The death penalty is a cruel, medieval practice – why won’t the US kill it off?

Support for capital punishment is diminishing among the American public, but Trump’s Supreme Court shows no sign of abolishing executions, writes Eric Lewis

The long, strange fever of the death penalty is starting to break with the American people. In 2018, 25 people were executed, down from a high of 98 in 1999.

The new governor of California, Gavin Newsom, placed a moratorium on executions, with the largest death row in the nation housing an astonishing 737 prisoners. Even conservatives have started to abandon the death penalty as wasteful and inefficient, requiring longer and more costly trials and decades-long post-conviction proceedings. Life in prison turns out to be a lot cheaper.

An occasional conservative channels his anxiety over government competence into concerns that the state can’t be trusted to get it right: rigorous studies show an innocence rate of those on death row of approximately four per cent.

The Pope has come out strongly against executions, leading some American Catholics to embrace abolition as church teaching on the culture of life. There seems to be an emerging consensus that the death penalty is an expensive, distasteful mess that has become a moral and penological anachronism. But the Supreme Court, buttressed with two new Trump appointees, is elaborating a death penalty jurisprudence that is as macabre as it is dishonest.

In recent years, the trend in execution methods has been towards the pseudo-medical lethal injection, presumably so that judicial consciences would not be pricked by accounts of the voided bowels of hanging victims or the fire coming out of the heads of inmates strapped to the electric chair. The inmate is instead strapped to a gurney and administered with paralytics and drugs that stop the heart, looking for all the world like a surgical patient receiving anaesthesia.

It hasn’t worked out that way, much to the chagrin of the current Supreme Court.

The participation of doctors is in violation of the Hippocratic Oath, so most executions are supervised by medical technicians. Faced with opposition by pharmaceutical companies to the misuse of their medicines in executions, states are experiencing a shortage of execution drugs, leading to states finding black markets, buying drugs from unreliable back room compounders and recklessly experimenting with various untried cocktails.

The result has been a series of executions devised and administered by amateur chemists and technicians that often make the hangman’s calculation of weight and drop length look scientific by comparison. The Death Penalty Information Centre describes 51 botched executions since the resumption of capital punishment in 1976, culminating with the execution of Clayton Lockett on 29 April 2014 in Oklahoma.

Despite prolonged litigation about the dangers of using an experimental drug protocol with the drug midazolam, Oklahoma scheduled Lockett’s execution while keeping secret the details about the drugs and their sourcing.

Ten minutes after the administration of the first drug, the sedative midazolam, the physician supervising the process (whose presence violated ethical standards) announced that the inmate was unconscious, and therefore ready for the other two drugs that would actually kill him. Those two drugs were known to cause excruciating pain if the recipient was conscious. Justice Elena Kagan stated at oral argument in subsequent proceedings that “potassium chloride, the third drug, is like being burnt alive”.

Lockett was not unconscious.

Three minutes after the latter two drugs were injected “he began breathing heavily, writhing on the gurney, clenching his teeth and straining to lift his head off the pillow”. Officials lowered the blinds to prohibit witnesses from seeing what was going on, and 15 minutes later the witnesses were ordered to leave the room. Lockett was heard crying out “this s*** is f***ing with my mind”, “something is wrong”, and “the drugs aren’t working”. Witnesses reported his last words were “my body is on fire”.

The execution was halted, but Lockett died 43 minutes after the execution began, of a heart attack, while still in the execution chamber.

After the Lockett debacle, Oklahoma changed its protocol, increasing the dosage of midazolam from 100mg to 500mg, not because there was data to show that dosage would work – there was none – but on the assumption that, if some people could be knocked out or killed at lower levels, the higher dosage surely had to make anyone unconscious.

There was a battle of the experts at the lower court as to whether the new dosage would keep the condemned prisoner unconscious throughout the process, given that midazolam had a ceiling effect so that it was not certain whether the higher dose would ensure continuing unconsciousness when the excruciating heart-stopping drugs were administered.

This Supreme Court applies an 18th century standard of what was appropriate punishment then; and declines to exercise the moral imagination to consider whether the fires of modern chemistry are analogous to those of the death pyres of old

Not surprisingly, the Oklahoma district judge found in favour of the state on the basis that the burden was on the condemned prisoner to show excruciating pain, not on the government to show its absence.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, Justice Alito wrote the majority opinion where he assigned the burden to the inmate to prove that it was intolerably cruel to be subject to a novel method of execution, despite there being no data to show that the condemned man would remain unconscious while he was given the drugs that Justices Kagan and Sotomayor said “may well be the chemical equivalent of burning at the stake”.

Then in a particularly cruel twist, the majority added a second requirement: if a defendant objected to a particular method of execution as unnecessarily painful, it was up to him to come up with some clearly better, less painful and available solution for his own execution. In the absence of the condemned prisoner coming up with a better deathtrap, some superior way for the state to kill them, then they will get whatever the state has concocted with what it has, even if it causes pain amounting to torture.

Justice Thomas concurred, but he would apply a more stringent standard: the method chosen can be excruciatingly painful as long as it was not imposing “super-added” pain, which imposed, on top of the pain associated with death, the infliction of additional terror, pain or disgrace for its own sake.

This concurrence, which appeared to allow anything short of gratuitous sadism, now appears to be the law of the land, as announced last month in Bucklew v Precythe.

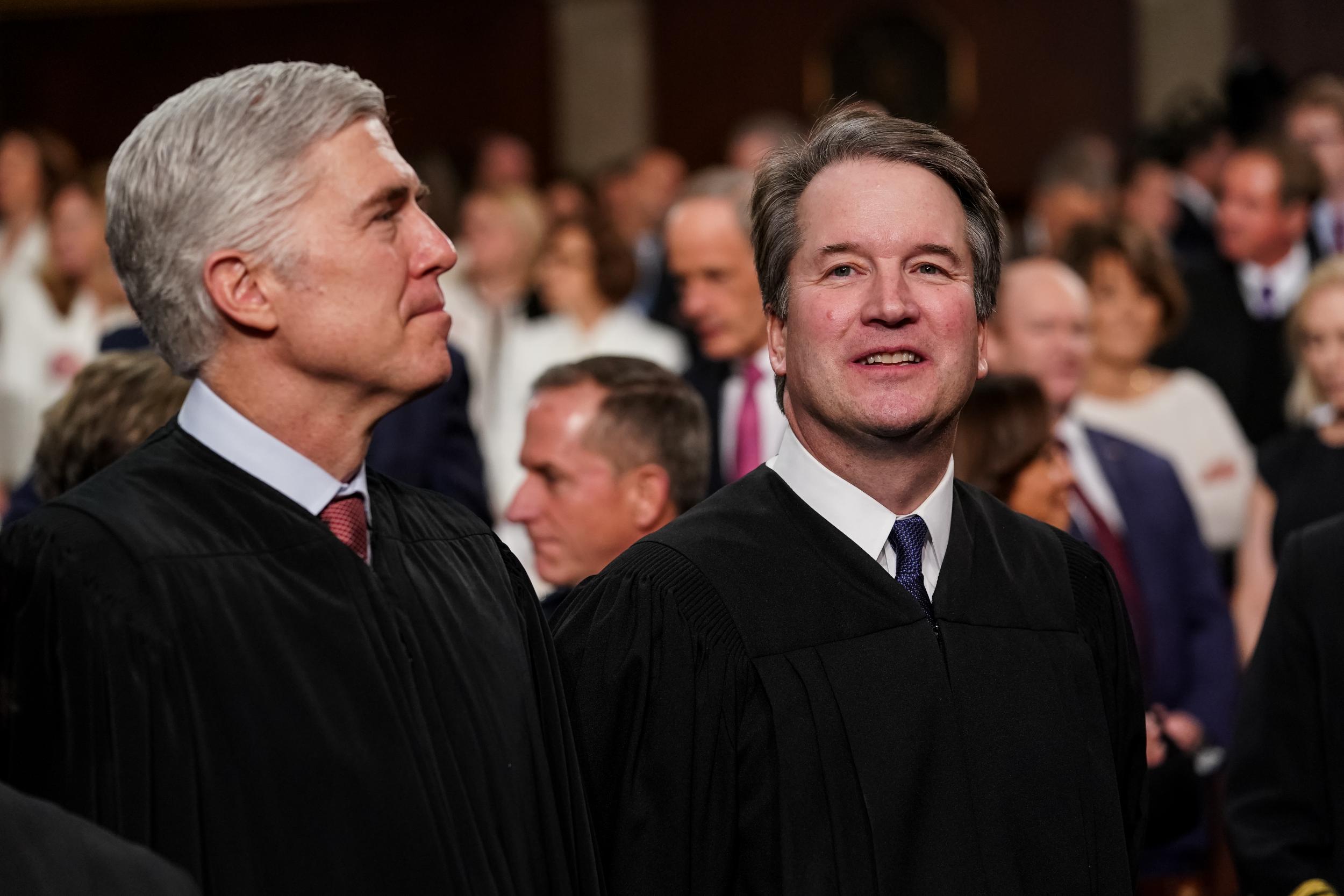

Bucklew was the first death penalty opinion for the court written by Neil Gorsuch, with newly confirmed Brett Kavanaugh providing the decisive fifth vote.

Bucklew, a prisoner on Missouri’s death row, claimed that Missouri’s lethal cocktail was cruel with respect to him because he had a rare and awful condition called cavernous hemangioma, which resulted in clusters of blood-filled tumours in his throat, neck and mouth, and he feared that the lethal injections would cause his tumours to burst, suffocating him slowly with the blood leaching from his tumours.

After first refusing to designate an alternative available method for him to be executed, Bucklew eventually stated that asphyxiation by nitrous oxide would be less likely to cause him to drown in his own blood and therefore would be his chosen preferable method.

In his ruling Justice Gorsuch made clear he has very little patience for death row inmates and their legal challenges. After irrelevantly summarising Bucklew’s grisly crime and the procedural history, Gorsuch introduces a bizarre and graphic history of capital punishment in America. He notes that the death penalty was contemplated at the time of the constitution and that the founders only excluded practices that had largely been found to be too gruesome to employ regularly and were no longer in frequent use.

He mentions “disembowelling, quartering, public dissection and burning alive”. These, he intuits, would have been seen as cruel to a mythical 18th century reader. He cites early commentary ruling out “the uses of the rack or the stake, or any of those horrid modes of torture devised by human ingenuity”.

Not for Justice Gorsuch punishments like “breaking on the wheel, flaying alive, rending asunder with horses ... maiming, mutilating and scourging to death”.

Having established his empathic bona fides, Gorsuch then notes that “the eighth amendment does not guarantee a prisoner a painless death – something that of course isn’t guaranteed to many people, including most victims of capital crimes”. True enough, but then the state is not the entity intentionally inflicting pain as a public act. He continues that the eighth amendment only prohibits pain which “intensified the sentence of death with a (cruel) super-addition of terror, pain or disgrace”.

Having rejected the “super-addition standard”, on the very next page, Gorsuch appears to allow even the gratuitously painful methods that he previously ruled out unless the defendant comes up with a better way for the state to kill them.

“Where (as here) the question in dispute is whether the state’s chosen method of execution cruelly super-adds pain to the death sentence, a prisoner must show a feasible and readily implemented alternative method of execution that would significantly reduce a substantial risk of severe pain and that the state has refused to adopt without a legitimate penological reason.” The clear import of this holding is that without the prisoner cooperating in his own execution, anything goes.

But Gorsuch shows, in his consideration of Bucklew’s request for asphyxiation, that in any case he has no serious intention of letting defendants choose their own method of death, rather than allowing the state a “one size fits all” approach to execution. He finds that nitrous oxide asphyxiation is not feasible or readily implemented because it has no “track record”, ignoring the fact that the court has upheld innumerable lethal injection protocols that have no track record.

And he disingenuously drops a footnote which makes clear that three states have authorised nitrogen hypoxia, but he lacks confidence that it has the performance history of, say, “the chemical equivalent of burning at the stake”.

Finally, he rules that Bucklew doesn’t get his requested gas because he hasn’t done enough homework on death row: “He has presented no evidence on essential questions like how nitrogen gas should be administered (using a gas chamber, a tent, a hood, a mask, or some other delivery device, in what concentration (pure nitrogen or some mixture of gases); how quickly and for how long it should be introduced or how the state might ensure the safety of the execution team.” The death row prisoner must not only choose an alternative method, but prepare the DIY manual as well.

The court has declared itself immune to pain, at least the pain of others

The decision makes clear that the “choose your method of execution” gambit is a cruel trick which the court has no real intention of implementing in the real world.

Gorsuch's opinion concludes with annoyance about all the time and effort that these pesky death row defendants take up. He notes that the state and victims have an interest in “timely enforcement” and they “deserve better”. He warns that the court would not countenance “an applicant’s attempt at manipulation”, and “courts should police carefully against attempts to use such challenges as tools to impose unjustified delay”.

How dare Russell Bucklew waste everyone’s time trying to establish, in vain, that he should not drown in his own blood? How dare Richard Glossip insist that care should be taken so that he is not “chemically burnt at the stake”?

This Supreme Court applies an 18th century standard of what was appropriate punishment then; and declines to exercise the moral imagination to consider whether the fires of modern chemistry are analogous to those of the death pyres of old.

This majority of this Supreme Court, one which may well be in place for many years, is committed to allowing as gruesome, painful executions as the states may choose. The spectacle may look more modern, but its effect is reliably medieval.

The court has declared itself immune to pain, at least the pain of others. Those who hoped that the death penalty would be relegated to a footnote in history, as it has been in law or in practice in 140 countries around the world, should not look to the federal courts either for abolition or for some show of empathy as to the method in which it is carried out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments