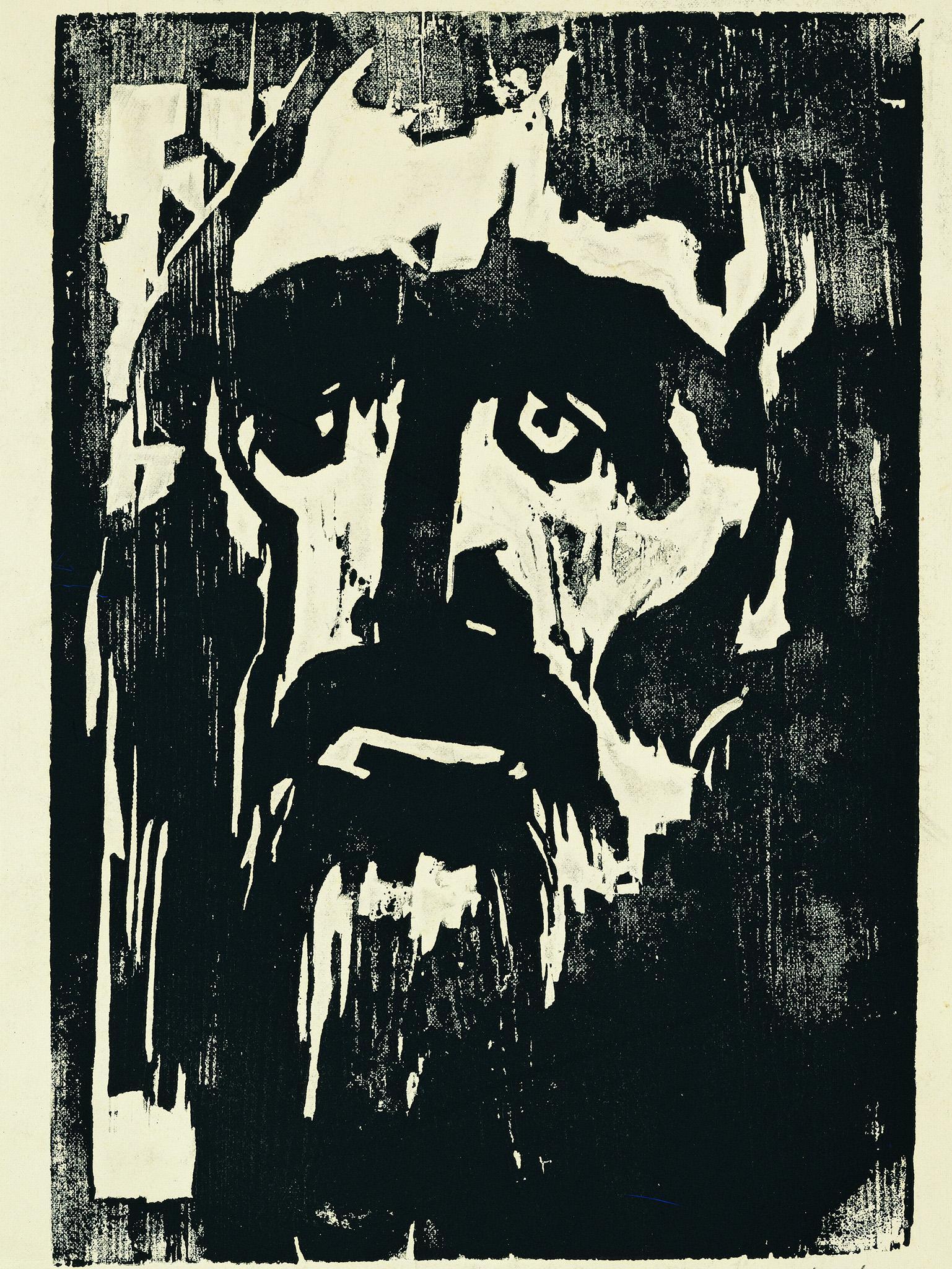

Can you enjoy great art created by a Nazi? New Emile Nolde exhibition explores this dilemma

The big question for our times is whether you can condemn someone’s sexual conduct, and still enjoy their art. In the case of painter Emil Nolde, can we delight in his work even though he was an enthusiastic supporter of Adolf Hitler?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the National Gallery of Ireland, in the historic heart of Dublin, there’s a beautiful painting that encapsulates one of the burning issues of our age: how should we react when bad people make great art?

Two Women in the Garden was painted in 1915 by the German artist Emil Nolde. By modern standards it’s not remotely controversial: two grown women, both fully clothed, standing in a sea of flowers.

Looking at it today (in a wonderful new Nolde retrospective, which travels on to Edinburgh this summer) it’s hard to imagine how it ever caused the slightest fuss. But in 1937 it was condemned by the government of the day as “degenerate” and removed from the gallery in which it was on display. Two Women in the Garden was deemed unfit for public view, and duly confiscated, in much the same way that our own government might censor an obscene picture of a child.

That government in 1937 was Hitler’s National Socialists, and to modern eyes the reason for Nolde’s persecution seems absurd. Alongside countless other great artists, including German Expressionists like Max Beckmann and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, he was accused of perverting German culture by painting in a Modernist (and therefore, as far as as the Nazis were concerned, a Marxist and Jewish) style.

Several thousand “degenerate” pictures were destroyed, including dozens by Nolde, before the Nazis realised that by selling them abroad, they could earn foreign currency for the Reich. Hence Two Women in the Garden (and numerous other “degenerate” masterpieces) survived. In 1984, it was bought by the National Gallery of Ireland. It’s one of the treasures of their collection, and one of the highlights of this landmark show.

Those “degenerate” artists are now revered in Germany, and elsewhere, while the artists the Nazis championed are dismissed as heartless, talentless hacks. Heroes have become villains, and vice versa. It’s a perfect illustration of how attitudes to art – and morality – can change.

“When you look at German art, you can never get away from rupture and upheaval,” says Sean Rainbird, director of the National Gallery of Ireland, as he takes me around this stunning show. But there’s another layer to Nolde’s life story which makes him especially intriguing. Despite his Modernist style, which Hitler loathed, Nolde was a member of the Nazi party. And despite his persecution (over a thousand of his pictures were confiscated, more than any other artist) he remained loyal to that evil empire, the sworn enemy of Modernism, even after it forbade him to sell or exhibit his work.

Nolde is still a controversial artist, just as he was in Germany 80 years ago, when Two Women in the Garden was seized from the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. Yet today, he’s controversial for completely different reasons – not because of his Modernism, which made him a hate figure for the Nazis, but because of his support for that criminal regime.

“He was an enthusiastic party supporter, early on, and he had direct connections,” says Rainbird. “He could sit at the top table with Himmler – he could go to these banquets and be celebrated.” Yet bizarrely, it seems Nolde was not a racist. “For centuries we Europeans have acted towards primitive peoples with inexcusably barbaric greed, destroying entire peoples and races and always under cover of the most noble intentions,” he wrote. “Beasts of prey have no mercy and we white people often have even less.”

If Nolde was merely a second-rate artist, this moral conundrum would be a lot less troubling. Plenty of other people who supported the Nazis have been forgiven and forgotten. It’s the power of his art which makes his story so fascinating – and so disturbing. How could an artist who painted with such humanity and sensitivity support a murderous tyranny which was already persecuting its own citizens long before Germany went to war?

“You can always learn a huge amount about an artist through a greater knowledge of what they’ve written,” says Rainbird. “It’s good to look into the biography if you’ve got the information – but how far?”

Nolde’s initial support for the Nazis can be partly explained by the location of his homeland, on the northern edge of Germany, hard up against the Danish border. After the First World War, and the Treaty of Versailles, his hometown became part of Denmark. When Germany’s borders were redrawn by the victorious allies, millions of Germans ended up living in foreign countries: Denmark, Belgium, Poland… For many patriotic Germans, the Nazis seemed like the only party who’d right this historic wrong.

Other German Expressionists, like Beckmann and Kirchner, had been cured of their nationalism by the horrors of the trenches. Their attitudes were liberal and internationalist, which made them natural opponents of the Third Reich. However Nolde had been too old to fight, and so his nationalism remained devout. While other Expressionists painted the decadence and squalor of modern Germany, he painted landscapes, seascapes, and religious allegories. He saw no conflict between Modernism and National Socialism. After all, what could be more German than German Expressionism?

“When National Socialism labelled me and my art ‘degenerate’ and ‘decadent’ I felt this to be a profound misunderstanding,” wrote Nolde, in an indignant letter to Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister for Information & Propaganda, in 1938. “My art is German, strong, austere and sincere.”

“I wasn’t put off doing this show because he was an enthusiastic Nazi, and I wasn’t put onto doing this show because he was an enthusiastic Nazi,” says Rainbird. “I think the work stands for itself in a lot of ways, but you can’t just walk round that, as people did for decades. They wanted to forget it.”

This ideological quandary may seem like ancient history, but its paradoxes are profoundly relevant to the artistic controversies of today. Nothing is more clear cut, you might think, than the story of modern art and the Third Reich. The Nazis were the baddies, the artists they persecuted were the goodies. Nolde’s story shows there were countless shades of grey. As Rainbird says, “It isn’t by any means as black and white as people say.” Even Nazi attitudes to modern art were far from uniform. Herman Goering hung confiscated works by banned artists like Franz Marc on his walls.

Today, our own society is wrestling with a comparable question – but sexual politics, not party politics, is the new battlefield. The big question for our times is: can you condemn someone’s sexual conduct, and still enjoy their art? If I watch a film produced by Harvey Weinstein, or a film starring Kevin Spacey, am I condoning their bad behaviour? Should Spacey really be erased from a movie, and replaced by another actor, as he was in the recent blockbuster, All the Money in the World?

Movie history is awash with brilliant films made by men with dark back stories. Tess and Chinatown are two of the greatest movies of the 1970s, and I’ve never seen a better film about the Holocaust than The Pianist. All three were made by Roman Polanski, a giant of the cinema, who pleaded guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor in 1977.

Woody Allen has committed no crime, but allegations of sexual abuse by Mia Farrow’s adoptive daughter Dylan (claims that Allen has always categorically denied) cast a shadow over his recent work, and has led to a number of stars, including Colin Firth, saying they won’t work with him again. Conversely, other stars, such as Alec Baldwin, have defended Allen.

“Actors, writers and producers are not cops, judges or jurors,” wrote the screenwriter Rafael Yglesias in Slate, explaining why he wrote a screenplay for Polanski. “In the work they choose to do, writers, actors, producers and directors can be accountable solely for its quality and its ideas.” The strapline to the article reads: “I was sexually molested as an eight-year-old, I wrote a movie for Polanski, and I choose to believe Dylan Farrow”.

Clearly, this is a debate with no easy answers. Love the sinner and hate the sin is the Christian doctrine. Blessed is the man (or woman) who sees both sides. Personally, for what it’s worth, that’s pretty much my position, too. I think art should stand alone, entirely separate from the morality (or immorality) of the men and women who make it. Caravaggio was a creative genius, one of the finest painters who ever lived. He was also a murderer. Should we remove his paintings from public galleries? Of course not, but maybe the passage of time makes us more sanguine. What if he was alive today?

“Fashions change – responses change,” says Rainbird. “Public institutions can be part of that change of view. They can lead, they can follow.” But whatever we decide is right today may not look right tomorrow.

The case of Oscar Wilde shows how attitudes to sexual behaviour have shifted. In 1895, when Wilde was sent to prison for gross indecency, whereupon his plays were shunned, the focus of public disgust was his homosexuality. The welfare of the young men with whom he had sex (rent boys, in modern parlance) was hardly touched upon. As members of the working class, they were considered unimportant by polite society. It was Wilde’s behaviour as a gentleman that was on trial.

Today, that moral standpoint is reversed. Thankfully, homosexuality is no longer a criminal offence, and Wilde’s sexuality is no longer condemned. It’s his treatment of those rent boys that seems unsavoury. Even if all of them were consenting adults, the disparity in age, status, and economic and social clout is far more troubling to the modern mind.

Back in 1992, I had my own brush with these dilemmas when I shook the hand that shook the hand of Adolf Hitler. I’d been assigned to interview the Fuhrer’s favourite filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl. The experience taught me it’s impossible to separate an artist from their art.

Unlike Nolde, Riefenstahl was never a member of the Nazi party. Her film of the 1936 Berlin Olympics is an undisputed masterpiece. Unfortunately, she also made Triumph of the Will, a powerful film of the 1934 Nuremburg Rally that still exerts a sickening yet seductive allure.

Leni was adept at defending her actions. She’d been invited by the German government to film a political rally, she said, attended by the head of state. The rally would have gone ahead without her. She’d added nothing. She simply went along and filmed what happened. It was purely a piece of reportage, a factual report of a historical event.

Her explanation makes perfect sense – until you see the movie. Unfortunately for Leni, she was incapable of filming a prosaic news report. Her genius as a filmmaker made the Nazis seem heroic. She made Hitler seem like a messiah. Her talent was her undoing, transforming propaganda into art.

This, it seems to me, was Nolde’s problem too. If he’d been just another journeyman, his membership of the Nazi party would be no big deal. Like Leni, he was far too talented for his own good. The thing that troubles us about him, and those moviemakers who’ve become today’s moral bogeymen, is that eternal gap between mortal man and his immortal art.

Emil Nolde – Colour is Life is at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin (www.nationalgallery.ie) until 10 June, and at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (www.nationalgalleries.org) from 14 July to 21 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments