Why do we keep writing essays, and what does it reveal about us?

The essay is a resurgent art form with an immense history. Andy Martin reads between the lines and meets the finalists of the Notting Hill Editions essay competition, excerpts from whose entries The Independent has been serialising

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

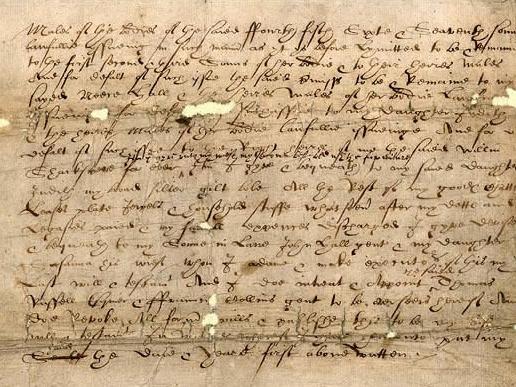

Imagine if Shakespeare had written essays. If he had, then we would know a lot more about the real Shakespeare, the man behind the mask, and there would be less of the maybe-it-was-only-someone-pretending-to-be-Shakespeare line of thought. But even so he was probably influenced by the form of the essay pioneered only a few decades before by Michel de Montaigne. Isn’t the soliloquy an oral kind of essay (and vice versa)? When Hamlet or Macbeth or Falstaff speak of death or daggers or honour they strike a note not dissimilar to Montaigne. Maybe a little more tortured and tragic. But there is the same explicitness and candour. There is always an element of the confessional in the essay. And maybe just a hint of the drama queen.

Consider, for example, “Of Liars”. The part about lying still seems relevant right now, wherever you live in the world. But Montaigne begins by admitting some of his own faults. His memory, he says, is defective. I occasionally stand people up, it is true. But I just want you to know, it’s nothing personal, don’t over-interpret. I’ve just forgotten we had a date, that’s all, it’s purely an intellectual failing, not an emotional one. Whether you agree with him or not (if you really loved me, wouldn’t you have remembered?), you feel that you get to know Michel de Montaigne. In speaking of lying he is trying to be as truthful as possible about himself. The original essayist is a typical Renaissance man in the sense that he is poised between the ancient and the modern, and his language is peppered with classical references (just like Shakespeare), but you still feel as if you could engage him in a reasonable conversation (just as you might Hamlet too, if he existed) because he is, at some level, just like you. The essay is part of (in Harold Bloom’s phrase) “the invention of the human”.

So, what with Montaigne being long gone and all, naturally I had to go and have a word with a few modern-day essayists, who are still around. I thought I really ought to speak to William Max Nelson, the winner of this year’s Notting Hill Editions essay competition. I learned one very big thing from having this conversation, which is now seared into my memory for all time: don’t meet successful essayists in big fancy London hotels – they charge a fortune just to have a cup of coffee. Next time I’m going to meet people in Pret à manger. If I’d known William Max Nelson was just about to be handed a cheque for £20,000 I would have got him to pay.

But here is the thing I was really quite jealous of: he took several years to write one essay, “Five ways of Being a Painting”. I’d like to see what my more deadline-conscious editor would say if I said to her, my idea is to write the first half of this article while I’m juggling lectures around at the University of Toronto, and then the second half after the birth of my first son, tapping thoughts into my phone with one hand, while trying to rock the babe off to sleep using the other arm. Oh yeah, and would you mind paying me £20k when it’s done? I would fear the “hahahahahahahahaha” text. That is the genius of William Max Nelson: he had no fear. He was writing a whole book about “Enlightenment eugenics” or “biopolitics” at the time, and the essay seemed like a vacation, something outside the Academy, more freewheeling and fragmentary, and first-person in perspective. “Having my son was part of it,” he said. He is now 40 years old and his son is two and a half. That’s the essay for you in a nutshell: you are giving birth, but at the same time you are also contemplating your own mortality.

How much research do you have do for an essay? Answer, none. On the other hand, your whole life is research, even though you may not have known it at the time. I had an email exchange with Patrick McGuinness, who wrote “The Future of Nostalgia”, mainly about Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish writer. For McGuinness the essay is “a place on the page where you can do what you want. I've written fragmentary essays, essays in bullet points, essays in verse, essays about things I knew about and essays about things I knew nothing about, where I hoped the essay would help me know more. I've also written essays where I knew less about the subject than I did when I began. That's OK too, I think.” Montaigne, with his “What do I know?” slogan, would have approved. The essay isn’t an accumulation of knowledge or wisdom, maybe more like the opposite.

The genesis of an essay is or should be aleatory. No one can tell you to write a particular essay. “I was standing at Penn Station,” Laura Esther Wolfson said, “going to see my elderly parents and I was looking up at the departures board and I asked myself, ‘Why did I ever stop translating Svetlana Alexeivitch [who had recently won the Nobel prize] – and now I was trying to get the job back (fruitlessly). And I thought, this is a peculiar situation.” Which is how her essay, “Losing the Nobel” (which you can find in the Notting Hill Editions collection) came to be.

I went to meet her in Bayswater (another hotel not quite as ruinously expensive as the last). She is the author of the forthcoming “Proust at Rush Hour” (to be published by Iowa Press) and she carries an oxygen tank around with her. Or wheels it around. In the middle of London she is like a scuba diver, slowly navigating the reefs and sharks. She suffers from a rare disease, L.A.M. (lymphangioleiomyomatosis). As she says, “It’s not possible to pronounce it without getting short of breath.” Maybe that is part of the attraction of the essay, it’s a short form: you stop when you run out of steam.

On account of her illness, Wolfson has had to give up a lot of things: rock climbing, skiing, cycling, swimming, surfing, simultaneous translation (something she was once rather good at, having worked for the United Nations for 15 years), and potential parenthood. Not sex, although this is something that only gets into the essay “tangentially”. “My family read my stuff to find out things about me. I’ve spared them details about my sex life. They’ve suffered enough already.” In our brief encounter I learn that she tends to go in for relationships that are “reckless at the outset” and end with “spectacular breakups”. I think perhaps the essay is rather like that. The essay is not a marriage, it’s a one-night stand, or a romance that is bound to end in tears. Intense but short-lived. Perhaps “turbulent” (to use Wolfson’s word about her own life).

There is something random and eccentric, even chaotic about the essay, the feeling that this particular moment can never occur again in the history of the universe. I felt that when I walk through the door of Dasha Shkurpela’s small apartment on 113th Street in Harlem, New York. Beyond having a door and windows, nothing was quite as you might expect of an apartment. “It’s an artist’s place,” she says. “Everything is the opposite.” Dasha wrote “Dacha” (I can’t help but think they were made for one another) but is a painter and sculptor too. She is from Kyrgyzstan, speaks Russian, studied in Budapest and has been living in New York since 2008, and is now permanently betwixt and between, seeing America from an Asian point of view and Asia from an American point of view. I really want to buy one of her more than life-size self-portraits, done on rolls of paper, in surprising colours, which she kindly unrolls for me on her bed. She reminds me of Jean Cocteau. “You think differently when you type,” she says. Spurred on by a hearty loathing of totalitarianism and what Husserl called “the natural attitude”, she likes to write about “things that are taken for granted”, unregarded buildings and pieces of porcelain and ourselves, “I want to get people to look, to really look at what they might not otherwise see – it’s like a professional obligation. To make the unseen visible.”

Essayists, like essays, are singular (even though plural). Beyond some basic level of literacy, it’s not clear what they have in common. Being alive (for a time), I suppose; and then not. There is a phenomenology of the essay, which is to say I don’t think a machine could come up with one, not a proper essay, just by stringing together odd remnants from a database. It has to have a heart and a pulse, possibly with extra oxygen on the side, and therefore some measure of passion, pride and prejudice. An essay has as much soul as Aretha Franklin or Nina Simone. But there is one stray remark of Laura Esther Wolfson’s, made as I am leaving, that has wormed its way into my head like an annoying jingle. “There is one sentence in there that is not at all reliable.” She didn’t tell me which one. “It’s not my purpose to report,” she adds, mysteriously.

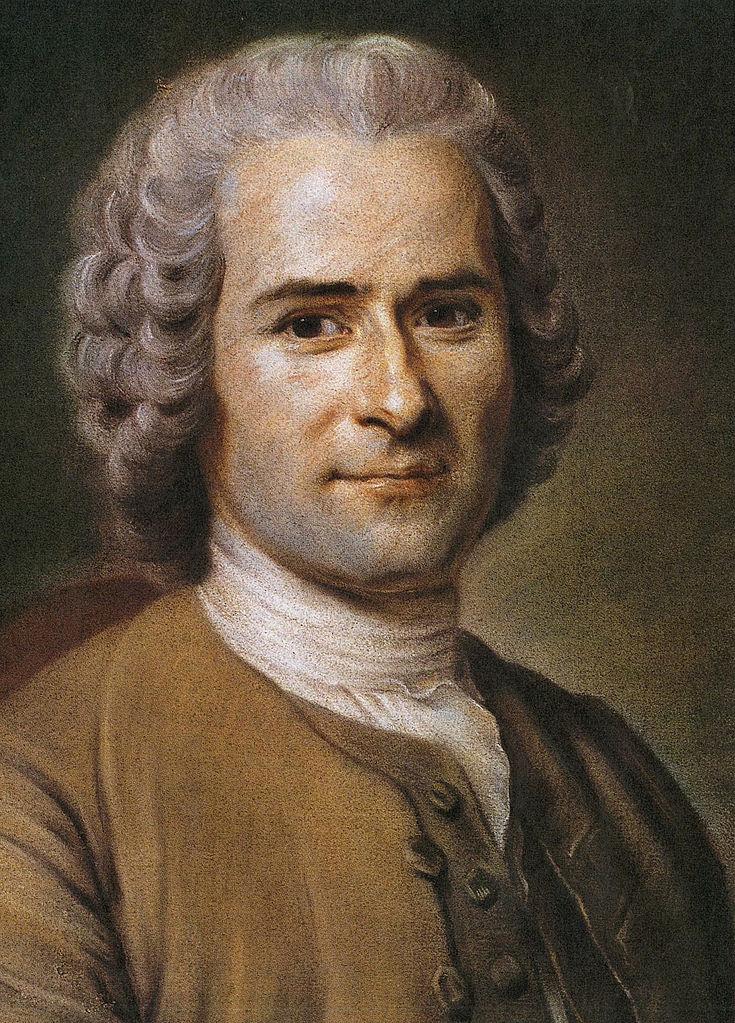

So I am left wondering, which is the unreliable sentence? Is it this one – or this? And then you start to wonder – are any of them entirely reliable? There must always be some degree of doubt hovering over the essay, like a dark halo. Jean-Jacques Rousseau admitted it flat out.

Rousseau got off to a flying start in his essay writing career in 1749 when he submitted his “Discourse on the Arts and Sciences” for a competition run by the Academy of Dijon and won first prize. Maybe that had something to do with the theme of (as it came to be known in English) the “noble savage”, but perhaps it was not unconnected to his honesty (not, note, reliability) in admitting that a lot of it was conjecture. In his subsequent “Discourse on Inequality” he speaks of “a state which no longer exists, perhaps never did exist, and probably never will exist”. It’s not – as in Montaigne – lying as such, but there could be a hypothetical or speculative element. Or a high degree of crankiness. The essay is anything but omniscient and infallible.

On the other hand, it’s not fantasy either. Even if subjective, indeterminate and ultimately unreliable, the world of the essay still has to be recognisably this world, we have to have some common ground. Napoleon Bonaparte saw Rousseau as his role model and submitted his “Essay on Happiness” to the examiners of the Academy of Lyons essay prize. One characteristically Napoleonic feature of his essay which you don’t often come across: a barely veiled threat to retaliate against anyone who didn’t give him top marks. Emotional but also aggressive. “Love me – or else!” that is the gist. And he was an artilleryman after all, even then.

Maybe the examiners should have taken him more seriously, instead of dismissing his work as “a most pronounced dream”. Personally I always fear writing anything too harsh at the bottom of anyone’s essay just in case they go off and become emperor in revenge. I think in the future I will need to interview all those hundreds of would-be essayists that were left out of the Notting Hill Editions volume, just in case.

Andy Martin is the author of “Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me” and teaches at the University of Cambridge. Like Napoleon, he has not won a prize for essay writing, although he did once win a prize for French poetry reading at school. Follow @andymartinink

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments