Employees in full-time jobs worse off than those on zero-hours contracts

With the number of people on zero-hours contracts this year reaching a record high, it’s no surprise that permanent contracts are viewed like gold dust. But full-time jobs can be just as bad, if not worse, when it comes to undermining workers’ rights and underpaying staff

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With the number of people on zero-hours contracts this year reaching a record high, and nearly half of all jobs created since the financial crisis classified as self-employed – many of them low paid or part time – it’s no surprise that permanent contracts are viewed increasingly like gold dust. But what many people don’t realise is that permanent jobs can be just as bad, if not worse, than zero-hours or self-employed contracts when it comes to undermining workers’ rights and underpaying staff.

“People think that permanent contracts are much safer than they are,” says Jonathan Chamberlain, an employment lawyer and partner at Gowling WLG. “All it means is it’s not temporary, whereas it sounds much safer and secure than it actually is.”

One of the ways firms can undermine the security of a permanent position is by putting staff on yearly contracts then giving them an enforced break, effectively laying them off and re-employing them each year. This allows them to ignore employee rights to redundancy pay and against unfair dismissal which accrue after two years’ employment.

One worker who fell foul of such a scheme was a teacher, Colin*, who worked for a private English language college in Dorset. Although Colin had worked for the company for five-and-a-half years, the college laid him off without any redundancy pay after an enforced two-week holiday. Colin felt so harshly treated that he left English teaching as a career. “If someone takes a personal dislike to you they can just get rid of you,” he says. “It encourages management to act in a tyrannical way and that’s really bad.”

According to the TUC this practice is common in further and higher education, where staff are often laid off after nearly two years to avoid redundancy payments. Employees are then rehired a month later, often via an agency, enabling them not only to get around employment obligations but also to pay less for the same skills.

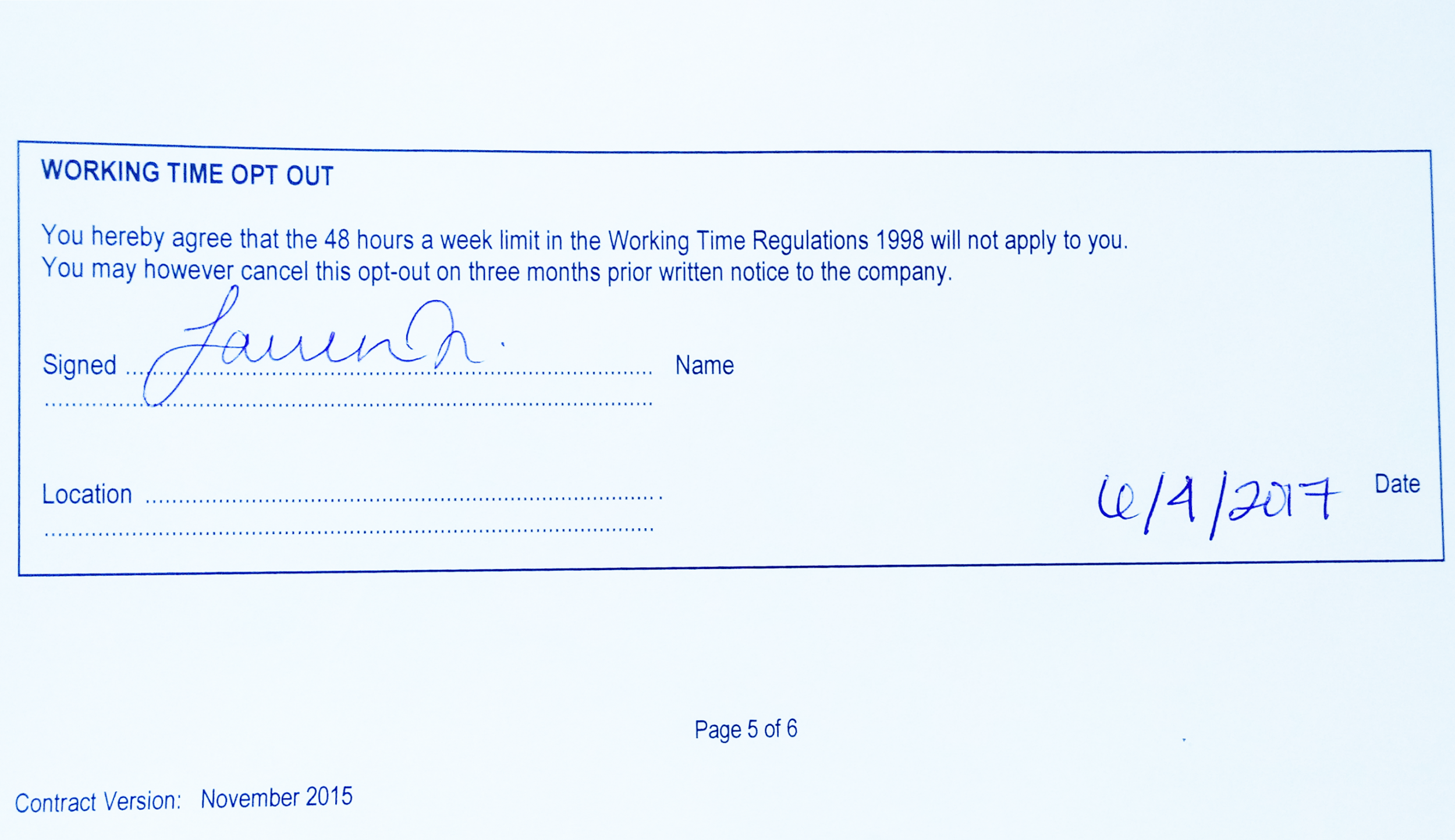

Another way permanent contracts are exploited to underpay staff – often below the minimum wage – is extremely prevalent in the hospitality and catering industry. In hotels and restaurants most long-term staff are employed on permanent contracts, but it doesn’t make their lives any easier. In fact it makes them much worse. Employees on full-time contracts are asked to sign a form agreeing to opt out of the 48-hour maximum working week under the 1998 Working Time Regulations. This allows employers to give staff as many additional hours as they want – often up to 70, 80 or even more a week – and often without pay.

Chris Boyd worked in management positions in various hotels during a 10-year career in the hospitality sector. He fell foul of the 48-hour opt-out agreement in every job he worked. “I’ve always had the disclaimer on day one in my induction pack,” says Boyd. “It’s normal, and I’ve had to give them out to supervisors. If you’re full-time in that industry the company wants you on a salary because then they know what they’re paying you every week.”

In practice this means staff on full-time contracts are often being paid less than minimum wage when worked out on an hourly basis. This was the case for much of Boyd’s career as a manager in the hospitality industry. “I did four-and-a-half years at a small family-run hotel, doing constantly 60-70 hours with a salary based on 40 hours a week,” he says.

“My salary was 20 grand, and if you work that out over 52 weeks at 70 hours, it comes to something like five pound fifty an hour.” This was well under the minimum wage of £6.08/hour at the time Boyd worked there. And it wasn’t just at small family-run hotels, according to Boyd, but well-known and respected chains where this happened. He estimates that it wasn’t until he reached the position of Operations Manager – the second highest management position in a hotel – that he began to regularly earn above minimum wage.

Unfortunately it seems Boyd’s experience is the norm rather than the exception in hospitality and catering, where chefs get a particularly raw deal. According to Philip*, a chef working for a renowned high-end restaurant chain, his company presents the 48-hour opt-out form at interview. It then doesn’t hire the people who don’t sign it. Philip, like most people, signed it and so is forced to work dozens of unpaid extra hours a week. “You get paid for the 48 hours you work pretty much,” he says, “but then after that you’re working another 30 hours a week that you don’t get paid for.” Oliver*, another chef who worked at the same restaurant in 2014, says he worked 80-hour weeks for a three-month period, bringing his salary down to an hourly equivalent of just over £4. “They take advantage of people’s passion for cooking,” says Oliver, “which is exploitation of the worst kind.”

Philip has worked in the industry for seven years and makes it very clear how widespread the practice is, especially at higher-end restaurants. “Any big restaurant, anyone who knows what they’re doing, will do that,” he says. Ironically this means that higher-skilled chefs get worse conditions and pay than relatively unskilled ones. Philip says chefs at his restaurant often joke about going to work at McDonald’s where they would get better pay. Earlier in his career Philip cheffed at one of London’s most famous and renowned hotels. He was forced to work more than a hundred hours a week, much of which was unpaid. In the end his health suffered so badly he was forced to quit. “I got an immunodeficiency virus,” he says. “My immune system was so run down. I wasn’t eating and I wasn’t sleeping. It’s a very unhealthy lifestyle.”

Philip’s case is by no means unique. In fact the problem of unpaid overtime cost UK workers a staggering £33.6bn in 2016 alone according to a report by the TUC. This was the result of 2.1 billion hours of unpaid work last year. And, according to Chamberlain, the practice is not only unfair but in many cases unlawful. “If the number of hours you work means that, when divided into your salary, it comes out as less than the national minimum wage, that’s against the law,” he says. This means that if, as Boyd and Philip claim, most restaurants and hotels operate this policy, then huge numbers of employers in catering and hospitality are breaking the law, including some of our most renowned restaurants and hotels.

And these aren’t the only tricks employers use to pay staff below the minimum wage. Other common schemes, according to the TUC, include not paying staff for compulsory training, or making illegal salary deductions by charging for things such as uniforms, tools, protective gear or transport to site.

How then has something so unfair and, at times, unlawful become so widespread? The answer, according to Chamberlain, lies back in 2013 when the coalition government introduced tribunal fees, making it prohibitively expensive for workers to take employers to court. “Employers are now a lot freer to exploit the workforce than they used to be,” says Chamberlain. “That was a deliberate policy change by the coalition government. Ostensibly it was to raise money to fund the tribunal service, but in fact it was a way, to all intents and purposes, to abolish statutory employment protections for huge swathes of the workforce.” According to a report by the TUC, this single policy change caused the number of work tribunal claims to fall by a massive 79%, most of which were small claims such as those for underpayment.

The long-term effect of this has been a workforce that is effectively prevented from challenging unfair practices by its employers. The upshot for individual workers like Philip and Boyd are long hours, low pay and ultimately, ill health. Philip says there are several people at his restaurant currently suffering from anxiety, depression and addiction problems. Mental health issues and addiction are something he has encountered throughout his career. “It definitely pushes you to the brink,” he says. “There’s a lot of people with drinking problems and drug problems. There’s a lot of people who have depression issues. They’ve got no money and they work their arses off. It can be a pretty depressing place sometimes.”

But apart from all the issues, Philip, like so many other chefs, loves his job. “I didn’t become a chef to make as much money as possible,” he says. “I would just like everyone to get paid for the hours they work.” Chamberlain however wants to see a change in employment law. “The fee system needs to change drastically,” he says. “Employment tribunal fees inhibit access to justice. There are mechanisms for challenging this sort of abuse but unless they are accessible, they are worse than useless because they give the illusion of protection, but it just isn’t there.”

* These names have been changed at the person’s request

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments