Why Egypt is building a brand new mega capital city

Egypt’s new capital promises to be bigger, better, newer – and more vulgar – than any other supercity on the planet. But why does the country even need a futuristic megalopolis?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

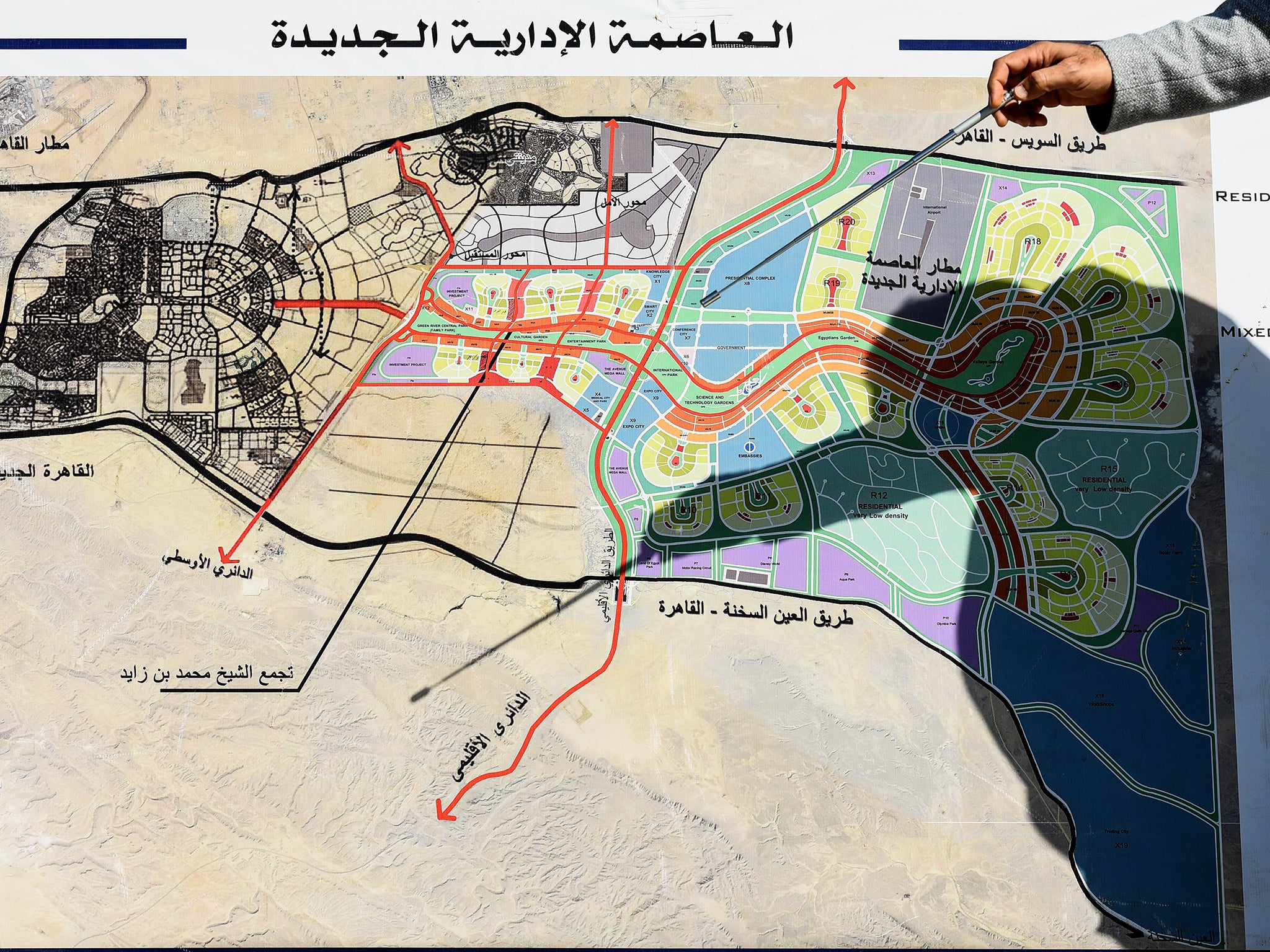

Your support makes all the difference.Cranes are hovering over a new town in Egypt – but this is no mere overspill like Stevenage or Crawley. The new administrative capital, or NAC (so new it doesn’t even have a proper name), is mooted to be the biggest planned city ever, aiming to house 6.5 million people and covering a 270 square metre footprint between the Nile river and the Suez Canal, east of Cairo.

It’s “let the desert bloom” redux. With Old Cairo’s circa 19 million population bursting at the seams, something needed to be done – and although it was only announced in 2015 at a conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, the futuristic megalopolis is happening apace, with off-plan flats already being snapped up, and new highways laid down.

But the NAC has bigger ambitions than real estate. By next June it aims to be Egypt’s new capital, rupturing Old Cairo’s thousand-year reign, with a new parliament, a central bank, an airport, a presidential palace (eight times bigger than the White House), a business district, Africa’s tallest tower, both Egypt’s tallest minaret and church steeple, and a theme park bigger than Disneyland. Stakeholders include the Egyptian army as well as Chinese and Emirati businesses: all to an original masterplan by US architects Skidmore, Owings and Merrill.

The NAC is the lovechild and legacy project of Egyptian strongman president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, and it follows in the (not-always noble) rollcall of capitals moving from older sites to new planned cities, from Brasilia to Abuja in Nigeria and Yangon to Naypyidaw in Myanmar.

And it offers a chance to rebrand Egypt as a stable and internationally inviting sort of place that is considering the future as well as being a guardian of the past. “We have the right to have a dream,” says Khaled al-Husseini, the mega-project’s spokesman, articulating a new mentality for the country following the turbulence since the 2011 Arab Spring.

The NAC also demonstrates that Egypt is leaving the Hosni Mubarak years behind (the fourth president of Egypt who ruled from 1981-2011), says Daniel Brook, the author of A History of Future Cities. “It shows that Sisi is a strongman: proposing a place where business gets done, perhaps in distinction to the Egypt of the past.” Some are even calling it Sisi-City.

What will the NAC look like? As Egypt expert David Butter of Chatham House says, the plans seem to have followed the examples of the UAE.

“It’s akin to Dubai, and the Al Massa Hotel has already opened in that spirit,” he says. “Apart from that it’s difficult to see any standout architectural theme.”

Although Egyptian architect Mai al-Ibrashy has called the NAC an opportunity to “create something that really turns its back to our identity”, it’s likely to follow an international style of curtain walls and geometric slabs with regional tweaks.

In his new book Egypt’s Desert Dreams: Development or Disaster? David Sims says that the main government district is said to be a mixture of “Pharaonic and Islamic architectural styles”, with street and neighbourhoods following curvilinear patterns rather than severe grids, nodding to a particularly Middle Eastern urbanism while offering a glossy surfeit of luxury housing.

Scepticism abounds, of course. But the NAC is an update of an older story: the new town as a medium for political and national grandstanding.

Many point to the need for new cities to be built to accommodate a world which the UN believes will have a population of 10 billion people by 2060. So there’s quite a boom of new cities at present, ranging from entrepots like Colombo Port City in Sri Lanka to education hubs like Kaust in Saudi Arabia and green icons like Sustainable City.

They include Tbilisi Sea New City in Georgia, Dumq in Oman and Forest City in Malaysia: itself aiming for 700,000 residents with highrises, malls and hotels on four artificial islands facing Singapore. Then there are innumerable cities in China, a feverish, fungi-like growth now helped by 3D printing, and this expertise is being exported.

Curiously, these new cities loop back to an earlier era of planned cities, the most famous of which is Chandigarh in India, Unesco-listed since 2016 and masterplanned by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier following partition in 1947.

Commissioned by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, it is now feted, but suffered brickbats as soon as it landed: that its sterile modernism, wide roads and roundabouts designed out India’s teeming street life and privileged cars over cyclists.

So keenly was this disparity felt that a study was carried out in the 1970s to assess whether its architecture accommodated or hindered Indian life – suggesting that the city was a western intervention that didn’t understand its locale.

This issue is facing another Corbusier classic, the National Museum of Western Art at Ueno in Tokyo. Like Chandigarh it was Unesco-listed in 2016 – the only world heritage site to be found in the greater Tokyo area – and is now subject to a “coals to Newcastle” argument that Corbusier himself was inspired by Japanese architecture and design.

It’s a long-standing argument: that the landing of capital, political ambition and foreign “starchitects” sometimes betrays the terroir. In Pakistan, the legacy of the 1947 partition led to the building of Islamabad, conceived in 1959 to unify the new country under a modern urban banner.

With tree-lined boulevards and residential sectors, Islamabad was largely designed by Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis (with government buildings by UK architect Robert Matthew Johnson-Marshall), whose grid system favoured the car with overpasses and intersections and again, it has been criticised for misunderstanding Pakistan and its social organisation.

Also under critical fire, and bridging the gap between these subcontinental statements and the NAC, is Astana. The Kazakh capital since 1997, it was planned by Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa and constitutes a showcase of baubles from a Norman Foster shopping centre, the Pyramid of Peace and the vast Accorda concert hall by Italian architect Manfredi Nicoletti.

No local architect could be found, and despite its gleaming vision of a glorious tomorrow, Astana has been criticised for harbouring a chilled street-level boringness in the middle of an inauspicious and windswept steppe.

Jonathan Aitken (yes, that one) wrote Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan referring to Astana (which means “capital”) as the ruler’s Versailles: and as if to express that sense of whimsy, the Bayterek Tower was built on a napkin drawing by the Nazarbayev. At the top, visitors can place their hands in a gold cast of the Navarbayev’s hand.

In a way, these gleaming planned cities exemplify the need for international kudos while fuelling grassroots tensions between the local and the global. The architectural concept of “critical regionalism” took hold in the 1980s, as a way to examine how a sense of place could be regained amid the growth of globalism. But as Brook says, there’s always an opportunity for fusion – even in China.

“The speed of construction there is astonishing,” he says. “But even now the Chinese are starting to want something that riffs on regionalism. They’re now making reference to past dynasties and at the higher end of the debate, trying to integrate aspects of China’s architectural history into these tall buildings.”

It’s also the reason why in the Gulf one finds “a certain degree of Arabian Nights and Scheherazade-style fantasy-making”, as Brook puts it, and there’ll surely a bit of that in the NAC.

And there is cause of optimism. Although Chandigarh’s concrete hasn’t aged well, it is now a heritage city that attracts tourists and whose manhole covers and chairs have been nicked to end up at auctions in the west, as if they were antiquities.

Might this be the fate of the NAC? It’s too early to tell, but David Sims isn’t optimistic, thinking that the “new capital is most likely to develop slowly into a sterile, half-filled government zone surrounded by mostly vacant stretches of stalled private developer projects, with the odd isolated success”.

All bets are currently on as to whether Sisi City will be the new Dubai or a case of “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments