The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Do animals dream of electric humans?

At the heart of the brain, beasts and homo sapiens may be more alike than either could imagine

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Many people who have owned a dog might suspect there is more going on in animals’ heads than commonly credited. However, one dog owner was responsible for what some see as the historical underestimation of animals’ inner experience: 17th century philosopher Rene Descartes, known for the phrase “I think therefore I am”, declared animals to be mere automata.

Emphasising differences or similarities between living things has important consequences for how they are treated. Philosophers such as Zygmunt Bauman and psychologists such as Professor Albert Bandura of Stanford University have documented how rationality and labelling can be used to disengage empathy and normalise violence towards people and nature.

Campaigners believe the welfare implications of how humans categorise non-humans will become starkly apparent as the fox-hunting season begins this week.

Jordi Casamitjana, head of policy and research at the League Against Cruel Sports, says: “Foxes, deer, hare and mink are not ‘quarry’ or ‘vermin’ as hunters normally call them. They are sentient beings with memories, emotions and experiences.”

Trail hunting: a cover for suffering

On 21 October, the National Trust’s governing board used several thousand of its discretionary votes to overrule a majority of members who voted in favour of a ban on trail hunting on trust land.

Trail hunting was introduced as an alternative after the ban on fox hunting imposed by the Hunting Act 2004. Casamitjana deplores the National Trust’s decision. “Large amounts of evidence show that those involved in trail hunting often chase and kill animals,” he says.

While the hunting fraternity are keen to emphasise kills are quick and humane, according to the League, autopsies reveal hunted foxes endure numerous bites and tears to their flanks and hindquarters – causing enormous suffering.

Casamitjana says: “If there is a lesson to learn about human-animal relationships in history it is that humans constantly underestimate not only the consciousness of animals, but also their capacity to suffer.”

Science’s underestimation of animal consciousness

The underestimation of animal consciousness from the Renaissance period resulted in the development of a scientific rule known as Morgan’s canon in the 19th century. Dominating the study of animal behaviour to the present, the rule states that scientists should avoid attributing motives and emotions to animals: animal behaviour should, it says, be explained in terms of simple mechanisms like instinct and conditioning.

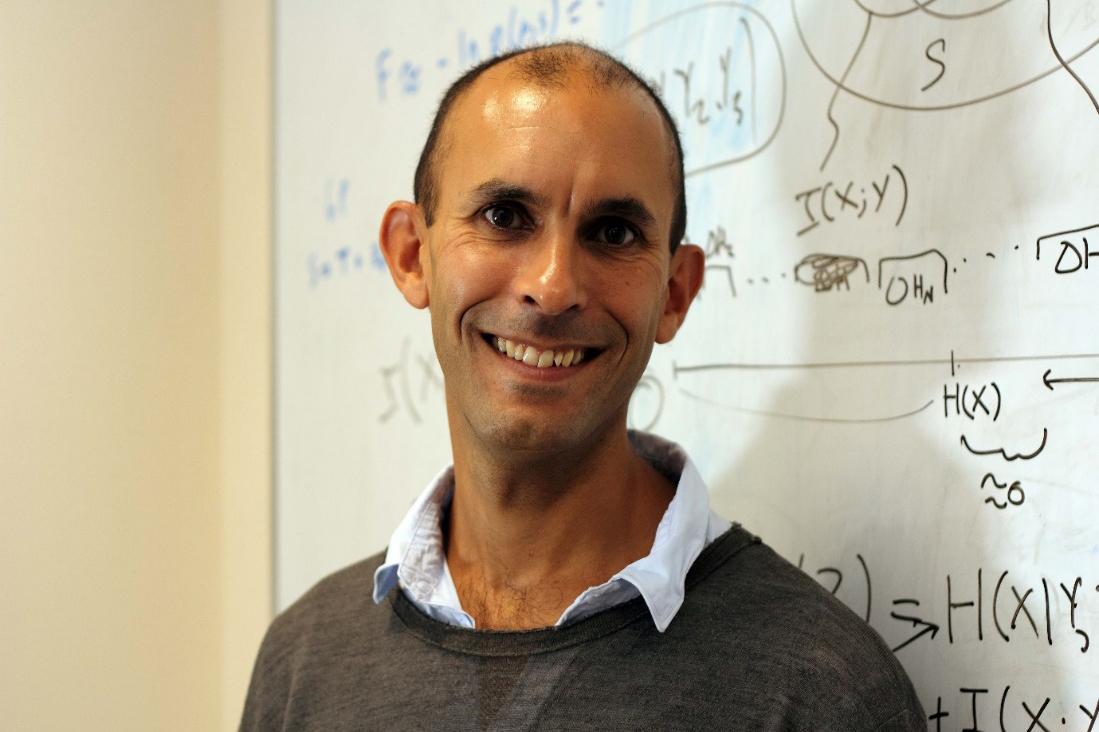

Anil Seth, professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience at the University of Sussex says: “I think Descartes was under a lot of pressure from the church to say that animals don’t have souls and they are just flesh and blood machines, whereas we have rational minds guiding our behaviour.

“I’m not sure he believed this. He had a dog called Mr Scratch, which I think is quite endearing. Mr Scratch went everywhere with Descartes.

“We now know that consciousness and self are not solely a matter of language, intelligence, reasoning and rationality – these things that we like to think of as distinctively human,” Seth adds.

Accumulating evidence of animal complexity

Despite the dictates of Morgan’s canon, from the mid-20th century, comparative psychology began to show that many species possessed previously unsuspected cognitive complexity. Some primates were found to fashion tools to retrieve food and crows were shown able to solve complex problems comprising several stages. Scientist Irene Pepperberg’s African grey parrot, Alex, was reported to possess the mental abilities of a five- or six-year-old child. Alex could sort objects according to abstract categories including size, shape and colour and independently invented his own zero-like concept.

Beyond problem-solving and intelligence however, animals were increasingly found to exhibit other capacities associated with human selfhood. Empathy has been demonstrated in species including rats. Dogs have been shown to possess a sophisticated understanding of human gestures and emotions. Frans de Waal, professor of psychology at Emory University in Atlanta even showed that capuchin monkeys possess a sense of fairness and strongly object to the unequal allocation of food rewards. Friederike Range at the University of Vienna demonstrated the same effect, called “inequity aversion”, in dogs.

Like humans, many animals have been shown to display individual variation in traits used to measure personality. Perhaps most impressively, chimpanzees, elephants, dolphins, and magpies have passed a test used to show the emergence of self-recognition in human infants. Magpies placed in front of a mirror with a mark on their plumage recognise their reflection, and will attempt furiously to remove the mark.

In 2011, Dr Tanya Broesch and others showed that some non-Western children unfamiliar with reflective surfaces had difficulty in passing the mirror test up to the age of six. Some have argued from this that the test is not sensitive enough and that many species of animals deemed to have failed it may be self-aware.

Convergence in the study of human and non-human consciousness

Despite growing evidence of self-awareness in animals and academic articles disputing Morgan’s canon, a shift in orthodox attitudes has only come following what is sometimes seen as harder, neuroscientific research into animal emotions.

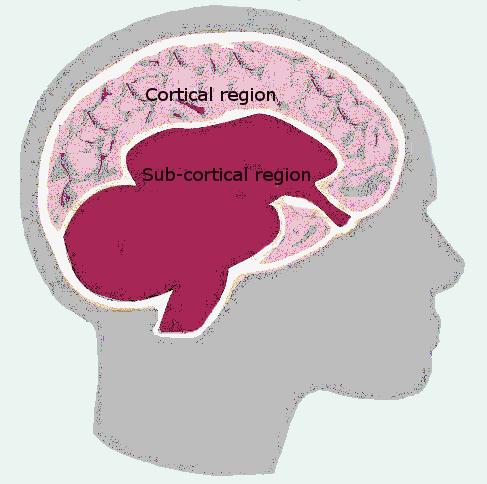

Seth has identified a “convergence” now occurring in our understanding of human and non-human selfhood. A series of discoveries have shown the importance of emotion to human consciousness and even to reason itself. At the same time, there is a parallel understanding that at the central, subcortical region; the very heart of the brain, many animals share with humans the same neurological structures for core emotions and selfhood.

Animal emotions: evidence from neuroscience

Professor Jaak Panksepp, of the Department of Integrative Physiology and Neuroscience at Washington State University, located the origin of self and consciousness in ancient subcortical structures at the centre of the brain.

Mapping regions responsible for primary emotions, he termed these areas: seeking, rage, lust, care, panic, play and fear. He found them to be similar across species, including humans. His findings about the play system in animals were aided by the discovery that when tickled, rats emitted high-pitched squeaks that were the equivalent of laughter. The animals clearly found this pleasurable and would chase his hand around the cage.

Panksepp argued these common brain functions showed that animals, like humans, have the neurological structures necessary for a core emotional self. He believes consciousness originally evolved to evaluate positive and negative emotions.

This research resulted in one of the most significant statements made about life on Earth: the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, written by Philip Low, edited by neuroscientists including Panksepp and witnessed by Stephen Hawking.

Humans, it says, are not alone in possessing the neurological structures necessary for conscious states. Many non-human animals have brain and mind functions at least comparable to human infants. “Evidence of near human-like levels of consciousness has been most dramatically observed in African grey parrots,” it reads.

I feel therefore I am

Converging with the discoveries about the emotional capacities of animals came research questioning the relative importance of reason and emotion in humans. Using functional MRI scanning, Chun Siong Soon and others reported in Nature Neuroscience that our conscious awareness of reaching a decision can occur up to ten seconds after the decision has been made subconsciously.

Not only can decision-making occur subconsciously, it has been found to depend on emotional processes. Feelings are often viewed as an obstacle to reason but in his paper, “The emotional dog and its rational tail”, Professor Jonathan Haidt of New York University showed that psychopaths who lack emotional intuition often fail cognitive tests of judgement. He argued that reasoning often appears after the fact to justify a decision that has already been made.

Antonio Damasio, professor of neuroscience, psychology and philosophy at the University of Southern California, argues that emotions are essential to animal and human selfhood because they fulfil the function of regulating life. He believes that even simple animals share primordial feelings that originate in the anciently evolved part of the brain.

The evidence of our own eyes

Under the dictates of Morgan’s Canon, any attempt to attribute inner life to non-humans has been routinely dismissed as anthropomorphism. A growing body of research now suggests, however, that to assume only humans have conscious emotional experience may simply be anthropocentrism – the tendency to view the world in terms of human existence.

Our intellectual achievements, culture and technological domination of the planet are often believed to mark a fundamental divide between humans and animals. Yet, if you ask most people what really matters to them, they may be more likely to cite the quality of their personal relationships and basic emotional happiness.

Images shared widely on social media appear to show animals displaying the same core emotions that many would consider fundamental to human experience.

In October, The Independent reported that video footage had emerged of a chimpanzee called Mama dying in Royal Burgers Zoo, Holland. Curled up and unresponsive, Mama suddenly appeared to smile widely, making loud cries of joy as she recognised, then embraced a professor she had known since 1972.

This behaviour is not restricted to primates. A film from the Facebook group, Best Video You Will Ever See, shows species as diverse as lions and geese overjoyed to be reunited with people they know.

These and other films suggest that animals are like us in the ways that matter most: they form attachments, love their young, play, enjoy affection – and can suffer.

Emphasising similarities rather than differences

Mimi Bekhechi, director of international programmes of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta) says: “We must break down the imagined barriers between humans and other species that lead us to mistreat animals.

“Like humans, animals are made of blood, flesh, and bone – and like us, they do not want to be caged and tormented or killed.”

She argued that just as we look back with horror at a time when we enslaved other humans because they were different from us, many of us now understand the idea that non-human animals are ours to use is equally as shameful and archaic. Before children learn to place species in the conceptual boxes of food or pet, they are often horrified at the idea of killing and consuming animals.

According to EU statistics, in 2014 in the UK alone, 971,276,000 poultry, 14,655,000 sheep, 10,465,000 pigs and 2,670,000 cattle were slaughtered – a total of more than 999 million animals.

Although not a vegetarian, Seth says: “It does worry me that, as with slavery, in a hundred years’ time we may look back and wonder what we thought we were doing, knowing what we did.”

He believes our current understanding of human and animal consciousness is sufficient to warrant at least a “precautionary principle” in our attitude to non-human consciousness: animals should be considered as potentially feeling, sentient beings. He says, however: “There is always this worrying disconnect between what we call discovery and how it affects our daily lives.”

Where to draw the line?

Fish

Many people feel that it is acceptable to eat fish (over other animals) believing them to be incapable of feeling pain, but it has been known for some time by neuroscientists that fish may be capable of primary consciousness. A 2014 paper said: “Fish appear to have the innate ability to experience negative states such as pain and stress in a way analogous to that experienced by other vertebrates.”

In March, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) argued that a new zebrafish study showed fish are: “sentient animals who form friendships, experience ‘positive emotions’ and have individual personalities.”

Octopuses

Octopuses possess a neurology so different to most creatures that some people have described them as aliens. Seth says that octopuses have a lot of neurons (nerve cells). Rather than being concentrated in a central brain, these are distributed throughout their tentacles.

He said that despite this radically different neurology, he had never encountered an animal that gave such a strong feeling of conscious presence. He says: “It’s very powerful. They take great interest in you and they’re not trying to please you. They’re pretty solitary animals.

“If there is anything like what it is to be an octopus, then it is so different to what it is like to be a human that it just emphasises the space of possible selves.”

In what may be an example of the disconnect between knowledge and daily conduct that he describes, Seth says he stopped eating octopus after this experience but still eats other animals.

Asked how he would sum up present understanding on animal selves and consciousness, Seth says: “There’s a big historical arc to all of this. Everyone thinks of the Renaissance as the source of all knowledge but in pre-Renaissance times people didn’t find it that contentious that non-humans had experience, had minds, had souls, whatever you want to call it.”

The National Farmers Union and the Master of Foxhounds Association declined to comment on the implications of recent neuroscientific insights for animal welfare.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments