European retreat: Brexit shows we have learnt nothing from D-Day

Selective memories of wartime victories have fostered a fantasy of Britain and its place in the world today. Patrick Cockburn looks at how meticulous planning would have paid off in Brexit negotiations

Above all else, D-Day was a triumph of meticulous preparation by British naval commanders. Some 4,000 ships manoeuvred to land 156,000 soldiers together with their tanks, munitions and supplies in the right order and in the right places on a heavily defended coast. Crucial to winning the battle for Normandy was not only the initial landing but the ability to build up these forces at a faster pace than the German army was able to do.

Victory was won because the US and UK had more men and weapons than the enemy and they had foreseen and resolved many of the difficulties they would face once the invasion had begun. “In scope and thoroughness, in the complexity and scale of the problems solved, they [the royal navy plans] eclipse the renowned performance of the German General Staff from 1866 onwards,” writes Correlli Barnett in Engage the Enemy More Closely, his magnificent history of the royal navy in the Second World War. “They stand today as a never surpassed masterpiece of planning and staff work.”

The plan was drawn up by Admiral Bertram Ramsay, who organised the Dunkirk evacuation as well as the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942 and Sicily in 1943. Little known today, he was unquestionably the British air, sea or land commander with the greatest achievements to his name in the Second World War.

He was clear about his objective and warned against military and political decision makers who wanted “to have their cake and eat it”. (He was arguing against invading the south of France at the same time as Normandy). He stressed that the invasion was not an end in itself and insisted that the priority in planning should always be to maximise the army’s capacity to win the coming land battle in Normandy. He wrote: “The guiding rule must be the operational plan first, and the administrative plan later.” In other words, know from the beginning what victory would look like and only then devise the means by which it is to be won.

The commemoration of the 75th anniversary of D-Day will produce the usual bromides about Anglo-American achievements past and present. This will be accompanied by rhetoric from assorted national leaders gathered in Portsmouth today about the defence of freedom and democracy, a subtext being that it is threatened by populist nationalist leaders from Washington to Manila.

Celebration of military victories seldom prompt useful focus on the lessons of history (Gettysburg may be the exception that proves the rule). But it is worth looking at the British approach to D-Day on 6 June 1944 and compare it with another decisive moment in British history which comes when Britain leaves the EU on 31 October 2019. The first event saw the British military return to continental Europe after four years and the second will see its political withdrawal from the EU after almost half a century.

D-Day was an operation in a time of war and Brexit is happening in peacetime, but they have common features, most notably the extreme complexity of what was or is to be done and the vast importance to Britain of getting it done correctly. Complicated though the land battles in Normandy and the defeat of the German army on the Western Front turned out to be, the difficulties were not as great as those stemming from Brexit which will touch every aspect of national life.

Yet look at the different approach by Britain to these two critical events 75 years apart. In the case of D-Day everything was planned down to the last row boat with account taken of possible setbacks and unexpected developments. Compare this with Britain since the vote to leave the EU in 2016 with no idea of what a successful Brexit would look like in terms of relations with the EU and the rest of the world.

Little account was taken of the gross imbalance of power between Britain and the other 27 EU member states which, if they stayed united – as they did – were bound to dictate their own terms. This wilful ignorance was as if the British planners in 1944 had not bothered to count the number of German divisions in Normandy and the speed at which they could be reinforced.

D-Day was an operation in a time of war and Brexit is happening in peacetime, but they have common features, most notably the extreme complexity of what was or is to be done and the vast importance to Britain of getting it done correctly

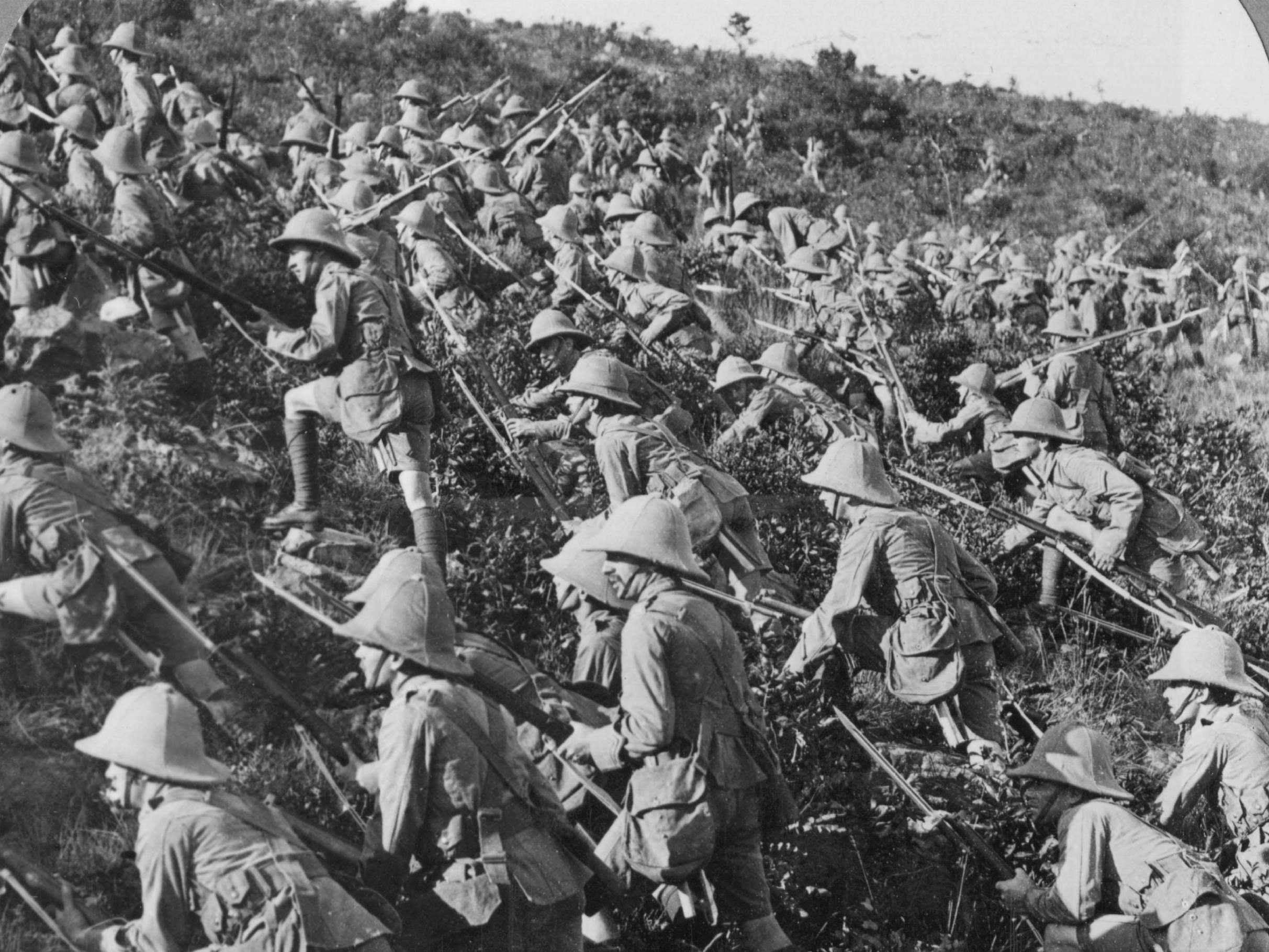

Britain’s departure from the EU is being conducted more in the spirit of Gallipoli in 1915 than the D-Day invasion. At Gallipoli, there was a fatal assumption that the opposition was weaker than it turned out to be and a belief that everything would be alright on the night. Much the same sort of wishful thinking has fuelled the Brexit process as slogans run up against facts.

At Gallipoli, the mood of hubris soon dissipated as troops were slaughtered on the beaches and in the rocky gullies but, when it comes to Brexit, the Eurosceptics self-confidence has been unaffected by repeated setbacks. Brexit more and more resembles a religious cult in which practical experience is discounted and explained away whenever it contradicts the tenets of the faith.

In fact, the British have slid backwards since D-Day in their ability to learn from the past. Admiral Ramsay and his planners had learned much about their strengths and weaknesses in landing on a hostile shore from the disasters of the Norwegian campaign of 1940 and the Dieppe raid in 1942. They benefited, moreover, from what they had learned from the successful Allied invasions of North Africa and Sicily.

A main reason why the Brexit crisis is proving so divisive and insoluble in Britain is that so little is learned from experience. Theresa May spent so long promising to deliver the undeliverable that her Withdrawal Agreement, though accurately reflecting the balance of forces between Britain and the EU, foundered because it was so far short of expectations which she herself had fostered. This failure clearly seems inexplicable to the millions who voted for the Brexit Party on 23 May and, presumably, for a no-deal Brexit. In so far as the frustration of Brexit is explicable to these voters, the failure must be the result of a culpable lack of patriotic determination. incompetence or betrayal.

Britain is either facing the gradual implosion of the whole Brexit project or a leap in the dark, just the sort of venture which Admiral Ramsay and his staff knew they must not risk if they wanted the Normandy landings to succeed.

Selective memories of wartime victories such as D-Day, without any real interest in how they were achieved, have helped foster a damaging fantasy picture of Britain and its place in the world today

The analogy between D-Day and Brexit-Day is useful because many of the ingredients producing success are the same in each instance: clear and realistic goals and the means to achieve them; knowledge of the terrain (military in 1944, political in 2019); correct assessment of the balance of forces inside.

It ought to be the Eurosceptics who draw the appropriate lessons from British history because it is they who claim to be drawing on its rich traditions. They have denounced Brussels and the members of the EU, notably France and Germany as rival nation states that have manipulated the EU in their interests and against those of Britain. Yet, while demonising other EU states as covertly hostile to Britain, the Eurosceptics are surprised and angry when these same countries do indeed seek to enhance their individual and collective interests at the expense of the UK.

A fundamental element of wishful and contradictory thinking by Eurosceptics about Brexit has become very visible. On the one hand, Brussels is portrayed as a great bureaucratic octopus with its tentacles strangling every aspect of British life. At the same time, the Eurosceptics argue and apparently believe that it should be easy enough to detach Britain from the clutches of this monster by simply departing without an agreement, unless we could get one to our liking.

There is a generalised detachment from reality here and it is fuelled by a distorted view of British history. It is a jibe that the British are fixated by their past achievements and that this is nothing more than nostalgia and myth-making to compensate for subsequent decline. There is a lot of truth in this, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, Britain was almost the only major state to escape defeat in war, civil war or occupation by a foreign power. No wonder the British feel nostalgic for such times.

But victory is notoriously a bad teacher because it leads to hubris and presumptions of unearned superiority. One of the many failings of the Brexit debate is how little reference there is to the real lessons of British history. One of the most obvious is that for 400 years Britain has depended on the royal navy for defence and continental alliances for successful offence. Spasms of British isolationism have been episodic, but the only time Britain has been truly without allies was during the American War of Independence in the 18th century, a short period before Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812, and the single year between the fall of France in 1940 and Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union the following year.

It is not likely to get a big mention during today’s celebrations, but D-Day would not have happened in 1944 if the bulk of the German army had not suffered decisive defeats fighting the Soviet Union on the eastern front.

Mythology about the Second World War would be harmless enough except that so many in Britain – including the political class – see the end of that war as the moment when history came to a full stop. People who know much about what happened between German-Italian forces and the British Army in Libya between 1940 and 1943 turn out to know nothing about the British role in the war Libya in 2011, the disastrous results of which are still with us.

The same is true of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. When the backstop and the Irish border became an issue in British politics because of Brexit, journalists living in Northern Ireland complained that incoming British reporters were astonishingly ignorant of the main features of the ferocious guerrilla war fought in Northern Ireland over 30 years before the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Only recently have the troubles of the Brexit era dented the idea in Britain that history – in the sense of events that transform lives for better or worse – is no longer something that happens to people in other countries. Selective memories of wartime victories such as D-Day, without any real interest in how they were achieved, have helped foster a damaging fantasy picture of Britain and its place in the world today. The potential result may be a sort of D-Day in reverse, with political and economic losses similar to a defeat suffered in war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments