The entire country stopped to watch him race in London and Rio, and everybody felt so proud.” He’s not kidding: “We have 18 swimming pools in the Faeroes including one Olympic sized pool, which we named after Pál. It was built after the 2010 European Championships in Budapest, when he won a silver medal in the 1500m free.”

But unusually for a national hero revered by all, Joensen’s two Olympic Games ended in bitter disappointment. First London, where he had a TV crew and two radio stations follow his every move at the Aquatics Centre, only to finish ninth in the 400m freestyle and a disappointing 17th overall in the 1500m. He was seen as a major medal contender in both. ‘Joensen’s Olympic dream lasts only 500m’ ran one particularly cruel Daily Telegraph headline. And then Rio. Again, Joensen entered the 1500m free as one of the favourites for a spot on the podium, as everybody back home in the Faroe Islands stopped whatever it was they were doing to watch him race. And again, he performed beneath himself. His time of 15:18.49 saw him place 30th.

At both Games, he swam for Denmark.

Not that the results have diminished his standing back home in the Faeroes, which is clear to see when meeting him back in Tórshavn. Tall, powerfully built and dressed down in chinos and a knitted jumper — even in the middle of summer, temperatures in the country rarely climb above 11°C — Joensen is stopped regularly by people eager to say hello. He is softly spoken, self-effacing and impossibly laid back. In short: he couldn’t be more Faroese.

Apart from those two Olympic-sized windows when he suddenly became Danish, of course. I pester Joensen with questions on how strange it must have been: did it negatively impact his performances in the pool? Did it cost him his chances of winning a medal? Was it, ultimately, to blame for all the disappointment, all of the hurt? Joensen doesn’t want to say so. But it could have been.

“I was tremendously disappointed with my results at both the 2012 and 2016 Games,” he says without hesitation. “I went into both as a strong contender for a medal and really believed that I could win. I don’t want to come up with excuses because a lot of other factors are involved — including the pressure of competing at an Olympics as well as training changes that were not beneficial to me. But, yeah, thinking about this issue took up a lot of my time and energy and occupied a lot of my emotions. It certainly wasn’t beneficial to me and it affected my focus.”

Any professional athlete will tell you of the importance of visualisation: the psychological process of creating a mental image or intention of what you want to happen or feel in reality. But for Joensen both Games proved something of an alien experience, a befuddling scrabble into the unknown.

He squints at the memory. “It was hard to describe. I’m used to the blue jumpsuit with the Faroese flag. So going in the full Danish kit from Jack & Jones, a good Danish brand, it felt kind of odd. Plus people obviously knew me in the swimming world, but did not necessarily know that I had this issue. So people were coming up to me all the time and asking: ‘Why are you wearing Danish clothes?’

“It was just so weird to represent a country I had never lived in at the time, a country I absolutely did not associate with. And it’s funny because I remember at the start of my career saying that I was never going to swim for Denmark. So I had to ask myself a question: how much am I selling out my nationality and my people? It was extremely difficult because the Olympics cannot be bypassed as a swimmer, they count for everything, and I knew that I couldn’t just bypass them.”

Later that day, we visit a traditional rowing festival. Kappróður is the national sport of the Faroe Islands: the narrow wooden boats have an unmistakably Viking design, with the crews divided into different age, gender and boat size categories. The festival is a celebration of shared history — for hundreds of years boats such as these were the chief method of transport between the eighteen islands — but the racing remains fiercely competitive. From the shore, parents in traditional dress scream as their children row furiously, their wooden oars carving into the delphinium-blue water.

Every single race is competitive. And the relief when the junior rowers cross the line is clear to see: when they compete the course of 1000m they slump backward, the untended boats drifting aimlessly into the billowing fog. Tradition is important here, Joensen tells me. “We are a very proud nation and my dream was always to compete for the Faroe Islands. And I was always determined to help change how the outside world sees us, to show what we can achieve even though we are from this very small country.”

So does he reflect back on his Olympic experience — the training, the opening ceremonies, the competition — with pride? “I have tremendous pride that I came from my kind of background to represent the Faroe Islands on the international stage. And I tried very hard to be proud of representing Denmark.” He pauses, before adding: “But it is not where I came from. And it is not where I had all my support. Ultimately, this is an issue that has to be resolved.”